RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

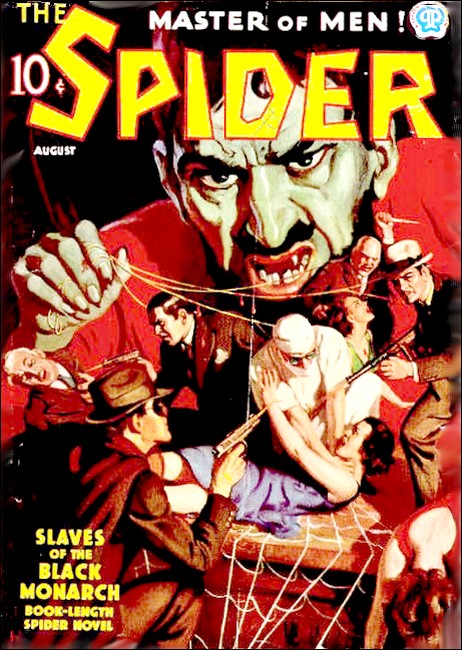

The Spider, August 1937, with "Killer's Circus"

In that Devil's carrousel the grotesque Humpty Dumpty snatched Doc Turner's little adopted foundling—to twist the child's body into a fiend-made freak. But the Doc could work good magic himself when the test came—even if that trick meant swallowing the invisible poison of Death!

THE sun was a red and angry ball low in a coppery dome,

and even in the garage on Hogbund Lane it was like the interior

of a furnace. Jack Ransom wiped grease and sweat from his hands

on a clump of waste. Perspiration was coming through his

undershirt and overalls, making a black, wet splotch on his

barrel chest. His big-boned, freckle-dusted face glistened with

sweat, and his usual mop of carrot-colored hair was plastered

down and dark with it.

"Phew," he muttered to the legs of his boss, sticking out from under a half-dismantled car, "it's hotter than blue blazes."

"Smart guy," a disembodied voice replied. "Tell me something I don't know."

A footfall turned Jack to the door of the garage. Despite the mid-August heat, the man swaggering in was dressed in a tight-waisted suit of big white-and-black checks. He wore spats. A big black cigar protruded from a corner of his thick lips and a brown derby clung magically to the back of his head. His eyes were small, shifty.

"Listen, buddy," he said around the cigar before he was half through the door. "I got a gas engine went haywire on me, in the lot down the block, an' I got to get it fixed up toot sweet or I lose the best Saturday night's business I popped into this season. Can I get a mechanic can fix it?"

"I'm a mechanic," Ransom answered, "but I'm busy here, and besides I don't like the idea of working outside in the sun. It's bad enough—"

"I'll give you an extra fin," the man interrupted, "besides what the job's worth. I'm tellin' you I got to get the damn thing fixed. I'm Dan Hansell, of Hansell's Shows, and that engine's the one runs my merry-go-round and my calliope. Have a heart."

"Go ahead, Jack," the boss called from under the car. "You can stand a little heat for five bucks. It's after five now so you needn't bother coming back till morning."

"All right," the carrot-head grinned. "That sounds better. It'll give me a chance to get washed up early and take Ann and Daphne for a ride in the flivver. I know a spot out Yonkers way where it's cool on the hottest night."

"Yeah," Hansell grunted. "On Central Avenue just before the Grassy Sprain Golf Course. We just come in that way. Come on, if you're coming."

"Wait a minute till I talk my bus into moving out of here."

THE vacant lot was buzzing with activity. A couple of

roustabouts were cleaning it up. There were men stringing

festoons of electric wires. Others were busy fastening together

splintered two-by-fours with winged-nut bolts to make booths, or

erecting a Ferris wheel. Back in the lot were two huge,

tarpaulin-covered vans from one of which more two-by-fours were

being unloaded, and beside them a round, fairly large tent had

been pitched. On the canvas flap that made a door for the tent a

sign said, Office.

Hansell pointed to a single-cylindered gas motor on the ground in front of the office and said, "There she is. When you get her going, holler and I'll come out and pay you."

That, and the way Hansell opened the Office door-flap just enough to let him slide by it—pulling it quickly shut behind him—made Jack wonder why the showman didn't want him to see into it. But it was really none of his business. He looked over the one-lunger, spied what was wrong and got at fixing it.

