RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

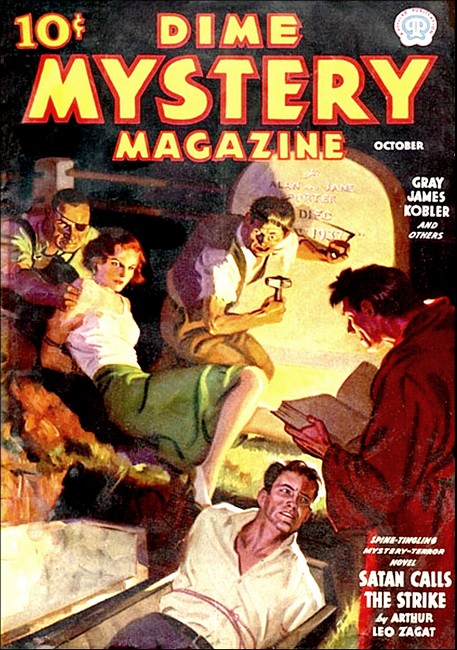

Dime Mystery Magazine, October 1937, with "Satan Calls the Strike"

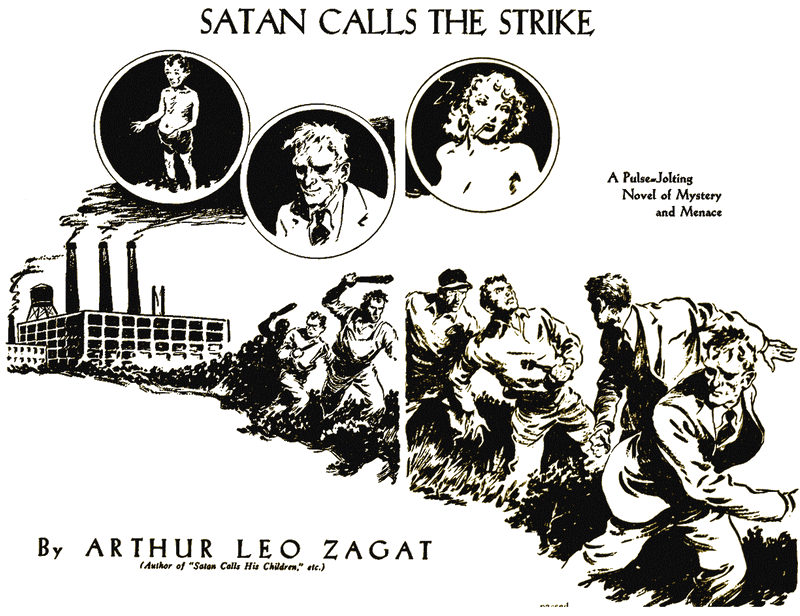

Death, Famine, and destructive Lust came, that hot summer, to the little town of Galeton—came in the forms of a sightless, cadaverous old man, a starved child of Satan, and an evilly voluptuous, blood-thirsting woman. No man could say whence came this hell-spawned trio; but their arrival turned a peaceful village into a town of terror and sudden, awful death.

NO one ever discovered how the first of the terrible three came to Galeton.

The Raunt Silk Mill, where seven-eighths of the town worked, had been shut down for a week-end overhaul, and the looms had been in such condition that the layoff had extended through that Monday. In consequence there were more than the usual number of loungers at the depot, but none of them saw the grey man alight from a passenger train or come up out of the freight yard by the only feasible passage. None of the women busy about the company houses that line Boston Turnpike at each end of Galeton recalled his entering the village.

Someone else might have passed the loungers or the women unobserved, but not Astaria. Not unless they were all suddenly struck blind as he went by them.

Sonia Szienkewicz, it is true, told afterwards of a whirpool of dust that drifted past her gate in the grey and brooding dusk. Such a miniature cyclone it was, she said, as a fitful wind sometimes sucks up, or as dances in the wake of a speeding truck. She was puzzled by it because not the slightest breeze relieved the sultry Indian Summer heat, and there was no truck. For this reason she watched the whirling dust jet as it whispered between the slattern fences of her mill-worker neighbors, breasting the little rise in the road there, till it vanished over the crest where the Turnpike becomes Galeton's Main Street.

Sonia swore that just at the instant the slope hid it, it took on human form. But Sonia Szienkewicz was known to be overly fond of the potato vodka she distilled in her cellar, and not even Pavel, her husband, believed her.

IT was Ann Wayne who first actually saw the stranger. She

froze to immobility in the doorway of the A & P, stifling a

small scream, and if the big bag she carried had not had a dozen

eggs on top she would have dropped it. As it was, she shrank back

against the red-painted door jamb and stared wide-pupiled at the

apparition that stalked past her parked roadster, walking down

the very middle of the street.

He was powdered with dust from head to foot, as though he had come a long way on the sun-baked Turnpike. The dust covered with grey his buttonless and oddly small shoes, his ill-fitting suit and his hat-less head that was somehow too large for his squat body, giving it an air of grotesque malproportion, emphasized by the unnatural length and thickness of his dangling arms.

But he was not altogether grey. His face was turned toward Ann as she came out of the store, almost as if he expected her; and it was his face that chilled her and twisted her throat with a soundless scream.

Over the chin and the mouth lay a crimson, five-fingered splotch, like the imprint of a gory hand. Where eyes should have been there were two black and empty pits!

Spine-prickling enough was that marred, blind countenance. What was infinitely worse was that it kept turning as its owner prowled down Main Street's gutter with his curiously soundless, gliding stride, so that those void sockets remained fixed on the shuddering girl as though to etch her picture firmly in the grey man's mind.

Ann Wayne was worth looking at. Her gossamer white frock made her a luminous small figure in the deepening, breathless dusk, as a white birch sapling is luminous in the twilit woods. She was slender and straight and graceful as a birch, but no tree could possess her tender curves of burgeoning womanhood, her wistful lips, the pert sweetness of her face that was now still and wan with icy fear.

Not until the stranger would have had to stop, or turn completely around to keep that blind look of his upon her, did he face forward again. He kept on toward Galeton's center, no hesitation in his progress, nothing in the way he moved to indicate that he had no eyes to see his way along that street where he never had been before.

Others spied him now. They watched him, their mouths agape, color draining from their cheeks to leave their countenances pallid masks of awe commingled with dread.

When the man came opposite the pillared front of the American House, he turned, abruptly, and went straight toward the hotel's entrance. He did not stumble at the curb, nor at the step-high edge of the low porch. The rocking chairs on the long verandah were rigid and soundless as his spatulate fingers closed unerringly on the door's handle, and he went through into the dim lobby.

Elijah Cantell, busy with some reckoning behind the desk counter, was aware of a sudden cessation of the drowsy murmur of the lobby sitters. He looked up—straight into that terrible grey face with its ruby mark of a muffling hand, a birthmark or burn scar, and its black eye-pits.

A sick revulsion ran through Cantell, but he was too much the veteran hotel man to let it altogether rob him of speech. "Yes?" he squeezed out. "What is it?"

If a voice can be called grey the stranger's voice was grey. "I wish lodging and board." It was an intonationless husk, one pitch above a whisper. "Your best accommodation." Each word was precisely enunciated, yet unshaded, unemphasized, as though the speaker uttered by mechanical rote, syllables alien to him.

To have this man living in the hotel and eating in its dining room would drive away all its guests. "Sorry," Cantell said. "We're full up." He lied, breaking the law that requires an innkeeper to accept anyone who can meet his price. "We have no empty room."

"I wish," the other repeated without any change of tone, "lodging and board."

"I tell you—"

Blackness swallowed Cantell's sight! Impenetrable, it thumbed his eyeballs as though it had weight and substance. Somewhere within the stygian night by which he was encompassed, monstrous things heaved, crawling out of some unnameable abyss to seize and drag him down into it....

"You are mistaken," the grey voice husked out of the sightlessness.

The things were rising out of the darkness toward Cantell! Almost he could smell their dank breath, almost feel their clammy, thumbless paws seizing him! "I—lied," he managed. "Lied...."

THE rayless dark faded to a throbbing blur out of which the

stranger's blank-socketed visage firmed, altogether

expressionless. Beyond its distorted periphery Elijah Cantell

could once more see the drowsy foyer of his hotel, a half-dozen

of his patrons seated in their familiar positions and gazing

furtively over the tops of their newspapers at participants of

the low-toned colloquy. There was in their faces a certain sick

fascination, but no alarm. The terrible darkness, Elijah

realized, had been in his own brain, not outside himself.

Somewhat to his surprise he found himself speaking. "Number five is my best room. It's right at the head of the stairs, and it has a private bath and a little private balcony." Automatically he rotated the register, automatically dipped a pen. "It is seven dollars a day, including meals."

