RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

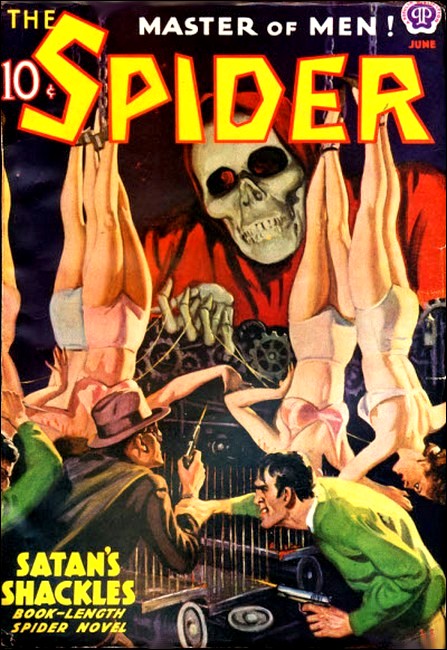

The Spider, June 1938, with "Terror's Twilight Sleep"

Over the river's dark surface rowed the strange crew of corpse corsairs, their captain a man who stole brains as well as booty—and only Doc Turner knew how to trap this thief who threatened to plunge the whole world into a twilight sleep of terror!

THE sprawling trestle of the "El" roofed Morris Street with blackness. The tumult of the slum day had faded to a restless post-midnight hush, but a timorous breeze, sifting up from the river, could not sweep the deserted thoroughfare clean of the odor of poverty. It was a distinctive compound of spoiled vegetables, of sweat unwashed from toil-wearied bodies, of shoddy clothing and rotted shoe leather.

From the windows of a drugstore two huge glass bottles laid red and green light-streaks across the debris-strewn pavement. In the doorway of the grimy pharmacy stood a bent, feeble-seeming old man. His cheeks were gaunt and netted with fine wrinkles, faded-blue eyes fogged with weariness, hair silky white.

His long day was ended, but Andrew Turner was loath to leave the shop where he had spent more years than he cared to recall. There might still be someone in need of him, some infant suddenly choking with the croup, some—

The thud of a footfall from around the corner turned Doc Turner toward it, his gnarled, acid-stained fingers tugging at the bushy droop of his mustache. The sound came again. A frown of perplexity creased the druggist's wrinkled brow.

There was something peculiar about the cadence of those footfalls, something too precisely measured—too unresiliently ponderous. It was almost as if not a human but a machine pounded, thud-thud-thud, on the concrete. Yet the sounds were unmistakably footfalls, and what possible machine could be walking, thud-thud-thud—along Hogbund Lane?

Abruptly, the night seemed to tense, quivering with a weird dread.

The strange sounds came nearer. They came slowly, and with a strange quality of inevitability. Almost, the thought trailed across Doc's brain, like the inevitability of death itself. The old druggist waited... and while he waited his breath caught up sharply in his lungs.

A shadow slid along the sidewalk. But the street lamp that cast it was too far down the block to give it definite shape. Then something moved around the store window's corner and, thud-thud-thud, a form came into view.

Pent breath hissed from between Doc Turner's teeth, and a wry smile twitched his thin lips. It was a man, squat, burly, who turned now and came toward Doc along the Morris Street sidewalk. It was Anton Czerno, a pushcart peddler who each day took his stance at the curb just a little way down the line from here.

Czerno came into the green glow from the drugstore window, and once more Andrew Turner's lids narrowed. The huckster's knobbed and unshaven countenance was as devoid of expression as a cardboard mask, his dark eyes unfathomable pits under the jutting, shaggy eaves of his brows. His torso was rigid. His arms hung stiff and straight at his sides. His left leg lifted angularly as the leg of a puppet might if it had been tugged at the knee by an invisible string. It thudded down, and the right leg jerked stiffly up, jerked down, striking dull sound from the pavement. The left leg lifted...

"Anton!" Doc cried, stepping from his threshold. He snatched for the man's arm. Czerno's left leg thudded down, the right jerked up... "What's the matter?" Turner's fingers closed on biceps hard as stone where there should be the elasticity of flesh. "What's wrong with you?"

The gripped arm tore from the old druggist's grasp, and the peddler pounded straight on, thud-thud-thud, without pause, an animated mannikin staring directly ahead with dreadful, unseeing blankness.

"Anton!" Doc cried, more sharply, getting a new hold on Czerno's shoulder. "Wake up!"

His grip, firmer this time, swung the huckster slightly sidewise. The arm that hung from the shoulder the pharmacist grasped now swept up stiff-elbowed, then swung back like a club pivoted at its upper joint! It smashed against the old man's chest, sent him reeling against the cold smoothness of his own display-window pane.

