RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

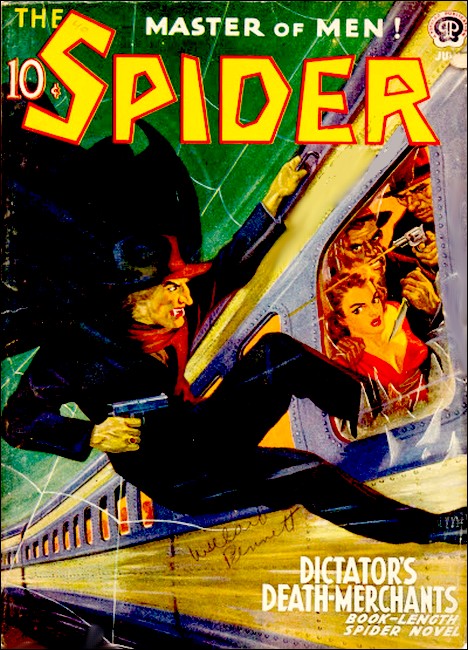

The Spider, July 1940, with "Murder Marches By"

To those terrified slum-dwellers, the weird sound of marching, invisible feet bespoke of countless, horrible European purges. Doc Turner, shrewd benefactor of the poor, looked for a material solution—even though he must virtually join the ranks of the Dead to find it!

A SOUND of marching thudded into Andrew Turner's ancient drugstore on Morris Street and it was not the pulse-stirring rhythm of a parade—drums and martial brasses—but merely the thud, thud, thud of many feet.

Working in his prescription room at the rear of the store, Doc's bony, acid-stained fingers tightened on mortar and pestle. His meager, age-stooped frame was taut. His head lifted, light shining in his white hair. His lips were hard-pressed beneath his bushy, white mustache. His old, faded blue eyes peered at the bottle-laden partition before him as though they could see through it and out through the store into the street whence came that thud, thud, thud of marching.

There was fear in this sound. There was inexplicable threat in this measured impact of hundreds marching through an appalled hush. There was in it a paralysis of panic that the old druggist had to throw off before he could make himself go out past the old-fashioned showcases to the door.

The sidewalk was crowded with white-faced slum dwellers. The hucksters stood motionless, staring out into the roadway that was roofed by the black-barred trestle of the "El." Unshaded bulbs cast pallid light over their pushcarts.

The sound of marching, slow-cadenced and terrible, came from that cobbled thoroughfare—yet the street was empty!

Empty of marchers—that is. A sedan was slewed in the middle of Morris Street; the hood of a truck jammed against its rear-end. There were other cars, other trucks, in the roadway, halted, their drivers blank-countenanced and goggling, but the thud, thud thud of marching tramped past them—seemed to tramp through them, for there were no visible marchers in Morris Street.

A rumble grew in the distant sky and became the racketing roar of a train overhead; it drowned out the tramp of the marchers. The thunder faded as the train slowed for the station three blocks away. It left a silence behind, a hush out of which the tramp of the phantom marchers was gone.

One must know the brawling, shrill clamor that fills Morris Street from dark to midnight; one must have listened to it, lived with it the many years that Doc Turner had, to feel that silence as he did, to know how much of terror the throbbing hush conveyed.

IT broke first in a vast hissing of exhaled breath. A shrill

voice rose out of the throng somewhere, "Madre de Dios!"

and a throaty one echoed that prayerful call with a hoarse,

"Bozhe moy!" Hands moved swiftly, making the Sign of the

Cross and a great-nosed old man in a long black coat droned a

prayer into his beard. Someone cursed in monotone. Someone

laughed hysterically, unendingly. The silence was swept from

Morris Street by a babble in all the languages of Europe.

"Mon Dieu!" A tiny woman, the black of her hair grey-threaded, her wrinkled face small-featured and Gallic, plucked at Turner's sleeve. "Qu'est—w'at was eet, Docteur? W'at was eet?"

The old druggist shook his head. "I don't know, Madame Legrange. I haven't the least idea."

"Eet was like—" In Madeleine Legrange's eyes, black and bird-like, was remembered horror. "Eet was jus' like zat night een nineteen fourteen w'en I leesten to ze Allemands, ze Boche, march outside een ze street. Jus' like zat zeir feet soun', tramp, tramp, tramp, all night, all ze night, marcheeng eento my belove' Belgie, an' w'en ze dawn ees grey in ze sky, zere begeen ze thondaire of ze beeg guns from Liège."

