RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

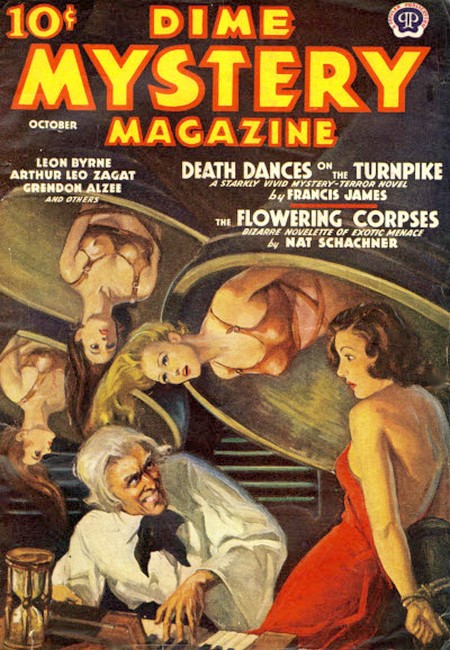

Dime Mystery Magazine, October 1938, with "The Brothers From Hell"

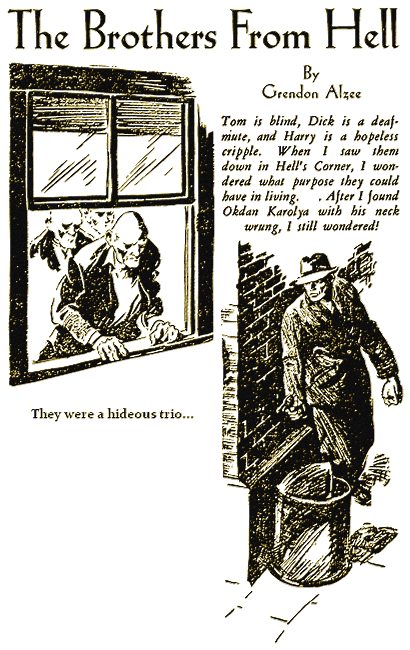

TOM is blind, Dick is a deaf mute, and Harry's is a hopeless cripple. When I saw them down in Hell's Corner, I wondered what purpose they could have in living. After I found Okdan Karolya with his neck wrung, I still wondered!

TOM is blind, Dick is a deaf mute, and Harry's legs are so grotesquely twisted that he cannot walk. They are a weird trio. The denizens of Hell's Corner touch iron, or point the finger-horns that are reputedly effective against the Evil Eye, whenever they see Dick or Tom in the crooked, stinking alleys of their neighborhood. Harry is never in the streets.

Okdan Karolya, the cross-eyed hunchback who ran the gin-mill at the corner of Pig Lane and Third, and looked after the tenements around there, was the first to see any of them. I got the story from Okdan, first hand. I would like to repeat it in his words, but his speech is beyond my power to reproduce.

Here, however, is the gist of what he told me:

The Corner awakes only after dark, and midnight is its high noon. At four a.m. they scuttle back into their crannies. At about four-twenty on this particular morning, Karolya's dive was empty except for a bum sprawled over a table, stubbled cheek flat in a pool of stale beer.

Okdan finished counting his night's take and yawned. Coming around the end of the bar, he hobbled across his floor of sodden, rancid sawdust, intent on evicting the sleeper.

But the drunk was not to be disturbed just yet.

A rattle of the doorknob halted Okdan. He turned to the sound, wondering what profit there would be for him in the belated visit. Many and curious flies came to the hunchback's cobweb.

There was glass in the frame of the door, but this was too crusted with dirt to permit Karolya to see through it anything more than a formless blur. It opened slowly. This raised Okdan's hopes. He threw a furtive glance at the drunk to make certain this sleep was genuine, and at the same time put a hand into the pocket of his apron. There was an automatic in that pocket. Okdan Karolya put no trust in banks, and took no chances on anyone's becoming unduly curious about where he hid his hoard.

When he again faced the door, Karolya's throat went dry and he pulled in a sharp, shocked breath. Hardly anyone came to that joint of his who was not corrupt in body and face as well as soul, but there was something about the man who stood gaunt and tall in his doorway.

It wasn't the ankle-long, threadbare cape he held wrapped about himself, or the strange black hat he wore, flat-crowned and wide-brimmed and greenish with age, though these were discomforting enough. It was not altogether his countenance, though this was not so much a face as a mask of collodion, glistening and tightly stretched over flesh the color of putty; a mask without beard or eyelash or brow. It was his grin. That grin was not a smile, but two livid scars which lengthened the grim gash that was his mouth.

