RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

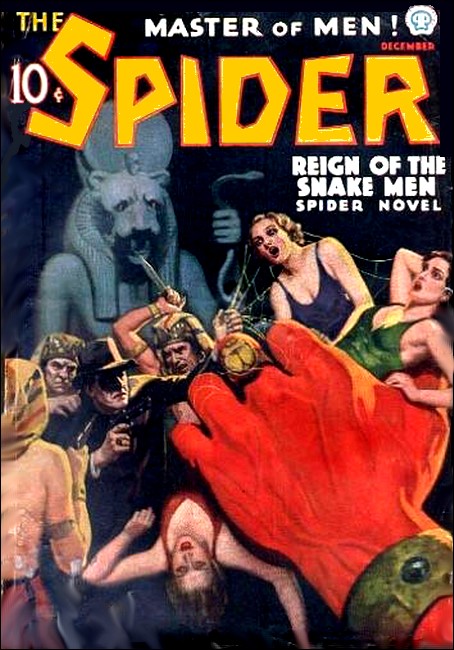

The Spider, December 1936, with "Death Set-Up in Yellow"

In the crime-shot murk of Morris Street, where alien tongues mingled, Doc Turner could count up to three in any language—and fight the Living Death and the Scroll of Ancient Tortures at the drop of a hat.

ANDREW TURNER'S fleshless lips tightened under his bushy white mustache. A muscle twitched in his age-seamed face and his frail, stooped figure was abruptly taut. His veined eyelids drooped to hide the sudden flare in the faded blue orbs beneath them.

"That's queer," the old druggist muttered. "Damned queer."

In the deepening dusk, Morris Street presented its usual picture of bustling activity. Along the slum thoroughfare shawled housewives chaffered with leathery countenanced, hoarsely abusive pushcart hucksters. Grimy, half-clad urchins screechingly escaped certain destruction under the juggernaut wheels of rushing traffic. A homecoming Sicilian laborer breasted the swirling throng, and two long-bearded old men plodded their ancient path toward the sunset minyan in the synagogue on Hogbund Place.

On the other side of the debris-strewn gutter, a van-like truck stood against the curb, Yee Gow Steam Laundry lettered in gilt on its high green side. From the doorway of his dusty pharmacy Doc Turner had been idly watching a stocky Chinese in overalls carry one huge white bundle after another into a steamy-windowed shop across the sidewalk. He had been only half aware of the Oriental and his shouldered burdens...

Until a bundle had moved, grotesquely, as though it contained something alive!

The truckman vanished into the dim obscurity within the store. Dim figures moved briefly among half-seen shadows. Then the Mongolian was out again. He sprang, amazingly lithe for his muscle-bound bulk, to the truck's driving seat. The great vehicle lurched, roaring, into instant motion.

The nostrils of the old pharmacist's big nose flared, momentarily, as if through the familiar reek of decomposing refuse, of burned gasoline and sweaty, unwashed bodies he had detected the odor of some circumstance obscurely evil. A vague excitement stirred within him.

Maintaining the appearance of a casualness now entirely counterfeit, Turner stared at the shop across the street. Relic of the tree-shaded suburban road Morris Street had been when he first came to it, more years ago than he cared to recall, a two-story, ridge-roofed wooden structure was crushed between two tall tenements. Between the upstairs windows that were blinded by black shades never raised, over the door through which the weirdly animate bundle had been carried, a square, red signboard creaked from a rusted iron bracket. Ching Foo Laundry, read its faded legend.

Even in this neighborhood of aliens the dweller in that ramshackle structure was set apart in a singular isolation. Micks and Heinies, Polacks, and Wops, Jews and Gentiles were united in a common distrust of "th' Chink."

Perhaps it was some trace of that racial heritage of hate and fear that brushed Andrew Turner's spine with an unaccustomed feathery chill. Perhaps it was instinct, the strange sixth sense he had acquired through years of battling the criminals who prey upon the very poor, that ridged his grizzled jaw with sudden determination. At any rate, before the Yee Gow truck had rumbled a hundred yards he was trotting across the street.