It wasn't much of a job, and Ransom was through in about fifteen minutes. Just as he was driving home the final screw, he heard a sound from the tent. It wasn't loud, and it didn't come again, but it was very likely a moan—the moan of someone in terrific pain.

The little muscles knotted along Jack's blunt jaw, making a hard ridge. It still wasn't any of his business what was going on in the tent, but Doc Turner, the little druggist on Morris Street, had taught him to make someone else's trouble his business, and it certainly sounded like someone was in trouble inside that tent. It was also certain Hansell didn't want the fact known.

Jack tightened that last screw, got to his feet. A quick glance around showed that the men in the lot were too busy to be watching him. He covered the ground between the engine and the tent in three long strides. An idea had seized him.

"I'm through," he started to say when it was too late for his voice to warn Hansell; he pulled the flap open. A canvas curtain partitioned off a small front space where a bridge-table was strewn with papers, but the canvas was pulled back and Jack saw through the opening. He gasped, going cold all over.

That was the last he knew, for a long time. He hadn't seen the fellow who had come around the tent, behind him, just as he got to the tent. He hardly felt the club that crashed against the back of his skull and smashed darkness into it, and he was not aware at all of the hands that dragged his inert body into Dan Hansell's Office.

GARISH light from high-strung electric globes blazed down

on the pushcarts lining Morris Street. In the harsh glare the

green lettuce heads were brown-streaked and wilted, black spots

dotted the banana hands' bright yellow, and the mounded radishes

were no longer scarlet but filmed by the blue-gray of too quick

decay. Even the piled onions' purplish-green globes shriveled in

the torrid, odorous heat.

A dripping Greek in a dirty white smock frantically scraped the melting ice-block on his white-painted little cart with a rusted metal device, slapped the resultant little balls on paper squares, doused them with virulent green, poisonous orange or sickly pink from his sprinkler-tipped bottles and thrust them into eager, clutching hands.

The other peddlers' undershirts were sweat-pasted to their hairy torsos. Their appeals for patronage were husky, desperate, and without avail. The slow-shifting throngs were not out to spend their paltry pennies tonight. Fleeing the insufferably close heat of the tenement warrens, they gasped now in the insufferably close heat of the street, and they could think only of how hot it was, how unbearably hot.

Dusk had faded into night, but the night brought with it no relief, no faintest stirring of the air that was malodorous with countless stenches of rotting vegetables, of breaths tinctured with pungent, alien condiments, of bodies unwashed, grimy with labor.

The heat underlined the odors of poverty through which the slum-dwellers wandered aimlessly—big-eyed, wan, sweat-dripping, enduring mutely as always the poor must endure.

"The City of Dreadful Night," Andrew Turner murmured, a frail, gray figure in the doorway of his ancient drugstore. "I've stood here more August nights than I care to recall, watching them, and always that phrase runs through my head—the City of Dreadful Night."

"Yes." The voice that answered him was blurred with the fatigue of the long, broiling, sleepless week, but it was cool and sweet and tender. "It is the night that is the worst."

The old druggist's faded blue eyes sought Ann Fawley's face, and the haunting sadness in them was replaced by a sparkle of pride and love.

She was elfin-faced, hazel-eyed, and in the filmy white of her gossamer frock her slim form was fragile, ethereal. One white arm hung lax at her side, the other rested on the shoulder of a sturdy small girl whose black curls were braided for coolness, and whose sharp little features were dark almost to swarthiness.

"Gee, Gran'pa Turner!" little Daphne Papalos exclaimed. "It's awful quiet, ain't it?"

"Isn't, dear," Ann corrected gently. "Not ain't—isn't." Her face was maternal.

A wistful smile touched the thin lips under Doc Turner's bushy white mustache as he looked at those two. About a year ago they had brought the sunshine of youth and affection and love into the lonely winter of his life—Ann, the granddaughter of the maiden he had loved and lost when the world was young and Morris Street an elm-shaded, suburban road; Daphne, orphaned by a nightmare of torture and murder from which the aged pharmacist had rescued her. They were his children, his own.

"Isn't, then," Daphne pouted. "Gee, it's tough to have a schoolteacher for your big sister." Ann was too gay, too young to be called Mother, though she filled the role so well. "Isn't it quiet tonight?"

"Yes, honey," Doc answered. "It is. It's too hot even for them people to talk."

