RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

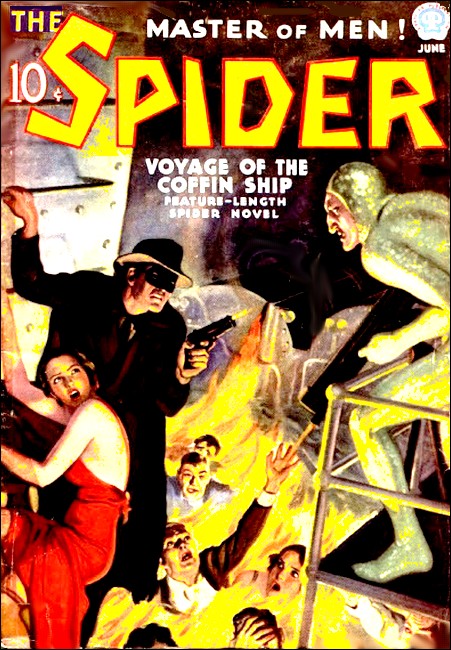

The Spider, June 1937, with "Doc Turner's Subway Suicide"

One deadly bullet threatened grimy diggers with racket slavery—and shoved Paul Melwin into the shadow of the chair. Then Doc Turner took up the murder hunt where the police left off.

IN the past week a new odor had been added to the conglomerate stenches of Morris Street. It mingled with the tart-sweet smells of the fruit piled high on the pushcarts lining the bustling slum thoroughfare. It overlaid the aroma of rotting debris; of unwashed sweaty bodies; of breath insistently redolent with the memory of alien foods. The salt tang of the muddy River to the East was tainted with it. It seeped through the grimy tenement windows, finding the chinks between their warped frames and paintless sashes. It drowned the spicy fragrance of old herbs, of esoteric tinctures and fluid extracts in Andrew Turner's drugstore.

Through the pervading fetor was that of illuminating gas, it came from no leak in a main. It was exuded from the black-brown, crumbling earth walling the trench, narrow and deep as a grave, that bordered the curb of Hogbund Lane from the corner of Morris Street to the River.

Andrew Turner, his frail form a little stooped with age and the weariness of the long years, lounged before the big window of his pharmacy and watched the rhythmic rise and fall of overalled, muscled shoulders in and out of the long gut, the cadenced gushing of dirt from skillful shovels. A vagrant breeze stroked his silky-white mane. His gnarled fingers tugged at his drooping mustache, and his bushy brows did not hide the brooding worry in his faded blue eyes.

A honking stream of traffic thundered West on Hogbund Lane. Florid-faced, sweating, the drivers of canvas-covered lorries carrying produce from the riverside warehouses swore at slab-sided trucks stationed beside the trench to receive dirt from flying shovels. The square-jawed chauffeurs of the dirt trucks swore back at them. The air was sulphurous with profanity, but there was no rancor in the bandied epithets. Why should there be? Everyone was happy in the knowledge that this Friday night, and every Friday night, there would be money for corned-beef and cabbage, for pasta and ravioli, for gefilte fish and blintzes. The depression was still too close for these sweating sons of toil to have forgotten the dreary, mind-wrecking days of 'on the relief.'

A shiny black limousine was as incongruous in that clamorous procession as a man in top hat and tails would have been in the trench. Its sleek hood nosed into a space between two of the dirt-filled trucks and its fat tires whispered to a halt. Before the liveried driver could move the limousine's back door opened and Paul Melwin leaned out.

"Hi, Doc," Melwin called. "What's good for heartburn?"

Doc Turner smiled a little, going toward him across the sidewalk. "Try eating potato bread and onions and cabbage soup for a while, instead of poulet à la Française and pommes de terre à la holcha. You had no heartburn when you were Pavel Melwiczn, with no seat in your pants and no idea of where your next meal was coming from." The old druggist had no awe of the wealthy contractor for whom these men and a thousand others labored. Melwin was just one of the Morris Street boys to him. One of his children.

"I get you, Doc." A rueful grin creased the other's heavy-jowled, broadly sculptured countenance. "But there ain't no—isn't any—use ribbing me. I may be boss here, but Ida is double boss on Garden Avenue." He heaved out of his car, over the trench, his burly frame compact with lithe strength for all the custom-tailored Harris Tweed suit that clothed it. "She makes me keep my coat and shoes on even when we're alone together."