A BELL jangled, somewhere in the shadows, as he pushed

through Ching Foo's door. A crudely carpentered counter blocked

Doc's progress just inside.

They were, after all, nothing but two cloth-wrapped batches of linen, wet-washed and delivered for finishing. It was some trick of vision, some illusion of the dusk, that had made him think one had moved on the truckman's bowed-down shoulder. Some flicker of the fading light seeping through the "El's" network, perhaps.

Two! The old man remembered that three bags had been carried into the shop. Distinctly he recalled seeing the Mongol cross the sidewalk three times. Where was the third...?

"Hallo." Ching Foo shambled through a curtained aperture in the partition. "Good mo'ning."

"Good evening."

The Chinese was tall, thin almost to the point of emaciation. His oddly skewed eyes glittered, two points of black light in the gloom. His sweat-wet undershirt clung to his yellow skin, and the sleazy black stuff of his pantaloons fluttered about his long legs. The straw sandals he wore flap-flapped on the bare wood of the floor so that it seemed that not one but two men shuffled toward the counter.

Or had Doc actually heard the footfalls of someone else, behind the partition? Of someone who stood now, just inside that curtain, silently listening?

"What can do foh you?" The grimace of the sallow lips must have been intended for a smile. "Mebbe send to youh dlugstoh acloss stleet foh washee?"

"No." Nothing remarkable in Ching Foo's knowing who he was. "I want to find out how much you charge, first." But why, when it was evidently so difficult for him to express himself in English, had the Chinese ventured upon so long a sentence? "I thought I might be able to save money." Was it to identify Doc to someone else?

"Shoo you save money. Eight cents pound, fi' cents foh shiht."

"Cheap enough. I'm paying ten and eight. No wonder you're so busy. There's a lot of pounds in three big bundles like you just got from the steam laundry."

"No tlee. Two." The face Doc scanned with unobtrusive keenness remained an inscrutable yellow mask, utterly expressionless. But the black glitter blinked out in the almond orbs, as though a membrane had dropped over them to hide some sudden alarm. "Two. See." The hand that waved to the bundles on the floor was curiously like a claw...

And at the tip of one pointed nail there was a tiny scarlet spot! Like a drop of blood.

DOC shrugged, in dismissal of a subject that held only

desultory interest. "I'll think it over, Ching Foo. I hate to

make a change, but the way my business is, I have to watch

every penny. I'll let you know."

"Do velly good wash, i'on." The other wasn't ready to let him go. "You come inside, I show." A portion of the counter hinged back to the yellow man's thrust. He darted through the opening. "I got velly fine shiht jus' finish." The saffron claw caught the druggist's upper arm.

"Not now. I've got to get back to the store. I left it alone, and..."

"You come." The hold on his arm tightened. Doc tried to jerk away from it, failed. Ching Foo was dragging him through the opening in the counter, was dragging him toward the black curtain. There was incredible strength in the skinny, long-nailed fingers, in the stringy body that had seemed a bag of skin and bones ready to fall apart at an unduly rough touch.

A shudder quivered through the pharmacist's feeble frame, more of repugnance for the Oriental's clammy-cold nearness than of fear. He snatched at the long table, dug heels into the splintered floor, succeeded in stopping the swift rush toward the mysterious precincts behind the partition.

"What..." he gasped. "What...?" and choked off as he saw the black curtain belly outward, forming itself to the contours of an unseen shape.

There was someone else, then, and he was coming to aid Ching Foo. Doc couldn't fight two of them. A yell for help formed in his throat...

"Vot ees?" The thin, piping exclamation cut through the jangle of a bell, far back. "Meester Toiner! Vot ees mit you?"

The Chinese's clutch relaxed, permitting Turner to twist to the open entrance door. An undersized, swarthy youngster gaped open-mouthed in its embrasure, his hair a kinked, tight ebony cap for his skull, his features darkly Semitic. Behind him there was the crowded turbulence of Morris Street. Familiar faces, familiar things, were only six feet away, not distant by eons of time and space, as an instant before they had seemed.

