RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

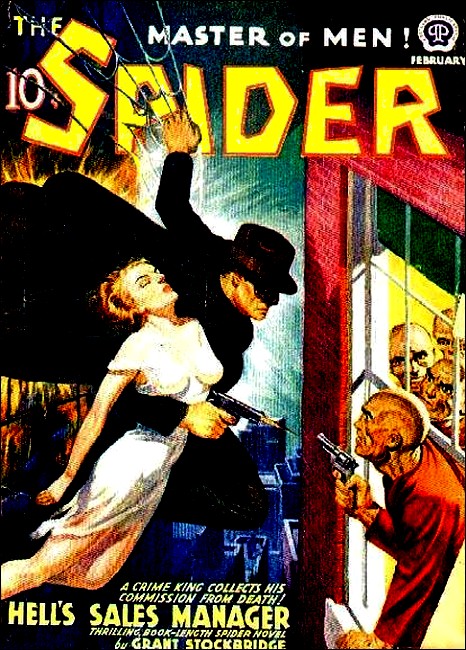

The Spider, February 1940, with "Death's Dancing School"

When little Jimmy Orling told Doc Turner his sister's secret—that she would soon be rich—Doc suspected a plot against the fairest maidens of the slums... Two lead-blasted young bodies told Doc, tragically, that he was right!

DOWN where the elevated tracks roof Morris Street, electric bulbs high-hung over the pushcarts were like individual small suns, each glaring down on its own tiny hillside farm. Here a miniature slope of scarlet peppers, dark green cress, and creamy gourds bulging with pungent cheese was tended by a swarthy Sicilian. Next in line, a sloe-eyed Armenian hawked frothy laces and vivid-hued Oriental rugs. Further along the thronged sidewalks of the slum thoroughfare, shawled Galician crones knowingly pinched the produce offered by a curly haired Greek from the Peloponnesus. At the curb in front of Andrew Turner's corner drugstore a round-faced Slav haggled with a bearded Hebrew patriarch over a pair of sleazy suspenders.

Hucksters raucously cried their wares, tattered gamins screamed in raucous play, trucks honked for passage. This was a typical Morris Street Saturday night.

From the doorway of his ancient pharmacy, Doc Turner's faded blue eyes, in which there was more than a hint of worry, surveyed the familiar scene. The little, white-haired old man seemed to be sniffing, through the heavy odors of over-ripe fruit, some evasive but sinister scent.

Like that which warns a veteran shepherd-dog of the wolf-pack gathering in distant hills, some obscure instinct presaged to the aged pharmacist a new menace threatening these people he had long protected from those meanest of criminals—the wily ones who prey on the very poor.

A tow-headed urchin pushed through the shifting throng, eagerly offering paper shopping bags for two cents each. "Hello, Jimmie," Turner called to him. "How's business?"

The ten year-old stopped, hitched up trousers which immediately sagged on to dirt-smeared, bare shins. "Pretty good, Doc," he grinned. "I took in twenty-four cents already tonight."

"That's grand," the druggist applauded. "You keep that up and you'll be a rich man when you grow up."

"Aw, shucks. We're gonna be rich long before I grow up." Jimmy Orling's scrawny shoulders straightened. "You just wait till Sue—cripes," he interrupted himself. "I'm not supposed to say nothin'—Well, I got to be hustlin' along." He turned away.

Doc grasped a pipe-stem arm. "Jimmie," the old man asked, low-toned. "What were you going to say? What's the big secret about what's going to make you and your sister rich?"

The freckled small face was abruptly mask-like, the frank grey eyes suddenly veiled. "Nothin', Doc. I was just shootin' off my mouth."

"Jimmie!" He was squirming, tugging to get away. "Where has Sue been the last four or five days? I haven't seen her around."

"Gee, Doc! I can't—cripes! There she is now." The girl running out of Hogbund Lane, past the drugstore window's corner-post, was slight, blonde-haired, winsome. "Sue!" Jimmie yelled. She stopped short, her hand going to her mouth as the youngster broke loose, bolted toward her. "Susy!" She was white-faced, her eyes big with terror. Jimmie reached her—and then it happened.