And too, there was the still, expectant way the man stood there. "Lak he see sometinks in here gonna jump on me," Karolya said, his red-rimmed left eye ogling a far corner, while the right canted up to the ceiling. "Sometinks nobody got a right to see."

So definite was his impression that the newcomer watched some horror behind him, that Okdan looked apprehensively over his lower shoulder. The worst thing he saw was his own dwarfed and crooked reflection in the cracked mirror behind the bar. He got hold of himself and demanded what the man wanted.

The scarred mouth came open, emitting an inhuman sound. Karolya saw that the tongue, behind toothless gums, was nothing but a wisp of shrivelled flesh.

Hands came out from within the rusty folds of the cape, chalk-white hands whose fingers were much too slender and much too long. The hands made gestures so expressive that the hunchback had no difficulty in comprehending that his visitor was concerned with a cellar, a cellar down the block, three houses down the block.

There was a vacant space in that cellar. A sign offered it to rent, and for a new tenant to show up at this hour was the usual course of events in the Hell's Corner. Okdan asked whether the mute wished the room. Reading his lips, the fellow pantomined assent. He was told that the charge would be five dollars a month, in advance.

The hands writhed back within the cape. One of them emerged again with five bright silver dollars, their milling still sharp.

Now in our section of the country we seldom see silver dollars, and the fact the man offered them heightened Karolya's feeling of his eeriness. But it was money, and the cellar had been vacant a month. Okdan took the coins and, to make sure they were genuine, rang each one separately on the bar. That made noise enough to wake the drunk. He suddenly vented a gurgling scream and came lunging past the dive-keeper.

Okdan was of the opinion that the bum was merely frightened out of what little wits he had by the ghastly apparition in the doorway, and was making a break for the open. But the mute evidently thought differently, for his hands flashed out of the cape. They clamped on the screaming man's throat and lifted his hundred and sixty pounds of whiskey-filled hulk a foot off the floor; held it there at arm's length!

Those pallid fingers, so long that their tips lapped over an inch at the back of the throttled neck, must have done something to their victim's spine. The bum hung from them, left leg convulsively drawn up, dirt-crusted hands twitching. He was making no struggle to fight that strangling clutch.

On the mute's glistening countenance there was no expression but that meaningless grin.

Okdan Karolya didn't give a hoot in hell whether the choking man lived or died, but if he died in there it would mean trouble, one way or another, and Karolya didn't like trouble unless he was paid for it. So the automatic came out of his apron and its muzzle prodded the mute's side while Okdan made signs for him to let go.

He might as well have made signs to the lewdly amended chromo of a nude on the wall for all the effect they had.

The bum's face was so purple the stubble on it didn't show any more, and his eyeballs seemed about to drop out of their sockets. Karolya would cheerfully have squeezed his trigger, but that would simply make more trouble without profit.

It was at that instant that Mary came through the door in the partition behind the bar and stopped there, her hand going to her breast, her pupils dilating.

That must have been a picture to challenge Doré: The dim, foul room with its low, fly-specked ceiling, its floor of sawdust stained with tobacco juice, liquor and mud; its rows of round, leprous tables, five gleaming silver dollars strewn over one of them. The spectral apparition and the paralyzed drunk hanging from his clutch. Okdan, twisted, dwarfed, swarthy; his thick lips twitching; his mis-mated eyes staring everywhere but at that at which he looked.

And for a highlight, there was Mary behind the bar, in a blue satin kimono hastily thrown over a gossamer nightgown that hardly veiled the glimmering sheen of her slender body. Raven hair cascading over perfect shoulders to set off the transparent glow of her lovely face.

It may be even more revolting to know that Mary, who is beautiful as a drug-taker's dream of an angel, was the hunchback's wife!

THE scene held like that, utterly without motion, for the

space of two heartbeats. When the third pulse throbbed in the

curve of Mary Karolya's throat, the drunk thudded to the sawdust,

a crumpled heap. The mute went backward out of the dive, and

Okdan bent to see if he had a corpse on his hands.

The man was alive. Karolya forced a fiery draught between his teeth. The bum scrambled, sputtering, to his feet and lurched out. It is doubtful whether he had any recollection at all of what had occurred, but the white, ridged weals around his neck must have taken days to disappear.