Anton Czerno pounded on, unswerving. His arm dropped back to position against his flank, and that was the only evidence of the blow it had dealt.

Palms flat against the plate glass behind him, Doc Turner stared after the robot-like figure. Abruptly, he thrust away from the window, an exclamation on his lips.

A long wire, discarded from some fruit box and invisible on the dim sidewalk, had trapped Czerno's ankles and pulled his legs from beneath him. He toppled forward, rigid as a falling statue, making not the least effort to save himself. He struck the pavement—

Then he lay without any movement at all.

DOC TURNER reached the still figure, dropped to his knees

alongside it. His fragile hands touched the close-cropped head,

rolled it. A reddening bruise on the forehead showed where stone

had met the skull, thumping from it whatever strange sort of

consciousness it had held. But the thick wings of the nostrils

fluttered, and in the grooved temple a pulse throbbed.

"Concussion," Doc muttered. There was no dribble of blood from nose or mouth-corners. "Not so bad." The druggist slid an arm beneath the flaccid form, heaved. It flopped over, but was too heavy for the old man to lift.

Turner glanced around for aid. Morris Street was still empty of life, shadowed and desolate.

Doc shrugged, lifted erect. He darted nimbly back to his own store, trotted past showcases whose wood was grimy white and whose glass fronts were scratched and hazy. He went past the end of a scarred sales counter at the rear, into a narrow room walled by shelves which held glittering bottles, save where a prescription counter stretched its clean-scrubbed length.

The druggist snatched open a drawer in the face of this counter, plucking out a pledget of absorbent cotton half the size of his fist. He straightened, took from the shelf in front of him a glass-stoppered bottle whose contents glinted faintly yellow, twisted the cork from it and spilled some of the liquid on the flossy white ball in his hand.

A pungent ammoniacal reek stung his eyes, but the wrinkled pharmacist re-stoppered the bottle and retraced his steps. Doc reached the huckster, once more knelt beside him. The man was still unconscious, eyes closed. The mark on his forehead was growing bluish as the blood under the unbroken skin clotted.

Turner noted the shallow rise and fall of the grimed, collarless shirt that covered a broad chest. He nodded, placed against Czerno's nostrils the cotton he'd soaked in aromatized ammonia.

The peddler's inhalation through the pungent floss was a soft whisper. A shudder ran through the sprawled form. The mouth gaped, expelled air, pulled it in again wheezingly. The head rolled toward the curb, away from Doc. The grimed fingers on that side lifted, curling as if to grasp a hold on something two feet above its owner, then hesitated as if in surprise. The hand nearer Turner thrust at the sidewalk, shoved the huckster up to a sitting posture.

"What the hell!" the man spluttered. His head twisted so that Doc could see his opened eyes. There was puzzlement in his widened pupils, and dawning terror. "Where's my wagon? Where... What happened?"

"Take it easy, Anton," Andrew Turner said calmly, settling back on his heels. "You're all right. You're quite all right now."

"Doc!" Czerno muttered. "How come you're here in the pushcart garage? How come—"

"You're not in the basement where you fellows store your carts overnight. You're on Morris Street." The druggist's tone was conversational, soothing. "Don't you remember coming here?"

"Morris Street?" The huckster looked around, his neck cording. "But—but just now I was pushing in my wagon from the stairs and—" He hesitated, fumbling dazedly for recollection.

Doc Turner murmured, "Yes, Anton. And what?"

"I saw that guy—how you call him... that guy—" Then darkness suddenly smashed into Doc's skull from a crashing blow on the back of it; and he knew no more...

"DOC! Doc Turner!" The voice came out of a swirling void of

blackness. Hands were trying to pull him back from the weltering

sea of oblivion into which he had sunk. "By Jupiter," the hoarse

voice said. "He's passed out for good. I'll have to call the

bus."

"No," Andrew Turner muttered. His eyes opened, and he saw heavy-lidded eyes peering anxiously down at him from beneath a visored blue cap. "I'm all right, Tim Reilly, except for a nasty headache in the wrong place." He rubbed the back of his head as he sat up, feeling sickish. "How about Anton? Did they get him, too?"

"Did they get who?" the cop demanded. "Who's that you said?"

Doc twisted to the sidewalk beside him. Czerno wasn't there. Officer Reilly stood spraddle-legged above him, looking worried, but no one else was in sight.

"Was I alone here, when you found me?" the old pharmacist asked, dazedly.

"Sure," said the cop. "I seen you two blocks off, comin' along on my patrol. There wasn't nobody else around—nobody at all. They get anything from you, Doc?"

Turner felt the outside of his left trouser pocket. His wallet was still there. "No, Tim. You must have scared them off before they had a chance to. They didn't get anything from me." He let the patrolman help him up.