He recalled that since the stranger was blind he could not write and put the pen back in the groove of its inkwell. Still half-dazed, he turned to take the key of room five from its hook on the rack behind him.

When Cantell came around again the man was just laying the pen down. On the register page, on the first blank line, a black scrawl glinted wetly!

Grey, nailless fingers plucked the key from Cantell's numbed hand. The stranger was gliding silently toward the balustraded stairs, the covert, pallid gaze of the lobby-sitters following him.

Elijah's mouth opened to call him back. He had no baggage, should pay in advance.... The hotelman made no sound. He could not make the demand. Dared not! If the blackness came again it might remain this time, and the things...

The stranger vanished on the landing above. There was a gust of relieved breath in the lobby and a shuffling of feet as with a single impulse, those who were sitting there rose. They came to the desk and crowded against it.

Cal Simmons peered at the register on which the grey man had written his name. "Astaris," he read. "Jest Astaris. No fust name or initial or nothin'."

"Where'd he come from?" someone asked. "Did he write down where he come from?"

"Yeah," Simmons grunted. "But it's kind of fuzzy, and I can't read it so good. Fust letter's H."

"Might be Hartford." another voice suggested. "Is it...?"

"No. It's too short for Hartford. It's...

"Let me see it." Mr. Meyer, sharp-faced, nattily dressed, shoved through. "I'll read it." Meyer was a travelling salesman and he was the only one who was acting quite naturally. "You get used to these hick grocers' hen-tracks and you can read anything." He got his hands on the corners of the register and bent over it, peering at it intently, studiously.

"I'll be damned!" he exclaimed. "The guy's quite a kidder." He laughed, but there was no honesty in it. "It's Hades he says he comes from. Greek for Hell."

Astaris. From Hell. Elijah Cantell stared over the heads of the crowd at the stairs Astaris had climbed, and dread lay like lead at the pit of his stomach.

ANN WAYNE swallowed, discovered that she could move again. She went across the sidewalk, leaned over the car door and deposited her bundle on the seat. The street lamps blinked on as she straightened.

"I knew there was some reason for this sudden illumination," a fresh, young voice said behind her. "'Tis the golden hair of my lady fair, shining like a good deed in a naughty world."

"Hush Tim!" Ann turned to the tall, long-limbed youth, a warm smile breaking through the nameless fear that still shadowed her face. "What kind of lawyer will people think you if they hear you chattering such nonsense?"

"A very wise kind." Freckles gathered in smiling crinkles, but something in the lines of his firm mouth hinted at repressed bitterness, and in his brown eyes there was no smile. "Maybe that's the answer. Maybe I ought to insert an ad in the Argus; 'Public Notice: As indisputable proof of his perspicacity, Timothy Woodruff, LL.B. announces that he is madly in love with—'"

"Silly!" The girl's tapering fingers on his arm stopped him. "Stop fooling, Tim, and tell me what's happened today."

"Nothing." Woodruff shoved a hand through his shock of russet hair. "The good people of Galeton still refuse to darken my door. In another ten years, perhaps, they will have forgotten that my father once was Shean Woodruff, foreman of the throwing room in the mill, and will come rushing to put their affairs in my hands, but I'll have starved to death by that time."

"Tim!" Ann exclaimed. "You're not telling the truth. I came into Uncle Henry's office a little while ago just as he slammed up the telephone receiver and he growled at me, 'If I had that red-headed rascal here I'd wring his neck'. You have got a case and it's against the mill."

"Old Raunt," Woodruff grinned reminiscently, "was at his sulphurous best. He flayed me alive, and he didn't use a single cussword. Look chicken, think you can slip away and meet me tonight?"

"Timothy L. Woodruff!" The girl stamped a petulant small foot. "You tell me at once what you called Uncle Henry about!"

"Swell," the youth exclaimed. "Ten o'clock then, in the summer house on your grounds." He wheeled and was gone in a single long stride into the murk of the grocery store.

"Sorry I am a little late," Henry Raunt's dry tones rustled in Ann's ears. He was coming around in front of the roadster, from his office across the street. "Did I keep you waiting long?"

HE was as sere and shrunken as his voice. Despite the sultry

warmth, his square-cut jacket was lightly buttoned and a high,

white cravat was folded around his corded yellow neck. Beneath

the brim of his black derby his face was the color and texture of

a walnut sheet, but there was a keenness in his black eyes that

belied his age.

"No, uncle," his niece responded demurely as she opened the roadster's door for him. "Not very long."

"Everything's ready at the mill and we're starting again in the morning. I waited to make sure that all the foremen were notified to have their shifts on hand. By the way," Raunt broke off. "Was that by any chance young Woodruff you were talking to as I came out?"

Ann's mouth twitched in an impudent little moue, behind his back. "Why uncle! You forbade me to talk to him, didn't you?"

"I'm glad you remember that." The girl went around to the other side of the little car and slid in under the steering wheel. As she heeled the starter button the old man laid his bony, transparent hand on hers. "I was afraid you thought me too harsh," he murmured. "I'm happy you understand I interfered only because I feel that the best is none too good for my little girl."

Ann hid her look of guilt with the business of gear-shifting, of tooling the car out into the roadway. She felt mean and ungrateful to the old bachelor who had been so good to her for the fifteen years since a railroad wreck had orphaned her. She might, even, have confessed her deception and asked her uncle's forgiveness for it, except for one thing.

Passing the American House something dragged her gaze up to the little wrought-iron balcony above its porch. A grey figure stood there, misty and wraith-like, ominously overlooking the town.

"SEEMS queer," Ed Fulton muttered to himself, "to be starting

the week on a Tuesday." He climbed carefully down the steep path

that snaked down the hill from his cottage. It was not yet full

light, and if he made a misstep he might slip and go tumbling

down into the road below, from which came the monotonous shuffle,

shuffle of thousands of feet on the way to the mill.

On mornings like this Ed wondered whether he was so smart building a place for himself up here in the woods, instead of living in the company barracks with the rest of the bachelors. In a month it would be black dark when he turned out, and he would have to use a flashlight. Maybe he was a fool, but he couldn't see staying among the Poles and the Hunyaks when he was boss of the jacquard looms, and the mill's most profitable product depending on the skill with which he set the almost human needles for their exacting work.

Now if he had a wife and a parcel of squalling brats, old Raunt would rent him one of the cottages on the Turnpike. The hell with that! He was better off like this. But he'd ought to have had better sense than to start out without his sheepskin jacket. The morning ground fog, swirling out from between the trees, was making his clothes damp so that they lay chilly against his skin.

Ed shivered a little. They were like ghosts, those thick wisps of vapor, on the path. That one just ahead, was exactly like a grey man, waiting for him....

"Stop, Edward Fulton!" It was a man, and he was speaking to Ed in a funny kind of voice, like a loud whisper. "Go no further!"

"What the blue blazes!" The little hairs at the back of Fulton's neck bristled. The man seemed built all wrong, but that wasn't so bad as the fact that he was blind. He had no eyes at all, and there was a nasty-looking red mark across the bottom of his face. "What do you mean stop? I got to get to work."

"There will be no work for you, Edward Fulton, ever again."

"The devil you say," the foreman grated, and started on down. No crazy guy was going to make him late, blind or not blind. "Get out of my way."

The grey wraith lifted a hand....

The workers in the road heard a shrill scream. Something came tumbling down off the hill. It hit the road-dirt with a fleshy thud, flopped queerly.

Ed Fulton lifted to his knees. To his feet. He was blubbering and he was knuckling his eyes. His face was grey as death itself.

And then he was screaming and laughing all at once. Laughing and screaming and crying, and the sound of it was enough to turn your blood to water. The sound of it and what he was screaming.

"I can't see. I'm blind. He's struck me blind. The grey devil has made me blind."

He started to run, and he bumped right into Manya Pavlovitch. She caught, and held him, "Wait, Ed," she said. "Wait. You're hurt. We'll take you to the hosp—"

Then Manya was screaming too. She was looking into Ed's eyes and she was screaming. Ed's eyes were red as fire and they had no pupils at all. They were just red balls glaring out of his face!

TIM WOODRUFF'S law office, over the A & P on Main Street,

was his living quarters as well. A screen hid a cot, and in the

bottom drawer of his second-hand desk were stowed a box of

crackers, a package of cheese and a paper container of milk.

At about eight that Tuesday morning Woodruff was pacing the floor of his office. He seemed to have been doing that all night, for the cot behind the screen showed no sign of having been occupied, and the young lawyer's blue eyes were bleared for want of sleep, his big-boned, blunt-jawed visage deep-lined with fatigue. But something other than mere weariness was limned on Tim's face. There was suffering there, and a certain bleak and terrible grimness that had no place on so young a countenance.