OUT of the side street from which Sue Orling had appeared came

a stuttering rattle, like that a dozen boys might make running

sticks along a picket fence. Jimmie thudded halfway across the

street. His sister crumpled in her tracks, as a passing youth

collapsed beside her. The chatter ceased, was replaced by the

roar of a suddenly accelerating car motor.

The sprawled bodies were staining with scarlet as Doc Turner darted past them. Someone screamed, shrilly. A hundred feet down the dim-lit gut of Hogbund Lane, a black sedan was just completing a U-turn. In the instant Doc glimpsed it, it straightened and sped east, its tail-light blinking above a mud-spattered license plate. Footfalls thudded behind the old druggist; voices shouted gutturally. The murder car reached the end of the block, whipped around the corner into Pleasant Avenue.

Turner came around. Jostling backs screened from him the assassins' victims. He picked up Jimmy's dead body, then thrust at the human barrier to reach the girl and the youth. He got to the interior of the jabbering crowd, knelt beside the pitiful bodies.

In a final convulsion, Sue Orling had raised to her elbows. The youth was dead. No one could have lived a second after bullets had made that stitching of holes across his heart.

Doc Turner's eyes went to the girl. The murder-spray had caught her lower down, shattering thighs and hips, but there was a faint pulse in the wrist his fingers took.

"Ai-ai-ai," some woman yammered above him. "Vot ah terrible teeng!"

"It's a mercy," another voice said, "that they have no mother or father to mourn them."

A blood-stained market bag slanted against Sue's honey-colored hair like a surrealist caricature of the prevailing grotesque mode in hats. The pallid face had a sort of pert prettiness, but it was far from real beauty. The rouged lips were starting to move!

Doc bent closer. "Jen." It was the merest shadow of a voice that breathed the name. "Tell Jen... not go... tell her it's... a school... for hell..." It faded into a long sigh and the pulse under the old druggist's acid-stained fingers fluttered like a frightened bird. Stopped.

"What's all this?" a gruff voice demanded. "What's going on here?" A blue-uniformed policeman pushed through the crowd. "Gor!" the cop grunted, seeing what lay on the sidewalk. "Who done this?"

Doc lifted erect, his eyes the blue of Antarctic ice, his red-threaded nostrils pinched together. "I don't know," he said through tight lips. "I don't know yet, but I'm going to find out."

THE morgue wagon clanged away and the swish of a street

cleaner's hose, washing carmine stains from the sidewalk outside

Turner's drugstore, underlay the shuffle of the dispersing crowd.

"She knew too much about someone, Jack," Doc murmured, "and was

going to tell what she knew." Doc's lean fingers took a small

object from a drawer behind the old heavy-framed showcase. He

dropped the object in his pocket.

"She was a damn sweet kid, and clean as a whistle." Jack Ransom's freckled and youthful countenance was somber. Barrel chested, muscular, his carrot-hued hair seemed to glow with a light of its own in the dingy interior of the old-fashioned pharmacy. "She never had time for fun, holding down a typist job and making a home for Jimmie out of their two-room, cold-water flat." More than once Jack's strength had complemented Doc Turner's mental agility in the old man's never-ending struggle to protect his people. "I've seen her around a bit, and I can't figure her mixed up in anything off-color."

"Neither can I," the aged pharmacist agreed. "Not willingly. But she had become involved in some criminal scheme. With her last breath she tried to voice a warning against it. Someone, some girl, is in danger. Sue Orling gave her life to save that girl, and it would be tragic if she has given it in vain."

"Which means we got to finish the thing for her." Jack's white-toothed grin was matched by no gleam of humor in his eyes. "Okay. What have we got to go on?"

"Only that the thing has to do with some school—a 'school for hell,' she called it—and that the name of the girl she wanted to warn is Jen. Find Jen and we'll find out what the 'school' is."

"Jen," Ransom repeated, his brow wrinkling. "Jen. Holy Moses, Doc! One out of ten of the young females around here is called that. What are we going to do, ask every one of them if she knew Sue Orling? Or put an ad in the paper?"