"Abie!" Never before had Doc been quite so glad to see his snuffling, shrewd little errand boy. "You brat!"

"I come beck from sahper und de store's full mit customers und you ain't dere. Somevun tells me dey seen you come een here."

"I was just talking to Ching Foo about giving him my work. He wanted to show me how well he can do it." Doc wheeled unexpectedly, swept aside the curtain. This was his chance, with the door open, with Abie to summon aid if it were needed, to see what was behind it. And who.

Ching Foo made no effort to stop him.

The room beyond the partition was very large, but no living being stirred within it. There was a clutter of ironing boards, tables, piles of laundry, a charcoal brazier on which flat-irons heated. Broken-paned, grimy windows made gray oblongs in a wall at the rear as fading light seeped in through them from the alley behind. They were striped with iron bars red with rust.

Was there furtive movement in the darkness at the head of those stairs? Was there the glitter of baleful, watching eyes? The old man could not be quite sure.

"Dees ees a fohnny t'eeng." A rattle behind him turned Doc around. Abie had picked up from the counter a wooden frame that was strung with wires on which vividly colored wooden beads moved loosely. "Vot ees eet?"

"That is to count," Ching Foo said, drawing in a hissing breath. "It is how they teach alithmetic in my countly. When you leahn you must not fohget. If you make mistake—count tlee when should be two—moh betteh you say nothing. If talk too much, too bad foh you."

HE was just a bobbing-headed, menial yellow coolie,

explaining one of his native Oriental ingenuities to a shabby-clothed little boy who, because he was white, was his master. One

of his fluttering, jaundiced hands made a queer gesture, its edge

pulling across his abdomen as if it were a knife, slicing. And

his almond-shaped, secretive eyes slid meaningfully to the aged

druggist, slid instantly away.

Andrew Turner's own eyes were bleak, expressionless, and his wrinkled features were very grim.

"We give things like that to babies to play with, Abe," he said tonelessly, "in America, and some foolish people tell them stories about goblins. But only babies are frightened by fairy tales. Come on—we've got a business to take care of."

The street lamps came on as Doc Turner nimbly dodged traffic, crossing Morris Street back to his store. Daylight, still lingering, paled their effulgence. But somehow it seemed to the old man that the pallid rays struggled against something else, against some dark impalpable fog that had rolled up, almost invisible, from the East.

And the nape of his neck prickled with the consciousness of the Oriental's slitted, inscrutable gaze upon him.

"HELL, Doc," Jack Ransom grunted. "If you took that yarn

to the cops they'd laugh at you."

"Of course." The old man prodded the corner of the white-painted showcase nearest his store door with an acid-stained thumb. "If it wasn't for the way Ching Foo acted, and his cryptic threat, I'd be inclined to laugh at myself. But it did happen, just the way I told you, and it was a dead giveaway that something—nasty—is going on over there. The Chinese lost his head, of course, when he tried to drag me inside and when he threatened me. That makes me certain he's only an underling. There is no slyer, shrewder criminal in the world than the Oriental. And none crueler or more unscrupulous."

"Which means that if we mix in this thing we may be biting off more than we can chew. And, after all, what business is it of ours what the Chinks are up to among themselves?"

"No," the old druggist murmured. "No, I don't suppose it is any of our business." He smiled, wearily. "Let's forget it."

"That would be smart."

"You know," Doc sighed, "that bundle was big, but it wasn't quite big enough to contain a man. Maybe there was a small woman in it, or a child."

Ransom's big hands, which had been lying flat on the glass showcase top, curled slowly, till they were hard, hairy fists.

"They wouldn't bring anyone here to kill him quickly. That would be silly. But I'm sure there was blood on Ching Foo's finger." The druggist's tone was low, musing, indifferent. "I was reading the other day about Chinese tortures. Quite ingenious. There was one called the 'Death of a Thousand Cuts.' An artist at it, the author said, can keep his victim alive for a week while bit by bit he shaves away his flesh. And then there was one interesting device a Northern bandit chief used. He slit his captive's skin, inserted the end of a hollow straw and had his men blow air through it while the skin tore slowly away from..."