"How'd they manage to get you out here and slough you?" Reilly fished in a pocket, brought out a battered notebook and the stub of a pencil whose point he moistened between his lips. "I got to make a report."

"Forget it," Andrew Turner said gently, "and save both of us a lot of bother. I didn't see who hit me. I don't know anything about him." Telling the story to the police would result only in getting Anton Czerno in trouble. The cops would insist his peculiar actions had been a stall to get Doc out of his store and in position to be attacked. "Something like this being pulled off on your beat will get you a black mark on your record, may lose you that sergeancy you're out for."

"Well," Reilly grunted, closing his notebook, "maybe you're right, Doc. Maybe you're right."

"THE way I figure it, Doc, is that someone was listening in

from that vestibule opposite which Czerno was knocked out. When

the eavesdropper learned that Anton remembered too much of

whatever happened in the pushcart garage, he conked you before

you could hear the name Anton was about to spill. Then he lugged

Anton off."

The time was a little past noon of the day after the events just related. The place was the prescription room of Turner's Pharmacy on Morris Street. The speaker was Jack Ransom.

Ransom was not much taller than Doc, but less than half the druggist's age. Good humor crinkled the corners of his eyes, the only lines on the strong-jawed young face. A powdering of freckles across the bridge of a somewhat flat, upturned nose matched the carroty thatch of his hair. He was broad-shouldered, barrel-chested, and the fists at the end of his muscular arms were large and very competent. They had need to be. Often they were called into action when Andrew Turner's shrewd brain had done all it could, and brute force became necessary to subdue some human coyote who believed that the people of Morris Street were friendless as well as poverty-stricken.

Ransom said, digging at the edge of the prescription counter with a thick-nailed thumb, "What I'd like to know is what, exactly, happened to Czerno? What did he know so incriminating to someone that the poor fellow was killed—in that particularly outrageous way?" The flat of his hand slapped a newspaper lying open on the counter.

The item was headlined, read—

BRAINLESS BODY FOUND IN RIVER

Harbor Police Squad early this morning found floating in the river a gruesomely maltreated man's body. The top of the cadaver's skull was sawed away and the brains removed. As if this were not enough, the corpse's lips had been tightly sewn together with copper wire.

This latter macabre procedure is a familiar device of gangsterdom, used to indicate that the victim had met his fate because he "talked too much," and to warn others against imitating this error. Identification of the dead man as Anton Czerno came through a peddler's license in his pocket.

The authorities admit that they are completely in the dark as to the motive behind the crime, and without any clue to its perpetrators.

"The cops don't even bother to crack wise about the progress they're making on the case," Ransom said bitterly, glowering at that final paragraph. "Nobody particularly gives a damn what happens to a Polack peddler from Morris Street. His folks haven't any vote, and there wouldn't be any glory in it if a dick did turn up the lug that sawed off the top of his skull and scooped out his brains."

"That's nothing new, son," Doc Turner said. "Even before the paper came out with this item, I knew this business was up to us. Before I knew he was dead, I was already talking to the other peddlers who store their carts in the same basement Czerno did. I was trying to get some hint from them of what happened there last night."

"Find out anything?"

"Nothing to help," Doc admitted. "Anton had had a hard time disposing of his load of kohlrabi and rhubarb. He stayed out an hour after the others had put away their pushcarts. They'd all left the basement when he finally gave up and took his cart to it."

"But he said—" Jack began.

"That he saw someone there," Doc filled in, nodding. "Precisely. But it was none of his fellow hucksters. I've checked, and they all have perfect alibis."

"Why wasn't Anton bumped right there and then?" Ransom demanded.

"Because murder wasn't the intention of the ambusher."

"Hell," Jack argued, "the couple dollars the guy had on him wouldn't be bait enough for a stick-up."

"Robbery wasn't the motive either," Doc said softly. "Jack, there is something almighty queer behind what happened last night. I haven't the least idea what it is, but I get an icy chill creeping up my back thinking about it. The same kind of chill, my boy, that I got this morning. The woman with whom Czerno boarded came in here and told me, in answer to my apparently careless questions, that he returned just in time for supper last night, ate it, and then went out again without saying a word to her or anyone else."

"Hell," Ransom exploded, "if he was all right, then what's the idea of worrying about what happened in the pushcart garage?"

"Because that was the last thing Czerno recalled when the aromatic brought him back to normalcy." Doc's eyes flashed. "Between about seven last night and twelve-thirty this morning, Anton Czerno was a sleepwalker—his brain as surely disconnected from his body as if his skull already had been trephined and the grey matter emptied from it. How that was brought about, and the reason for it, is why I was knocked out—to keep me from discovering it. Czerno was carried off and killed in that terrible manner to keep him from putting me on the right track."