"You—"

"Listen, Mr. Melwin." The voice that interrupted Doc was mellifluous with Latin softness, its syllables tinged with an unmistakably foreign accent though there was no mispronunciation of its English. "I was just going to your office. Your Super's put on a half dozen new men this morning. How about it?"

"Well, how about it, Liscio?" The good nature vanished from the contractor's face as he swung to the speaker. "They're union men, aren't they? What's your kick?"

"They ain't from Local Forty-six." Pietro Liscio was slim, dapper in a navy-blue suit. His thin-cheeked face was sallow, its native swarthiness faded. "If you don't throw 'em off the job I'll have to pull a strike on you. We won't work with no scabs."

"If I fire those diggers you won't work at all. Rafferty will call his teamsters out. I won't be able to haul the dirt away and I won't be able to get the pipe up here." Melwin was low-toned, slow-spoken, but his face was purpling. "Those six men are no skin off your nose. They're on the same pay and hours as your crowd. Union pay and union hours. The only difference is they've got Local Nine on their cards instead of Local Forty-six."

The nostrils of Doc's bony nose flared a little. He had a queer notion that the gas-smell was heavier, so heavy that a striking match, a spark from one of the shovels clicking against a granite cobble would explode it into a catastrophic outburst of flaring destruction.

"THAT'S too much difference," Liscio was saying. "This is

Forty-six territory and Nine's got no call muscling in on

it."

The contractor's thick neck corded, the top of his white collar cutting into it. "That's racket language," he said quietly. " 'Muscling in'."

"That's just what Rafferty is," the union man came back. "A racketeer. His laborers' local is a racket and his teamsters' union is worse. He's in the game for what he can get out of it. What's he getting from you? What's he promised you? A new agreement when he's smashed me and my bunch?"

Melwin's big paw darted out. Its spatulate fingers fastened on Liscio's coat collar, tightened. Though the union man's feet were still on the sidewalk he seemed to be hanging from that hairy fist.

"Playing with him, am I?" the big man bellowed. "You're a lying dog, Pietro Liscio, and you know it."

Backs were no longer rising and falling in the ditch. Shovels were motionless. Swarthy, mud-streaked faces were attentive, straining to hear, straining to see. Blue-jawed, simian-armed truck drivers were drifting, carefully casual, toward the black sedan. One of them hastened his pace, reached the corner and went into Doc's store. His nickel, dropping into a telephone booth, pinged sharply through the traffic sounds, through the raucous shouts of the hucksters and the shrill chaffer of shawled housewives that made a murmurous background for Paul Melwin's thick-tongued roar.

"Listen, you whelp!" he shouted, shoving the palm of his free hand within an inch of Liscio's face. "See them calluses? I got them swingin' picks in ditches like that." He turned the hand, jabbed a thick thumb at a scar on the ridge of his jaw. "See that? That was made by a fink's brass knuckle, in the first laborers' strike ever pulled. I ain't forgot I once swung a pick, an' I ain't forgot the guys I worked with and fought for. You got any squeal about conditions on my jobs?"

"No," Liscio whispered. "No."

"Damn right you haven't. Everybody knows I give my men all that's coming to them and a hell of a lot more. Everybody knows that when the city was busted I took its contracts anyway and laid out my own money to keep a couple hundred slobs from starving, not knowing if I'd ever get paid back. Everybody knows it was me who rammed the union down the Contractors Association's throat when men was crawlin' for work at any price. Everybody knows I'm the best friend the working man ever had in this town. That right?"

"Sure. I got nothing against you. This is a jurisdictional dispute and..."

"And you'll leave me and my jobs out of it if you know what's best for you. I've been trying to get along with rats like you and Pat Rafferty to save the poor dumbbells you've got fooled from getting hurt, but I'm through now. I've fought too hard and too long to get where I am and I'm not letting a dog like you drag me down again. Try it and I'll smash you out of my way. Like this!"

The arm that held Liscio straightened, flung him across the sidewalk to sprawl upright against a rain-streaked tenement wall. The fellow clung there, hate in eyes that were glittering black beads in a pallid face, lips curling away from pointed, uneven teeth.

"All right, Melwin," the low words came from between those teeth. "For that I change my demands. If there's anyone but a Local Forty-six digger turning dirt on any of your jobs tomorrow morning I'll strike every one of them."