"Listen!" Ann's small head was cocked.

A high-pitched sound, not loud but omnipresent and insistent, underlay the shuffle of weary feet on the pavement, the husky cries of the hucksters, the distant growl of the unsleeping city. It was a thin, shrill wail filling the torrid night.

"What is it?" Ann whispered. "What is it?"

The smile faded from the old man's countenance, and his eyes were bleak, sorrowful. "The babies crying, my dear. The wee babies pillowed on the fire-escapes all around here, or cradled in their mother's arms on tenement stoops, or tossing naked in broken carriages in tenement yards. The babies who have not yet learned to endure their poverty in silence."

An "El" train rattled and banged by overhead, drowning the wail of the babies. When it had passed, a spray of melody came from somewhere, coarse, cacophonous—The music goes round and round. Even softened by distance it was a brassy, unmodulated blare. And it comes out here...

Halfway up the block, someone laughed. Tired people turned, incuriously surprised that anyone could be laughing on an evening like this.

"Doc," Ann's hand grabbed the old man's arm. "What do you call that?"

A head was walking toward them—an enormous bald head. It was amazing. "It's Humpty Dumpty, Gran'pa," Daphne cried. "Out of 'Alice in Wonderland'!"

SCARLET-clothed small legs supported, beneath that

tremendous head, a stocky body the size of a six-year-old's that

was topped by a flaring white stand-up collar, in turn encircled

by a great, vividly emerald bow-tie. Pipe-stem arms, in sleeves

of bright orange silk, twirled two silvery, glittering child's

canes, but these were so miniature that they were negligible. One

was aware only of that monstrous, egg-shaped object moving

through the crowd, of its vast expanse of pallid pink flesh, of

its tiny crimson mouth and flattened nose, its Gargantuan black

eyebrows. The scalp glistened, hairless, in the light from the

pushcart lamps, except where a shining, wee top hat was perched

upon it—a final inspired touch of grotesquery.

You push this valve down—the far-off music blared through the laughter and the little amused screams of the people on Morris Street—and the music goes round and round, and it comes out here.

"Quite a get-up," Doc Turner smiled. "Wonder what he's advertising."

"Hush," Ann hissed. "He's saying something."

The head was nearer now, and they could hear a voice, thin and piping, coming from the tiny mouth that was like a smear of cheap rouge—

"Run, run, come and have fun;

Hansell's circus has come to town.

Fun! Fun! Rush or you'll have none.

Come where the music goes round!"

"Look," the older girl breathed. "Look, Doc. It isn't a mask on a midget. It's a real head. You can see the muscles move in the cheeks, the perspiration streaming down it."

"Everybody come to Hansell's Shows in Hogbund Lane," the head shrilled. "Admission free. Nothing over five cents and a chance to win your fortune. Clowns. A merry-go-round. Ride the Ferris wheel. Play the wheels. Hurry! Hurry! Hurry!"

"Let's go!" Daphne jumped up and down. "Let's go, Ann, Gran'pa Turner!"

"You might as well take her, Ann. It will be pretty tawdry, but it might make you two forget the heat."

"You come along, too, Doc."

"Yes, Gran'pa." Daphne tugged at the old man's coat. "Come with us and have fun."

Doc shook his head. "No, children. I'd like to but I can't. I've got a business to attend to."

THE great head came abreast of the drugstore. It turned.

The dark, beady eyes passed carelessly over the ancient

pharmacist, and found Ann Fawley.

"Here's someone that's coming to Hogbund Lane, folks!" the freak piped. "She's smart and she wants to have fun. Ain't you, babe?" Someone snickered. The tiny, crimson mouth smirked and the silver canes whirled so fast they were two blurred circles. "I'll be there soon's I finish my ballyhoo, an' I'll be lookin' for you." The corners of the beady eyes wrinkled with a smile, but there was no smile in the leering eyes. "Dumpty's my name but I know class when I see it."

The whirling canes flashed, one down, the other up, in glittering arcs across the tiny body. The hands were at the centers of blurred disks again. " 'By, babe," the piping voice said, "I'll be seein' yuh," and then the great head was strutting away down Morris Street, the nucleus of a comet trailing a tail of romping, squealing small boys.

"Come, come, run and have fun..."

the high voice piped, going away—

"If you don't I'm a son of a gun..."

