RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

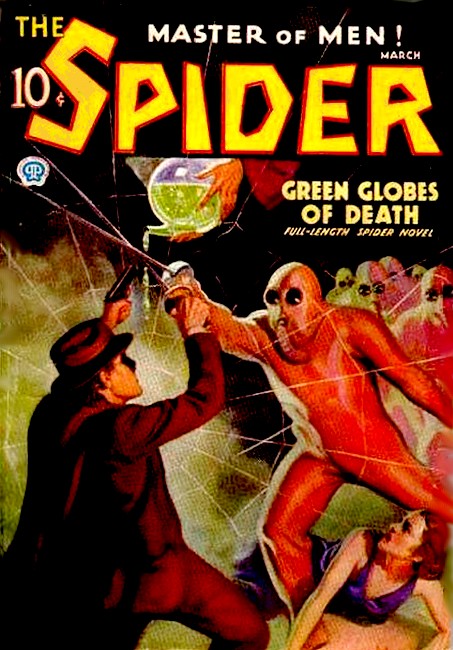

The Spider, March 1936, with "Doc Turner's Kidnap Cure"

Doc Turner knew from Klingel's mute wretchedness that human wolves were preying on Morris Street once again... But he didn't foresee that a piece of paper and a drug-injection would nearly make him cold beef on a butcher's block!

DOC TURNER saw that the man's fat-swollen hands were quivering as they pressed down hard on his sales counter. The silver-haired druggist was dwarfed by the other's massive frame, magnified as it was by the white butcher's apron confining it. Otto Klingel was big-paunched, double-chinned, balloon-cheeked, but the usual ruddiness of his rotund jowls was a doughy yellow-white, and behind the china-blue glaze of his small eyes, little lights crawled that were tiny candle-lights of some marrow-melting dread.

Doc finished wrapping the bottle of bromo seltzer, shoved it across the counter. "Ten cents," he said.

Klingel jumped as if a gun had been fired in his ear, peered wildly about him. Then he had pulled himself together with visible effort, was shoving sausage-like fingers into a pocket under the apron. His hand came out—and coins splattered on the counter, the floor, rolled away to clink against dusty show cases.

"Ach!" the big man erupted. "Ach, sooch an Esel!" He started to bend to the spilled small change...

"Wait!" Turner stopped him. "Abie will pick them up for you." His voice rose. "Abie!"

"Oy! Here I am." The undersized, swarthy, Semitic-featured urchin shoved through the shabby curtain filling the doorway to the prescription counter. Doc motioned wordlessly to the scattered coins, keeping meanwhile his puzzled look on Klingel.

"What is it, Otto?" the old pharmacist asked softly. "What's the matter?"

"Madder?" the butcher splurted. "Haff you nod seen vot der madder iss? Haff you not all veek seen dem dere?" His columnar arm jerked stiffly toward the drugstore's open door, gesturing across the teeming bustle of Morris Street.

"El" pillars framed a drab tenement-house front otherside the rubbish-strewn clamorous gutter. The building's street floor was a butcher shop, behind whose gleaming window, red sides of beef were impaled on rows of hooks and pink-fleshed chickens were appetizingly arranged on a white marble floor. Plump, brown hares hung in a wind-ruffled string to one side of the doorway. A picture of cleanliness and prosperity that shop, quite incongruous in the slimed and poverty-riddled slum.

A man dashed across its front, back and forth, with a strange, hurried ferocity. He rushed along the sidewalk, wheeled abruptly opposite the butcher's door, threw himself past the shining window, spun and ran back again to twist and repeat the maneuver over and over again with monotonous, savage persistence.

A hunger not wholly physical was manifest in every starved line of his thin body. He was gaunt-faced, hollow-eyed, that human mechanism, animated by a driving malevolence. He yelped as he ran and his shrill cries, wordless at this distance, were like a wolf's famished barking. Andrew Turner thought of a caged wolf he had seen once in the Zoo, and there was little difference between the slaver-mouthed beast and the human at whom Klingel pointed save that he ran erect and a frayed tan overcoat flapped against his fleshless shanks.

Pinned to the breast and on the back of that overcoat's shoulders were two oilcloth placards lettered in virulent red. KLINGEL UNFAIR TO LABOR! the scarlet letters shrieked their message. DON'T TRADE WITH HIM!