"Yair. Yair." Olive-tinted, sloe-eyed, the man who exclaimed from the knot forming around Doc. "From the slope of Masa Dagh I lizzen to de Turks march into Ras el Khanzir, an' dey sound like dat..."

"Und der Tsar's Soldaten, ven dey march into Kiev—" Rebecca Warnetsky, wrinkled like a walnut, nodded vigorously. "Oy! Mit deir swords und deir vips..."

Yes. It had been heard before by these aliens who lived in Morris Street, that sound of marching in the night. To us who are fortunate enough never to have known an oppressor, the tramp of cadenced feet means a parade. To them it meant invasion, enslavement.

"Look, folks," Doc Turner said. He must say something to them, something that would ease them. "It's foolish to let this thing upset you." It was for this reassurance that they were crowding around the wise old man who was their friend, their adviser in the strange ways of this strange land. For more years than he could recall he had taken care of them, and they had learned to come to him when frightened. "It did seem rather weird, but there's some simple explanation for it. It doesn't mean anything. You must not be afraid."

Was he certain? Was he quite certain? There was a sound of marching in the world tonight, tramp of marching and thunder of gunfire. In Finland people had gone to sleep in peace and waked to hear alien invaders tramping into their peaceful countryside, without reason, without warning. In Norway—this was absurdity! Things like that might happen there across the sea, but here—never!

"Hey, Doc!" A burly youth in mechanic's overalls, his thatch of unruly hair carrot-colored, shouldered in through the crowd. "Doc!" he gasped. "You better 'phone for a couple ambulances in a hurry!"

"Ambulances, Jack!" The young man was Jack Ransom, Doc Turner's companion, his good right fist in his battles against the criminals, mean and dangerous, who prey on the helpless poor. "What's happened?"

"Plenty." Unaccustomed grimness hardened Ransom's usually kind countenance, so that the freckles dusting the bridge of his nose, and the smear of auto grease on one cheek, had no element of humor. "Four—"

"Open up there!" a hoarse command came from behind him. "Open up." The knot of humans split. A policeman filled the aisle opened to the drugstore's door. A limp form lay across his arms, the body of a small boy.

THE boy was only the first who was carried into Turner's

Pharmacy. When the ambulances arrived, their interns had three

others to examine: Anatolas Xarchus, who had cried his 'epples'

and 'strumberrehs' on Morris Street as long as anyone could

recall; Hyam Ginsberg, shamus of the Hogbund Lane

Synagogue; and Rosita Manucci, mother of ten

bambini.

Each had been knifed in the back. Each had been leaning on a pushcart, or against an "El" pillar, or in some other manner had been supporting themselves, so that they had not fallen when the steel entered their flesh. Each was dead.

As far as the police could discover, there was no possible connection between them. Doc Turner could have told them that. He knew the affairs of these people better almost than they themselves.

He knew that the four had no enemies. He knew that no one could gain by their death. He knew that it was only by blind fate that they had been chosen to die.

"Just because they were standing in a way that they would not fall when they were stabbed," he told Jack Ransom when the store had at last been cleared of bodies and interns and police. "And because no one was near enough to see the killer stab them, although there was very little chance of anyone's seeing anything, looking as we all were for the phantoms that seemed to be marching out there."

"Seemed to be?" Jack straightened a bottle of perfumed witch hazel on the scratched glass top of the showcase by which they were standing. "Do you mean that was a fake?"

"Of course. It was deliberately done to concentrate the attention of everyone in the crowded street, so that those four murders could be perpetrated under the very noses of hundreds."

"Deliberately! How, in the name of everything holy—"

"I don't know." Doc's face was bleak, almost expressionless. "I don't know, son, but I intend to find out."

"And why?"

"That too, Jack," the old druggist murmured, "I intend to discover." The look in his eyes was one Ransom had seen there many times before, and each time he'd seen it there someone had gone to prison—or had found his career of crime ended in a more permanent and effectual manner. "How, and why, and by whom."

"Let's go!" Ransom burst out. "What are we waiting for?"