"He is Humpty Dumpty," Daphne squealed. "I knew it. Come on, Ann."

Ann's look sought Doc's, and there was a shudder in it. "No, dear," she said. "We're not going. I've changed my mind."

"Not going?" The child's excited cries were muted. "Not going!" Tears filled her eyes and her upper lip quivered pathetically. "But you said you would. You promised. I want to laugh at the clowns. I want to ride on the merry-go-round. I want to see Mr. Dumpty again. You promised me I could go and this is the first time you broke a promise to me." Daphne turned away from Ann to the white-haired old man who could deny her nothing. "Gran'pa will take me. Won't you, Gran'pa?"

Doc Turner's gnarled, almost transparent hands made a helpless little gesture. "All right, Daphne. I'll take you. I'll go with you and Sister Ann." There was shamefaced apology in the faded eyes that sought Ann Fawley's, and a certain grimness. "I'll take care of you both, and see that you have fun."

Around the corner from Hogbund Lane came the blare of the calliope—oh, ohhh, oh, ohhh, and it comes out here!

FESTOONED bulbs made the vacant lot on Hogbund Lane a

blaze of light shut in between the looming dark walls of two

tenements. A creaking Ferris wheel jerked vertically upward with

its seated buckets of laughing passengers. Rain-streaked, tawdry

bunting did its best to give an appearance of gaiety to open-fronted booths where blue-jowled, shifty-eyed men spun clacking

wheels and raked twenty nickels at a clip into their cash-boxes,

giving in return, to some one of the petty gamblers lined before

their counters, a furbelowed doll or a be-ribboned, flashy box of

candy that would be expensive at ten cents a pound.

On a board platform two clowns, pathetic in tattered, threadbare costumes, capered awkwardly, grimacing paint-widened mouths and contorting chalked faces in which bloodshot, rheumy eyes were glazed and unseeing.

The crowd milled in a feverish imitation of merriment, munching peanuts and pink popcorn, sucking tepid colored liquids through straws, chattering volubly in a dozen foreign tongues. Far back, where only a single light relieved the sultry darkness, two huge, tarpaulin-covered vans lurked, and, beside them, a drab tent was pitched, a crudely lettered placard pinned to its canvas door-flap dignifying it with the title of Office. Ten feet in front of this the chug-chug of a one-cylinder gas engine punctuated the screaming blare of the calliope, and a decrepit procession of wooden animals whirled in an endless round.

Home, home on the range—the brazen, mechanical notes blared—where the deer and the antelope play...

From midway of the lot came the incessant crack-crack of rifles popping at a moving line of cardboard pigeons.

"He was fresh," Ann Fawley whispered to Doc Turner, "but I didn't mind it till I saw his eyes." This was her first opportunity to speak to the old man beyond reach of Daphne's keen ears. "They seemed to be stripping me naked, and there was evil crawling in them, dark and deadly evil."

Where never is heard a discouraging word...

"Suddenly I was afraid of him, terribly afraid."

Daphne waved, skimming by on the back of a camel that had lost its lower lip, her pigtails streaming out behind her, one skinny arm clamped tight about the mutilated beast's neck, her face alight.

"She's having such a good time," Ann exclaimed, waving back to her. "It would have been terrible if she'd been deprived of it because of my silly notion."

"I'm not so sure it is silly," Doc murmured, glancing worriedly about. "I have a queer feeling there's something wrong about this layout. Nothing definite but..." He paused, fumbled for words.

"I know," Ann laid white tapering fingers on his arm. "You've been mixed up so much with the wolves who prey on the very poor, fighting them and beating them, that you've grown to have a sixth sense that warns you of the presence of something crooked, even against all reason. Jack's the same way. There's Daphne again! She's getting an unusually long ride, isn't she?"

"Yes," the pharmacist responded, absently.

"Let's go home when it's finished."

"Mama mia!" a voice screamed from one of the roulette booths. "Eet ees numero seven, my numero, dat de wheel ees stop' on, an' you geeve de can'y to Numero Eight. T'ief! Crook! Figlio di—"

Doc wheeled. A tall, collarless Italian waved excited arms. His pillow-bosomed wife was tugging at his shoulder, screaming, "No! No! Tony!" and the mouth of a bullet-headed little bambino was popping open.