"Look," Ransom put in, "maybe others beside Czerno could do that. Maybe that's why the Polack's lips were wired, to warn them the same thing will happen to them if they squeal."

"Precisely," Doc agreed, nodding. "After that threat, we're going to find it impossible to get anyone to talk. But I intend to unearth what's behind Czerno's strange death. I don't know how to start, but I'll work out a way. I—"

The rap of a coin on a counter outside stopped him. It was the usual signal that a customer was waiting, and Turner took his time going out front to take care of him. The slam of the street door, just as the druggist reached the curtain, hastened him through the opening in the partition.

No one stood at the sales counter. No one at all was in the store. There was only the dim, cloistered quiet of the old shop, the dingy-white shelving—and the roar outside of a car shooting away from in front of the store...

DOC TURNER'S lips tightened under his mustache. Someone had

been out here. Had that someone been listening to his talk with

Jack? If so, why the rap of a coin to stop that talk and summon

Doc out there? He peered about. Something was on the counter that

had not been there before—a paper-wrapped, string-tied

package. It lay on the worn wood, a cube about a foot square, and

there was something ineffably ominous about it.

"I'll be damned," Jack Ransom said. "Someone put that there and beat it." He had come silently out through the curtain and was alongside the old pharmacist. "What's the big idea?"

"Best way to find out is to open it," Doc answered, moving to the counter. He reached hesitatingly for the package.

The paper rustled under the old man's steady fingers. It folded open to reveal a cardboard box. Doc lifted the lid from the box. He put the lid next to it on the counter, very carefully. But he wasn't looking at it. He was looking into the box. His seamed countenance was the color of ashes—suddenly the face of an old, old man.

Inside the box was a bed of tissue. On this rested a bowl- shaped object. The thing was an odd, greyish white and glistened as if slightly moist. It was the top of a skull, skinned, washed, meticulously cleaned.

It was the top of Anton Czerno's skull. As if to remove any doubt of that, a spiral of fine copper wire lay in the concavity of the bowl. The end of the wire was sharpened to a needle point.

Jack Ransom's hands clutched the edge of the counter. Damp sweat filmed the greenish hue of his countenance. "Gawd," he groaned. "I feel sick."

Doc took up the box-lid from the counter and replaced it. He folded the paper in which it had come around the box, very deliberately matching the original creases. He pulled a length of cord from the ball under the counter and tied it around the cube-like package.

"Sewing Czerno's lips together was a warning to no one but me," he sighed. "And this is a message making sure I understand it. 'Keep out!' it says, 'or you'll get the same dose.'"

"What—what are you going to do?" Ransom stammered.

Andrew Turner was frail-looking and now very tired. But he said, "I'm going to unearth what's behind Czerno's strange death."

Ransom's hands tightened, slowly, into sledge-hammer fists. "Let's get going, then. What are we waiting for?"

"For the sender of this to make a mistake, my boy." Doc's smile was altogether without humor. "That's all we can do."

"The devil it is," the youth objected. "We can trace that box, the paper it's wrapped in, the cord it was tied with. We can examine it for fingerprints. We can find out where the tissue was bought."

Turner shook his head. "No, Jack. The man or men we're up against are too clever to be trapped as easily as that. If you don't think so, see if anyone can give you a description of the person who just ran out of here, or of the car in which he drove away."

"I'll do just that," Ransom grated, and he plunged out.

Andrew Turner picked up the package and went into his prescription room with it. He pulled open the bottom drawer in the cluttered roll-top desk at one end of the laboratory, shoved an accumulation of old catalogs back in it to make room, deposited the gruesome box within the drawer—then shut it.

The outside door slammed once more. Doc recognized Jack Ransom's walk, coming toward the back. The carrot-top shoved through the curtain, and the old druggist asked, "Well?"

"You were a hundred percent right," Jack reported. "A couple of drunks got into a slugging match near the other end of the block, and everybody was gaping at them. Our visitor could have slugged you and carried you out of here on his shoulder and nobody would have noticed it."

"The fight was staged just for that purpose." Turner nodded. "If we had a chance to examine them, we'd find your so-called drunks were no more intoxicated than I am."

Jack grinned. "You'll have just that chance," he said. "One of them started chasing the other, and the first one ran right into Tim Reilly's arms as the cop came around the corner. For some reason, Tim's bringing him here."

"We didn't have to wait long," Doc murmured. "Not nearly as long as I expected."

The store's street door could be heard opening once more, and crowd-buzz drifted in. "Get back, the bunch of you," Reilly's husky voice commanded, "before I start using my club."

Doc and Ransom went out through the partition and saw the cop shutting the door on a shoving, curious-faced mass of humans. He was using only one hand to do that because the other had hold of a man's arm.