"I'll do either or both, if there's no other way," Doc answered, "but I have a feeling that even if that were successful, we'd find the Jen we want too late." His fingers drummed the showcase. "I've a feeling there's desperate need for haste. Look here! You've just been talking about how hard Sue worked at her job and her home-making. Isn't it reasonable to presume she had little time to make acquaintances in the evenings? That 'Jen' is someone she worked with? If there was only some way to discover where—"

"I can tell you that. I took her to work in my flivver one morning in a pouring rain. It's the Ideal Shoe Company, that big factory down by the River. First thing tomorrow morning I'll go down there and—"

"Wait!" Doc interrupted. "Wait. The Ideal Shoe—I've heard that name very recently. I have it!" There was sudden excitement in his voice. "Henry Corbin, the insurance man who has desk room in Garvan's real estate office up the block, was in here yesterday afternoon flushed with his success in securing a group life policy on all their employees. He had a list of them. Do you happen to have any idea where he lives?"

"He's got his home address and telephone pasted on the door." Jack wheeled, strode toward the front of the store. "If he's got that list I'll be back with the rest of Jen's name." The street door slammed behind him.

SUE and Jimmie Orling and an innocent bystander died at

approximately seven-thirty that Saturday. It was not quite ten

when Doc Turner and Jack Ransom climbed a rickety tenement

stairway amid the strange, musty scent that is the odor of

poverty.

On the third-floor landing, a gas-jet spread wavering light over dingy walls and doors. Jack Ransom stopped at one of these. "This is it," he said. "The widow Szibeck's." The knuckles of his big fist thumped on the scabrous wood. "They're probably all asleep."

"I hope so," Doc murmured. He shivered a little, inside his shabby topcoat. The damp chill of these never-heated halls was penetrating his old bones. "I hope they're all asleep, and safe."

There was shuffling sound within the door. "Who's there?" a woman's voice demanded. "Is dot you, Jen?"

The eyes of the two men sought each other. "It's the druggist from Morris Street, Mrs. Szibeck," Doc called. "I'd like to speak to you a minute."

The panel was thin and a gasp was distinctly audible. A lock clicked. The knob rattled and the door opened on a heavily built woman in a shabby, clean kimono; her black hair, hung in two heavy braids, threaded with gray; her high-cheek-boned countenance was netted with wrinkles.

"This is my friend, Mr. Ransom," Turner said as the two stepped past Girda Szibeck into a sparsely furnished kitchen lighted and warmed by the red glow from a coal range. "You'll have to pardon us for calling so late, but something has come up that makes it important for us to talk with your daughter Jennie."

"Jen?" Mrs. Szibeck closed the hall door, turned to her visitors. "She is not home." Her hands, big knuckled and harsh skinned, plucked nervously at the hem of her wrapper.

A little muscle twitched in Doc's seamed cheek. "When do you expect her back?" he asked gently.

"I—I don't know." The trouble in the woman's tired eyes deepened. "She don't say."

"She out stepping with the boy friend?" Jack suggested, hopefully.

"No. She go alone."

"Ah," Doc's fingers drummed on the edge of the round table that stood, covered with a red-checkered cloth, in the center of the kitchen. He was waiting for Jen's mother to ask what they wanted of her daughter. The question was in her eyes, but she did not ask it. Nor did she invite them to sit down.

She wanted them to go, the quicker the better.

"Can you tell me," the aged pharmacist ended the uneasy silence, "where Jen is?"

"No," Girda Szibeck said and he knew she lied.

Jack knew it too. "Damn it, Doc," he exclaimed. "We're wasting time. Why don't you—"

"Wait." Turner's hand on the youth's arm shut him up. "Let me handle this." He was thinking of what Jimmie Orling had said—rather, failed to say—two minutes before the lad was murdered. "Mrs. Szibeck, Jen told you that she was going to make a lot of money and that everything would be spoiled if it wasn't kept a secret. You don't like the whole idea, but you think of yourself as a foreigner and of your daughter as an American, so you've decided that this affair is just another of the things that happen in this country that you don't understand. You're doing as she told you, but you're terribly worried about it. Isn't that so?"

The woman's lips moved in a barely audible, "Yes."