Sunlight came horizontally in through the window and struck into bold relief a white, typewritten sheet that lay flat and uncreased on the desk's green blotter, an addressed envelope beside it. Woodruff stopped prowling, stood looking down at the letter.

The youth shrugged. "Better get it off," he muttered, "so that it will be on record." He read the typing once more, carefully as if he were weighing each word.

Hamlin, Shane and Hamlin.

138 Fanuel Street, Boston, Mass.

Gentlemen:

I regret to report that Mr. Henry Raunt yesterday unconditionally refused the proposition for the purchase of the mill here which I made to him at your instance.

As Mr. Raunt is for the present in sole control of the property, this seems to end the matter. However, should there appear to be in the future any prospect of reopening negotiations with a reasonable chance of success, I shall seize it.

I will be glad to undertake any other matters with which you care to entrust me.

Very truly yours,

Timothy L. Woodruff.

"All of which means," Woodruff murmured, "to anyone reading it, that I've muffed my last chance. The commission on this deal would have given me a new lease on life, but it's no go. I'm through. Washed up."

He sat down, folded the sheet meticulously, slid it into the envelope. He sealed the envelope, took a stamp from the top drawer, affixed it. For a long moment his fingers drummed on the edge of the desk, as if, despite what he had said, the action were not quite final, as if there were some decision still to be made.

The drumming fingers dipped into the drawer again. They brought out two objects, put them on the desk, the letter between them.

The one on the left was a snapshot of Ann Wayne. Her small face laughed tantalizingly out of it, and one slim arm was outflung in a beckoning gesture strangely appealing. That which lay on the right was a yellowed newspaper clipping:

MILL WINS CASE

NO LIABILITY TO WOODRUFF

Judge Parker Gibbs today dismissed the case of Shean Woodruff against the Raunt Silk Mills. "While plaintiff has shown," he said, "that the machine which tore off his arm was negligently unprovided with safety devices, it was his duly as foreman to insist on such provision, and his failure to do so constitutes contributory negligence on his part, invalidating his claim."

After handing down the formal decision, Judge Gibbs made an effort to persuade the company to grant Woodruff a pension. He pointed out that by choosing to bring suit, the crippled foreman had waived his rights under the Workmen's Compensation Law, and hence was left altogether without support for himself and his motherless young son. "This man has served you faithfully for a great many years," the jurist ended his plea, "and it seems to me only human that you aid him now that he is destitute and helpless."

Stephen Wayne, vice-president of the company was obdurate. "Woodruff has been paid good wages for his work," he replied, "and we owe him nothing."

This statement was followed by a dramatic incident. Woodruff sat up on the stretcher on which he had been brought into court, and shouted, "You owe me plenty, and you'll pay it. Some day you and yours will pay what you owe." He turned to his six-year-old son, standing beside him. "I lay it upon you, Tim, to make them pay."

Timothy Woodruff read the clipping through, and then he looked

for a long time at the snapshot. Slowly his lids narrowed, till

he was peering at it through tight slits, his face an

expressionless mask.

"Washed up," he muttered. "That's what they think." He took the photo in his hands and he tore it across and across, with an odd, slow ferocity. Then he put the clipping away, picked up the sealed envelope and went down into Main Street to mail it.

THE mill and the long, drab barracks where the single men and women among its workers are domiciled, lie north of Galeton. On the other side of town, a line of small, boxlike cottages are given over to the families of the married men.

Here, in number twenty-six Vega Street, Maggie O'Boorn finished washing the mountain of breakfast dishes with a sigh. When there are a man and seven brats to feed, that matutinal task becomes a long and tedious chore. Pendulous-breasted, shapeless in a dingy all-over apron, Maggie mopped up the sink, hung up the rag, and shuffled to her kitchen's back door.

Festooned in the brilliant sun, variegated garments fluttered from a line stretched between two leaning poles. They were dry now, ready to be ironed. Maggie bent wearily, lifted a wicker hamper from the little porch and waddled down into the yard.

She went all the way to the back fence that kept a profusion of rank, high weeds in check. Long ago she had learned to work toward the house, so as to carry her heaviest load the shortest distance. She set the basket down, reached work-reddened hands up to the first of the clothespins....

She stiffened. From behind her, from the tangled brambles beyond the fence, had come a hollow moan, a moan so filled with suffering that in the instant she heard it Maggie O'Boorn's clumsy body turned cold as ice.

The low moan came again. She could not have heard it had she been a yard nearer the house. It seemed to have been going on forever.

Maggie came heavily around, took the one step needed to bring her to the fence, leaned over it. Her frightened gaze penetrated the interlaced, dark tangle.

"Mother Mary have pity," she whispered.

Not only the Mother of Mercy but Herod himself would have pitied the child that lay agonized in the netted brush.

It was a little weazened boy, his nakedness covered only by a few tattered, grimy rags, his dirt-encrusted skin so tightly drawn over the bones that every rib, every stringy muscle, stood out in sharp relief.

Maggie knew only that he was a child by his diminutive size. His face was flesh-less as an old man's, the lips twisted away from the rotted teeth in a skull's humorless and awful grin. It might almost have been a living skeleton that lay there, except that no skeleton ever had a belly like that; a blue-tinged famine-bloated bag against which hands like bird-claws pressed in a fruitless attempt to still the pangs that wrenched that low moan from between blue unconscious lips.

This starveling was the second of the three who came to Galeton that week. The first was met with horror, the second with pity. Maggie O'Boorn, reaching down over the pickets and taking the pathetic small form into her tender, mothering arms, could not know how soon pity was to turn to terror.

THE sun, bright through her eyelids, woke Ann Wayne. She

stretched in the soft luxury of her bed, eyes still closed, like

a fuzzy small kitten. She rolled over—and the pillow was

wet against her downy cheek.

Recalling that she had cried herself to sleep and why, recalling the resolution that had let her sleep at last, Ann thrust the sheet back and leaped from the bed. Darting across the silky rug, she was like a boy in the flashing white silk of her pajamas, her close-cropped golden curls a rumpled cap for her eager face. She reached a white-and-gold secretary between two windows where Venetian blinds were breaking the sun into slanting sheets of dancing dust motes, and almost before she had seated herself on the small chair she was writing:

Tim Dear—

I just won't let you go. It doesn't matter about half the mill belonging to me and your being poor, not the tiniest little bit. You made it seem so important last night and I was so terribly upset that I couldn't think, but I did think it all out after you left me and I know now that you are wrong.

Look, dear, I've thought of a wonderful way to make everything all right anyway.

Come to the garden house tonight at ten. When I hear your owl hoot I'll come out and tell you all about my plan. You're my lawyer, you know, even if you're no one else's. My lawyer and my man, forever and ever, Amen.

THE room door opened as Ann was slipping the folded note into

an envelope. "So ye're up!" a grey-haired woman, her form scrawny

in a gingham morning apron, exclaimed. "I didn't think, comin' in

after midnight like ye did, that...."

"Martha, darling," the girl interrupted, running to her, the sealed but unaddressed envelope in her hand. "Don't scold me this morning. Please don't scold me. I couldn't bear it."

"And when, since ye were a tad of six and I started tryin' to take the place of yer poor mother, God rest her soul, have ye been able to bear my scoldin' ye?" The tones were stern, but plain on the woman's time-seamed face was the deep, abiding love of a childless female who has one chick to mother. "The Lord knows you need a scoldin', traipsin' around half the night with that red-headed rapscallion, an' me pretendin' to yer uncle that ye're safe asleep in your room, the Lord forgive me for my sins. I tell ye, this is the last time...."

"Till the next, you old dear." Ann stood on tiptoe to kiss the wrinkled lips. "Martha," she continued, breathlessly. "Please give this to George quickly, before he leaves with uncle for town. Tell him to make sure and deliver it early, because...."

"Early!" Martha sniffed. "It's nigh eleven. Besides, George didn't drive Mr. Raunt to the town office. They went to the mill."

"The mill?" The girl took a step backward, the letter still tight in her hand. "Why, this isn't Thursday...."

"No. But there was a telephone call for yer uncle right after seven. There's trouble there."

"Trouble? What kind of trouble?"

"How should I know?"

"Well," Ann shrugged, "whatever it is, Uncle Henry will take care of it.... If he isn't going to town I can drive down and leave this for Tim myself. What do you think I ought to wear, Martha, my blue print or...?"

"Ye'll do no drivin' today, missie. Yer uncle left word that ye wasn't to go out. He was very particular about that. 'Tell my niece that she is to stay inside the house today.' Those were his very words."