"Unvair to labor," Klingel snarled. "Vot labor, hein? Me und mein vife Helga, by ourselfs ve tend der shtore und mein leedle Sohn Karl he deliffers orders after school. Den comes dis Clerks' Society und says I must a man hire for thirty tollars a veek und anoder ten to de Society pay. Ven I say I can afford it not they say raise the price uff your meat. Raise de price! Ach! Can dese poor people pay efen a cent more on de pound? Dey must go without if I the price raise. So dey put deir Schweinehunde, deir pig-dogs, to run und bark in frondt uff mein shtore..."

"Meester Toiner," Abe now broke in, straightening with his grimy hands clawed about the change he had retrieved, "dey been around to all de stores on Morris Stritt andt dey all say eef Meester Kleengel joins up dey weel too."

"Shoor," the butcher spat. "Klingel iss on Morris Street de longest und Klingel makes de most money, so let Klingel fight. Vell Klingel is tired from fighting und he giffs in."

"You're lying to me, Otto." Doc's seamed countenance was bleak. "All week you've laughed at the pickets, told me your customers were paying no attention to them. Even if they were, your Dutch stubbornness would never let you surrender. Something else has happened today, something that's twisting a knife inside that fat carcass of yours. What is it?"

Klingel stared at Turner, anguish now wrenching his livid lips. "I—I cannod say. I dare nod say." Then he had whirled around, was lumbering through the store, out into the street, in clumsy flight. A high-piled truck bore down on him, he escaped demolition by a hair's-breadth, reached the opposite curb and skittered for the sanctuary of his own door. The picket, wheeling at the end of one of his blind dashes, collided with him.

Klingel's bellow was an insane roar. Doc saw a hamlike arm rise and fall, saw the tan-coated man go down under the ponderous blow, to sprawl, twitching on the sidewalk. The butcher dived into his shop and the door slammed closed behind him.

"The fool!" Turner gritted, coming out from behind his counter. "Now he's done it." Moving with an agility astounding for his age he was across the street, was kneeling beside the prostrate fellow before anyone else quite realized what had happened. Then there was a close, jostling crowd about him, a polyglot jabber in his ears, the fetid stench of unwashed, sweaty bodies in his nostrils.

Doc looked up into peering, excited faces; dark, Latin faces; high cheek-boned, round molded Slavic faces; faces with the massive lower jaws and broad temples of the ould sod; the hook-nosed swarthy faces and keen, suffering eyes of the ancient race that has no home anywhere, and everywhere is at home. These faces were those of his people, of his poverty-ridden, squalid people whom he had served for more years than he cared to recall and who would obey his every wish because they knew him as their only friend in this bewildering, alien land.

"He's in a fit," Turner said, his rheumy eyes sweeping those crowding countenances with a significance that did not go unobserved. "He's fallen in a fit. Luciano, you and Pat Shea pick him up and carry him over to my store. Take him into my back-room and then clear out."

The hulking laborers he had named hunched forward to obey him. Others, too, moved in that crowd, shoving out of it tight-lipped and furtive. These were the few, a bat-eared and blank-visaged Polack, a beshawled Lithuanian housewife, a stooped ol' clo's man who had seen just how the picket came to be lying there. A policeman was coming from around the corner and they would not be there for him to question. They would not be there to lie for Doc Turner, although cheerfully they would lie if perchance it became necessary.

"What's going on here?" the patrolman roared, thrusting a blue shoulder through the throng, black nightstick clutched in his big-knuckled fist. "What's the disturb—Oh hello, Doc! You mixed up in this?"

"Yes, Clancy," Turner lifted to his feet. "Poor fellow's an epileptic but you won't have to call an ambulance and lose your time off making reports. I'll save you the trouble. I'll bring him out of it and see that he gets home safely."

"Ye've got somethin' up your sleeve," Clancy grinned understandingly. "But seein' as how it's you... Move along there, youse birds. Move along. There ain't nothin' more to see."