"Wat's dat yuh called me?" the plug-ugly behind the counter grated from the side of his mouth. "Yuh crazy dago!"

"Dago!" Tony screeched. His hand stabbed into his pocket, snatched out a knife whose blade snapped open at a flick of his wrist. "You rob me an' then you eensult me!"

"Stop it, Tony." Somehow, Doc's small form had covered the distance between before anyone else had taken a single step. "Put that knife away. Put it away, you fool!"

The Italian's hand wavered, dropped to the counter. "He cheata me, Doc," he said flatly. "An' then he calla me 'dago'."

"All of which is no excuse for pulling a knife on him," Turner chided the man, as he was accustomed to chide all the bewildered aliens whose only friend he was. "Besides, you called him names first." From the corner of his eye he saw the concessionaire's hand fall from the pocket where a long, flat lump betrayed what it was he had reached for. "Apologize to him for that, and he'll take the 'dago' back, and then we'll get the argument settled..."

THE crowd, surging in about the dispute, hid Doc from Ann

Fawley. She started to go after him, recalled Daphne, turned back

to the carrousel. The camel without a lip came around once more.

An unseen hand clutched Ann's throat. That was the camel

for which she was watching—no doubt of it—but no small form

rode astride it now. The merry-go-round had not slowed at all,

but her little adopted sister was gone from the camel.

"Daphne!" Ann called. Her throat was so tight that it was a mere husk of sound, inaudible above the calliope's screech. Home, home on the range...

"What's the matter, babe?" a piping voice said in her ear. "Yuh look sick." It was the head—the freak with the tremendous head. "Kin I do somethin' for you?"

The girl's revulsion was forgotten in her anxiety. "She's gone, Mr. Dumpty. My little sister. She was riding on that camel and now she's gone."

"Oh," the little mouth smirked. "Is that your sister? She fell off the other side, an' they took her in the office. She ain't bad hurt, but—"

"Take me to her! Take me to her at once."

"Sure, babe. It's a pleasure. Come on, it's round back o' the carrousel, here."

TONY grudgingly apologized for his epithet, and the man

behind the counter as grudgingly retracted his. Doc exchanged a

quarter for a flat box tied with gilt ribbon, that mercifully

obscured most of the startlingly-colored chromo imprinted on

pale-blue glazed paper, and the bambino clutched it happily.

"Give him a good dose of castor oil," the druggist admonished the volubly grateful mother, "before you put him to bed. The quicker that junk is cleaned out of his system the better."

The crowd scattered. Doc went back toward the carrousel.

Neither Ann nor Daphne were in evidence. "They should have waited here for me," Doc muttered. "How do they expect me to find them in the crowd?" He turned away, his old eyes searching the milling mob without result, and started slowly toward the entrance.

He was greeted by a long-bearded patriarch from whose hand a black-haired little tike dangled, whimpering because molasses-covered popcorn was forbidden to him by the dietary laws. Doc bought the tiny child a great green balloon.

"Buy me one, too, Mister Turner," begged a tot clad in a too short pinafore and nothing else, angelic curls clustering about a face that dirt made anything but angelic. "I just spent the nickel Mom give me on the mewwy-go-wound an' I ain't got no more money."

"Here you are, Carlotta. Did you like your ride?"

"Sure. I was on a elfunt. Didn't you see me? I was ridin' right behind Miss Fawley's little sister."

"So you were right behind Daphne? Did you happen to see which way she and Miss Fawley went when the carrousel stopped?"

"She wasn't on the mewwy-go-wound no more when it stopped. She went away with Humpty Dumpty." Her eyes glowed.

A pulse throbbed in Doc's wrist, but he kept smiling and there was no change in his smiling, kindly voice. "How did she get off when it was going so fast?"

"The man what takes the tickets lifted her off. Humpty Dumpty was standing there by the thing that goes puff-puff, and Miss Fawley's sister hollered out to him 'Hello Mr. Dumpty' evwy time we passed him. Then one time he hollered out 'Do you want to go see Tweedle-Dum?' She said 'Yes', an' the ticket man lifted her off on to the gwound. The next time I came awound she was just going into the wigwam in back with Mr. Dumpty."

The sultry, breathless heat lay close against the old druggist's body, and, somehow, he could not draw it into his lungs.

"Spend your nickels, spend your dimes!" sounded, high-pitched and thin, in his ears. "Forget it's hot and you'll have good times!"