"Damn you, Doc," Jack groaned. "You win." A tiny muscle twitched in his freckled cheek. "How do we start?"

There was no hint of triumph in the old man's voice, but a certain vibrant thrill crept into it. "By taking care of the bird who's been lounging outside the store all evening," he responded, "keeping a very watchful eye on me."

Jack growled inarticulately, wheeled to the door.

"Careful." Doc's sharp ejaculation froze him. "We daren't tip off Ching Foo, and his invisible master, that we're up to something. Come behind here and I'll let you take a peek at their lookout."

MORRIS STREET was quiet, deserted. The latticed shadows of

the "El" lay undisturbed on the greasy-wet cobbles of the gutter.

Broken crates, vegetables too rotted for even bargain prices to

sell, littered the lonely sidewalk as the only reminder of the

shouting raucous pushcart market that had earlier made the block

a bedlam. But a wizened, shrunken man, wrapped in a black ulster

three sizes too big for him, lolled against the corner-post of

the store, draggled hat pulled low down to hide his face.

"They can see him from across the street," Doc whispered. "If anything happens to him—by the time we can get into that old house, we'll find nothing there. And remember—it is easier to hide a dead body than a live prisoner."

"But..."

"But if I go quietly home, and to bed, they will be sure I have thought better of my defiance of Ching Foo's warning. Do you understand?"

"No. I..."

"There is only one man. He can't follow both of us. Listen..."

For perhaps five minutes more voices murmured in the sleepy old store. Then Jack strode to the door, opened it. "Oh, Doc," he called, half-turning. "Which was it I'm to take before going to bed, the pills or the liquid?"

"The liquid, son. A teaspoonful in a glass of hot water. Take the pills in the morning, and you'll be all right."

"Thanks. I'm glad you don't think it's anything worse than a little rheumatism. I sure was worried. Good night."

"Good night."

The old man yawned, shambled back to his prescription room. After awhile he came out again, more stooped, more feeble appearing in his shabby overcoat. He switched off the store lights, shambled out of the door, closed and locked it.

"Ho hum," he mumbled. "Another day gone."

The fellow at the corner of the now darkened window did not move. He seemed to be contemplating his broken-toed shoes with absorbed interest. Doc went past him, dragging slow, tired steps. He crossed the side street, ambled slowly down the block.

The man in the too-big ulster got into motion. He was momentarily in sight, darting across the street the druggist had crossed, then he merged with the shadows that lay thick along the drab fronts of the tenements beyond. His tread was curiously silent, so that he was able to catch up to the old druggist unobserved. He was only six yards behind Turner when the pharmacist reached and turned the next corner.

His trailer paused. An evil grin twisted the saffron countenance he no longer troubled to conceal. His hand darted up, and to the back of his neck. A vagrant gleam of light flashed on the blue steel of a long, keen knife, cleverly weighted for unerring throwing...

The Chinese were taking no chances on Doc's interfering with their plans. His confidence that all they had intended was to watch him had been terribly misplaced!

His plodding, oblivious target moving too slowly to demand haste, the assassin poised momentarily on the balls of his feet to make sure of his aim. His abnormally developed biceps bulged for the throw...

A black bulk catapulted out of a basement areaway. Flesh thudded on flesh, bone crunched sickeningly. The hatchetman smacked the sidewalk hard, quivered and lay very still.

Andrew Turner came unhurriedly about, shambled back toward the squat, bulking figure who stood astraddle the unconscious thug, breathing hard. "Neat," the old druggist murmured. "That was neatly done, Jack."

THE roof of a city tenement is a jungle of slanting

skylights, erect vent pipes, jagged-topped chimneys. But it is

easy to reach unobserved, especially at night. There is so little

to steal in the bare flats it covers that no one bothers to keep

backyard fences in repair, or to lock basement doors.

"They might be watching Morris Street," Jack chuckled, "with all their slant eyes, but they wouldn't expect us to be slipping up on them from the street behind, like this."