THE man was tall, collarless, shabbily dressed. There was a

smear of black across his narrow face, and his lax hands were

more black than flesh-colored. He stood quietly, as if there was

no life in him. His eyes were fixed straight ahead and had no

luster.

Reilly got the door shut and turned. "Sorry to bother you, Doc," he said, "but I wish you'd look this guy over. He's got the stink of whisky on his breath, but he acts kind of queer to me. I pull in what I thought was a souse, week before last, and it turns out he was sick from in—insul—"

"Insulin shock," the druggist supplied. "He was a diabetic and shot too much insulin into his arm. He'd forgotten to have a piece of sugar along to neutralize the reaction."

"Yeah," the patrolman agreed. "That's what the police surgeon said. This guy almost passed out. I got the lacing of me life for it, so I made up my mind I wouldn't pull in no more drunks unless I was sure they really were drunks. Will you give this lug a gander?"

"Glad to," Doc answered. "Bring him in back, and I'll examine him."

"Thanks," Reilly grunted. "Come on, you." He started moving, and his prisoner came with him. The man moved stiffly, as if he were a puppet actuated by invisible strings. His legs jerked up and down, angularly... Doc had seen a gait like this!

"That's shoe polish he's got on his hands and face," Jack Ransom whispered. "I've seen him hanging out down at the square with one of them shoe-blacking boxes. The other wrecks playing the same racket call him Caspar because he's as scared of his own shadow as that Milquetoast bird in the comics."

"Not exactly the type to get mixed up in a street brawl, even drunk," Doc responded low-toned. "But even less to be a member of a gang that's very blithe about murder. Perhaps I'm wrong."

The cop and his captive came up to them. Jack pulled the curtain aside so they could go into the back-room. Doc told Reilly to seat Caspar in the broken-backed swivel chair in front of the desk. The policeman had to literally shove the fellow down into it, and then he sat bolt upright on its edge, not lolling as a drunk should do.

"I think I recognize the syndrome," Turner said, getting a wide-mouthed ice bag out of one drawer of the prescription table and a flashlight out of another. "I'll just make a few tests and confirm my speculation."

He took down a bottle of clear liquid from a shelf. Then he unscrewed the cap of the ice-bag, pressed its thin rubber sides together with his hands and went over to the supposed drunk. He put the open mouth of the bag over the man's nose and lips. The rubber expanded with the fellow's exhalation. Doc clapped the screw-cap over it again.

"Bring over that bottle, Jack," he directed.

Ransom obeyed.

"Uncork it and spill about a teaspoonful of the reagent into this bag," the old man instructed. He lifted the cap just enough for the youth to obey, and then put the cap back, screwing it tight. "Here, Reilly—" Turner handed the closed bag to the policeman. "Shake this up thoroughly. You better get back to the other end of the room, because I don't want your shadow interfering with my retinal examination."

The cop put his nightstick down on the counter, took the bag and backed away as far as he could go, shaking the rubber pouch with vigor. Doc picked up the flashlight, switched it on. He bent over Caspar and shone the beam into the blank, staring eyes.

"Look here, Jack," the old man exclaimed. "Look at this." Ransom bent to look into Caspar's eyes, and the act brought his head close to the old man's. Doc whispered something as he flashed the light on and off.

He straightened and turned to Reilly. "All right. Let me have it."

The cop gave the druggist the bag he'd been shaking. Doc unscrewed the cap and spilled its contents into a glass graduate that was standing on the counter. Reilly's eyes goggled, as the liquid came out a brilliant red instead of the clear, water-like color it had been when poured into the ice-bag.

Doc sighed. "Just as I thought," he murmured. "The man isn't drunk. He's got a bad attack of atakexia marinalis. The conditions in the cells over at the precinct house might easily prove fatal."

"Gosh!" Reilly exclaimed.

"Look," Ransom put in, "I know the bloke and where he hangs out. I haven't got much to do this afternoon. Suppose I take him home and put him to bed and stay with him till he snaps out of it."

"That would be the best thing for the poor fellow," Doc replied. "But he's really Reilly's prisoner and—"

"Hell," the cop said, "I ain't tormenting no sick man, fight or no fight. If you think he'll be best off home—"

"I do," said Doc. "All right, Jack. I'll fix up a stimulant to give him when he comes to, and then you can take him along."

"I'll be beating it then," came from Reilly. "Thanks, Doc. I might of got into another mess if I'd run the guy in. S'long." He departed.

"May Aesculapius forgive me," Doc Turner said, chuckling, "for that 'atakexia marinalis.' The good Lord knows mankind is plagued with enough strange-sounding diseases without my adding another jawbreaker to the long roll. Reilly's eyes certainly did pop out when I poured out that phenolphthalein solution from the ice-bag, turned red by the crystal of caustic soda I'd slipped into it when he wasn't looking."