A great pink head swam out of the whirling chaos, its glistening scalp topped ludicrously by a gleaming little silk hat.

"Mr. Dumpty, Mr. Dumpty," little Carlotta's voice clamored. "Kin I see Tweedle-Dum, too?"

Doc's fingers caught a bony shoulder under a sweat-wet pinafore sleeve. "Run along home, Carlotta!" he heard his own voice say sharply. "Run home." And then he was talking to the head. "What have you done with her?" he was saying. "What have you done with my little Daphne?"

The small red mouth simpered in the vast face. "I don't get yuh, guy. Who's Daphne?"

Alice in Wonderland—the calliope blared, hammering at Doc's skull—Come let me take your hand...

"Take it easy," a new voice grunted, beside Turner. The man stood close against Doc and something hard jabbed into the druggist's side. "Take it easy, buddy." The low words came from the corner of thick lips that were clenched on a big black cigar. The man had on a loud-checkered suit and a brown derby clung magically to the back of his close-cropped head.

"Yeah," Dumpty piped on the other side of Doc. "An' don't go getting no ideas that Dan'll be scared to bump you right here in this mob. His roscoe's loaded with .22 rifle bullets like the guns over in the shootin' gallery. They're little but one of them'll lay you as cold as a .45 slug, and it'll look like one of them rifle pellets bounced off'n a target and hit you."

You'll see the Wonders pass, looking through the Looking Glass...

"You'll be all right," Dan said, "if you just come along nice with me and talk it over in my office. But one yip out of you— "

Doc Turner's aged body was a tight, icy shell within the torrid heat. His seamed countenance was mask-like, devoid of all expression, but behind it a keen brain that had met uncounted threats, and defeated them, was no longer blurred.

"What do you say, guy?" Dan demanded. "Going to behave?"

Right there before your eyes, I'll show you. Paradise...

Doc shrugged. "I haven't got much choice, have I?"

"Walk along then, back towards the tents with me, and make believe you like it."

THE two started off. Of the hundreds of eyes all about,

none turned toward them. A clown was spinning over and over—

hands, feet, hands, feet—in an incredible pinwheel on the

platform centering the lot, and no one had any attention to spare

for anything else.

"Watch him twist, watch him spin," Humpty Dumpty enjoined, unnecessarily. "Then play the wheels and you're sure to win."

They went past the whirling merry-go-round. So let me take your hand, the calliope shrieked. They went past it and into the darkness beyond it. The chug-chug of the little gas engine chuffed through its Alice in Wonderland.

To what infernal wonderland had they taken Daphne? What did they want of the child, what dreadful thing? And Ann! They must have gotten hold of Ann, too, otherwise surely she would have been searching for him now, surely have found him.

"Have your fun, everyone;

It's getting late, soon all will be done."

Doc made for the canvas door flap on which hung the sign, Office, but the gun in his side prodded him to the left, past the tent, behind it.

Something moved in the darkness, a blacker bulk against the black. Hands seized Doc, calloused hands, cruel and rough. An involuntary exclamation was stifled in his throat by a rag shoved into it, and then the hands were jerking his arms behind him, binding their wrists.

The man in the checked suit laughed, keeping the sound of it down. The merry-go-round yowled, its time and key changing: Look at the Mad Hatter laughing there. The old pharmacist's ankles felt cruel thongs dig into them, lashing them.

"Good work, Carl," Dan's voice said. "Now stick him in the storage tent."

Doc was shoved along the ground by a hard boot. He felt canvas scrape his face and then he was in some hot, close chamber.

While Tweedle-Dum and Tweedle-Dee are... ARRGH... the calliope ran down.

The stopping of that blare left a throbbing silence that gradually filled with the distant, muted murmur of the crowd, the crack of the rifles in the shooting gallery, the creak of the Ferris wheel. Doc became aware of a sound closer at hand, very close, the sound of heavy, stertorous breathing. He was not alone!

Was it Ann? The breathing seemed too heavy, too coarse, for hers. His pupils were accommodating themselves to the darkness. It wasn't entirely black in here any longer. Some light seeped through the cracked roof, so that he could make out the narrow, canvas-curtained space of his prison. Vague shapes were forming out of the dimness. Irregular shapes.