"Well," Doc went on, speaking softly. "A mother is a mother wherever she is. Your mother's instinct is right. Jennie is in danger. Just what the danger is, we don't know, but it was to stop her from going into it that we came here tonight. We were too late to stop her. I don't think we are too late to save her, but we will be—unless we can find her quickly. Do you understand?"

SLAVIC stolidness still held all expression from the widow's

face, but a sob swelled in her corded throat.

"You must forget your promise to Jen," Doc urged. "You must help us to find her before it is too late. You must tell us where she is."

The sob broke through, became words. "School. School for movie."

"You mean," Ransom broke in, "a school for—"

"Jack!" Turner barked. "I told you to keep quiet." And then to the mother, from whose lips the color had drained, he said, "Where is this school?"

The woman spread her arms wide in a gesture of helplessness. "She don't tell me. She say nobody mus' know."

"Ah," the old man sighed.

"It's the old racket," Jack broke in, irrepressible. "They get hold of these kids, tell them they've got it over the big stars fifty-seven ways in natural talent, but they need training. One of the big companies is running a hush-hush school, all the girl has to do is go to it for a while and—zip!—she'll get a contract for a thousand dollars a week."

"Yes," the mother agreed. "Like dot she tell me."

"Sure," Jack grinned humorlessly. "And just so she won't back out till the course is finished, they asked her to pay a nominal—"

"No." Mrs. Szibeck interrupted. "No. Jen, she don' have to pay nothing. Dot why is secret, or everybody want to go. Teaching, dresses, hair-fix—everything is free."

"Huh!" The youth's jaw dropped. "Free! Then what the blazes—"

"That's it!" Doc Turner's eyes were bleak. "That's the clue that this isn't just a petty fraud, such as is being worked in thousands of places all over this country. If that's all it is, Sue Orling wouldn't have been—" He checked himself. "Are you sure you can't help us find out where it is, Mrs. Szibeck? Think. Didn't Jen say something?"

"Look!" Sudden excitement shone in the mother's face. "I remember—Jen go out, call me from stair. 'My odder pocka-book, Mom,' she holler, and then she say, 'Never min'. I remember.' Maybe she mean she got address in pocka-book she take to work."

"I'll bet!" Jack exclaimed. "Where is it?"

"I get." Girda Szibeck was already going into a room beyond the kitchen. She left the door open and her visitors saw an empty double bed in the gloom. Close to it was a smaller one on which lay a sleeping child. Then the woman was back, clutching a large black bag. She thrust it at Doc.

He struggled a moment with its clasp, then spilled its contents out on the table. A powder puff and rouge compact, the five-and-dime's best. A lacy handkerchief. Nail-file and buffer. A swatch of material. A much-folded, grimy movie theatre announcement. A worn photograph of Claudette Colbert. Ransom pawed them over, grunted.

"Looks like we've drawn a blank, Doc. I—"

"What's this?" Turner's hand came out of the inside of the reticule. "Stuck in a rip in the lining." 'This' was a slip of paper, about business card size. The old man peered at it. "Something written—" He held it out to Jack.

"Four thirty-seven River Avenue," the latter read. "Hell! This can't be it. That's a radio-parts factory. She was probably trying to get a job—"

"The number is four thirty seven and a half," Doc said quietly. "Not the factory. One of those old houses in behind the factories and warehouses, left over from the days when there was no River Avenue and green lawns sloped down to the water's edge."

"That's it, then." Jack wheeled to the hall door. "Anything could be pulled off in one of those old dumps and no one would know about it. Let's go! We'll get a squad of cops and raid—"

"On what charge?" the old man asked. "The police have to have a search warrant and no judge will issue one without some evidence that a crime is being committed on the premises."

"Okay! We'll go get the evidence!"

"Just walk in and ask for it, eh? These people will give it to us, for the asking. They're very obliging. Do you recall how they obliged Sue Orling this evening?"

Jack Ransom paused with his hand on the doorknob, his brown eyes sultry. "Don't tell me you're quitting, Doc. Don't tell me you're throwing up your hands."