"Strike and be damned."

"You're thinking Rafferty will help you, but he can't. He can't give you enough men to carry your jobs through anywhere near contract time. The forfeits will bankrupt you and the Contractors Association will see that they're claimed. I'll finish you and Rafferty together."

"You'll finish Rafferty all right. The minute trouble starts every union man on my pay-roll gets fired, Nine or Forty-six or any other damn number. I've never hired a scab in my life but I know where to get them, and I know where to get guards to protect them, too." Melwin's voice was a defiant growl. Doc Turner was the only one near enough to see the almost unnoticeable quiver of his ridged jaw, the twitch of a muscle in his cheek. "Try it and see what happens to you." Doc was the only one to see the big man's fist closing at his side, slowly, very slowly, as if its shaggy fingers were tightening on someone's neck, savoring the feel of flesh squashing under them, of gristle crumpling. "If you've got guts enough."

Paul Melwin turned on his heel, sprang across the ditch and into the limousine. The door slammed and the black car surged away.

Pietro Liscio pushed himself away from the wall. "Everybody down at Union Hall tonight," he called to the shovellers. "Pass the word along."

DOC TURNER found himself a seat under the balcony of Union

Hall on Morris Street. He had kept his coat collar up, his hat

pulled down over his face, as he had shoved in with the crowd,

and nobody had recognized him. He was safe enough from being

spotted. The illumination from the few fly-specked electric light

bulbs scarcely reached here, and the close-seated, jostling crowd

had eyes only for the table at the other end of the big room,

where, under an American flag draped on the scabrous wall, sat

Pietro Liscio, president and dictator of Local Number Forty-Six,

International Union of Laborers.

"Gee, Doc," a carrot-headed, burly youth seated next to him muttered. "I don't get the idea of your shutting up shop and coming here at all."

"I had a funny idea that it's more important for me to be here than in my store," the old pharmacist murmured. "But this is no place to talk. Just keep your eyes and ears open and your mouth shut."

"Wish I could keep my nose shut too," Jack Ransom grumbled. This barrel-chested young man was Doc's constant companion on his forays against the wolves who prey on the helpless poor; his good right hand—or rather fist. "I hate the smell of garlic."

"Hush." There was a stir at the door, some ten feet from where the two sat. Someone was trying to shut it, fruitlessly because a knot of late comers remained obdurately within the opening.

"Let it go, Tony," Liscio called. "If Melwin's got any spies out there or in the hall he's welcome to what they can hear." He sipped some water from a glass on the table, stood up. "All right, everybody. Quiet."

The polyglot chatter that had filled the chamber died down. Liscio leaned forward against the table, his palms flat on it.

"I'm glad to see this mob here," he began, "because it means you're not letting Paul Melwin's gorillas scare you any more than he scared me this afternoon. You fellows on the Hogbund Lane sewer saw and heard what happened, and I know you've told the rest. You heard him threaten to smash me, and you know that if I go, Pat Rafferty will step in and take the Local over like he took Local Nine over. But you don't have to wait for that. If you'd rather have Rafferty in charge I'll resign right now and turn the books over to him. You know what kind of deal he'll give you, but if you want it that's all right with me. How about it? Do I resign?"

"No!" Walls and ceilings seemed to bulge with the thunder from five hundred throats. "No! Hooray fer Liscio! Viva Pietro! Liscio! Liscio!"

Listening to the tumult of those huzzahs, a saturnine smile tipped Pietro Liscio's thin lips. He lifted a hand from the table...

A look of surprise crossed his dark face. There was, curiously a third eye, a scarlet eye, between his black ones. He swayed forward, dropped across the table, rolled from it to the floor.

A gasping, ghastly silence thudded against deafened ears, too late to let the sound of the fatal shot be heard. For an infinitely long moment there was no movement in the hall except where a broad-shouldered, carrot-headed youth was throwing himself in a bull-like rush through the standees about the door.

Jack spurted out of the massed bodies into the corridor outside. He saw a chair standing against its rear wall, heard the thump of running footfalls from the stairwell. Before he could turn to it a door slammed, far below, and there was silence.

Silence in the corridor, on the stairway, but pandemonium within the meeting room. Shouts, screams, a pandemonium such as only a zoo can give forth, or a hall full of terrified, excited aliens.