"Yeah," Ransom grunted. "It was a lot of fun. But what was your idea in putting on that show for the cop? What's the idea of having me make the proposition that I'd take Caspar home? In the first place, I don't think the mug's got a home. In the second—"

"In the first place," Doc cut him off, "it's your home to which Caspar is going. In the second place, the idea is that Caspar is going to tell us who killed Anton Czerno, and why."

"Huh?" the carrot-top gasped.

"Listen," Doc Turner said. He talked a long time before Jack finally nodded his understanding and led the dull-eyed bootblack out of the store.

IT hadn't been so bad, as long as day lasted and the sun

brightened Jack Ransom's bachelor's room. But now that the grey

fingers of dusk were fumbling noiselessly at the windows, and the

shadows were creeping out of the corners, the carrot-top was

getting jittery.

The man he knew only as Caspar lay motionless as a log on the leather davenport that could be unfolded as a bed. He'd lain like that for over four hours.

Ransom, oddly enough, was not in the room proper at all. A recess in one of its side-walls had been screened-off to form a sort of kitchenette where he was accustomed to prepare his frugal meals. It was behind this screen that Ransom had been sitting all the long afternoon. He had been reading, or trying to, but now it had gotten too dark in his covert for that. He put his book down on the two-burner stove.

Abruptly, he was rigid!

The whisper of sound from the room beyond the screen continued. It came from no movement of the man on the couch. It was the infinitely slow crawl of metal on metal, the slide of hinge-wings one upon the other. A grin twitched the corners of Jack's mouth. Oiled them so they wouldn't creak! the thought passed across his mind. Good thing I've got sharp ears.

Through the slit between two panels of the screen, he could make out the door to the chamber. There was already a space between its edge and its jamb, and that space was slowly widening. The growing aperture was black and secretive, but there was movement within it, and the gradual materialization of a shape.

A pulse pounded in Jack Ransom's temples.

The door came fully open, and closed again. But now there was a third occupant of the room. He was tall, thin to the point of emaciation, with a narrow face pointed by a clipped Vandyke, sunken pallid cheeks, and burning black eyes whose fevered glow the wide black brim of his felt hat could not hide. The man's clothes were black even to a funereal tie, and his one visible hand was black-gloved. The other hand was in the pocket of his jacket, away from Ransom. That pocket bulged with something bigger than a hand.

The man peered around the room, puzzlement crossing his saturnine face. His eyes reached the couch, paused only briefly on Caspar, lying there.

Jack Ransom's hand came out of his own pocket. There was a snub-nosed automatic in it. "You're covered, mister," he snapped. "Get your hand out of that pocket, empty. Now reach for the ceiling, or I'll drill you."

"Pretty smart." There was a peculiar, lifeless intonation to the voice that sent a shudder through Ransom. "You were waiting for me."

"Yes." Jack stepped out between the tall man and the davenport, his automatic snouting point-blank at the other's abdomen. "We figured you'd come looking for your victim, and we laid a trap for you."

"You're the first one to put anything over on Rass Turksit," his captive said. "I must be slipping." There was no fear or consternation in his vulpine countenance. That troubled Jack. Turksit's eyes were on his, and they were lambent pits of black flame. "Perhaps I still have a way to turn the tables."

More to bolster his own courage than to challenge the other, Ransom jeered, "It's pretty hard to turn the tables on someone who has the drop on you."

"Yes," Turksit whispered. "Yes. If he's alone. But suppose my friend behind you were to..." his voice rose suddenly to an imperative bark. "Get up from that couch and grab him!"

Jack laughed. "That old stunt won't make me turn—"

Behind him fingers suddenly lashed out, grabbed his gun-wrist, forcing it down! Fingers, steel-hard, irresistible, had hold of his other arm, numbing it! Turksit leaped forward, twisting the automatic from Jack's grip. Ransom was stunned by the surprise of that sudden onslaught.

It was Turksit who was laughing now. Ransom's own automatic threatened him. Turksit's laugh was as strangely silent as the snarling laugh of a wolf. When he got through laughing, he shifted the automatic to his left hand, then put his right back into the pocket where it had been when he entered.

It came out—not the weapon Ransom had thought was there, but a glass-barreled hypodermic syringe with a long, keen needle.

Turksit stepped nearer. Before Jack's muscles could tear him from Caspar's hold, the needle plunged into his neck, under the right ear.

"I shouldn't advise you to struggle," Turksit murmured. "It would not be pleasant to have your jugular torn open."