"We've got a lot to do yet, son, before we can afford to laugh." The top of Doc Turner's head was a fuzzy silhouette against the sky's night glow, jogging the straight black line of the parapet over which he peered. "The roof of Ching Foo's place looks terribly far down from here."

The youth knelt, joined him in looking over the low wall. "Yeah. That's why I wondered just why we didn't try to go through one of the third-floor flats. That would have been easier."

"There would have been too many explanations to make, and some hysterical woman might have screamed, giving us away—hello!" Doc said in sudden observation. "Our friends seem to be receiving a late visitor. Look."

The strangely assorted couple stared down into a stygian- walled gut that was floored, two stories below, by the shingled roof of Ching Foo's old house, slanting either way from its sagging ridgepole. Still further down was the sidewalk of Morris Street, just visible past the "El's" viaduct.

The soft burr of an idling, powerful motor came up to them, the muffled clang of the bell that was actuated by the opening of the laundry door. A glimmer of light seeped across the sidewalk, was blotched by a bulky figure whose nature was indecipherable from their vantage point. Then the light was gone.

"His car isn't waiting." Sudden motor roar told Jack that, the whimper of tires taking hold of slick cobbles. "I wonder what's up."

"We'll soon find out." Doc stood up. He unbuttoned his overcoat, hiked up its tails. His hands moved in curious circles about his slight form—and coil after coil of rope fell to the tarry gravel underfoot. "That stanchion over there looks strong enough. Tie the end of this to it, and make sure your knot will hold."

"Damned right I'll make sure." Jack picked up the end of the cable Doc had unwound from his waist. There were knots in it at intervals, handholds for a climber. "I'm not anxious for it to let go when I'm halfway down."

"I'm sure you're not. And if it holds your weight, it'll hold mine."

"Yours!" The youth jerked around from his task. "You're not going down there, Doc. You can't..."

"Maybe you're right." The old pharmacist tugged, making sure that the rope was securely fastened. He threw its free end over the parapet, paid it out till it swung free. "But you can't stop me." He was over the wall before Jack could interfere, was going hand over hand down the slim, swaying filament.

"You ought to be spanked," the carrot-top grunted, minutes later, as his feet found support on the dry, steep shingles below. "You..."

"Hush," Doc hissed warningly. "Listen."

AT first Ransom could make out only the low, sleepless

growl of the never-sleeping city. Then he heard another sound,

from beneath his very feet. A moan, almost inaudible, of someone

in pain.

"There's a hatch here," the druggist whispered. "I've been poking under its edge with my knife, and I've managed to get its fastening open. They wouldn't worry about making that secure, not expecting anyone to try getting in from up here. Help me to lift it."

Jack dropped to his knees, got hands on wood that was rotted, crumbling.

"Wait," Doc murmured. "I hear a train coming."

The rumble came nearer, was thunderous just beneath their perch. The scream of the old hinges jabbed Jack with terror of discovery. But the trapdoor swung over and down again before the roar of the train passed, and he realized that it had covered the sound that otherwise would have betrayed them.

The moans were a trifle clearer now, but still distant-seeming, muffled. Something in their timbre brought out cold sweat on the youth's palms.

The blackness into which he stared was weirdly striped with long lines of yellow brightness that came from the rear of the house and ended abruptly just below. Jack blinked at them, wondering what they were, heard relieved breath hiss from between Doc's teeth.

"An attic. And light in the room just below shining through between its floor boards. We've got to be doubly careful, now, not to make any sound getting down there."

Ransom groped within the hatch-edge, feeling for stairs, a ladder. There was none. "I'll have to chin myself down, help you."

"Get going. Hurry."

The sufferer below moaned again.

The youth's stalwart body slid down through the aperture. Corroded metal, sheathing its edge, cut into his palms as they took his weight. He could not—quite—reach the attic floor with his extended toes. He'd have to—drop.

He let go his hold, jolted downward. His feet thudded on wood. It sagged beneath his weight—did not come back. Sagged further—broke with a vast splintering of aged, insect-riddled fibers, with a choking, blinding gust of acrid dust!