"Liscio's dead," Doc Turner's quiet voice said to Jack. "Killed instantly. There will be no strike tomorrow."

"I got out here too late," the youth groaned. "I saw the flash but by the time I got through, the killer was in the street and there wasn't any use chasing him. Never pick him out of the mob down there. He stood on that chair and shot over the heads of the crowd."

"Yes," Doc answered, his calmness curiously accentuated by the turmoil within. "There's his gun." He pointed to a dull-blue automatic beneath the chair.

"Gosh!" Jack bent, reached for it. Doc's fingers on his shoulders jerked him back.

"You fool!" the old man exclaimed. "Leave it alone. Chase down and call the cops."

THE sun filtered through the trestle of the "El" and made

a pattern of warm light and cold shadow on the cobbled gutter of

Morris Street. It was too early for the pushcarts to be out.

Inside Doc Turner's drugstore the musty closeness of the night

had not yet been dissipated by the morning breeze that crept in

through the door, bringing with it the chug, chug of delving

spades.

The smell of gas was very heavy in the store.

Turner hung up his shabby overcoat on its hook in the back room, turned to the sound of thumping footfalls. He pushed through the grime-stiffened curtain that closed off the opening in the partition dividing the prescription sanctum from the front of the store, saw that his early caller was Jack Ransom.

"Here's the paper, Doc!" Jack called, coming back toward him. "The cops are sure working quick on that killing last night." He reached the sales counter that paralleled the partition, slapped an inky sheaf of sheets down upon it "Look at this."

The white-haired druggist stared at black, screaming headlines. His seamed face went gray as he read them, his eyes cold and very bleak:

CONTRACTOR NAMED IN LABOR SLAYING

PIETRO LISCIO SHOT WITH MELWIN'S GUN

SEWER BUILDER HIDES

There was an account of what had occurred in Union Hall, as

accurate as might be expected. There was a paragraph telling of

the argument on Hogbund Lane. In cold type Melwin's

defiance—"Try it and see what happens to you!"—was

unmistakably a threat. And then there was this:

Experts of the Ballistics Bureau have determined that the bullet in Liscio's brain was fired from an automatic discovered under a chair in the corridor of Union Hall, upon which the slayer must have stood in order to fire over the heads of the crowd. The killer had wiped all fingerprints from the gun, and the number of the weapon had been filed away. However, the Police Research Laboratory was quickly able to raise this number again, by the use of acids and polarized light, and the records of pistol permits at Headquarters revealed it to have been purchased by Paul Melwin.

Mr. Melwin had previously been interviewed at his duplex apartment on Garden Avenue, having been called out from a formal dinner party for this purpose, and had denied all knowledge of the murder. Upon receiving the report of definite tie-up between the contractor and the lethal weapon, Captain Forster of the Homicide Squad issued orders to bring him in for further questioning. It was then disclosed that Melwin had left for Asbury Park at midnight and was already out of the state. A long distance telephone call to him elicited a refusal to return to this city.

"I got my lawyer here with me," Melwin told Captain Forster, "and he advises me not to come back. He says you got no evidence I have anything to do with Liscio's death, and my doctor ordered me away for a rest. My health demands I stay here, and you can't extradite me as a material witness. If the Grand Jury indicts me I'll surrender."

"Maybe that will happen too," the police officer warned. "You've got an alibi all right, but the gun is yours. You could have given it to a hired thug, you know, and the Grand Jury is likely to think so."

"I haven't seen that gun for weeks. I stuck it in a desk drawer in my office right after I bought it and forgot all about it."

The district attorney's office is reviewing the law to determine if there is not some way of extraditing Melwin. Meantime the police are searching for the actual assassin, and...."

Doc's reading was interrupted by a rustle of skirts. His

expression took on the genial, interested smile with which he was

accustomed to greet his customers, and he looked up from the

newspaper. The woman was no denizen of Morris Street, not only in

a redingote coat of soft, silky wool that could have been

fashioned only by Molyneux, in a chic small hat pertly and

unmistakably Parisian. But dexterously applied powder and pastel

shaded rouge could not hide the distress in her face, the agony

in her eyes.

"Ida!" the old pharmacist exclaimed. "Ida Gorchik!"

Her lips quivered. "Ida Melwin, Doc. Have you forgotten?" Her slightly too red lips quivered a bit. "But maybe it is as Ida Gorchik I come to you, like I used to come years ago when I was in trouble."