HIS swaggering show of authority broke the cluster, sent

its components hurrying about their business, or lack of

business. Doc turned to the door of the butcher-shop, rattled its

handle. The portal was locked, no one in evidence within. Otto

and his Helga had retreated to their flat in the rear to nurse

their trouble in solitude, as the polar bears they resembled

retreat to an iceberg cave to lick their wounds. What was that

trouble? What was the fear that held Klingel in its grip and

tortured him till the peace-loving German had lashed out at his

tormentor in an eruption of uncharacteristic fury?

Crossing back to his own pharmacy Andrew Turner felt an accustomed thrill run through him. Matters were stirring once more on Morris Street, there was work once more for the pharmacist who was so much more than a druggist. Age-bowed, frail and feeble-appearing, the old man had time and again sallied from his ancient shop to challenge the hyenas who prey on the very poor. To challenge and defeat them. Many stared out through prison bars cursing the white-mustached, almost timid-appearing old man who doddered bemusedly behind his counters till there was need for him to come out from behind them. Others lay in unhallowed graves...

"Meester Toiner!" Abe's high, agitated squeal greeted him. "Lookit dees." The boy's dirty paw thrust a paper at his employer as Doc brushed by Tony Luciano and Pat Shea. "Shall I put eet de Coughex in de vinder?"

Turner's bushy eyebrows twitched. "Wait. I don't know if I need Jack yet." The blue carton Abe held in his other hand was a signal to Jack Ransom, the young garage mechanic who was Doc's mailed fist on his forays. "I don't know what this is all about."

"Shoor you need eet, Jeck. On de paper eet stends..."

Doc glared at the sheet the boy had given him, reading the crudely printed words it bore. "Good Lord!" he exclaimed. "That explains—where did you get this, Abe?"

"I peeked eet up mit Meester Kleengel's moneh. From hees pocket eet must have fallen oudt."

"And you palmed it to give it to me after he left!"

"Vell." Abe's shoulders rose in the inimitable shrug of his forbears and his jetty eyes danced. "How aboudt it de Coughex?"

"Put it in the window. Of course, put it in the window. We've got to get busy, and in a hurry." The druggist's tone was abstracted. He was reading the note again, the sinister, brutal message, and the look that had come into his wrinkled face would have sent a thrill of fear through its writer had he been there to see it:

"We're tired of monkeying with you," the letters whispered. "We've got your brat and we'll go to work on him if you don't come across damn quick. How would you like to have him delivered in chops or steaks? If you tip the cops we'll hang him up on one of your meat-hooks to cure."

THE picket lay outstretched on the floor in Doc's

back-room and he was a pitiful thing, all the savagery hammered out of

him with the pounding out of consciousness. A blue, terrifying

blotch on his sallow temple was the mark placed on him by

Klingel's blow and breath caught in Andrew Turner's throat as he

saw it. He bent to him, snatched at the scrawny wrist, sought for

the pulse with trembling fingertips.

It was there, a sluggish beat, beat, beat. Doc's face cleared. He lifted, searched on a shelf for a tiny bottle stoppered with a thin membrane of red rubber, rummaged in a drawer for a gleaming hypodermic syringe. The scratch of a match was loud in the odd, brittle hush that somehow set the cluttered back-room apart from the bustle of the busy street outside, and a blue flame danced atop a tiny alcohol lamp as the pharmacist sterilized the silvery, hollow needle of the instrument he had brought forth for some esoteric ritual he contemplated.

The tan-coated man gurgled, far back in his throat. Doc twisted to him, saw a long quiver run through the recumbent, famished frame. Heavy footfalls thudded from beyond the partition, and a burly, squat youth thrust through the curtained doorway.

"What's up?" Jack Ransom blurted. His auburn mop of hair made a bright spot in the dimness and the grease-daubed overalls he wore could not conceal the strength in his husky frame, the ripple of his flat, powerful muscles. "Abie says there's hell to pay."

"Hell and the devil himself. Hold that bird in case he comes to while I'm giving him a shot of this stuff." Turner had stabbed the hypodermic needle through the rubber closure of the vial, was drawing the limpid liquid it contained up into the graduated glass barrel of the syringe. Ransom went to his knees alongside the reviving man, clamped steel-like fingers on the fellow's shoulders, holding him down. "But we'll pay him in coin he won't like if this works as it should," Doc finished as he too went down on his knees.