Light blazed through the dust, light bursting through the shattered flooring that had not been called upon to bear any weight for decades. Jagged edges of broken boards ripped Jack's clothing, caught him momentarily, let go. He sprawled down into the lighted room, pounded down upon a stronger floor.

He rolled, gasping, spluttering. Something moved in the dust cloud billowing above him, and then he saw a black, squat automatic snouting at him from a yellow hand. Saw Death peering at him out of a saffron, inscrutable face.

A SHRILL sing-song pierced his ears, not from the gun

wielder, Ching Foo, but from someone else, close by. Ching Foo

didn't shoot. Inexplicably the automatic withheld its fire.

But someone was thudding to the floor alongside him, whispering, "No noise. Death, if you make a sound." A round, oily face hung over him, hairless, yellow as the yolk of an egg, infinite menace in its birdlike, slanted eyes, in its incongruously tiny, red lips. Hands, deft, swift and appallingly strong were thrusting a fag into his mouth, were lashing his arms, his legs with a hairlike silken cord that he instinctively knew was stronger than so much wire.

"You are fortunate for the moment," the oily-countenanced Oriental lipped, "that our need for silence is greater than our desire to punish you for your impudent entrance. You will be more fortunate if the tumult you have already made has not been heard by one who even now mounts from the lower floor."

Precise, the intonation, the clipped syllables of that speech, but a hiss ran through them like the hiss of a virulent, deadly snake. Virulent and deadly, the look in the Mongolian's eyes. Jack knew, in that instant, that Ching Foo's bullet would have been more merciful than what this other had in mind.

Somewhere there was a heavy footfall, a fumbling, hesitant tap on a door that was not in this room. The stout Chinese heaved to his feet, waddled away. Jack, following him with his eyes, saw him go out of the room and shut the door through which he exited. Heard his shrill sing-song ring out again. Then Jack rolled his head to look at Ching Foo.

He saw the laundryman, standing above him, the gun an ominous adjuration to silence. But he saw something else, that till now had been hidden by the other Oriental's bulk, and Jack's scalp tightened, became an icy, tight cap for his skull.

A spike had been driven into the wall, there, high up. A silk cord, like that which bound him, had been fastened to it. It was stretched taut by the weight of a Chinese boy who hung from a noose in its other end, a noose that looped not his neck but his bloody forehead! Cutting into it, excruciatingly.

The lad—he might be ten years old—could relieve himself of that agony by resting his weight on his toes that just touched—a pan of glowing, red-hot charcoal!

Jack Ransom knew now what the odor had been that had filled him with queasy panic, there on the roof.

The tortured child was naked. Little quivers ran over his yellow, perfectly formed small body. His eyes were open. They stared at Ching Foo—good God!—stared at him with a strange, terrible defiance that he could not utter because he was gagged.

NAUSEA twisted at the pit of Jack's stomach, and he pulled

his gaze away from that picture of unrealizable suffering. He

became conscious of voices, coming through the wall behind

him.

"Enter, Yang Su," he heard in the oily accents of the man who had tied him up. "You will pardon me that I use the English we both know, since unhappily your dialect of the Manchus is as unfamiliar to my Southern ears as my mother tongue to you. And you will accept my humblest apologies for the meanness of this place I bid you enter, that is not fit to be honored with the presence of so august a personage as the patriarch of the Brotherhood of Chinese Merchants in this infidel land."

"Where is my son, Ka Sin?" Jack had thought the Chinese incapable of emotion, till he heard the anguish that throbbed in that question. "What have you done with Yang Toy?"

"Ah, you have searched Chinatown in vain for him. Even you, to whom every inch of that abode of our Celestial race is an open book, have not been able to discover where he is hidden. Nor, if you search from now till that far-off day when the Sun-Dragon devours the Earth, shall you lay eyes upon him again."

"Why then have you bidden me here, to this dog's abode, in such secrecy?"

"First, because I dared not place myself within reach of those who obey your slightest wish. Second, because I wished to make a bargain with you."

"What bargain, when you have told me Yang Toy is forever beyond my reach?"