The hunchback made sure the door was double-locked before he let Mary explain that she had been awakened, in their living quarters above the saloon, by a premonition of peril. It was so strong that it pulled her, almost without conscious volition, out of her bed and into the bar-room.

Neither could explain why her coming had saved the life of the drunk, but neither doubted that it had.

ALL this Okdan Karolya told me late the next day, when I went

to him to ask about the three newcomers. We let the evil of

Hell's Corner flourish pretty much as it pleases, except that we

try to hold the killings within reasonable limits. In order to

keep things in check, we keep as close a watch on the denizens of

the place. This would be more difficult than it is, were it not

for a few people like Karolya, who exchange for certain favors

from the police the information we require.

Something more than duty, though, inspired the curiosity that took me to Okdan's that day. I had just seen the three moving into the cellar he had rented them.

I had been following up an inquiry from the Bureau of Missing Persons, about someone whose last known address was Pig Lane. Learning nothing, as I expected, I emerged from a stinking hallway and came face to face with an unforgettable procession.

The Lane is about fifteen feet wide. The wooden walls of the houses that line it lean drunkenly toward each other, and they seem tied together by ropes from which hang grey banners of tattered washing. As a result of these facts, a sort of perpetual twilight lives in the cobbled, garbage-strewn gutter below.

Through this grey dusk rattled a huge pushcart. Harnessed to the front of it by an intricate arrangement of cording was the deaf-mute I have described the way Okdan Karolya saw him the night before. Another caped individual shoved the cart by its handles. He was as tall and gaunt as the first, displayed the same grotesque grin on his glistening, lashless mask. Lashless? He had no need of eyelashes, for where eyes should be there were only empty sockets, blackened holes that might have been seared into his putty-colored countenance by a soldering iron.

The wagon itself was piled with bundles, some wrapped in heavy paper, some composed of bulging, knotted sheets. Atop these, jolting and swaying with the jolting and swaying of the two-wheeled vehicle, squatted the third of the trio.

He gripped the legs of an up-ended table with chalk-white hands, to keep from being thrown off, and so his cape was held open. His torso was barrel-chested, powerful, but below the waist there were legs too small to have served a seven-year old child, legs corkscrewed so that the toe of the left foot pointed in the opposite direction from that of the right, and neither in the way they should have pointed.

The man in front could not hear or speak, but he could lead the way. The man in back could not see, but his strength kept the cart rolling. The man in the cart could see and hear and speak, but he was excess baggage, no less a burden for the others than the bundles and furniture upon which he squatted.

THE sight stopped me, held me goggle-eyed till they went past.

It was their grins, those damned grins that were carved into

their faces, that was the worst of them. Their grins, and the

awful black pits in the blind one's head.

Before I could think what to do about them, or whether I should do anything at all, the leader swerved to the maw of a cellar entrance next door. The cripple called a direction. The sightless one acknowledged it, and maneuvered the cart in line with the entrance. The pushcart bumped down into the cellar.

The first thing for which I asked Karolya, when I got to his place, was the special bottle he keeps under the counter for me. After I'd taken a hearty swig from that, I inquired about his three new tenants.

"T'ree," he exclaimed. "T'ree? I see only yun." And then he gave me the story of the night before. His maimed syllables fell over themselves, spilling from his protruding lips as if all day he had been avid to talk about the thing, and had dared not. "Mary do not sleep," he ended. "Alla night she valk, valk, valk de floor."

"I don't blame her," I commented, wondering for the fiftieth time at the strange, gloating sort of triumph that came into that ape's visage of his at the mention of his wife, wondering for the hundredth time where she had come from and how he had prevailed on her to come to him.

She had appeared there one day, about a year before and remained. She never went out. She never spoke to anyone. And he never explained her. "I'll probably have nightmares myself after what I've seen of them."

He reminded me that I hadn't told him what I'd seen. "Three brothers from Hell," I answered, and taking another drink to burn away the recollection, I told him.

This talking about them and, I imagine, the whiskey, made me aware that there was no good reason for my agitation. "They're queer looking ducks," I wound up. "But I don't suppose they like their looks any better than I do. After all, there's something admirable about their sticking together and taking care of one another." I chuckled. "Tom, Dick and Harry. I got those names in that interchange at the cellar entrance, but I'd be willing to bet they weren't baptised with them. Tom is the blind one, Dick the deaf mute, and Harry the one who can't walk."

THE first of the evening's customers came in just then and I

moved out. Part of our tacit agreement, Okdan's and mine, was

that I should not hang around there. It was bad for his kind of

trade to have detectives too much in evidence.