"Something to do with Klingel, I would gather," Jack prodded, watching as the pharmacist shoved up the tan coat-sleeve to bare a painfully thin forearm. Coat-sleeve alone, the man wore neither jacket nor topshirt under it.

"With Klingel and with all the poor dubs around here who can just about manage to keep from starving with the cost of food as high as it is." Turner dabbed a bit of skin with iodine, just where a blue vein showed wormlike beneath. "The man got a sweet little note and our Abie wangled it out of him." The needle slid, sickeningly, into the vein, and Doc pressed on the syringe plunger, forcing the mysterious liquid into the fellow's circulation. The unwilling patient squealed out of his sleep, tried to writhe against Ransom's immobilizing grip.

Withdrawing the needle, watching the picket with narrowed eyes, Turner repeated the leering, cruel sentences. "You get the set-up, Jack," he went on, soft-voiced. "Klingel signs up to save little Carl; the rest of the food sellers follow suit, brought to heel because their leader is licked. Prices go up to meet the payments to the racketeers—and Morris Street starves."

"It's damn near to starving now. But what's the good of monkeying with this bird? Why don't you tell Klingel to settle, and when they come around to get his signature we can follow them..."

"No good. They're too cagey for that. If they weren't, the note would have given him instructions. They've jabbed him, and they're watching which way he'll jump. If he'd gone to the cops it would have been just too bad for Carl. They're shrewd and they won't be caught in any ordinary trap. Our only chance to save the kid and bust them up is to make this chap talk before his friends make their next move."

"Talk! He won't talk. He's just a hanger-on but he knows he'll get a knife in his gizzard if he does any tattling. He'll play dumb or he'll lie..."

"He'll talk and he won't lie." Grimly. "I—but he's coming awake!"

THE picket's yellow eyelids fluttered, came open. He stared up

into Ransom's freckled countenance. His look shifted to Doc's

bleak, white-mustached face. Terror sprang into his blood-shot,

colorless-pupilled eyes and his livid lips twisted to emit a

jibber of thin fear.

"Le'me go," he squealed, struggling weakly. "Le'me go or..."

"It's all right," Turner spoke softly, soothingly. "It's all right. We're your friends. We're taking care of you. Lie still for a minute and you'll be all right." There was no excitement in his accents, there was only a sort of mild insistence. "You believe that we are your friends and you want to help us."

The fellow relaxed, the tight quiver of tiny muscles in his face smoothing to lines of ease, the terror fading from his expression and leaving only a half-dazed wonder and a waiting acquiescence somehow macabre.

"That's better," Turner's monotone continued. "That's better—what's your name?"

"Dan." He mimicked Doc's smooth, casual tones. "Dan Siles."

"Dan, you're going to tell us something. You're going to tell us where Carl Klingel is. The little boy they snatched this afternoon, coming from school. Where did they take him, Dan?"

Siles looked troubled. "I—I don't know. I don't know."

"I told you so," Jack spluttered. "Let me knock it out..."

"Shut up, you fool," Doc snapped. Then, to the picket: "You don't know about Carl. Are you sure?"

"Sure."

"Then tell us who hired you to walk picket in front of the butcher shop. Who taught you how to do it?"

Intelligence came back into the bleared eyes. "Gorton. Gimpy Gorton. I didn't want to work for the crook but it was take his filthy jobs or starve."

Doc flashed a look of triumph at Ransom. "And where can I find Gimpy? Where does he hang out?"

"Three eleven Loring Avenue. The old Armour branch meat-dressing house.—I'm tired. I want to sleep."

"Sure you can sleep. Look. We'll make a bed for you on the counter right here. Jack, put some coats on the counter and make it soft for our friend Dan. Use the cushion from my deck chair for a pillow. We're going places and doing things."

Siles was already asleep when Ransom lifted him to the counter. "You gave him some dope," he grunted. "But I don't get the rest of it. I don't get what made him talk, if he isn't handing us a line that's sending us on a wild-goose chase."