"Hardly," Doc Turner clipped. He turned to Mrs. Szibeck, who seemed bewildered by the swift exchange in a language of which her years in this country had not given her full command. "Don't worry, my dear. We'll take care of Jen... Come, Jack, I'll tell you my plan on the way down."

IN a lightless chasm between towering windowless warehouses

that line River Avenue, the old residences haunched. Only here

and there in the dilapidated row did any light show.

Doc Turner, more frail looking than ever, walked soundlessly through the shadows of the shadowy, forgotten alley, thinking of the long-ago day when these derelicts were palatial mansions, standing stately each in its own garden. On a night like this they would have been gay with laughter and music...

Like the wraith of some departed orchestra, faint music came from the darkest of the houses. It was the one he sought, and now that he was close to it he saw that black blinds were drawn tight behind its windows. It appeared deserted, but Doc knew it was not.

As he rounded the house, the sound of music seemed perceptibly louder. "Yes," the old man murmured. "I remember. These are the windows of the old ballroom."

A fleck of brightness cut the stygian blank of the wall. Doc stopped short. There was a rent in one shade. The window was high above him, but the ancient mortar had crumbled away, leaving deep chinks where his fingers and toes found easy hold.

His head came level with the sill, deep and generous as the builders of those more spacious days designed everything. He climbed further. There was space enough for him to stand, albeit precariously, on that sill.

The pulse of the music emanated from a hole in the grimy pane, and in rhythm with it came a tapping of light feet. "One, two, three, kick," he heard some one say. "Left turn. Right turn. Front. One, two, three, kick..."

Doc shifted a little and he could see through the rent in the blind. The big, bare room was lighted by four kerosene lamps placed on its floor. Within the square these outlined, a row of four girls tapped and pirouetted and kicked while a tall, thin man with a face too narrow and too long counted for them.

The girls' slim, young bodies were clad only in dancing shoes, scanty shorts and slight brassieres. Their muscles rippled under silken skin, and their hair made misty clouds about their eager faces. Jen Szibeck was the smallest of the four, brown-haired, sharp-featured, lovely in her youth and excitement. Doc recognized the other three. He'd sold their mothers nipples and nursing bottles for them, had watched them grow up...

"Right turn." The tall man chanted in time to the music of a phonograph standing just beneath the window outside of which Doc stood. "Front. One, two, three, kick. More pep, girls, kick. High, high, three, kick..."

Two men were standing beside the phonograph, watching. Doc could see only the top halves of their heads. One was gray-haired, thick-eared, his eyes set too close together under a narrow brow. The other's hair was sleek and black, his eyes black and ferret-like with bluish pouches of dissipation under them.

"What do you think?" the grey-haired one said, low-toned. "Pretty good, hey?"

"For me, no." The intonation was foreign, Latin. "Zey are too theen, too boney. But zat ees ze way ze touris' een Callao like zem. So—" He shrugged.

"You got the idea, Ramiros; The customer is always right. I'll tell Garron you'll take them, then."

"Not so queek. You say ees five. Ees only four here."

"Hell. We had five lined up for you, but one got wise and we had to fix her so she wouldn't talk. What's the difference? You save the grand you were putting out for her."

"Ze gran'?"

"A thousand bucks. That's right, ain't it?"

"No, no. Ees not right, Seņor Dolgar. You leave me, how you call?—een zee lurch. In ze wintair it ess ver' busy een Callao. Eef I have only four girl I lose money." Ramiros sounded excited. "I no like thees whole affair. First you tell me I mus' say I am cinema directeur, tak' zem on location. Zen you mak' me come here in zee night. Now you leave me in ze lurch, wis' my boat she sail in ze morneeng. No. I say I pay five tousan' for five, but for four I pay only three."

DOC TURNER'S throat clamped. He had met and fought all sorts

of human depravity but this calm haggling over the price of human

beings sickened him.

"You'll have to talk that over with the boss," he heard Dolgar say. "Wait. I'll get him over."

The phonograph squealed to a stop. "All right, sweethearts," Garron's voice came to the eavesdropper. "Go get dressed and start studying your parts for the voice test. I'll call you as soon as Mr. Ramiros is ready to watch you put on the little sketch we've worked out."