I changed tours a couple of nights later, so after working the four to twelve, I started right in on the twelve to eight. Things were pretty quiet for the Corner. There were the usual number of street brawls for the patrolmen to break up and the usual two or three knifings, but nothing that called for any work from me or the other two precinct detectives. A financial stringency kept me out of the backroom poker game, and I couldn't sleep for the yowling of the drunks in the cells downstairs. Along about four-thirty the desk lieutenant decided it might be a good idea if someone took a walk around the district and put it to bed.

Pat Garrity doesn't take kindly to the idea of college men on the force. He picked on me for that promenade, and I had a pretty good hunch he wouldn't be over-perturbed if it ended for me with a few inches of steel in my back. I may be wrong, of course, but otherwise, why would he send me out alone, when even the uniformed men work night tours in Hell's-Corner in pairs?

IT was muggy out, with a low ceiling of cloud and no breeze,

so the stench was particularly bad. After a half hour of it I

needed a drink badly, to settle my stomach. I made for Karolya's

to get one, hoping that his dive would still be open.

It wasn't. At least it showed no light when I got to it. But I rattled the door anyway, with the thought that he might hear me. Right then a glow of light wavered across the dirty glass and lay against it.

That's queer, I thought. It's not one of his ceiling bulbs, it's a flashlight. I put my face close to the pane, trying to peer in. The light got brighter, and then a hand inside rubbed a clear spot in the grime. It was slim and white. A woman's hand.

I could see through now. I saw Mary Karolya. She had nothing on but a nightgown, but there was a flashlight in her hand. Her lips were white and her eyes staring. She was terrified.

"Open up," I yelled. "Open the door."

The torch was quivering, but she managed to keep its light on my face. I saw her lips form the words, "Who are you?" I turned the lapel of my jacket to uncover my badge and moved so that she could see it through the clear spot. Then I yelled, "Open up," once more.

Her voice came very faintly to me. "Break the glass."

I couldn't understand that, but I had to get in and there was nothing else to do. I used the butt of my gun to smash the glass out of the door. As the first fragments crashed in, something silvery whizzed down and up again so fast that I couldn't see what it was. But there was a fresh gash in the floor, as though someone had chopped it with a knife.

"Watch out," the woman said. "Keep away from the sides of the door as you come in." I didn't need her warning. I'd already seen that the door was a death trap for anyone who tried to open it, without knowing exactly how, when it was set.

I went through without getting caught. "What's up?" I demanded. "Where's Okdan?"

"Come," she whispered, already turning. I wanted to pick her up and carry her, so that her bare little feet wouldn't have to walk through the muck on that floor, but of course I didn't suggest it. I followed her behind the bar and through the door at the back of it.

She clicked off the flash. There was dim light from somewhere and her misty form was wraithlike in its glow.

She led me up a flight of stairs. The light was stronger up there and I saw that we were passing through a living room as clean and well furnished as any I've ever been in. Then we went through another door into the room from which the light came. I knew it was a bedroom, though I wasn't aware of any of its furnishings. I saw only that at which the woman, abruptly motionless, pointed. Okdan Karolya. A gargoylesque heap on the rug.

HE was dead. No question of that. No man could be alive with

his head twisted around like that, so that his unshaven chin

nuzzled the hump on his back. With his head wrung like a

chicken's.

"Who did that?" I gasped.

"I don't know," Mary Karolya whispered.

"But you were here, in the room."

"Yes. I think it must have been the sound of his falling that woke me up. I saw"—her pointing finger jerked to an open window—"the shadow of a head. And hands—fingers—writhing—dropping from the sill."

"Hands," I repeated inanely. If I remembered rightly, that window was ten feet above the pavement, and there was no foothold on the brick wall. I started for the opening.

She grabbed my arm. "Don't go near it!" she cried.

"Why not?"

"Look." She shoved a chair toward it. It reached a foot from the wall and something flashed down across the sash. It chunked into the chair-top, bit a two-inch gash in the wood and was held by it. It was a blade of curved steel eighteen inches long. A machete. Its long wooden handle slanted down from a boxlike contrivance above the top of the sash. I felt sick, realizing what my skull would have been like if I had stepped on the floor-board where the chair foot rested.

"Every window in the house is fixed like that," Mary Karolya whispered, "and the two outer doors. To keep burglars out—and me in." The last was a mere shadow of sound.