The girl's eyes widened. "I'm to stay—Martha! He never said anything like that before. What does it mean?"

Martha spread her hands wide. "I'm sure I don't know."

"He said tell me, not ask me?"

"He said tell ye, and he meant it, make no mistake on it."

"Did he—do you think he knew I was out last night? Did he seem angry?"

"No. He was more scared like. More as if he was scared something might happen to ye if ye did go out."

"Scared! But—Martha, I've got to go. I've got to get in touch with Tim. Look. I'll get dressed and climb down the drain pipe outside my window here, and no one except you need know..."

"Ye'll do no such thing. Give me that letter. If it must get to that young reprobate, I'll take it to him."

THE buildings of the Raunt Silk Mill ramble over acres of

ground. Their age-darkened bricks are ivy-covered, so that the

small windows admit very little light and the long,

machinery-filled rooms are dim, and dusty and always damp.

Because of the dimness the weavers in the satin room must be doubly intent on the lustrous webs growing on their looms, watching the darting shuttles lest they be jammed for a split second and spoil a yard of the costly fabric, watching for knots in the woof, for breaks in the warp. It is no wonder then, that no one saw Astaris enter.

The first they knew of his presence was when his toneless half-whisper husked through the pound, pound of the pistons, through the clackety-clack of the spindles, not sounding over the familiar sounds but hissing through them, clear and distinct and startling.

"Stop," it said. "Stop work."

Anton Stane, foreman here, pulled the emergency switch that shut off the power; thinking, if he thought at all, that someone's sleeve had caught in a cog wheel. Then he looked and saw the grey man, halfway down the long, murky room, his columnar arm raised high over that great, blind head, the eye-pits cavernous.

A girl screamed in the sudden silence.

"What the hell!" Stane roared, plunging toward Astaris. "Get the hell out of here, before I break your damned...." His bellow broke off as he jolted into a dolly-wagon, instead of going around it, and then he was pawing frantically at his eyes, his voice high-pitched, shrill and wordless.

There was no silence, any longer, in the satin room. There was a pandemonium of terrified screams, a chaos of forms that ran everywhere, shrieking. Of forms that collided with one another, with the machinery; of stricken men and women who lurched blindly about fleeing the dark that had clamped down upon them, in a single instant; the impenetrable, tangible dark that had gouged sight from them.

Everyone of the two score men and women in that room had gone blind.

It took time to get the stricken workers, somehow, anyhow, to the infirmary where a bewildered doctor was looking down at Ed Fulton, scratching his head in puzzlement over what had blinded the old foreman. Fulton was lying on a cot, mercifully drugged to sleep.

It took time to quiet the people from the satin room, but the agonized cries were silenced at last. Henry Raunt was there by this time, and John Holdon, the mill superintendent, and between them they managed to get the tale out of Anton Stane.

"Where's this Astaris?" Raunt growled. "Where did he go?"

No one seemed to know. The guards at the gate in the high fence of steel mesh topped by barbed wire that surrounded the plant swore he had not passed them going in or out. A hasty but thorough search of the building did not reveal him. He seemed to have appeared out of thin air and vanished back into it.

After awhile some bright individual thought of 'phoning the American House. "Sure," Elijah Cantell said. "He's here. He just came in and went up to his room."

"Let's go get him," someone yelled, hearing that report. "Get him!" two hundred voices roared and the gate guards were swept aside by a yelling mob that poured out through the gap in the fence.

There was not one in that howling crowd who was not terrified of the blind, grey stranger. There was not one in that crowd who dared admit his terror to his neighbor. It was a mad rage born of fear that lashed them on, ravening, crazed by blood lust, along the Turnpike toward Galeton, toward Main Street and the American House.

MAGGIE O'BOORN took the pitiful waif into her house. She laid him on the big bed where her three boys slept and went into the kitchen to get a bottle of milk out of the icebox.

The child ought to be attended to by a doctor, she knew, but there was no telephone in the house. She would get a little nourishment into the starved thing, and after that would be time enough to send someone for Doc Watts.

It never occurred to Maggie to send the lad to a hospital. The poor are accustomed to take care of their own.

She warmed some milk and poured it into a cup. Then she went back into the bedroom, sat down on the edge of the bed and dribbled a little of the milk between the still blue lips.

Some of the white liquid dripped across the bony chin, but some went into the starveling's mouth, and it was terrible to see the tiny Adam's Apple work convulsively up and down in the small throat as the milk was swallowed. The first few-drops had a marked revivifying effect, and with the third spoonful the little hands grabbed Maggie's wrist.

The bent brown fingers were rough on her skin, and their long nails dug deep, like the claws of some rapacious bird. "Easy now," the woman said. "Easy. You'll get as much as is good for you and no more."

The boy's eyes were still closed but Maggie was talking for her own sake. "'Tis me own grandfather used to tell tales of the great hunger in the old country, when the potato crop failed, and how when the reliefers came to the villages it was only little by little they would feed the starving children." There was about her charge something frightening, something that made her feel cold all over though the heat of the day and of the range on which her irons were set made the house an oven.

There was something about the lad that was strange, uncouth, and it made her afraid. Something in the harsh dryness of his skin, in the way that the grey crust on it looked like the scales of a snake.

It was only the dirt, Maggie tried to tell herself, that coated him.

The spoon caught between his teeth and in pulling it out she jerked the waif's head around. And the horror of it!

He had no ears! This—thing—she had picked up out of the thorns had no ears at all on the sides of his head!

Maggie O'Boorn heaved to her feet. The room swam dizzily around her. She lurched out of it, out into the kitchen, crossing herself, mumbling a prayer.

The litany calmed her. She got hold of herself. "Now aren't you the scare-cat," she chided herself. "The poor lad has been abandoned by some unnatural mother because of his deformity, and he has been crawlin' around in the wood till he was famished to the very point of death. The Lord led him to you to save, and now you too would condemn him."

This was, of course, reasonable. Nevertheless Maggie did not turn back, but went on through the girls' bedroom and the parlor and out of the house. She had nothing in common with Becky Levy or Greta Andersen but she was going to call one of these neighbors of hers to come in with her. She dared not stay alone any longer with the—with whatever it was she had taken into her home.

THE sound of shrill voices met her, coming from the road, and

the padding of many bare feet. The children were coming from

school, coming home for noon lunch.

Her own seven were always a little later than the rest, but they would be here any minute. Maggie suddenly knew that on no account must they see that which lay in the boys' bed.

She forced herself around, hurried back to close the bedroom door. It opened into the room, so that she had to go all the way in to reach its knob. She glanced at the bed.

It was empty! The child, that a moment ago she had left barely conscious, surely too weak to move, was gone. He was nowhere in the room!

He was nowhere in the house! Maggie's frantic search was interrupted by a rush of small feet at the front door, by a clamor of small voices demanding lunch. "Hurry up, mom," Dan, the oldest, called. "I gotta get back for a couple innings ball practice before the bell rings. We got a game on this after—"

"Get your hands washed then, the whole kettle and boilin' of you, before you set down." There was nothing in the mother's voice to tell of the black fear-flood surging in her veins. "Be off with you now to the pump in the yard, and don't let me catch you wipin' the dirt off on the towels either."

She went through the scamper to the icebox. Lucky thing there was cold corned-beef and cabbage left over from last night. The youngsters would squawk but they'd have to eat it. "Kathleen! Get the bread out and slice it."

Maggie opened the icebox and took out the big platter she was after. She stopped stock-still, staring at it.

"Mom," Kathleen said from behind. "There's something wrong with the bread. Look, it's all green."

"Green," the mother muttered, but she did not turn. The meat on the platter in her hand was green too. It was covered over with a green slime and the stench of it was foul in her nostrils.

The bread was mildewed and the corned-beef was mouldy, and there was nothing in the icebox fit to eat. She'd looked over her supplies that morning, like a good housewife, and everything had been all right then.

"Meesis O'Boorn," Leah Levy's sniveling voice said from the doorway. "Momma vants I should esk if maybe you kin lend her a couple potatoes to cook for mein lunch. Our icebox is full mit ents, und dere ain't a t'eeng fit to eat."

THE noon sun rode high in a brassy sky. The elms bordering the

long, narrow park that marks Galeton as a typical New England

town seemed to shrivel in the breathless heat, and from the

baking roofs of the cars angle-parked along Main Street's curb a

quivering shimmer rose.

Tim Woodruff strolled with apparent purposelessness along the sidewalk in front of the American House. A woman came up from behind him, brushed against him in passing. Tim felt a tug at his jacket pocket as she went on.