"There was more than morphine in that injection, son. There was something that made it impossible for him to lie. Scopolamine, the truth-drug. Using it in an obstetrical case. Dr. R. E. House of Texas discovered that scopolamine dulls the inhibitions, under its influence a man cannot lie. Dr. Calvin Goddard, the eminent criminologist, developed its use in investigations of crime, and its efficacy was proved in the solution of a mass-murder mystery in Birmingham. It's infallible."

The ginger-headed youth's eyes glowed with excitement. "Swell! But what are we waiting for? Let's get going."

"We are going, but we're not going off half-cocked. We're dealing with a gang of ruthless, clever men, and a little boy's life depends on our not making any misstep. Listen, here's what we'll do."

LORING AVENUE lies at right angles to the River, a

two-block long alley lined with platform-fronted warehouses into

which meats and fruits and vegetables flow from ranch and orchard

and farm to feed the great, sprawling, ever-hungry city. A

battered flivver rocked along its cobbled length in momentary

peril of being demolished by huge, lumbering trucks whose

red-faced, jutting-jawed chauffeurs drove their behemoths with utter

disregard of any smaller fry that might scutter under their

wheels.

"There's three-eleven," Jack Ransom grunted, twisting his wheel to bring the decrepit sedan alongside a loading platform, behind which a wood-fronted, tottering structure was squeezed between two modern brick warehouses. "Riverside Provisions the sign says, and it's new. Looks like something more to the scheme than the Clerk Union racket." A gray ulster had replaced his overalls, and a hard, black derby was canted over one ear at the exact slant prescribed by custom for a political heeler.

"Yes," Doc's frail figure seemed frailer still, enveloped in a black overcoat two sizes too large for him, broad brimmed fedora pulled low over his forehead. Frail and insignificant. It would be Jack's aggressive personality that would monopolize attention. "After they get their hooks on their intended victims they'll sell them their stock too, rotten tripe at fancy prices. But they're not doing business yet."

"Not that kind of business anyway." The platform was empty and deserted, the paintless door in the shuttered front blind and furtive. Ransom braked, followed Turner up the splintered steps that led to it. "Guess they're not looking for customers just yet."

Jack tried the door. It resisted his twist at the knob. His knuckles thumped on the wood, loud and authoritative.

Footsteps shambled within. Metal slid gratingly, and there was suddenly a hole in drab panel through which a single, glittering eye leered. "Not open yet, mister," a muffled voice rumbled.

"You're open for us," Jack twitched the flap of his ulster aside, displaying a gold badge for a fleeting instant. "We're Federal men. Agricultural Adjustment Administration."

"Wait a minute."

The metal shield clicked shut over the peephole, the footsteps shambled away.

"Cagey is right," Ransom muttered from the side of his mouth. "But I think he fell for it."

"We'll get in. But then..." Sharp sound cut Doc off, the rattle of a bolt sliding out of its socket. The door creaked open, shut daylight out behind them...

A PENDANT, unshaded bulb shed a grimy light that brought

out clearly a tottering desk bare except for a telephone, and was

lost in the brooding-shadows of a vast, gloomy interior. The man

who had opened the door was ape-shouldered, low-browed,

brute-jawed, but the one seated at the desk, swung half around to face

them, was of another breed. Slender, dapper, there was a

ferretlike venom in his weazened body, reptilian cruelty in his

cold eyes, in his lips that were a straight, thin gash across the

immobility of his pointed countenance. Something queer, too,

about the way his left leg stuck straight out from his chair. It

was jointless, its knee immobilized by some long-ago

accident—or bone-shattering bullet. This, Doc thought, is

certainly. "Gimpy" Gorton.

"Well, what do you want?" Gorton's lips seemed to move not at all but the question must have come from him. "What's the big idea?"

Jack shouldered forward. "We've got a report you're receiving bootleg potatoes. You know the law. We're making an inspection."

Turner wandered aimlessly past the desk. The light's glare behind him, he could make out a barn-like room. Long wooden bars were suspended from the high ceiling, studded by sharp-pointed hooks like those in Klingel's window and at the rear, the slatted wall of a huge refrigerator loomed, its door fastened shut by a huge throw-bar. A pulse throbbed in his wrists when he saw that.

Gorton laughed shortly. "There's nothing here to inspect. We're just starting business and you can see for yourself nothing's been delivered yet." His left hand waved toward the vacant floor but his right hand hovered near, very near his lapel. "Someone's having a little fun with you boys."