"Yang Toy dies, Yang Su, to pay for my brother whom your hatchetmen sent to our divine ancestors. That you cannot avoid. If you will agree, here and now, that I and my servants shall be unmolested in their purveyance of the juice of the poppy in this country, he dies mercifully and at once. If you refuse that promise, if you tell me once again that you shall continue to betray my servants to the white officers who would halt our Ancient trade, then I shall read the Scroll of Ancient Tortures to him from end to end. You know what that means."

The horror in the convulsed face of the child who hung by his brow told Jack enough of that meaning. The horror in the father's voice told him more...

"I know, you devil. I know." There was a long pause. The white man saw something in Yang Toy's eyes, something beyond belief. It was a prayer wrung from the pain itself. But it was a prayer that the father who was, unknowing, so near to him should remain true to his trust!

JACK'S body was bathed with cold sweat. His lips were dry,

cracked...

"I have decided." Yang Su's tones were utterly without emotion as they came muffled through the partition. "I have sworn upon the bones of my ancestors, of Yang Toy's ancestors, to protect my people from the living death of the poppy flower. I shall not break that oath."

The lad slumped. But there was a look of happiness on his tortured little countenance...

"I go now in peace, as I promised," Yang Su continued. "But the time of our truce expires at the Hour of the Dog, and then I shall..."

"No!" Jack tried to scream from behind his gag. "Don't go. He's here. Right here within five feet of you." He knew it was futile, hopeless. The brave boy was doomed. He himself was doomed... If only he could get Yang Su to look through that door! Jack's heels lifted, banged down...

Ching Foo gurgled something, his evil countenance leering, the automatic jerking up in his pointed claw... That face jerked, out of the range of Jack's vision. The gun, unfired, dropped to the floor!

AMAZED, unbelieving, Ransom rolled. The Chinese was

clawing at his throat in frenzied agony. His heels were clear of

the floor, and he was jerking from a taut rope that came down

from the jagged hole in the ceiling!

That rope had spaced knots along it... The Mongol's complexion was no longer saffron, it was purple, engorged. His eyes bulged from their slanted sockets... He was a limp, lifeless scarecrow, hanging from that tight cable.

Doc Turner jumped down through that hole, sprawled, came erect, clutching the gun Ching Foo had dropped. He leaped to the door, flung it open.

"Wait, Yang Su!" The age-thinned voice crackled with vibrant energy. "Reach, Ka Sin! I've promised you no truce. Hour of the Dog or the Rat, I'd just as lief put a bullet in you as look at you."

Jack saw the portly Mongolian whirl, saw his corded, shaking hands dart above his head. Ka Sin's small mouth pursed. "I told Ching Foo you were dangerous. For bringing you upon our trail he shall die the Death of the Bamboo Shoot."

"Guess again," Turner purred. "He's dead already, of breath-failure. Yang Su, your son is in here. Go in to him quickly. He needs you."

The Oriental gentleman who brushed past Doc was short, but even in his eager haste dignity clothed him, from his anxious eyes to the little gray wisp of a goatee straggling from his chin. He trotted across the floor...

Ka Sin's left arm flicked down. There was a knife in it, springing out of his sleeve. The gun in Doc's hand pounded. Once. Twice.

Ka Sin's knife clattered harmlessly from his nerveless hand. Ka Sin himself slumped down atop it, just as harmless—because there was no longer any life in him.

Doc Turner whipped around. "Jack! Are you all right?" Then he saw the gag in the redhead's mouth. He came to him, ripped it loose.

"A couple of bruises, Doc, but otherwise fine as silk." Jack had hard work to keep from looking at the father and son behind him, but he knew, somehow, that afterwards they might resent having exposed, to Occidental eyes, the emotion that was sweeping them now. "Took you long enough to drop down and find out, though."

"The rope swung away, and I had to be very careful not to make any noise while I crept along the roof to get it back. Your life, and Yang Toy's, wouldn't have been worth two whoops in hell if Ching Foo had heard me."

"Doc."

"What?"

"I'm damned glad we decided to mix in these Chinks' affairs."