"For the killers to show their hands." Doc's own hands spread wide. "Morris Street, the whole neighborhood, has been combed by fifty detectives and they've found out nothing. What is more to the point, I have been told nothing that sheds any light on the mystery, and you know that these people would tell me without asking things they would refuse to tell the police. It's going to be hard to wait, Jack, but we'll have to do that until those who are behind this thing make their next move—and make the inevitable mistake that will deliver them into our power."

THE police evidently had the same idea, for all that night and

all the next day, Morris Street and the tenement-lined, narrow

streets that lead off from it saw strangers wandering aimlessly

about, strangers with hard jaws and heavy fists and the

peculiarly blank faces of professional dicks. And night sifted

down again through the barred network of the "El" trestle, and

the lights over the pushcarts came on, and Morris Street's

cracked sidewalks were thronged as usual.

Not quite as usual. Four to the block, policemen stood, blue-uniformed guardians about which the slow-moving human current swirled, and there was apprehension on the faces in that stream.

A MUSCLE twitched in Jack Ransom's cheek as he stood in the

doorway of the drugstore. "They're afraid, too, Doc. They're

scared as hell."

The old pharmacist, beside him, nodded gravely. "Yes, my boy. You can almost feel the miasma of fear that flows out there, between these rain-stained tenement facades. You can almost reach out and feel it flow between your fingers."

Jack's feet shifted, uneasily. "You know, Doc, I've got a queer hunch that something's going to happen at nine o'clock."

"At nine o'clock? Why precisely then?"

"Because I happened to be timing a motor test-run in the garage last night and was looking at the clock when that sound of marching started. It was exactly nine—"

He broke off. Somewhere in the blackness above the "El" trestle a tower-clock was striking. Bong. "Listen," Jack whispered. "When that clock stops striking, it will be nine o'clock."

Against all reason Doc Turner was listening to those slow, welling strokes as they tolled doom, counting them. Six, seven, eight. Bonnng, the ninth brazen clang struck the night and hummed, fading....

Thud! Feet pounded in the traffic-filled space between the tall "El" pillars. Thud! A hundred feet thudding at once on the cobbles and lifting, and thudding down again, in mechanical unison.

The parade of the phantoms had begun again, out there in Morris Street.

Brakes screeched. A woman screamed, high and loud and shrill. The police were half-crouched, guns out, eyes wary. Thud, thud, thud. In doorways, at street corners, rock-jawed, blank-faced men in plain clothes had revolvers out too, and their lids were narrowed, their muscles taut for instant action.

"Look, Jack," Doc pointed them out. "Our friends won't have much chance to do their killing unobserved tonight. The people may be staring out into the street, but those boys aren't."

Hands fluttered, brow to breast, right shoulder to left. The unseen hosts tramped out the vintage of terror. A bearded Hebrew ancient muttered a prayer into his beard. Thud, thud, thud. A mother gathered her brood in her arms, breath squealed from a peddler's constricted throat. So near, so distinct, was that tramp of a long column out there it was incredible that one could not see them.

In the distant sky a rumble began, the sound of an approaching train. "Ahhh," Doc sighed. "It's over—" Light exploded in Morris Street, white light blinding as the sun. White light burning out sight! Overhead, thunder crashed. The racket of the "El" train died away and the white, terrible brilliance was gone, succeeded by the blackness of sight-nerves paralyzed.

The sound of the marchers had ended.

Sight returned slowly to Doc. He saw his people, rigid in terror. He saw the policemen, the detectives, pulling left hands across dazzled eyes. On the sidewalk he saw three bodies lie crumpled. Beside each was a spreading scarlet pool.

"They've done it again," he whispered through frozen lips. "They've done their killing while the police were blinded with a gigantic magnesium flare." And then the panic broke in Morris Street, the howling, the rush of the terrified mob, the crash of overturned pushcarts, the agonized screams of women and children who had fallen and were being trampled...

THE third night there were ten policemen to the block, and

five detectives, and all wore dark goggles. Ten policemen and

five detectives on each block of Morris Street—and hardly

anyone else. The pushcarts remained in their cellar garages,

fruits and vegetables rotting. The laborers in their toil-worn

clothing, the shawled housewives, the yelling children, shunned

Morris Street. The storekeepers waited in their empty shops for

customers that did not come.

And there was no sound of marching, no tramp of phantom feet on Morris Street that night.