"When your doll was broken, and later when you started going with boys and your old mother wouldn't let you stay out after nine." Doc's voice was very gentle. "No, Ida. It's you who forgot me, and Morris Street when you moved away to Garden Avenue."

"I know, Doc. There is so much I could have done for those I left behind. I don't deserve anything from you. I don't deserve your help. If it was for me I wouldn't come to ask you for it. It's for Paul. He didn't forget them. He's fought for them all his life. And now they're cursing him out there. I heard them. They're saying he's a murderer. He isn't, Doc. You know he isn't. You'll help him prove he isn't, won't you?" Her gloved hands came out to the old man in a pathetically appealing gesture. "You'll help my Paul."

"He has his lawyers, hasn't he? And they told him to run away."

"I told him to run away. I couldn't bear the thought of Paul in a cell, of Paul being tortured by the third degree. I made him go away."

"Samson had his Delilah too," Doc muttered. Then, "They would have questioned him, but they would not have arrested him and they would not have given him the third degree. Now they will. He can't come back now, and Rafferty will have his chance to take over the Union. He'll sell them out to the Contractors' Association like he sold out the Teamsters. Everything that Paul built up will be torn down, destroyed. I'm sorry for Paul, but I'm infinitely more sorry for those workmen outside, for what's going to happen to them. For their families, who were beginning to see a little light in the night of hunger and exploitation, and who will see that light blink out now, perhaps forever."

Curiously enough, Ida Melwin's eyes brightened. "You will help Paul then!" she exclaimed. "You will prove he's not guilty of murder!"

Doc's smile was a little bitter. "How well you know me," he murmured. "Yes. I'll do my best. Not for you, Ida Gorchik, who have done your best to forget that your father once stood long hours behind a pushcart out there. For your husband, who did not forget he once swung a pick. For the bewildered aliens who still wet the handles of their shovels with sweat, who still drag out their dreary hopeless lives in the teeming tenements from which you escaped through no virtue of your own. Go home, Ida, and think how many mouths you could have fed with the money you lavished on the dinner last night that supplied Paul with an alibi that might prove worthless. Think how many children you might have given a week in the country with what you spent on that Newport 'cottage' of yours last year. Go home."

She was gone. The faint scent of her perfume lasted only an instant, and then was vanquished by the smell of poverty that lies on Morris Street like a pall, by the smell of gas exuded from crumbling, brown black earth.

DOC looked ruefully at his friend. "I'm getting wordy,

son. That's a sure sign of old age."

"You're saying Melwin wasn't behind that killing is a surer sign."

"No. I know Paul had nothing to do with it."

"Why?"

"I've known him since he was a dirty-faced brat running around these streets. He was always fighting, but he always fought fair."

"That's sure a clincher. Why don't you tell it to the cops?"

"Perhaps I'll have something else to tell them before long. Perhaps..." Doc broke off. "Get into the back room," he snapped. "Quick!"

Jack dived past the counter. The curtain had scarcely stopped swaying when the shadow that had fallen across the store's threshold solidified into a man's form. The fellow who came in swung heavy shoulders, the half-bent arms hung from them sleeved by a pattern of loud checks. His brown derby was shoved back on a bullet head and his gross lips mouthed a plump cigar.

"Yuh're Doc Turner, aincha?" he growled, pounding toward the sales counter. " 'Nosy' Turner."

Doc arched his bushy white eyebrows quizzically. "I am Andrew Turner," he responded evenly. "What can I do for you?"

"Yuh can take yuhr beak out of my affairs, that's what." Reaching the counter, the newcomer thrust his face over it, the cigar almost touching Doc's cheek.

"I'm afraid I don't know either you, or what you mean." The druggist didn't move from his stance, his countenance expressionless.

"I'm Pat Rafferty. Yuh damn well know that, and yuh damn well know I mean yuh got them wops and yids what's workin' for Melwin haywire. Here I send my organizers to sign 'em up for Local Nine, now that Liscio's ice an' his Forty-six busted up, an' all the boys hear is, 'Go aska Docca Toiner. If Docca Toiner say all right we join. Odderwise, no.' What the hell is this anyway? You their padrone?"

Turner's smile had no humor. "No. I'm not their overlord. But they trust me. I circled around last night, after Liscio was killed, and whispered to them to send you to me when you showed up this morning, and to do nothing about joining your local till I gave the word it was all right. When Doc Turner asks something around Morris Street it's usually done."