I wheeled, ran out through the living room, down the stairs, out into the bar-room. I had heard the faint thud of running footfalls outside, had guessed they belonged to a cop who'd heard the glass smashing.

"Stop there," I yelled. "Don't touch that door!"

Hank Clancy goggled at me through the jagged opening, club and gun out. Jim Forbes came up beside him.

I explained. Then I sent Forbes to phone the station house. "Tell Garrity we'll need the Emergency Squad as well as Homicide," I said. "They've got to fix things so some blundering ass doesn't get killed. Clancy, you stay here. This is the only way anyone can get out." I ran back, ran upstairs. Mary Karolya was still in the bedroom, statuesque, staring down at that grotesque horror on the floor.

"Get some clothes on!" I commanded her from the door. "Touch as little in that room as you can help. Then come downstairs."

I went downstairs again, and out. Forbes was back and I gestured him to come with me. We went down Pig Lane, three doors and turned into the cellar there. I had my gat and my flashlight in my hands when I pushed open the unlocked door in the board partition that blocked off the room Okdan Karolya had rented for five silver dollars.

Snores greeted me. I thumbed my torch, tilting it so that its beam would hit the ceiling and I would see the room by reflected light. That place was clean as a whistle, those three must have worked like beavers to make it so. The only furniture was a table and two chairs I recalled seeing on the pushcart. Three beds were made up on the floor, and they were all occupied.

The form in the end pallet stirred, and sat up. It was Harry, the cripple. His eyes blinked open and stared at me without surprise.

"What do you want here?"

"Which one of you three just came in?"

"And who are you to ask that?"

"Police, mister." I showed my badge. "Now answer me."

"Certainly." The other two were stirring now, wakened by our talk, but it was Harry who replied. "It's none of your business, police or not."

"No? Maybe we'll make it our business. In the meantime, you're staying here. Forbes!" I turned to the cop. "You stand at this door and see that they stay put. Keep your gun out and don't let any of them get within three feet of you." I was thinking of hands. Of the hands Mary had seen vanishing through the window. Of the hands Okdan had seen lift a hundred and sixty pounds and hold them at arms' length.

WHEN I got back to the corner the big Emergency Squad wagon

was there, surrounded by a shoving crowd.

Inside the house the boys were busy rendering Karolya's death-traps harmless. They confirmed Mary's statement. No one could have gotten into the place or out of it with a whole skull. Her eyes were on me while I asked about that.

The Homicide Squad trampled in, followed by the medical examiner. I told them as much as I knew, and went out again, to the areaway behind the house on which the window of the death room looked. I confirmed my recollection of its height above the ground. Ten feet. Only a fly could have climbed that wall. A ladder? Possibly. The concrete paving was too dry to show marks. But Okdan lay a full four feet from the window. No one could have reached him from a ladder at the sill. No one could have gotten, alive, into the room, to reach him. Perhaps he had been undressing nearer the window, and had been thrown to where he lay.

He hadn't. The experts of the squad established that. The rug on that floor was a high-piled, silky Persian. Its nap held footmarks for a long time. They traced Karolya's movements with precision, from the moment he had entered to retire. They showed that he'd never been within three feet of the window.

They showed also that no one had been in the room that night beside the murdered man, his wife, and myself.

There were no unaccounted-for fingerprints on the sill or the sash. There were no signs on the outside of the sill of a ladder having leaned against it, and its wood was too decayed not to have taken such signs. There was absolutely nothing to show that the Karolyas had not been alone there when Okdan had died.

The medical examiner found a bruise on the side of the cadaver's chin, another on his shoulder, in exactly the right spots for the leverage required to wring its neck. The doctor stated unequivocally that Mary could not possibly have a tenth the strength to do it.

Captain Ryan of Homicide ordered her arrested anyway. We had to arrest someone, and we couldn't touch the men I had set Forbes to guard. There wasn't a scrap of evidence to connect them with the crime.

When I went to call Jim Forbes out of the cellar, the three were asleep again. On the pillows their heads didn't look like human heads at all. They looked like the heads of some statues I've seen at the Museum of Natural History.

AFTER Mary Karolya had been grilled for eighteen hours, the

district attorney ordered her release. He said no jury ever

assembled would convict her with the facts he could present.

I went around that night to talk to her. She wasn't in the house on Pig Lane. The cop we'd left on guard said she'd returned there, had gone out again in half an hour, carrying a single battered suitcase. It wasn't hard to find the driver of the taxi she had taken. He'd brought her to the railroad station. I located the booth where she'd bought her ticket. It was to Chicago, and she'd paid for it with silver dollars. With twenty-three silver dollars, brand-new and shining!