Staring after her, he knew by the black bonnet perched atop grey hair, by the black satin waist and pleated skirt, that the woman was Martha Hutton, the Raunt's housekeeper. He felt in his pocket and his fingertips touched the crisp crackle of paper.

Woodruff glanced about for some place where he could take out the letter and read it unobserved. The hotel porch was deserted. One of its broad pillars would afford him the concealment he desired.

He went up to it, ripped the envelope, scanned it. Tiny muscles knotted his jaw and his eyes were agate-hard brown balls.... A sound came to him, turning his head. It was a muted roar as of a distant creek in spring spate, brawling between high banks, and it did not belong in the fall drowse of the hamlet.

Woodruff thrust Ann's note into his pocket, wheeled to peer north on Main Street, whence the curious tumult came. Just within sight, the wide thoroughfare boiled, its flanking buildings channeling a rushing human flood.

"They're coming to lynch him," a shrill voice gibbered in Woodruff's ear. "They're coming to lynch Astaris." Elijah Cantell pawed Tim's arm. "They can have him for all I care, but they'll wreck the hotel. They'll wreck—"

"That's your car there," Woodruff snapped. "Give me the key to it. Quick." The innkeeper fished in his vest, quivering lips writhing across his pale countenance, jerked out the bit of metal. The lawyer snatched it. "Lock your back door, shove something heavy against it and call the sheriff." Tim fairly threw Cantell toward his screened entrance portal. "I'll try to hold them here."

Woodruff vaulted the low rail, bounded across the pavement, grabbed open the door of a dull-colored sedan nosing the curb, jumped into it and jabbed Cantell's key into its ignition lock.

Heeling the starter button, he chanced a single glance over his shoulder. Through the rear window he saw the onrushing mob, only a block away now; saw maddened, bestial faces, a serried panoply of extempore weapons; wrenches, spanners, fence-rails, waving in gnarled and frantic hands. Then the sedan leaped the curb, smashed upon the tavern's porch, slewed to a standstill across its door.

The roar of the crowd deafened Woodruff as he slid out of the sedan. "Stop!" he yelled, his shout cutting through the tumult. "Stop right where you are."

PERHAPS it was his command that held them at the edge of the

porch. Perhaps it was their astonishment at perceiving the sedan

where no car ought to be, blocking them off. At any rate the

fore-runners of the mob halted; those behind piling up on them;

halted long enough for Woodruff to get to the gas tank at the

sedan's rear, to jerk open its hinged cap with one hand while he

slashed a cigarette lighter out of his pocket with the other and

held it over the aperture.

"Come a step further," he shouted, "one of you, and I blow you all to hell."

The mind of a mob operates curiously. They saw that indomitable figure, straddle-legged, grim-jawed, holding with steady hand the spark that would detonate ten gallons of gasoline. They heard his threat, and they did not think that if he carried it out he would he the first to die, did not speculate whether he would sacrifice himself to save a stranger. They quailed before his challenging stare, shoving back against the pressure of those behind, their rabid roar subsiding into muttering growls.

"What's it all about?" Woodruff demanded, following up his advantage. "What's this Astaris done?" If he could get them talking, arguing, they might not recall that there was a back way into the hotel. He was playing for time, for badly needed time.

"Done?" a big-thewed, granite-jawed fellow in overalls replied. "He's blinded Ed Fulton and Anton Stane and everybody in the satin room, that's what he's done." It was Dan Corbin, chief mechanic.

"Blinded.... Why that's nonsense. How could a man do anything like that?"

"Maybe he ain't a man. Maybe he's...."

Crack! Tim Woodruff went down like a poled ox. A stone, thrown by some urchin far back, had caught him square on the brow!

The mob surged up on the porch. The sedan was tossed aside as though it had no weight at all, and the sweating, shouting throng milled into the lobby. A chair went down with a crash, the desk counter toppled, splintered, toppled.

"He's upstairs," Elijah Cantell screamed. "Room five. He hasn't come down. Go get him but don't wreck—"

The armed, infuriated throng was abruptly quiet. The stairs rose from their cluster, unguarded, undefended. He whom they sought was trapped in his room at its head, but no one dared be the first to go up after him.

Woodruff's question, Dan Corbin's reply, had brought their terror back upon them. "Maybe he ain't a man," Corbin's words rang in their ears. "Maybe he's—"

What? What was this being who, without eyes, made his way about as though he were sighted? Who was seen now here, now there, and never in between—who, by a mere lift of his hand, could strike people blind?

In the gasping hush that lay suddenly upon them, one thought curdled the brain in every skull. "If I go up there, will he take my sight from me as he did from those others in the mill? Will he strike me blind?"

THEIR blood-thirst seeped away and a quivering, chill fear

took its place. Fear of the dark, first terrible fear that

assails mankind. Fear of the eternal dark, and the Things that

crawl in the dark. Fear....

"Cowards!" a woman's voice screeched. "Yellow bellies." Myra Stane was struggling through the crowd, and the crowd was parting for her. Her dress was half-torn from her scrawny shoulders, her hair straggled in wild disarray athwart her contorted face. Her eyes stared from their sockets, big-pupiled eyes in which there was no hate, no terror, but only madness. "You're going to let him go." She reached the stairs. "But I won't." She was running up, a screaming virago. "He robbed my Anton of his eyes and I'll kill him for it myself if none of you have the guts."

That shamed them into movement. The stairs were swamped by a rush of tossing, yelling men. The spell of fear was broken.

They poured into the hallway above. The woman, battering on the door of room five, felt the surge of hot bodies against her, crushing her against the wood, shoving her through the splintering panel. She went down, trampled by heedless feet, her screams unheard, and the room was filled with the crowd that was once more a ravening mob.

Only with the mob. Astaris was not there! He was nowhere in that room, though the bed, the dresser, every piece of furniture in it, were smashed to bits by the searchers.

Astaris had vanished from the room where it was certain he had been when the hotel was surrounded. Cantell swore that he could not have reached the back door without his being seen. It was impossible for him to have climbed down from the balcony to make good his escape. But he was gone.

Astaris was gone. The moments Woodruff had gained for him by his desperate stand had been sufficient for him to vanish, utterly.

The noon sun was a torrid ball, hanging high over Galeton. But in its streets a chill fear ran, the cold of a nameless terror.

LOCATING Timothy Woodruff had taken Martha Hutton longer than

she expected. Conscious that Henry Raunt would demand an

explanation of her absence from lunch, she decided on returning

by a little used shortcut to where the Raunt Mansion sat high on

its wooded hill overlooking town and mill and Company

Barracks.

She ducked into an alley between the drugstore and the bank, went across a cluttered vacant lot behind them and came out on a dirt road, the destination of which was the cemetery bordering Galeton on the west. Thus she missed the incursion of the mob from the mill.

Thus too, by pure chance, she witnessed the advent of the third of Galeton's weird visitors.

Martha had just reached the cemetery when she heard the rumble of an approaching vehicle behind her. The road was narrow and she crowded against the graveyard wall to let it pass.

She expected a hearse, or an undertaker's closed wagon, but what she saw was a flat-bedded small truck swaying toward her along the rutted trail. She glimpsed the driver, a weazened figure crouched over the wheel, his face hidden by enormous blue goggles, and then the cab was past her.

A long, narrow pine box was solitary on the stake-less platform, its shape marking it as one of the cases in which caskets are shipped.

The truck speeded up immediately after passing the housekeeper, so that it was already some yards beyond her before she resumed her journey. The left rear wheel hit a boulder past which the narrower front ones had gone safely, and in climbing it the bed of the vehicle was canted side-wise.

The case started sliding. The jolt as the wheel regained level served only to hasten the progress of the long, yellowish box. It went over the end corner of the truck, hit hard on the very rock that had caused its fall.

Martha Hutton cried out to the driver, but at that same instant the exhaust backfired, and her voice was drowned by the pistol-like report. When she called again the vehicle was already beyond hearing.

Martha reached the crate, saw that the impact had split it from end to end, and that a blackish loam was spilling out of the gap. It may have been the slight jar of her footstep that did it, but whatever the cause, the box slid off the boulder on which it was up-ended and fell apart.

The earth it had contained spread out, covering the splintered boards. On the bed that it made lay a woman's corpse!

The cadaver was so beautifully formed that it might have been the marble product of some master sculptor's chisel; thighs and flanks and nubile breasts melting into a single singing line; except that a cascade of night-black hair framed the sensitive, sleeping face and trailed across the abdomen's sensuous mound.

Martha Hutton's mouth went dry, and she felt icy, invisible fingers constricting her throat. But she did not run.

Something about the still form, some evanescent tinge of color underlying the white, transparent skin, perhaps some barely distinguishable movement, seemed to deny that it was veritably a corpse. Martha bent to it, herself scarcely breathing.