"Oh yeah?" Tiny red lights crawled in Rafferty's small eyes. "Well, yuh better learn that when Pat Rafferty wants some-thin' anywhere in this man's town he always gets it. He's got ways uh gettin' it without askin'."

The old druggist sighed, "So I understand. Ways like—murder, for instance."

Rafferty's cigar fell to the counter in a shower of sparks, its end bitten through by suddenly clenched teeth. He spat the remnant past Doc, and his fingers dug into the edge of the worn wood, as if to break it off.

"Why, yuh old—" he blurted. "Yuh're nuts!"

"Perhaps I am." Not a muscle quivered in Turner's bland face, yet something in his mild, apparently inoffensive look held the other motionless. "But at least I have sense enough to know just who would benefit by Pietro Lucio's death."

"Sure yuh have. There's two of us, Paul Melwin an' me. But it was Melwin's gat done it. That lets me out."

"The police seem to think so."

"Then what are yuh blattin' about?"

"I'm not as certain as the police. There are a great many people, Mr. Rafferty, living in this vicinity who will tell me things they would be afraid to tell the police. One never knows what a charwoman, or a porter, might happen to see around an office at night. They usually keep what they do see to themselves, but sometimes they talk, to someone they trust."

"Meanin' you." The derby-hatted man's lids were slitted. Two white spots showed at the corners of his thick nostrils.

"Meaning me. The gun that killed Liscio was taken out of Paul Melwin's desk drawer between seven and eight last night. Melwin may have taken it out himself. Or—someone else may have taken it."

"That's a laugh. Yuh ain't botherin' me none with them hints. If you knew somethin' like that yuh'd run to the cops with it."

"Of course. If I were sure. I shall, as soon as I am sure. And that will be—" Doc's hand strayed to his vest pocket. He took an old-fashioned "turnip" watch out of it, snapped it open and glanced down at the dial—"in about three-quarters of an hour, Mr. Rafferty. At exactly nine o'clock I expect a telephone call from someone who saw that automatic taken out of that desk drawer. Someone who'll talk only to me."

Tiny muscles knotted along the ridge of Rafferty's prognathous jaw. There was a tense, electric silence in the store for three ticks of its owner's watch. Then the labor racketeer grinned, sardonically.

"That, Mister Doc Turner, is a lot uh baloney, an' it's got nothin' to do with me, anyways. What I want to know is this. Are yuh buttin' out uh the union set-up or do I have to make yuh?"

"I'll give you the answer to that at nine-thirty—till then you'll have to excuse me. I have a cough syrup on the fire inside and I shall be busy with it from now on." Doc deliberately turned his back and walked away. The prescription department curtain closed behind him...

He leaped soundlessly to a peephole in the partition, peered through it. Rafferty was still standing at the sales counter, but there was no smile on his heavy-featured face now. There was black wrath—and an almost unnoticeable quiver of fear.

After a minute he turned and stalked out through the open door. For all his bulk there was something pantherine about his stride. Something—lethal.

"Who is it, Doc?" Jack demanded. "Who's going to call you up and tell you about the gun being taken out of Melwin's drawer?"

Andrew Turner smiled. "No one. I was not even certain it was Paul's automatic till I read the paper a few minutes ago."

"What the hell are you up to, then? What was the idea of saying that to Rafferty?"

"I was planting a seed in his mind, Jack. A seed of confession. It won't grow unless the soil where I planted it is fertilized with the black loam of murder. But I think it will grow. I'm sure it will grow."

"I don't get you. What are you driving at?"

"I'll explain later. Haven't time now. We've got to get busy." Doc was tugging at a metal ring countersunk in the floor, the handle of a trapdoor to the cellar. It swung up as he spoke. "Listen..."

SOMEWHERE outside a deep-toned tower clock bonged the half

hour. Eight-thirty. An undersized, weazened individual slouched

into Turner's drugstore, his shabby jacket wrapped tightly about

him, its lapels turned up as if to conceal the fact that he was

collarless, but succeeding in hiding the lower quarter of his

face as well. The broad peak of his tattered cap performed the

same function for his forehead and eyes.

Doc, standing behind the sales counter once more, jabbed the key of his cash register with an acid-stained thumb. A bell pinged but the drawer did not jump out as it should.