I had no right to wire Chicago to have her trailed. There was no charge against her.

I WENT back to Pig Lane. The house wasn't empty any longer.

Men from Homicide were there, and the boys from Emergency.

Captain Ryan had hit upon the bright idea that there must be a

secret entrance to the house. He'd ordered the place ripped to

pieces to find it.

They did exactly that, thoroughly. They didn't find any passages. But they did find Karolya's cache, a steel vault concealed between the floor of his living room and the ceiling of the one beneath, its opening ingeniously contrived.

It was jammed full with wealth. A lot of this was in bonds listed as stolen, bills whose numbers identified them as being some of the ransom paid out for the Kelton kid, and more stuff like that. But there were a good many thousands in cash that could have been spent anywhere, by anyone, without trouble. It had been there for the taking and Mary'd not touched a penny of it.

They found something else of interest. A crumpled letter that somehow had slipped into a crack in the dresser in the bedroom. It had a faint smell of perfume about it. It read this way:

Dear Sis:

I know you must have been nuts with worrying, not hearing from me for six months, but there wasn't no way I could reach you without the cops tracing back to me, and I knew you'd rather worry about me than know I was nabbed and booked for the hot seat. Once they caught me it would be that, and no out.

I'm pretty near nuts myself, dodging around the country. Pretty near nuts and dead broke. Couple days ago I was ready to chuck in my cards and take what was coming to me, that's how bad it was. And then I got a break. I got wind of a guy that makes a business of getting blokes like me out of their jams, and I managed to get to him.

Guess who it is. Remember that hunchback kid used to live across the tracks? Okdan Karolya? We were pretty lousy to him in them days, but he's all right. He's going to take care of me, even if I ain't got nothing to pay him with. He's going to ship me out to South America, to a place where there ain't no extradition. That is, he will if you'll go along with him on a proposition he wants to make you.

You won't fall down on me now, kid, will you? I know I ain't been much of a brother to you, but you've always been well to me, and this is the last time I'll ever have to ask you to do something for me. The last time either way, because if you don't come here with the guy that brings this to you, it's the cops for me, and the last long mile.

The letter wasn't signed, and it had been handled too much for

the prints of the writer to be left. Some of it was hard to read

because the ink was splotched by something wet that had sprinkled

it. But there was a date. Two days after that date, Mary had

appeared in Pig Lane.

THE mystery of Okdan Karolya's death was never solved.

Officially. But I have a notion how it came about.

The hunch came to me at, of all places, the circus. Some clowns gave it to me. The big arena was a hurly-burly of activity, but when these fellows came on I didn't watch anything else. Not because they were funny, or because they were such skilled acrobats, though they were both. I watched them fascinated.

And then they leaped on one another's shoulders, till they made a single column four men high!

The bright colorings of that human column seemed to change for me into the rusted black of threadbare capes. The glare of the circus dimmed to the shadowy murk of Hell's Corner just before dawn. I saw an open window high up in a blank brick wall and the top of the column leaning over into the gap. As I saw it in my mind, the top of the column was a man whose legs were so twisted he had to be held by his brother beneath him, but whose hands were so strong they could wring a man's neck.

"I see that act's going over big with you," Jack Sorley said to me. Jack has been a circus man so long there's a legend he taught P.T. Barnum the business. "Those boys are pretty good, but they got the stunt from the Three Grimsons. There was a troupe for you! They wowed all of America and half of Europe in their time, and they'd be doing it yet if they wasn't always going over the top for the underdog. They did that once too often, and it finished them."

"What happened?" I asked.

"They was doing a carnival turn down South during one winter layoff and they found out the guy running it was gypping his freaks. They threatened to turn him over to the law and gave him till after the night show to come across. They never played that show. A tiger somehow got loose in the tent while they were rehearsing in it, alone, and when the shooting was over they were mince-meat, just barely alive. Funny thing. They skipped out of the hospital the day before they were supposed to be released, and nobody's ever heard of them since."

Tom is blind, Dick is a deaf mute, and Harry's legs are so grotesquely twisted that he cannot walk. But Dick has eyes to see a wrong, and Tom has ears to hear the tale of it, and Harry has hands that can right it. I do not know whether they are brothers or not, but I know very well it is not from hell that they come, though they dwell in a cellar in Hell's Corner.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.