Jack Ransom stood quite still. He felt the sickening seep of some liquid into his bloodstream. The grey room swam about him in a dizzy whirl wherein the only tangible reality were two pinpoints of black fire that were the eyes of the man.

The room steadied, and was still. "Let him go, Caspar," Turksit said.

Jack Ransom was free to move, to lunge at his tormentor. He did not. He willed his fists to close, but they would not. He willed his biceps to tighten and launch blows at the man in black, but his arms hung numb and unmoving at his side.

Turksit was watching him intently. He nodded now. "I didn't give you quite as big a dose as the others," he said. "You will know what is going on. But you have no will—except mine."

Jack wanted to tell him to go to hell, but couldn't.

"Put on your coat and hat," Rass Turksit told him. Jack did exactly as he was told. "Come," Rass Turksit said.

Jack went with him and Caspar, down the narrow, unlighted stairs of the lodging house, out through the foyer that smelled of stale corn beef and cabbage, down the high, brownstone stoop, across a cracked sidewalk and into a black sedan that stood waiting at the curb.

Jack Ransom was in full possession of all his faculties save his will. He had no will. The will of the man with the black-wide brimmed hat and the black, pointed Vandyke was Jack Ransom's only motivation.

The car started off. It ran through debris-strewn, stinking, familiar streets. The slum night closed down, thick, dark and fearful, and the sedan ran through the night, toward the river.

THE black waters of the river lapped greasily at the piles

supporting the enclosed, supposedly abandoned pier to which Rass

Turksit had brought Jack Ransom, three hours ago.

They lapped along the sides of a long, wide-thwarted dory moored to the end of the pier. The sides of that dory were painted a battleship grey, and in the moonless night it was only a patch of darker shadow on the slow heave of the tide.

A half-mile north, three more gigantic shadows loomed out of the shadowed flow of the river. Dimly seen as they were, these were long and graceful shapes, pleasure boats moored off a yacht basin. They displayed only the fitful yellow gleam of their anchor lights, but a hundred yards further upstream, brilliant sparks of green, scarlet and gold outlined a fourth swanlike hull and made of it a fairy ship floating on the murky flood. This was the Morgana, famous corsair of Hampton G. Pierrepont, millionaire playboy, and Pierrepont was entertaining a party of the elite tonight.

From within the closed water-doors of the pier came a vague thudding. Like the dull pound of a machine, it was an evenly spaced cadence, as a dozen oiled rods struck the end of their channels, returned, striking again.

The doors slid open. One by one, six bulky shadows issued out on the narrow apron before them, huddled in strange hesitance. A seventh shadow, tall and thin almost to emaciation, turned from sliding the pier-doors shut again. A command, low-toned, and the five others were dropping, one by one, down into the dory.

Jack Ransom was the fourth of the six to find a seat in the boat. Dulled, apathetic, he awaited while Rass Turksit dropped to the stern, seated himself and got the rudder helm unshipped.

"Put your hands on the oar handles in front of you," Turksit ordered, low-voiced. The robot-like beings seated before him obeyed, in a unison almost weird. Turksit cast loose the painter that had held the dory to the piles, fended it out into the stream. A current caught its nose. "Slide the oar-blades into the water, quietly." Six oars made almost no sound at all. "Start rowing."

Like some ferryboat across the Styx, captained by Charon and oared by ghosts, the grey dory flitted upstream.

Jack Ransom swung, back and forth... back and forth like the rest, and hope was dead within him. Like a wan flame that hope, that somehow Doc Turner might trace and help him, had lived all through the long hours while, in the echoing vastness of the prison-pier, he and the five other men, more dead than alive, had rehearsed that which they were to do.

Now hope was dead. Even at this late hour, Doc might trace him to the pier, but water holds no tracks, and there were no eyes on the river to spy the phantom passing of the dory and its crew of dead-alive.

Impelled by twelve strong arms, it did not take the grey boat long to slide under the overhang of the Morgana's stern. The shuffle of dancing feet, clink of glasses, strains of the orchestra, were more than enough to hide from those aboard the slight thump made by the rowboat's gunwale against the side of the yacht.

Glow from the illumination on deck stripped concealment from the dory's occupants. A burly half-dozen they were, clothed in nondescript garments, and somehow grisly for the fact that the face of each of the six was banded across its forehead and eyes by a narrow grey mask.

"Go!" Turksit snapped. The word set off the train of associations he had so patiently drilled into his bondsmen.

Swiftly and silently, the masked men moved. In a rush, they were ranged all around the dance floor, black and ugly revolvers snouting from their hands at guests, stewards and crew.

Men in creamy summer full-dress, women exposed of breast and back and brilliant with flashing gems, gaped, motionless and white-faced, at the row of silent, terrible apparitions that encompassed them.