"The damn thing is out of kilter," he muttered, half-aloud. Then, apparently seeing the customer for the first time, he said: "Good morning. What can I do for you?"

"I got a festerin' sore on me leg here," the fellow whined, pointing to a spot well up on his thigh. "I got it a week now an' it won't heal up. Mebbe yeh kin gimmie somethin' for it."

"That sounds bad," Doc replied, punching the cash register again, with as little result. "Why don't you go to a doctor or a clinic?"

"I ain't got the cash fer a doctor an' if I got to go to the clinic an' wait there half a day I'll get trim out uh me job. Couldn't yeh take a look at it?"

The druggist seemed to be fascinated by the ping of his cash register and its failure to respond otherwise to his pressure on the key. He tried again. Then he sighed; "All right. But you'll have to take your pants down and you can't do that out here. Come inside."

"T'anks, Doc." The man moved to the end of the counter, came around it. Turner held the curtain aside for him, and he went through into the back-room. The druggist followed.

The runt whipped around as the curtain fell behind Doc. One of his grimy claws flashed out and caught the old man by the collar. The other hand darted to the back of the runt's neck. Metal glinted in it, abruptly, and a knife flailed for Doc's heart.

Turner's foot lashed up, plunged into the killer's belly. The kick broke the hold on the druggist's collar and jolted the fellow back just far enough for his stab to miss the druggist's chest. He didn't get another chance. He was caught fast in iron-muscled arms. Steely fingers were on his wrist, were twisting the dagger out of his fingers. Then there was a hand on his mouth, choking back any outcry he might make, and a voice was raised, behind him.

"Gee, Doc! Down in the cellar I was scared I was mixed up on the signal. I knew the first ring meant someone you didn't like the looks of was coming in, but for a second I couldn't remember whether the two after that meant they was getting you to go outside or to come in here. But you had it right. It was one or the other. They wouldn't take a chance on bumping you in the front of the store."

"No. They had to either lure me outside where I could be shot from a moving car or in here where I could be killed silently, and the knifer have a chance to get away." Doc picked up a coil of wire ready on the prescription counter, a pair of cutting pliers, and went to work with them to lash the would-be killer's ankles and wrists securely. "The way they chose makes it a lot easier for what we have to do. All right, Jack. He's safe enough. Put him in that chair over there."

The runt, helpless in the chair at Doc's roll-top desk, whined, "What are yeh goin' to do with me?"

"Give you a chance to tell us why Pat Rafferty sent you in here to stick a knife in my heart." Turner did not look at the chap as he said this. He was taking a bottle from a shelf over the prescription counter, was shaking its yellowish liquid contents, was gazing at it speculatively. "What's your name?"

"Joe." A veil dropped over the killer's glittering orbs. "But I don't know no Rafferty. I didn't have no gun to stick yeh up so I figgered I'd slash yeh and empty yer till before I made me getaway."

Doc set the bottle down on the counter and took out its glass stopper. "You had a gun last night, Joe, when you stood on a chair and shot Pietro Liscio down." He clipped a three-inch length from what remained of the silvery wire that he had used to bind the prisoner, deftly wound about an inch at its end into a small, spiral coil. "Paul Melwin's gun. Was it you or Rafferty who stole it from the drawer in Paul Melwin's desk, and filed the number from it so that it wouldn't be too obviously an attempt to cast suspicion on him when you left it there in the corridor?"

"Yer bats. I don't know what yer talk-in' about."

"No," Doc sighed. "No, Joe?"

HE SEEMED to lose interest in the runt. "Jack. Did I ever

show you what this stuff will do?"

Ransom looked puzzled. "No, you didn't." From the expression on his face it was apparent that he was tempted to agree with Joe in his estimate of Doc's sanity.

"Look at this." The pharmacist held the coil over the unstoppered bottle. The wire broke into flame!

"It burns." Turner said, in a hushed, reverent voice. "Just holding a wire in its vapors makes metal burn. Remarkable, isn't it, Jack?"

"Yes," the redhead answered. "But..."

"I knew it would do that," Doc Turner mused, "but they say it will do something else. They say if you spill it on someone, nothing will happen if he is telling the truth, but if he is lying he'll burst into a flame, like this wire did. I don't believe that, but I've never had a chance to try it out. Now I have, and I'm going to." He picked up the still open bottle, plodded slowly toward the prisoner.