Jack grinned. "Looks like it. But we might as well take a look around long as we're here."

"Where you goin'?" The gorilla-like doorman came up behind Doc, put a hamlike hand on his shoulder. "Where you think you're going?"

The old druggist turned, peered nearsightedly into the other's unshaven face, his hand sliding into his overcoat pocket. "This is the old Armour plant, isn't it?" he quavered uncertainly. "Where they used to dress their beef before they put up the new building next door. Left their icebox didn't they?"

"What's that to you?" the fellow now growled, licking thick lips. "You're gettin' too damn nosey."

"Careful, Hen." Gorton had seemed absorbed in his talk with Jack but he flung the sharp bark over his shoulder as though he had eyes and ears in the back of his head. "We've got to treat Uncle Sam with proper respect."

"Yeah but..."

"That will do. These gentlemen are entitled to look at anything they want to, and ask any questions they want. You come back here and let that man alone."

Doc's heart sank. Was he wrong after all? Was the icebox as empty as the rest of the place? His visage an expressionless false-face, he started forward again, making straight for the refrigerator. There would be no need, yet, for his gun.

"Look here, mister inspector." Gorton's tones came clearly to him. "There's nothing here now to interest you but—" they slowed, became meaningful—"there may be later. I've got five hundred dollars that says you and your partner are going out of here now and are never coming back."

"That's interesting," Jack responded. "That's very interesting." He leaned forward, putting both hands on the desk, the muscles in his calves tightening for a spring. "What's it supposed to pay for?"

DOC reached the big icebox. His hand went out, closed on

the big bar that held it shut. If the box was empty, where did

they hold Carl prisoner? It must be empty or they wouldn't be

letting him—

"You know damn well what it's supposed to pay for," Gorton snarled. "But you're not getting it." Doc swung the barrier over, clawed at the open-topped socket in which it had rested to pull the portal toward him. The big leaf started to swing, a frightened little cry came out of the widening slit. Jack heard it, and grabbed Gorton's right wrist.

"Take him, Joe!" the weasel-faced man barked, and his left hand darted out of his pocket, lengthened suddenly by a whistling blackjack that thumped viciously on Ransom's biceps, paralyzing them.

Hen lunged forward, got his big paws inside the crooks of Jack's elbows, jerked them backwards and together behind his back. At Gorton's cry a black figure had lurched out of a dark recess between the icebox and the sidewall, was catapulting toward Doc. The old man now whipped around, fingers plunging into the side-pocket of his coat, frantically grabbing for his revolver. A fist flailed against his chin and darkness exploded in his brain.

ANDREW TURNER weltered out of oblivion, pain pounding within his old skull, sick nausea twisting at his stomach. A child's voice whimpered, somewhere in the whirling vertigo, and someone was breathing heavily. Doc opened his eyes.

Light glared down into them, needled them with red-hot prickles of pain. They cleared and he saw that he was recumbent on the floor inside of the big meat box, wooden bars over him bristling with the curved hooks to which shreds of rot-blackened gristle still clung. Jack was on his haunches in a corner, arms lashed behind his back, ankles bound together. Next to him was the shuddering form of a ten-year-old boy, round-faced, blond and blue-eyed. Gorton stood above the two, smiling evilly, and Hen and Joe, like enough to be twins, flanked him.

A butcher's block centered the refrigerator, and the point of a big knife caught the light, projecting out over its edge. "Thought you were kidding me, eh, you and the old fool?" Gorton lipped. "You didn't know there ain't no potato inspection been started but I did. I picked you for phonies when you pulled that but I let you play around till I made sure what your game was. Come lookin' for the brat, did you? Well you found him. How do you like it?"

Doc's eyes flickered closed. They hadn't noticed that he had come awake and they hadn't tied him. They didn't figure an old man was good for anything.

"I like it." Jack spoke through clenched teeth, but his voice didn't shake. "Your jig's up and you know it. We didn't come here without leaving word where we were going. The cops will be here if we don't show up in half an hour and you'll be through."

"You're not cops and you haven't tipped off the cops. I've got the precinct house and headquarters both covered in case Klingel got funny. You came in here alone and you're going out alone, in pieces. Hen's a swell butcher and he's going to work on the brat first, with the knife and cleaver that's on that block."