He turned and started across to join the other two men. The girls ran off, chattering, and Doc leaned against the window, trying to see where they went. A door slammed shut. Nails screeched as an old fastening pulled loose from rotted wood. He was falling inward! He clawed at nothingness, thudded to the floor inside. He rolled, and lay very still as he blinked up at a bulldog revolver in Dolgar's fist.

"Hold it," Garron said, coming up. "We don't want to plug him in here unless we have to." There was a sort of reptilian quiet about him that was somehow more vicious, more menacing, than Dolgar's empurpled rage. "I'll keep a bead on him while you take a look outside and see who else is around." His weapon was an automatic, but it was no more cruel-looking, no more menacing than his thin mouth. "Take it easy, Ramiros. He's got nothing on us—yet."

The man from Callao was plastered to the wall, his pupils dilated, the pallor underlying his olive complexion turning it a sickly green.

"Nossing?" he gibbered as Dolgar climbed out of the window that had betrayed the druggist. "You call nossing zat he have hear' what we say?"

"I don't care what he heard you say," Garron snapped. "If he's got pals outside, it'll be his word against the three of us, and what's more, against the four girls. They can't say anything out of the way has come off here. The worst that can happen is the cancellation of our deal... If he's alone, we won't even have to do that. Once we get the skirts out of here, we'll have nothing more to worry about."

"You weel have nossing to worry," the Latin came back. "You weel have my money an' you can run away. But me? I weel have ze girls wis me, on ze boat an' he weel wireless—"

"He won't radio to have you stopped, Ramiros," Garron said grimly. "Unless there's an RCA station in the grave." He looked down at Doc. "You get me, wise guy? Say. You're a funny-looking shamus! You must be one of the Vice Society snoopers." He kicked a stinging toe into the old man's side. "Is that what you are, grandpa?"

"It won't much matter to you what I am," Turner said, "when you get the chair for killing Sue Orling."

The taunting grin wiped from Garron's cruel mouth. "I make you now," he said, low-toned. "You're the mug popped out from behind the drugstore and saw us making our getaway." His lids dropped and the glitter between them was exactly like that which shows beneath a cobra's ocular membranes, the instant before it strikes. "I almost sent lead into you then."

"You're going to be very sorry you didn't," Doc countered, and then the grey-haired thug, Dolgar, was standing above him.

"Not a whisper of anybody else around, Ben," he reported. "We douse this bird and we're in the clear."

"Frisk him," the other directed. "No, wait. Gag him before he takes a notion to let out a yip the girls might hear."

A POLICE prowl car braked to a stop on River Avenue. The red-headed youth who had signaled it hopped on the running board.

"Listen," he gulped. "Doc Turner went to deliver some medicine to

one of them rear houses a half-hour ago, and he hasn't showed up

yet. I'm scared something happened to him."

"The devil!" the sergeant exclaimed. "Doc didn't have no business going in there alone at night."

"That's what I told him," Jack Ransom groaned. "I wanted to go along with him but he wouldn't let me. He had his day's receipts in his wallet, too."

"You know what house he went to?"

"Sure. Four thirty-seven and a half—"

"Let's go," the sergeant barked. "Come on, Hen. We'll take a look into this."

Seconds later Jack and the two cops trampled up the creaking front steps of 437 1/2 River Ave., pounded on the door. Almost at once it was opened by a burly, grey-haired man in his shirtsleeves who seemed no more upset over seeing them than any innocent householder might have.

"What's up?" he asked.

"You see anything of Doc Turner?" the sergeant demanded. "Little man with white hair. He's supposed to have brought some medicine here, little while ago."

Dolgar shrugged his shoulders. "You got me, pal. Nobody like that's been here. Nobody's sick here, either."

"You're a liar," Jack flared. "I saw him come in here and I've been hanging around—"

"Easy," the police sergeant said. "Easy, bud." And then to Dolgar, "You don't mind if we take a look around inside, do you?"

"Cripes! We're having a little party—but go ahead." He stepped aside and they tramped in.

Twenty minutes later they were at the door again. They had been through the old house, from top to the bottom. Jack Ransom had demanded of Jen Szibeck what she was doing there, and she had answered coolly, "What business is it of yours?" They had been down cellar and up on the roof. And had found no trace of Andrew Turner.