Were those long-lashed lids fluttering? The Raunt housekeeper bent closer still.

The white arms lashed out suddenly, were steel bands clamped around her neck, dragged her down! A stone cold face nuzzled into her corded neck and teeth, sharp, piercing, stabbed her jugular.

There was no one near to hear Martha Hutton's scream. No one near to come to her aid as her hands thumped cold flesh, frantically at first, then more and more feebly....

CONSTERNATION ran riot along Vega Street. Not a single larder in all the clustering small houses had been left untouched by the scourge. In some the food had mysteriously decayed, between breakfast and noon, in others it had been as mysteriously invaded by insects. Becky Levy's ants were as nothing to the brown swarm of roaches on Rosita Liscio's shelves or the white worms that slimed Arina Vassilyevna's cupboard.

"Ai," Becky wailed, out in the street where the distracted mothers were gathered. "It's the mokas the good Lord, blessed be his name, has sent on us, the plagues like he sent to the Ejeepchans."

"Run down to Rimpelmaier's, Selma," the blond, statuesque Greta Andersen directed her eldest, "an' ged some cheese an' bread for your lunch. Tell him ay pay Saturday."

The eminently practical Norsewoman's example was followed by a half dozen of her neighbors. There was a general exodus of youngsters to the corner grocery. "Yuh know," Fannie Hirst announced to the gathering at large. "I hoid somet'ing runnin' around in my kitchen 'bout nine o'clock, but when I looked there was nothing there. I t'ought maybe it was rats."

A chill crawled Maggie O'Boorn's spine. Was it the little starved boy Fannie had heard...?

"I seen someding chump out from my vindow." Gretchen Maier contributed, "Aber so fast it run into the voods, what it vass I could not see, eggsept dot it vass little und dirty-lookink—"

"What time was that?" Maggie squeezed out. "What time?"

"Aboudt a qvarter to ten."

It had been about half-past ten when she first heard that moan. Maggie had an appalling vision of the small, earless thing with its bloated belly scuttering all over town, darting into kitchens and darting out again, leaving destruction behind. There was an Old Country legend, she tried to recall, having to do with a leprechaun of famine.

"Mom! ... Ma!" The messengers who had been dispatched to Rimpelmaier's were running back, empty-handed. "Mother," Selma Andersen panted up. "There's a scum like mud over everything in the store. Mr. Rimpelmaier says he's got nothing to sell. I'm hungry, mother."

Hungry! All the children were hungry, and there was nothing to eat. Nothing at all to eat, on Vega Street.

CONSCIOUSNESS came back to Tim Woodruff with the pound of

running feet shaking the porch boards on which he lay, with

hoarse and rabid shouts resounding about him. "Find him! Scatter

and search the town! Find him before he gets away."

The feet rushed away, thudding on the concrete of the sidewalk. There was the burring of motor starters, the snarl of horns.

Woodruff's hand lifted to the throbbing ache in his temple, where the stone had struck him, and his eyes opened. He was lying against the hotel wall. The car with which he had blocked its entrance loomed above him, hiding him from the mob that was pouring out of the tavern. Lucky for him that it did, otherwise they surely would have turned on him, recalling that it was through him they had been robbed of their prey.

The rush of feet and the roar of cars died away, and the ache in Woodruff's skull lessened. He shoved hands against the boards, got his knees under him, waited an instant while the sick whirl in his head subsided, and started crawling out from within the sedan's shadow.

White sun-glare met him, dazzling him. "There he is," Elijah Cantell's high-pitched voice quavered above him. "If he hadn't held them up they would have caught Astaris."

The youth's groping hand found the rear bumper of the sedan and he dragged himself erect.

"He was right on the spot," someone else said, in dry tones that rustled like the wind in autumn leaves, "was he? Right here to stop the mob."

Woodruff's sight cleared and he saw that it was Henry Raunt who spoke, his old-fashioned garb immaculate as ever, speculation smouldering in his deep-set eyes. There was a third man with the mill owner and the hotel-keeper. The grey wings of a walrus mustache drooped on his leathery face, a badge was pinned to the lapel of his coat and his corded hands gripped a short-barreled riot-gun.

"Good work, lad," Sheriff Carter grunted. "We don't want no lynching in Galeton. Good work."

"Too good." Raunt's upper lip pulled away from his teeth in a sneer. "So good it might even be he had it all figured out before-hand. Did someone 'phone you the mob was coming. Woodruff, and did you hustle here to save your confederate from them?"

Little muscles knotted along the ridge of the youth's jaw, but otherwise there was no change of expression on his face. "What do you mean?" he asked tonelessly, weakly holding on to the sedan's spare tire. "What the hell are you driving at?"

In the street only a single auto was left, the mill owner's sleek touring car. Its motor was running softly and a uniformed chauffeur, seated behind its wheel was watching the group on the porch with avid interest.

"I mean that it's evident you brought Astaris here to terrorize my workers." Raunt's reply was low-toned but there was venom in it. Hate.

Carter stared at the mill man, astonishment written large on his weather-beaten face. "How do you figure that, Raunt?"

"He made me an outrageously small offer for the mill yesterday. When I refused it he told me that before long I'd be glad to sell at any price, if I had anything left to sell. If that didn't mean that he was planning to ruin the business I don't know what it did mean. This morning this outrage occurs, and when its perpetrator is about to be captured, who is it but this scoundrel that saves him?"

"But...."

"But nothing. Arrest that man, Sheriff Carter!"

The peace officer's look shifted to Woodruff. The red-headed youth was smiling now, mockingly and without humor.

"That suits me," he murmured. "Henry Raunt of the Raunt Silk Mills is good for any damages a jury will award me for false arrest. You've made a wild charge, Mr. Raunt, and you can't prove it."

"I'll prove it all right," the old man said grimly. "When you come to trial I'll have the proof that will send you to prison for a lifetime."

"Are you sure of that?" the sheriff asked, hesitant. "Are you sure you'll have proof enough to convict?"

"As sure as I'm standing here. Stop this fooling around. Carter. Arrest this man. Put handcuffs on him and lock him up."

The young attorney shrugged. "You are a witness, Cantell, that I'm being imprisoned on Raunt's complaint." He held out his hands, wrists together. "Remember that."

The sheriff fumbled a jangling pair of handcuffs out of his side-pocket, clamped his gun to his side with an elbow, and stepped forward to manacle the youth.

Woodruff's left hand lashed forward closed on the butt of the riot-gun, snatched it from under Carter's arm. In the same split-second his right drove into the sheriff's chest and sent him reeling against Raunt. The youth whirled, leaped the porch rail, hurtled across the sidewalk and vaulted over the low front door of his accuser's touring car.

He jabbed the stolen weapon into the chauffeur. "Get going, George," he snarled. "Before I blow your guts out."

The long-bodied auto surged away from the curb, shot south on Main Street. Woodruff crouched down in the space between seat and dashboard, concealing himself from any possible spectators, but the barrel of his weapon snouted very steadily at the driver's green filmed face.

"Your boss is too smart for his own good." There was steely threat in Woodruff's voice. "Don't you be smart and try any tricks or you'll get the same dose that's coming to him. Keep looking straight ahead and drive like hell!"

By the time Carter and Raunt regained their feet, the car was a distant cloud of dust. The tycoon's countenance was purple with fury as he twisted to the sheriff as if to strike him.

"You fool!" he flared. "He'll get away, and—"

"Not on your tintype he will," Carter grated, whirling toward the lobby entrance. "I'm sending out an alarm right now to the State Troopers. They'll have all the roads blocked, fifty miles around, in ten minutes. What's your license number?"

ANN WAYNE stared out of the window of her boudoir. The small

oval of her face puckered with worry, she overlooked the

mansion's gardened lawn, the high wall whose granite stones were

hidden beneath a thick blanket of century-old ivy, the long slope

of Gale Hill to the valley far below.

Dusk was settling over that far flung vista. Already it blurred the distant spread of the mill buildings, the elongated bulk of the barracks, the grid-ironed streets of Galeton. It seemed to the girl as though some tangible fear were drawing a grey pall over the familiar scene, some such brooding dread as lay heavy within her.

With utter futility she had tried to throw off that feeling of something wrong, of something menacing in the air. It had first come upon her when neither her uncle nor Martha Hutton had returned for lunch, had deepened when in response to her call to the mill, John Holdon had palpably evaded her inquiries, had assured her that nothing of importance had occurred there, that her uncle had gone down to his town office and was probably eating his lunch there.

She had dialed the town office and there had been no reply.