"No!" the fellow yelled. "You ain't got no right..."

"You're not afraid of it, are you?" Doc smiled. "It really can't work that way. Nothing could. Of course you would think nothing could make metal burn just by being held over it. But that's different." He held the bottle over the cringing, blue-lipped wretch. "And anyway, it won't hurt you if you told the truth about the gun and Rafferty." The bottle started to tip, slowly, deliberately.

"No!" Joe screamed, "Don't spill it! I was lying. Rafferty sent me to bump Liscio. Rafferty himself stole the gun an' gimme it. Rafferty..."

"Yuh damned rat!" Doc, Jack wheeled to the new voice. "Stick 'em up," Pat Rafferty said, enforcing his command by a wicked-looking forty-five that snouted at them from his knuckled fist. "Stick 'em up, wise guys!"

He spoke around a plump, black cigar, but what he said had no less menace for that. The two whom he threatened lifted arms ceiling-ward, the bottle still held in Doc Turner's gnarled fingers.

"I t'ought I better sneak in and find out what was keepin' Joe," the man in the checked suit lipped around his cigar. "Good t'ing I did."

"Perhaps," the old pharmacist responded. "But what are you going to do about what you've learned? You don't dare shoot us down. Even if the sound of your gun doesn't bring a crowd running, you're too well known to get out of here without being recognized."

"A smartie, huh!" Rafferty's sneer dislodged the ash from his cigar. It dropped and left the end glowing. "But not so smart as yuh t'ink. Dis trapdoor goes down to yuhr cellar, don't it?"

"Yes."

"That's the way I'm going after I fix the three uh yuh. There's an old sewer pipe down there opens into the ditch outside. They uncovered it just before they quit last night. Nobody's workin' this end of the trench no more, but nobody's goin' to think nothing of me comin' out of it."

"That's right, Doc," Jack groaned. "I saw daylight through a hole in the wall, just now."

"Yeah. All right, guys, say yuhr prayers. Yuh're gettin' it right now."

Doc stared at the black eye of Rafferty's revolver. He saw it twitch, minutely, with pressure on its trigger.

And hurled the bottle he held!

The glinting missile flashed through mid-air—and missed Rafferty! It struck the edge of the counter, smashed...

Flame, yellow, blinding, leaped from that smashed bottle and cascaded over the racketeer. A shot blazed out of that catastrophic flare. The slug plowed a harmless splinter from the floor. Then the flame was gone, and there was only a writhing, blackened form on the blackened floor, a thing unrecognizable as human except for the scream of utter agony that shrilled from it.

The smell of gas was heavy in the air. With it was mingled the smell of scorched flesh.

"THE bottle contained unpurified gasoline," Doc Turner

explained to Jack. "When I made the coil of wire I slipped a

little clump of activated platinum sponge into it, and it was

that which set fire to the fumes."

"That's the stuff they use in the flame-less cigarette lighters, isn't it?"

"Exactly. It's black and from a little distance you and Joe didn't see it. Then, when Rafferty was about to shoot I took a chance on his cigar igniting the gasoline. It did. That's all there was to it."

"No," Jack objected. "It was a good trick, but it was just the finishing touch. What made you so sure it wasn't Melwin who had Liscio killed?"

"Oh, I knew that as soon as I saw the gun under the chair. There isn't anyone, today, who doesn't know every weapon is numbered, and that the molecular structure of the steel where the numbers have been stamped in are changed so that they can never really be destroyed. Certainly Paul knew that, and he'd make damn sure a killer he hired wouldn't leave it around to be traced to him. Therefore it must have been left there with a purpose, which could only be to cast suspicion on him. Who but Rafferty would want to do that, knowing that Paul would never let his employees be victimized by a racketeer?"

"So you baited Rafferty by letting him think he had to kill you to cover himself. The seed of murder you planted was the seed of your own murder."

"It grew pretty well," Doc Turner smiled. "And I've got a notion another seed I planted today is going to grow too. A seed of kindliness in Ida Melwin's mind."

That seed did grow. It grew into a whole garden, high in the Catskills. Its flowers are happy faces, healthy bodies, belonging to children who would have grown wan and sickly in the torrid summer of the slum. They call it Doc's Camp down on Morris Street, but it is supported wholly by Ida Melwin, née Ida Gorchik.