In the back-room of Turner's drugstore its owner swiveled his chair to a battered old roll-top desk and started fumbling in the sea of papers that cluttered its surface. "I think they made the mistake I've been hoping for," he murmured. "I think perhaps they have."

"Cripes, Doc!" Jack Ransom grunted from his perch on the white-scrubbed dispensing counter. "How could they have made a mistake when they haven't done anything?"

"That's what I mean, son." The old druggist unearthed a letter, glanced at it. "That's exactly what I mean. They haven't done anything tonight, and—here." He held the paper out to the youth. "This came today."

Jack took it, looked at it disconsolately. The heading was ornately lithographed:

Telephone: Morris 4-6572

MARTIN AND MERTON

Store Brokers

72 Pleasant Ave., City

Mr. Andrew Turner

Morris Street and Hogbund Lane

City

Dear Sir:

We have had an inquiry concerning your store. If you would be interested in disposing of your lease and good-will, for cash, our client is prepared to close the deal at once. Please telephone or write us if this would appeal to you.

Very truly yours,

Martin and Merton

"So what?" Ransom yawned. "They've typed in your name and address, but the rest is obviously a mimeographed form. All they want is to get a listing. You've certainly gotten plenty of these things before."

"Yes, I have. Except for one thing. Prospective purchasers for a drugstore of this kind, an old-fashioned pharmacy in a poor neighborhood, have little or no money. They expect to pay a small amount down, give a mortgage for the rest of the price and pay it out of income."

"I still don't see—"

"Listen to me, then. I'll explain." They talked for a long time, those two, and when they'd finished, excitement burned in Jack Ransom's eyes.

THE morning sun bathed the red brick front of Number Seventy-two

Pleasant Avenue. It was a four story building with a small

manufacturing enterprise on the ground floor, as indicated by the

black-painted store windows and small offices above. In the tiny

lobby Doc Turner found a directory that told him Martin and

Merton held forth in Room 2.

The stairs were narrow, creaking. The corridor on the second floor had dirty plaster walls, doors from which the paint had long ago peeled, but the tin sign on the door that was number "2" was new.

Curiously enough, after the old druggist had ascertained this, he went to the very end of the passage, raised the grime-crusted window there and looked out before he returned to Room 2 and entered a small office filled with sunlight.

The usual flimsy railing ran across the room, two steps from the entrance. The wall to Doc's left was taken up almost entirely by a none-too-clean window, against that to his right stood two green metal filing cabinets. Directly ahead was a flat-topped, oak desk betraying hard usage.

The man who sat behind the desk was in his shirtsleeves. His face was flabby. His pale eyes, pouched in bluish, dissipated skin-bags, seemed a little surprised as they lifted to his early visitor.

Doc took his hat off, stood at the railing, a shabby, frail-seeming, almost pathetic little figure. "Good morning," he offered, tentatively. "Mr—er..."

"Merton," the other growled. "Alonzo Merton. And who the hell are you?"

"Andrew Turner, Mr. Merton. The druggist from—"

"Morris Street. Sure. Sure, I know." Merton was suddenly genial. "Come in here. Just tickle that door-jigger under the rail of the gate and come in and pull up a chair." And when Doc had complied, he went on, "You didn't have to bother coming here in answer to our letter. All you had to do was phone or write and me or my partner would have come right over."

"Well," the druggist shrugged. "I had a relief clerk coming in today anyway. You—you wrote that you had a buyer for my store?"

"And how! With spot cash, too. A thousand bucks down, and you can take your hat and walk out, a free man at last."

"A thousand!" Turner fumbled with the brim of his hat, blinked. "But—but my stock alone is worth more than that."

"Our client don't want it. You can move it to another location, sell it. He's going to remodel, put in all fresh goods. All he wants is your agreement not to reopen within ten blocks of that location, and an assignment of your lease."

"My lease has eight years to run. Isn't that worth—"

"We know all about your lease. We looked it up in the Register's Office. It's worth exactly a thousand dollars to our buyer, and not a cent more. Look." Merton selected one from a sheaf of legal-appearing documents on his desk, jerked it out and slid it across to the pharmacist, with a fountain pen. "Here's the assignment, made out to me as agent, and here," his hand came out of his pocket with a huge roll of bills, dexterously stripped two from it with thumb and forefinger and returned the rest. "Here is the thousand, in two five centuries. Sign that and you get this, net. The buyer pays my commission. Take it or leave it."