Had Martha betrayed her, giving Raunt her letter to Woodruff, telling him of their furtive meetings? Had there been an altercation between her uncle and her lover, an acrimonious flare-up of enmity between them?

Torn by anxiety, Ann had decided to disobey Raunt's injunction to remain within the house. She had been stopped at the door by old James, the butler. "May I remind you, miss," he had quavered, "that your uncle left strict instructions that you are to remain at home? I should advise you to do as he says."

She could, of course, have pushed James aside, run around to the garage and driven away in her roadster, but the habit of obedience was too deeply ingrained in her for that. Then, too, Uncle Henry must have some good reason for his unprecedented restriction. She had turned and climbed to her own suite, and had tried to read, hoping thus to shorten the time till Martha's return. But the print had run together on the page, and the words had had no meaning, and more and more heavily some fathomless dread had settled upon her.

She had now been staring out of this window for an hour. Signs of some unusual activity had come up to her from the valley; far-off shouts, cars rushing along the Turnpike, clumps of men appearing in the snatches of streets and pathways that were not hidden from her by foliage or buildings. All of it too far away for distinct vision, all of it somehow ominous.

If only she knew what it was all about!

Ann's dreary thoughts broke off. Someone was coming up the path from the gate in the wall, was coming toward the house. He was no one she had ever seen before. Medium height, he was so thick-set as to appear clumsy till one noticed how lithely he walked. His features were gross, heavy-jowled and swarthy. Though he was hatless he carried a bundle in one hand, white and shapeless as though a sheet had been knotted about some lumpy object.

ANN leaned out of the window to get a better view of him and

some sound she made attracted his attention. He looked up at her,

his beady, small eyes narrowing, his thick lips twitching, as if

with surprise... and something else.

"Yes sir," James' thin voice sounded, from the entrance below. "What is it, sir?"

The man's look drifted downward. "This Henry Raunt's place?" his harsh tones inquired.

"Yes, sir."

"Tell him I want to see him. Frank Hamlin, from Boston."

"I'm sorry sir, but Mr. Raunt is not at home."

"Not home, huh! When do you expect him?"

"I don't know sir. He did not say. Do you wish to leave a message?"

"A message. No. Just tell him that I'll be back." Oddly enough, the stranger's gaze slanted up again to Ann, so that it seemed he was speaking to her instead of to the butler. "I'll be back." he repeated, and there was that in his tone that sent a chill prickle scampering the girl's spine. "I'll be back."

Hamlin turned, and went down the path. Ann watched him till he went through the gate and was hidden by the wall. Her hand was pressed against the soft curve of her breast and against its palm she could feel the flutter of her heart.

Why wasn't Uncle home yet? What had happened to Martha? Why was there no word from her?

Who was Hamlin and why was his promise to return so palpably a threat? Did Henry Raunt know the man?

IT was not until dusk that the body of Martha Hutton was discovered. This is not as surprising as may at first appear. There was no such combing of the highways and byways of Galeton for the vanished Astaris as the enraged crowd from the Mill first intended. The search started vigorously enough, but from Vega Street word ran to them of the macabre happening there, of how every bit of food in the section had been destroyed and the children left hungry. Of the little, starved Thing that scuttered in and out of the cottages but had been seen only by Maggie O'Boorn.

The married men among that harrying mob recalled suddenly that they were fathers. They hastened homeward, their faces set and pallid, the cold fingers of fear tightening on their throats.

Their co-workers might lie blinded and moaning in the infirmary at the Mill, victims of Astaris' mysterious power, but it was their children who were hungry, their children and their wives who were threatened by some new, strange terror. The gray man might get away scot free for all they cared. Who would protect their families if not they?

The single men who were left to carry on the hunt were more terrified than they cared to admit by the prospect of meeting him they sought, the first heat of their rage cooling, and so they gathered in two or three roving groups instead of throwing a far-flung net over the town and the countryside. So it was not till the sun had set that one of these bands, following the cemetery road, came upon the smashed remnants of a pine-wood case, a heap of dirt, and a scrawny figure that lay upon them, stiff by then with rigor mortis.

It lay, face down and oddly contorted, on the black loam, and there was not a stitch of clothing to cover its nakedness but only a grey shadow. Hal Jenks, champion wrestler of the plant, bent to it. He put a huge paw on its shoulder and turned it over.... He leaped back from it, screaming like a hysterical woman.

Like a misplaced, toothless mouth, a wound yawned in Martha's neck, crisscrossed by the white threads of severed muscle and sinew, but it was not that which had ripped the shriek from the strong man's breast, not that which now held him and his companions rooted to the road by horror.

The sliced flesh was not red. It was pallid as so much veal drained of its blood. The flesh was bloodless, and the gaping orifices of artery and vein were empty. There was no blood in that obscene wound, no blood on the yellow, wrinkled skin, none on the earth where it lay. The corpse had been drained, sucked dry of its life-fluid. It was a juiceless, empty husk.

Lars Pierson, blond, nerveless son of Finland, was the first to find voice. "Gawd," he husked. "It's a vampire done this. I mind me old man telling about...."

"What's that?" Pete Harron gasped. "What's that?"

His arm was outflung, its quivering finger pointing over the low cemetery wall.

The others wheeled, saw a black, formless wraith moving among the graves, coming soundlessly toward them, blotting out one after another the pallid stones. They glimpsed it only, and then they broke and fled, winged by panic, across field and hill, to the safety of their Barracks....

Hal Jenks, slamming the great door and shooting its bolts, was startled by someone yelling behind him. A yell which was succeeded by a whimpering silence.

He jerked around, saw Dan Corbin standing above the cot on which they had left Kurt Weiss, too sick with a cold to work but not sick enough to go to the infirmary.

Kurt was there but he was no longer sick. He was dead. His throat was ripped open and no blood clotted it. There was no blood on his pillow and none on the sheet that was thrown back from his hairy chest.

THE moonlight crept blue and cold, across the floor of the

American House's half-demolished lobby.

The door of a sound-proofed telephone booth scraped open and Henry Raunt came out of it. "James says everything's quiet at the house," he said, sighing with relief. He turned to Cantell, sunk deep in a big club-chair, his head in his hands. "Turn on some light Elijah," he growled. "The few cents you'll save by keeping us in the dark won't pay for the damage here."

The innkeeper pushed himself out of the chair and shambled to a switch box in the wall behind the wrecked desk. A grimy, yellow luminosity spilled down from a high hung chandelier. Sheriff Carter turned from the window out of which he was peering into Galeton's deserted Main Street.

"I ought to be out there," he husked, "with a posse, hunting for Woodruff."

Raunt stared at him, cold contempt in his eyes. "You had him and you let him go. Now it's up to the State Troopers to capture him again. We've checked on their arrangements and he'll never be able to break through their cordon. Besides, where would you get anyone to make up your posse? There isn't a man in Galeton who isn't shut up behind locked doors and barred windows, afraid even to look outside for fear of being blinded or having his throat sliced."

"It's the children that are the worst," Cantell quavered. "The little hungry children."

"They're sending a train from Hartford," Carter said, "with food. I told you I had wired there an hour ago."

"How," Raunt queried softly, "are you going to get it distributed when it does come? Who's going to drive the trucks?"

The peace-officer threw his gnarled hands wide. "I don't know. I don't...."

The diminishing roar of a car outside, the squeal of brakes, cut him off. The three men in the lobby turned, slowly, fearfully to the door. There was the thump of a hesitant footfall outside it. The knob turned, but the lock held.

There was a revolver in the sheriff's hand as he leaned his head against the window glass. "It's—it's your chauffeur," he grunted. "It's George."

Henry Raunt beat him to the door. George stumbled in, his hat gone, dried blood matting his hair, streaking his temple and his cheek. Carter caught at him, helped him to a chair.

Raunt bolted the door and wheeled to his servant. "Well," he rasped. "Out with it. What happened?"

George lifted his head. "Right outside town," he said heavily, "he made me drive into the woods, in among the trees. I saw him jump up, all of a sudden and then he clouted me across the head. I went out like a light, come to about twenty minutes ago. This was nearer than the house so I drove back here. There wasn't nobody—on the road or on Main Street."

"No," his employer said, leaning over him. "Have you any idea of where he might have gone? Did you look around for tracks?"

"I looked," the man answered painfully, "but the dead leaves was too thick. I—I found an envelope on the floor of the car, but it was empty and it didn't have no writing on it."

"An envelope? Where is it?"

"In my—side pocket," George moved his hand to get it out, but Raunt's reached the pocket first and came away with a blank envelope that had been torn open, and another paper, folded.

"What's this?" he demanded, starting to open the latter.

The chauffeur stared at it glassily. "I—I don't know. I didn't know anything else was in there, but I was so dazed...."