THE cadaverous figure, satanic despite the full mask that hid

all of its face, leaped lithely over the rail. "All right," it

cried in a curiously chilling voice, "if you'll all hand over

your money and jewels without a fuss, nobody'll get hurt."

Thick-necked, big-paunched, florid-faced Hampton Pierrepont blustered, "You can't get away with this."

Turksit's only reply was a jeering laugh. He had a bag in his hands and started moving through the crowd, stuffing it with crammed wallets, diamond sunbursts, pearl necklaces and gemmed rings.

Stony-faced and threatening as his companions, something twisted inside Jack Ransom's brain—the brain that was disconnected from his muscles—as Pierrepont's words gave him the last bit of Turksit's scheme. The millionaire was right. The moment the bandits left the yacht, the river would become a certain trap for them. Even without wireless or shore phone, a strong swimmer could reach the shore in two minutes.

But no swimmer would leave this deck until Rass Turksit had made good his escape. For he would go as soon as his collection was complete, but his six subjects would remain to hold the robbed party helpless at the point of their lethal weapons!

Turksit was almost through. His bag was stuffed almost to the limit.

Bitter mockery mixed with Jack's despair. He and Doc Turner had thought themselves unbeatable by any crook. But pitted against the biggest crime of their careers, they had failed miserably.

The youth's thought cut off. Turksit was far across the deck, ripping a sapphire stomacher from its hold on filmy green silk. His back was to a hatchway in the center of the deck—and that hatchway was coming up!

The hinged slab of wood flung back. A small, white-haired figure sprang from it. Doc Turner! But why in the name of all that was holy was he holding the nozzle of an inch-thick hose pipe in his hands?

A fine stream spurted from the mouth of that nozzle. It straightened, sprayed straight for the face of the nearest masked man, touched that face and swept on to the next. In the space of five heartbeats it had circled the gun-holders at the bulwarks, now was spattering on Jack Ransom's countenance.

Fire streaked up Jack's nostrils and into his brain. It exploded there. His eyes streamed tears, and his nose was seared by the pungent reek of ammonia. Blurrily, he saw Doc throw the hose from him and leap now for Turksit.

The thin man heard the druggist coming, wheeled. "Shoot!" he yelled to his slaves, "Shoot them all down."

Doc grabbed at his arm. He straight-armed the old man, then flung himself flat to avoid the spray of leaden death he'd commanded from his slaves.

It didn't come! The masked men were gaping at the guns in their hands, staring stupidly about them.

Turksit jumped up. A fist flailed at him. He ducked it, avoided someone else's snatching hand. He was flying across the deck in great, leaping bounds.

Jack Ransom left his feet in a desperate flying tackle. His outstretched arms clamped about Turksit's knees. The fellow hit the deck with a sickening thud, and a torrent of gemmed wealth poured across the scrubbed boards. A sailor came down with both knees on the thin man's back. A violinist got hold of one of his arms and twisted it. Jack let go his grip, rolled over.

"Doc!" he called. "Doc, you old son-of-a-gun! You don't know how glad I was to see you!"

"THE stuff Turksit injected will have to be analyzed," Doc

Turner said, "but there isn't any doubt in my mind that it is

based on scopolamine—a drug that inhibits the will and the

memory, while it leaves all other faculties functioning. It's a

drug that's used in twilight sleep, you know, and has been

proposed as a truth serum."

"Yeah," Jack Ransom grunted, watching the lights of the police boat for which Pierrepont had signaled, come shooting up the river. "I'll take your word for that. And I know you figured out that if ammonia brought Czerno out from under its influence, ammonia would do it again. But what I don't understand is why—if you tracked me to that pier and even eavesdropped on what was going on inside it—why you let Turksit go as far as he did before you stopped him. Why didn't you call in the cops and have him arrested right then and there?"

Doc smiled wanly. "You didn't happen to read the new sign that was nailed up over the land entrance to that pier?"

"No. What the hell did that—"

"Plenty. The sign reads, Research Clinic of Manhattan State Hospital for the Insane. I recognized Rass Turksit, Jack, as a duly accredited psychiatrist, and a member of the staff of Manhattan State. If I'd instigated a raid before his criminal plans were clearly revealed, he would have claimed that he was engaged in experimentation with certain therapeutic exercises for the cure of lunatics. He would have gone free, and his victims—you included, son—would have been committed to an institution as insane."

"Maybe there wouldn't be so much wrong about that," Jack muttered. "Sometimes I think we're both crazy as bats, taking the chances we do just for the satisfaction of licking a bunch of crooks."

The smile vanished from Andrew Turner's face. "I'm sorry," he said.

"But," Jack Ransom interrupted, grinning, "I'd rather be crazy with you than sane with a couple million other guys I know about—the kind that only think about themselves!"