The old man made them out as piles of folded bunting, as a stack of gallon cans. The pungent odor of turpentine told him that one of them at least must be open, and that it was a can of paint... He made out another shape, the shape of an outstretched body.

Doc Turner knew who lay there, bound and gagged. It was Jack Ransom! Jack, the youth who had been his good right hand in so many battles against the underworld. Jack, Ann Fawley's sweetheart!

IT was light enough now for Doc to see Jack's staring blue

eyes, fixed on his face. They were signaling to him, moving from

him to the canvas that formed the back wall of this space where

they lay tied, moving back to him and then again to the curtain.

Jack was trying to tell him something.

The old man squirmed laboriously across the ground. Little stones embedded in it tore his palms, gashed his cheek, but he managed to get to the canvas. By pushing his head against it he lifted it a bit, peered through underneath it.

Chug, the single cylinder engine outside started again. Chug-chug. A child laughed happily, and then the calliope took up where it had left off...

The old man was looking hard, but he could see only another black canvas wall, six feet from the one under which he was peering, and between them queer forms whose nature he could not make out.

"All right, all right," Humpty Dumpty's piping voice said, beyond that farther canvas. "Keep your shirt on. I got it all figured out." The canvas was abruptly yellow with a light that had come on behind it, and the black shadow of an enormous head moved grotesquely across it.

"Maybe you got it all figured out," Dan was saying, "but I don't like it. Pulling this sort of stuff is all right in the hick towns, but its hell and all in the city."

Doc's heart was pounding against his frail chest. He could make out now the cot on which Ann and Daphne lay, bound and gagged, but that was not what widened his eyes with horror.

"It was you had that bozo from the garage conked, wasn't it?"

"Yeah. I hadda do that after he piked off what we got in here, but that ain't messing things up like you done."

A glass jar, two feet high, stood in the center of the space between the two curtains. Projecting from its top the head of a little boy lolled, eyes closed in a weary sleep the agony which lined the blood-engorged face could not stave off. That head was too large for the body that was clamped inside the jar, that was enclosed naked within its glass so that it might be stunted while the head grew larger, and larger! It was a freak in the making at which the old druggist stared, a freak...

"Hell," Dumpty piped, "the old guy will be just as easy to get rid of as the other."

"An' the brat—"

"We been carrying Jimmy all around the country without him being piked off, ain't we? We'll carry her around the same way. Listen, Hansell! We figure we stand to make plenty out of Jimmy when he's ready, don't we? Well, what do you think we'll make out of a couple like him, a boy and a girl?"

Sick horror crawled in Doc Turner.

"Well, maybe you're right about that, but we got to bump off the dame with the two guys. She ain't no good to us."

"She may be no good to you, Hansell, but she is to me. Cripes, I'm a man ain't I, even if I am a freak. I'm damn tired of watching everybody else with their women and me only being laughed at. I've got my woman now!"

The old pharmacist lay weltering in black despair. From outside came the blare of the calliope, mocking him. Right there before your eyes, I'll show you Paradise...

Right there, before your eyes, was Hell.

"Well," Hansell was saying, "I guess there ain't no use arguing with you. We're in it now, hide, stock and barrel. We got to get going pretty soon. I'll tell Carl to slit the guy's throat."

"And have blood all over the ground and two corpses to get rid of, with everybody knowing the old man came here and didn't go away? That's like you, Hansell, dumber than hell."

"I suppose you got somethin' better worked out."

"Sure thing. It's going on right now. They're going to be found in the young guy's flivver, that we got parked behind our trucks, and they're going to be deader than hell, but not with lead or a shiv. The winders are going to be closed, and they're going to be blue and cold."

"What the hell—"

"Sure. 'Jever hear of guys passing out in the cars, Hansell? I had Carl hitch a hose to the exhaust of the one-lunger and stick its other end into the tent back there, under that pile of paint cans where they can't get at it. He's watching out back with his shiv, case they catch wise and crawl out, but there ain't much chance of that. Meantime, that pipe's pumping carbon monoxide-gas in there..."

Doc knew now why his head throbbed with agony, why his brain was whirling.

"That's why I called you in here. We got to get the kids and the dame out of here before they get it, too."

Doc's eyes were hard glints of light as he listened.