"I'll be damned!" Raunt exclaimed. "He's come out in the open. Look at this, you two." He held the paper up for Carter and Cantell to read.

The words on it were in pencil, crudely printed. They said:

DOOM LIES IN WAIT FOR ALL WHO LABOR

FOR THE RAUNTS OR THEIR SPAWN.

THEY GO OR WE REMAIN.

THE THREE FROM HELL,

BLINDNESS—HUNGER—DEATH.

"I WAS screwy, was I, when I said Woodruff is to be blamed

for what's going on?" The tycoon's words thudded into a brittle

silence. "What do you think now?"

"I—I can't believe it," the innkeeper stuttered. "Tim's a fine boy. He wouldn't..."

"Do you remember what his father said in the courtroom, sixteen years ago? Do you remember his swearing the boy to revenge on Stephen Wayne and on me? It's Stephen's daughter Woodruff means by 'their spawn'. Ann, the daughter of my sister, Elvira Wayne, who was Elvira Raunt. Ann and I are the owners of the Mill now and he's taking this way to ruin us, to get revenge for his father's fancied wrong."

"But there isn't any real proof Tim stuffed that note in George's pocket. Maybe someone else...."

The desk telephone shrilled across Cantell's quavering defence of the young lawyer. The sheriff jabbed the receiver from its hook.

"Yes, this is Sheriff Carter.... Oh, Western Union." He sounded disappointed, but his next words were excited. "For Timothy Woodruff! Who's it from? What does it say?"

He listened a moment, the others watching him, tautly expectant. "I got it," he said at last. "Thank you." He dropped the receiver into its cradle and turned to his companions.

"That was a smart idea of yours, Raunt, to have me give orders for all wires for Woodruff to be 'phoned to me. One just came for him that ties him up plenty."

"If you ever lay hands on him," Raunt said dully. "What does the wire say?"

"'Deduct ten thousand our offer to Henry Raunt. Sure he will listen to reason.' And it's signed, 'Hamlin.'"

The corners of the old mill-owner's mouth twitched. "You believe me now, don't you?" He stood poised, expression draining from his tired old face. "You believe me." He was staring at the paper in his hand. At length he said. "Come on. George. Come on."

"Where are you going?" the sheriff demanded.

"Home. To draw up a petition to the court to permit me to sell Ann's interest in the Raunt Mills as well as my own and have her sign it."

"But—but there isn't any need for that. When we catch Woodruff—"

"If you catch him by morning and get him to surrender his confederates and they all confess to their scheme, it will be easy to tear up the petition. But if you don't do all that, all of it, I have no choice but to sell out. Do you think I'll ever get another soul to work in the mill unless they can be convinced beyond any doubt that the three who ravage Galeton are human and not fiends from the lowest pit of hell?"

He turned and shambled to the door, an aged and broken man. George stumbled to his feet and followed him.

"Maybe Tim Woodruff's taking advantage of what's happening," Elijah Cantell muttered, "but that Astaris ain't human, I'll bet my soul on that. No human could do what he's been doin'."

"What is he, then? What in God's name do you think he is?"

"I don't know. But I do know one thing. When he come in this noon his right arm bumped against the newel post of that staircase, and it wasn't the sound of flesh it made but the sound of something hard, like wood or metal. That right arm of his ain't natural."

"Well?"

"It was Shean Woodruff's right arm that was tore off in the mill. They made an artificial one for him but he died before he had a chance to wear it. He died, and they buried it with him in his grave."

ANN WAYNE watched the dusk fade into darkness, and the darkness lighten again with the cold blue light of a full moon.

The moonlight silvered the tips of the trees on the slope below, and it lay passionless and secretive on the road that came up the hill from the valley. Ann still waited for her uncle, for Martha Hutton, dread growing within her.

What had happened, down there in Galeton? What was happening to keep both her loved ones from her? And Tim, would he come at ten?

Abruptly the girl's hand tightened on the sill, and she was leaning forward, her lip caught up under her teeth. Was that a shadow she had glimpsed on the road, or was someone moving upon it?

The black shape came a little nearer and Ann could make out the familiar outlines of Martha's bonnet, of her ill-fitted black waist and her pleated skirt.

The icy shell that had been about the girl's heart broke. She could not wait till Martha got here. She must run and meet her.

She wheeled and ran down the stairs, out of the house. Her flying feet touched the gravel of the path so lightly that hardly a pebble was disturbed. She went through the arched gateway in the old wall, and down the road.

A curving bank still hid the woman she ran to meet, but Ann saw the moving shadow in the trail, fuzzy edged as moonlight shadows always are, and called out to her.

"Martha!" she cried, that fresh young voice of hers throbbing with relief. "Martha! What's kept you? Why have you been so...?" She choked off as she went around the curve and into the woman's arms.

It wasn't Martha! Even as those arms went around her, Ann saw that the woman who wore Martha's clothes was not her foster-mother. Bending back against the tightening band that held her, the girl stared into a white face framed by midnight hair, into inch-long lashes wide about eyes that were dilated and wholly mad, at colorless lips snarling away from needle-pointed teeth.

"Oh," Ann gasped, startled only, not yet frightened. "Pardon me. I thought you were my...."

She couldn't get the rest out because her breast was crushed against the strange woman's breast, and the breath was crushed from her lungs.

The woman laughed, a strange high laugh that had no merriment in it but only terror, and then her head dipped and her stone-cold face was nuzzling into Ann's neck.

Sound blasted in the girl's ears, a hoarse shout, and something pounded against her. She heard a scream as the clamping arms were torn from her, and then she was sprawling in the dirt with the bestial sounds of a furious combat snarling and snorting over her.

"Not her!" she heard a hoarse voice gasp. "Oh God, not Ann!"

IT was Tim's voice and, rolling over, Ann saw him disheveled,

the clothes half-torn from him, straining straddle-legged above

her. The woman's right wrist was clamped in his desperate grasp.

Her fingers clutched a gleaming stiletto, a stiletto curious in

that its blade was balanced on the other side of her fist by a

bulbous swelling from which dangled a great empty bag whose

fabric glinted oddly in the moonlight.

Woodruff's free fist exploded against the woman's jaw and she collapsed, a gutted meal-sack, in the road.

"Ann," Tim grunted, squatting to his haunches beside the girl. "Ann!" His face was a mask graven out of granite, deeply etched by some terrific internal stress. His palm, almost brutal, shoved her chin up and to one side, exposing the neck against which the woman's icy flesh had nuzzled.

Breath hissed from between Woodruff's tight lips. "What was it you had to tell me?" he demanded. "What did you want me for?"

This was not how Ann had dreamed it would be when she told him of her great plan. She had pictured his arms around her and hers around him while she whispered it. He seemed a stranger now, staring down at her with burning eyes, a stranger somehow fearful. But she answered him.

"I won't take my half of the mill." she said, "since it makes so much difference to you. When I'm twenty next February and the estate is to be settled I'll refuse my inheritance. You'll arrange it. Then I'll be as poor as you and...."

"Ann!" Some inexplicable spasm twisted Tim's countenance. "You love me as much as that. And I...."

"Look out," the girl shrieked. "Behind you! Tim! Behind you!"

The blind grey man had stepped out of the black woods, had spied them and halted, the moon-shadows blackening his vacant eye-sockets till they were stygian hell-pits.

His right arm shot up over his head as if in command. "She's for me ..." he whispered.... Tim Woodruff exploded from his crouch in a low diving tackle across the road. His outflung arms clamped Astaris' knees, his shoulders twisted and the blind man pounded down.

Astaris' great head crunched against a tree bole—and split open! Its two halves spun away, two hollow spheres of papier maché, and Ann Wayne was staring at another face, the gross, heavy-jowled features of Hamlin, the man who had visited the Raunt mansion in the dusk and had promised to return.

"It was a mask," she gasped as Tim rose to his feet above the unconscious man from whom the revelation had stripped horror. "Look, far back in the eye-sockets there were lenses of dark glass and he could see through those."

"Yes," Woodruff said, his voice oddly unresonant. "It was a mask and he could see ..." Motor roar, unnoticed till now, drowned his words, surging around the banked curve. He twisted to it, and Uncle Henry's touring car nosed around the bend, skidding to a halt.

"Got you," Henry Raunt grated. He was thrusting the short barrel of a gun under the windshield and its muzzle snouted pointblank at Woodruff. "Got you red-handed! Nice of you to leave this riot gun on the seat here. Put up your hands or I'll blast you and take pleasure in doing it!"

TIM'S arms went slowly above his head. "All right," he

muttered. "Don't shoot." He seemed slumped in defeat, the