DOC tugged at his mustache, ran a finger inside his collar. He

was palpably confused, almost intimidated, by Merton's urgency,

his overbearing manner. "I—" he licked his lips.

"I—isn't this rather a peculiar manner to handle a

transaction like this? After all, you—the man who's

buying—hasn't seen my store. He doesn't know the kind of

trade I have, he doesn't know how much I take in, or—"

"Maybe you don't want him to come to Morris Street. Maybe you don't want him to know what's going on there." Merton winked. "Is he offering enough for what you have to sell him or not, that's all that concerns you. And—"

"No." The old man straightened in his chair, his voice took on a firmer tone. "That isn't all that concerns me, Mr. Merton, not by a long sight. I—I'm not just selling a lease and four walls. I'm turning people over to my successor, poor, bewildered people whom I've served many years. Good-will, you called it in your letter, and good-will it is—not theirs for me but mine for them. I must know to what kind of man I'm turning them over. I must know if he'll be honest and capable and fair to them, or if he intends to exploit them and defraud them, as so easily can be done in my profession. I must meet this man, or I do not sell."

"I'll be—" Merton's face had grown purpler by degrees all through this incomprehensible speech. "I—" He stopped, started again. "I'm sorry. My client does not wish to appear in this transaction until it is completed."

"Then I shall not sell." Doc rose. "I cannot." He started away, reaching blindly for the catch in the railing gate.

"Wait!" Merton took hold of his desk-edge with both hands. "Wait, Mr. Turner. Listen to me. I didn't expect to have to tell you this, but I'm the real buyer."

Turner came about at this, peered at the flabby, shirt-sleeved man. "You—but—you're not a druggist."

"No." Alonzo Merton didn't seem too happy at the admission. "No. And I don't intend to run a drugstore there."

"No drugstore!" Doc was flabbergasted. "You—"

"I'll tell you what else. I won't be ready to use that place for maybe a year, or maybe more. You assign your lease to me and you can stay there till I'm ready. The only difference will be that you'll pay me rent instead of your present landlord, and you'll have this thousand dollars to play with."

"No." The druggist shook his head. "No. I don't know what you're up to, but I don't like it." He pulled the gate open, went through it, took hold of the knob of the door beyond. "Good day, Mr. Merton." The knob turned in his hand—but the door did not open!

Merton came to his feet, a burly man almost a head taller than Doc Turner, twice as wide.

"You—something is the matter with this door," Doc faltered. "It won't—"

"Nothing's the matter with it," the big man said, lumbering through the gate in the railing. "I locked it, by pressing a button under the edge of my desk." A smile licked his thick lips and it was the smile of a cat that has its mouse cornered. "You had me fooled for a little while, but I tumbled to you in time. You came here to find out something and you got it out of me, but you won't get out of here with what you've learned." He loomed over the old druggist and there was infinite menace in his bulk. "You were too smart, Andrew Turner, for your own good."

"Ahhh." Doc sloughed off his pretense of confusion, at weakness. "I was afraid you were not as slow-witted as I hoped, as soon as I heard you say that you had inspected my lease in the Register's office. I knew then, that you'd found out it was an old form, that it did not have the usual clause terminating it in case of condemnation proceedings by the city or state."

"Right on the head, mister." Merton grinned as one who could afford to grin, holding all the trump cards.

"You plan to buy up all the houses along Morris Street very cheaply, don't you? But you discovered that the stores on my particular block all have those old leases, so you had to clear those up. So you started out to ruin their business by terror, by murder, driving away all our trade. You sent out these letters at the psychological moment, figuring that the storekeepers would rush to sell before a possible buyer heard of what was happening. That's it, isn't it?"

"Sure. So what?"

"You wouldn't mind telling me what is shortly going to make property along Morris Street so valuable, would you? Just to satisfy an old man's curiosity?"

"Seeing as you're not going to have a chance to tell anybody else, I might as well. A new housing project's going to be put through in that section. Everything's going to be bought by the city and torn down, and what's going to be paid for land and leases and all is nobody's business."

"Ah yes. And somehow you got wind of it and are planning to cash in. One more question. That sound of marching—how was it produced?"

"Nix. I wouldn't tell that to my own mother."