THE piping voice blurred. Doc was conscious now only of the sick giddiness within his skull, the fierce pain across his eyes, and of the chug-chug, of the engine whose every revolution vomited lethal fumes into his death-chamber.

You push this top valve down—chug—and the music goes round and round. There was a way—there was some way to fight the fumes. Somewhere in here. That smell, that stinging smell—not carbon monoxide, carbon monoxide has no smell... It was the paint that he smelled!

And comes out here. Paint! Turpentine and zinc oxide or lead oxide. If it was only white paint, that was open, then he—

"Whee! We're getting some ride!" a childish voice cried. "A long one." Chug. A long ride for you, son, and a long ride for Jack and me. A ride to hell.

Doc was crawling, crawling through whirling darkness, through a dizzy maelstrom of pain, toward the stack of paint cans. Sometime in that crawl he had gotten a tag-end of bunting caught in his teeth, and he was dragging it after him.

The can—the open can—was swimming in front of his eyes. The dribbles down its sides—Doc squinted, trying to see—were, yes, they were white... And never is heard—chug—

Doc butted over the can with his head. The white paint gushed out, over his face, soaking the bunting. Outside, the calliope played and the children shrieked with the joy of their long, long ride, and the engine chugged, chugged, while, within that tent, a frail old man squirmed, haltingly, feebly, across the ground to where a redheaded youth lay pale and white and dreadfully still. The old man got to Jack at last, pulled the paint-soaked bunting over his face with his teeth, and dropped alongside of him.

THE dreadful heat still lay over Morris Street, close and

choking, though it was long past midnight. The wail of the

sleepless babies still filled the night, not loud, but high-pitched and persistent. The lot on Hogbund Lane was dark now, the

festooned lights down, the booths struck, the merry-go-round and

the Ferris wheel dismantled.

"Carl and Dumpty and me will strike the office tent and load it," Dan Hansell mumbled around his cigar to the crew crowding around him. "We want to get to Trenton and get set up before the folks start going to church."

"All right, guys," Hansell said to the two who were left with him. "Guess the tent's aired out enough now. We'll get rid of the stiffs and be on our way."

Carl lifted the back wall of the office tent, and the man with the big head ducked under it. He went into the darkness...

A whirling something swept his tiny body from under him. He had time only for a single shrill scream before that tremendous head of his crashed on the ground and a desperate elbow pounded it.

"What—" Dan Hansell gulped, thrusting into the tent space. Two forms hit his knees, pounded him to the ground, swarmed all over him. A hard skull crashed against his jaw and he lost all interest in the proceedings.

Carl had his knife out, but there was no one to hold up the canvas for him so he had to get down on hands and knees to crawl under it. That was his undoing. Two heels, bound together but still capable of dealing a sledge-hammer blow, crashed against the nape of his neck. The wind went out of him and he collapsed.

His fist clutched the knife firmly, even in his unconsciousness—firmly enough at least for Jack to slide his bound wrists along its edge and slice their lashings. It was the work of a minute then to free his ankles, to dig the gag out of his mouth and go to work on Doc Turner.

"That was the tightest squeeze we been in yet," he husked as he cut away the old man's thongs. "I didn't think we'd get out of it this time, and I still don't know how you managed it. What was the idea of the paint?"

Doc had to use his fingers to pry his lips apart, stuck together as they were with the pigment, that was not white but queerly gray now. "Zinc oxide or lead oxide," he explained, "make the turps white. Carbon monoxide is a strong reducing agent. We breathed it through the paint, and it took the oxygen out of the paint and became carbon dioxide which is harmless. This stuff is grey now because it's metallic zinc or lead, instead of the oxide."

A WHITE-COATED ambulance doctor said, "The boy is not

irreparably injured. With proper care, he'll grow up normally.

How're you, sister? Get over your scare?"

"I wasn't scared," little Daphne boasted. "I knew Gran'pa wouldn't let Humpty Dumpty hurt me. But I'm not ever going to read 'Alice in Wonderland' again."

"Yes, you are," Doc said softly. "Yes, you are, honey. Because that wasn't the real Humpty Dumpty. He was only a bad gnome that dressed himself up in Humpty Dumpty's skin like the wolf dressed himself in Red Riding Hood's clothes."

Ann didn't hear Daphne. It didn't seem to make any difference to her lips that the lips against which they pressed were sticky with paint, or that the arms around her were black with grease and sweat.