"But he must be here somewhere," Jack insisted. "I saw him go in and he didn't come out. They must have hidden him somewhere."

"Do you mean to tell me," the sergeant said, wearily, "those girls in there would cover up a snatch, even if these three gentlemen had pulled one off?"

"No," Ransom had to admit. "No, they wouldn't."

"So cut the comedy. We got some patrolling to do." He turned to Dolgar and Garron, who had accompanied them on their search. "I'm sorry this screwball put us up to making so much trouble for you."

"That's all right, officer," Ben Garron responded evenly. "You were just doing your duty. Good night."

"Good night." The sergeant's burly shoulder jostled Jack out of the door and it closed behind the three. "I've got a good mind to pull you in for drunk and disorderly," he growled as he forced the reluctant redhead down the creaking wooden steps from the porch. "You damn—"

"Wait!" Ransom exclaimed, wheeling around. "Wait!" he repeated, low-toned, dropping to his knees on the bottom step. The officers stared at him as he put his face down by the worn tread and appeared to sniff eagerly.

"Drunk nothing!" the patrolman exclaimed. "He's nuts. He thinks he's a dog."

JACK straightened, grabbed the edge of the tread with hands.

The cops were too startled to do anything before he had ripped

the board loose. "Light," he demanded in a choked voice. "Shine a

flashlight down in here."

"What?" the sergeant exclaimed; but he obeyed. His torch beam went into the narrow space Ransom had uncovered. It touched upon Doc Turner, then on his shoes and ankles around which a rope was lashed.

"It's him!" Jack yammered, his head down in the space, peering in. "It's Doc. And there's a tommy-gun near him, and a box of ammunition. Now am I crazy?"

The two cops whirled, went up the porch steps again and commenced pounding on the door. There was sound of running feet inside. Jack dived past the cops, his shoulder ramming the ancient panel, smashing it in. A girl screamed; a man shouted. There was a hammer of gunfire. The cops were down on their knees, orange-red jets streaking from their guns at the two thugs who fired back at them from behind the stairs. The black-haired Ramiros ran across the line of fire, maddened by terror, went down like a doll with the sawdust gutted from it. Ben Garron spun out of his covert, thumped into the wall, slid down along it. Dolgar flung his revolver away, screamed, "I give up! Don't shoot—I surrender!"

The silence that descended on that ancient house was like an explosion, so tremendous had been the thunder of gunfire it succeeded.

The patrolman, bleeding from a bullet-groove across his cheek, manacled the wild-eyed Dolgar. The sergeant, holding a shattered left wrist with his right hand, turned to Jack, who miraculously was un-wounded. "How did you know Doc was under there?" he demanded. "How the hell did you spot him?"

"I smelled him." Jack grinned.

"Smelled him?"

"I smelled ether," Jack explained. "Doc never carries a gun when he's on a prowl, but he always sticks an ampule, a little thin-walled glass bottle, of something like that in his pockets. If he gets in a jam, nobody ever bothers to take that away from him, and it's come in handy more than once. I suppose he heard us trampling around and couldn't yell or attract our attention any other way. He rolled over on the ampule and broke it, hoping I'd smell it. And I did."

Doc confirmed that, when they had dragged him out of the cubbyhole under the stairs where he'd been stowed to wait for death. He confirmed it, that is, after he was revived, since the ether that had signaled his presence had also put him to sleep while the battle raged.

"They hid me in there until they'd have time to get the girls out," he explained. "And that's why our plan almost misfired, Jack. You see," he told the sergeant, "I deliberately let them capture me so that my young friend here would have a legal reason to induce you to invade this house. We figured, rightly enough, that thinking me alone they would try to avoid gunfire until they could consummate whatever design they had against the girls. But they were almost too smart for us."

He sighed, smiled wanly. "I—I know what the grave's going to be like, now. The smell of moldering earth, the worms crawling over one. The darkness, and then—oblivion. It—I'm a tired old man, Jack. I sometimes think it would be nice to fall asleep and never wake up again. But—I've got so much to do!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.