THE sinister meaning of the man's threat pronged Doc,

wrenched a groan from him. "He's comin' out of it," someone

exclaimed and the old man knew it was now or never. He rolled

over, threshing as if in spasmodic recovery from the coma into

which Joe's knockout blow had sent him. His knees were under him,

his hands thrust against the floor and he exploded to his feet,

alongside the block for which that roll had been aimed. In the

same motion, it seemed, knife and cleaver were in his grasp.

The boy screamed and the heavy cleaver left Doc's fingers. Its sharp edge crunched into Hen's face, and then there was no face there any longer—only a red horror. Joe roared, plunged at the little druggist, a blackjack flailing ahead of him. A gun was suddenly in Gorton's hand, flipped from its holster, was snouting at Doc.

Jack threw himself bodily at the weazened mobster. His head butted into Gorton's midriff and the jetting, orange flare from the automatic lashed harmlessly into the icebox wall. Doc dodged the blackjack's lethal swoop, went in under Joe's columnar arms and sank the long carving knife to its hilt in the fellow's breast. The thunder of another shot from Gorton's gun beat against his ear-drums, Jack shouted, and Turner jerked his weapon out of the flesh which had sheathed it.

A spurt of scarlet sprayed out of the gaping wound. The gangster collapsed like a ripped meal sack and Doc whirled. Gorton had kicked Ransom away from him, was setting himself for another shot at the little druggist who so suddenly had become a whirling dervish of fatal fury. There was ten feet between them, ten clear feet. Doc couldn't get to him in time to stop that shot and he was a clear, unmissable target.

Gorton's trigger hand showed white at the knuckles now as it tightened. Carl screamed, was on the mobster, a kicking, scratching small bundle of hysteric attack. The gun thundered and the little fellow jolted away from the man, hurled away by the tearing lead. But Doc had leaped across the intervening space. It was into a pulsant throat that his knife sliced.

He let it stay where it was, spun around to look for Carl. The blond youngster was a crumpled pathetic heap in the shambles of that icebox. Doc went to his knees alongside the lad, gasped when he saw the stain spreading on the tiny jacket. His gnarled fingers tore at the little suit.

"God, Doc," Jack gasped from the corner where he lay. "The tike had guts, I hope..."

"It's all right." Andrew Turner's voice was for once a shrill almost mindless thing. "The bullet got him in the shoulder. Broke his collarbone, but he'll be all right when it heals."

EVEN Doc's commands could not control the mob that surged

around the battered flivver as it drew up in front of Klingel's

shop with its blood-spattered, wild-eyed passengers. But they

made a path for the silver-haired, age-stooped little druggist

who seemed too feeble to carry the white-faced, limp form he bore

in his arms. The butcher's door opened, this time, and a plump,

ample-bosomed woman ran out.

"Mein Carl!" she screamed. "Ach, mein Carl. He is tot, dead!"

"No," Doc murmured, staggering past her, through the clean-swept store to the garnished room beyond. "No. But he's got a broken shoulder that needs a doctor." He laid the little fellow on a couch. "Where's Otto?"

"Here I am, mein friend." The obese German loomed over him. "Ach, vot a friend. How can I efer thank you? Vot can I do...?"

"I'll tell you," Doc turned to him. "You can hire an errand boy at ten dollars a week. That won't break you or force you to raise your prices."

Klingel blinked small eyes. "Ach, for shoor. Aber—but who?"

"A chap named Dan Siles. You know him. You've seen a lot of him recently—too much. The man who has been picketing in front of your store."

Fat wattles shook with homeric laughter. "A joker you are. Such a joker!"

"No, Otto, I'm not joking. If it wasn't for Dan Siles your boy wouldn't be here."

"But he wass one from die Teufel, the devils, vot haff so nearly killt mein Carl, vot haff nearly ruined Morris Street!"

"He was one of them because hunger drove him to it. Hunger and nakedness, Otto. You with your fat belly have never known how hunger can tear at your vitals and drive you mad. Mad as a different anguish was driving you not an hour ago. You're going to see to it that Dan Siles never knows that anguish again."