"You'd kill your own mother for ten cents. But you don't have to tell me. I'm quite sure I know."

"You do, huh?"

"Yes. Look here." Doc's hand slid under the flap of his coat. "I—"

"Hold it!" An automatic snouted at him suddenly, from Merton's fist. "I'll put lead—"

"Oh, good Lord, Mr. Merton," Turner chuckled. "I'm too peaceful to carry a weapon, especially in a shoulder holster. If you don't believe me—suppose you reach into my pocket yourself and take out my wallet. I simply wanted to show you a clipping from the New York Herald-Tribune of July 17, 1938, that told me how you produced the sound of the phantom marchers."

"From the Herald—"

"Yes. I make a habit of keeping items concerning odd applications of scientific devices. Of course, if you're not interested—"

"Go on," Merton grunted, pulling out the frayed leather folder the druggist wanted and handing it to him. "Have your fun." The big man's nonchalance covered his eager curiosity. "What about that clipping?"

"Here it is." Doc brought out the tattered scrap of newspaper, held it for the other to read. The headlines told the whole story:

FRANCE DEVISES A 'SOUND CAMOUFLAGE'

IDEA IS TO CATCH ENEMY OFF GUARD BY CREATING NOISE OF A FAKE ATTACK

LOUDSPEAKERS WOULD SEND SOUNDS OF TROOPS AND PLANES ACROSS FRONT

"That's what you did," the pharmacist commented, folding the clipping and buckling it carefully into his ancient wallet. "You made, or bought, a record of marching men, constructed a portable unit containing an electric phonograph, an amplifier and a loud speaker. You, or your accomplice, got on the rear of an 'El' train with this unit, dropped off its rear as it slowed for the Morris Street Station, tapped in on the third rail and started the record. The killer, down in the street, had exactly five minutes to do his stabbing before the next train, the one that passes overhead at nine-four, would come along. As soon as the operator of the loud speaker unit heard the next train, he'd disconnect and hop on its rear platform.

"Few people realize that those trains run on as strict a schedule as the transcontinental railroads, but this circumstance enabled you and your confederates to synchronize your murderous activities without a chance of error. The second time you dropped a magnesium flare to blind the pol—"

The wallet flipped from Doc's hand into Merton's face, and the druggist dropped under the red jet of the fire that streaked from the big man's gun. The automatic dropped to the floor. Merton was pawing at his face, blithering in a queer agony, his eyes blinded by powdered capsicum, his throat constricted with ground ammonia, but Doc had darted through the railing gate, was dashing for the desk to release the door-lock.

He reached it, found the button and jabbed it, and started back for the now unlocked door. Froze, as a new voice said, through Alonzo Merton's blabberings, "Get 'em up high, or I'll let you have it right here."

Doc halted, reached for the ceiling. He twisted to that command, saw that the green filing cases were swinging out on a pivot. Through the aperture revealed in the wall a tall, emaciated individual stepped, a keen, wicked knife balanced on the palm of his hand as only a skilled thrower holds his blade.

"The senior partner, I believe," the old pharmacist said calmly. "Martin—or Martini perhaps. The killer, of course. I see the cord that enabled you to retrieve your knife after you'd hurled it into your victims' backs without coming too near them. That was a refinement I hadn't thought of."

"All right, wise guy," the black-haired Martin sneered. "You've got everything figured out the way we worked it, but it ain't doing you no good. You're turned the way I want you now, so I can get you in the gullet, and—"

"Guess again." The hall door smashed open and men led by Jack Ransom poured into the room—hard-jawed men with guns.

The detectives were manacling the murder-firm of Martin and Merton, but Jack had his arm around Doc Turner's shoulder and was babbling happily. "You worked it, Doc! You worked it swell. We came up the fire-escape down at the end of the hall and got a dictograph recording of your talk. We've got everything. But believe me, my heart was in my mouth when I heard that buzzard say he'd locked the door, and I thought we couldn't get in in time to save you when the fireworks started."

"Mine was rather choking me too, son," Doc Turner smiled wearily, "at that particular instant. I had visions of revisiting Morris Street only as a phantom, marching down the street, thud, thud, thud, invisible to all my friends."

"It's your friends that would make the big parade, Doc, all the people who love you. If they started marching down Morris Street they'd make a line four abreast from here to there. But they wouldn't be ghosts, thanks to you."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.