Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

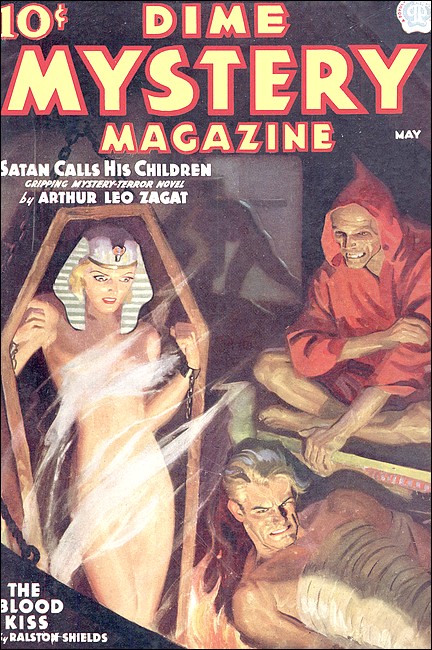

Dime Mystery Magazine, May 1937, with "Satan Calls His Children"

It was nothing to Jennie Gant that she chose a path which led straight into horror beyond human imagining, or that she was surrendering her lovely, youthful body to savage lusts that could breed only in evil darkness. For her little brother was in the hands of Satan's henchmen—and she was going to his rescue....

THE air lay thick and steamy against Jennie Gant's thin cheeks, against the round firmness of her bare arms. It sapped the crispness from the blue smock that hugged her slim, young form, but it curled her black, short-bobbed hair more tightly about her pert features.

There was a bite in the air, the sharp sting of strong soap, and of the cleaning powders Izzy Horowitz scooped into the first wash water far back in the dimness of the big laundry, where the big drums swished and rumbled. It cut Jennie's nostrils, and throat, and made her cough.

She would keep on coughing after she went home, and Dickie, her little brother, would look at her with big dark eyes too worried for his seven years, till she kissed the worry out of his eyes, telling him it didn't mean anything, telling him that all the girls who worked in the Super-clean Laundry coughed like that.

Bob Coffey wasn't so sure the constant little hack didn't mean anything. Bob was just studying about occupational diseases in medical school, and last Saturday he had talked anxiously about the weakening effect of "persistent irritation of the bronchial tract."

Jennie had used the soft argument of her velvet lips to silence Bob. Thinking now of Bob and Dickie, while her deft hands stripped damp stockings over the hot metal leg standing straight up in front of her, and stripped them off again dry and gleaming with the soft sheen of fine silk, the sureness of their love was a warm ache in Jennie's breast. She wondered if the Garden Avenue deb whose sleek legs this gossamer web would cover tonight was half as rich in affection and tenderness.

The corners of her wistful mouth twitched bitterly. The deb didn't have to slave from seven in the morning to five-thirty at night so that her small brother might have clothing to warm him and food on which to grow strong and straight. The deb's sweetheart didn't have to spend his night patrolling a warehouse down by the river to keep himself alive till this long years of study should be over.

Jennie's right hand picked up a wet stocking from a basket to the right of the silvery gleaming leg, and slid it onto the leg. Her left hand slid it off and tossed it into another basket at the left while her right hand picked up a wet stocking from the basket to the right, slid it onto the leg....

The Boss had picked Jennie to work at this machine in the window because she was good to look at, and good at her work.

It was nice sitting here to do her work. It was nice watching the different patterns the sun made, sliding through between the ties of the Morris Street "El."

There were always lots of people out there, queer-looking, queerly dressed. There were bearded old Jews in long black coats and round, shiny hats. There were Sicilian laborers, collarless, swarthy, their white teeth flashing under drooping, tar-black mutachios. There were shambling, tired-looking women, shawls hooded over faces brown and wrinkled as the coconuts on the pushcart near the corner, sharp eyes roving the carts for bargains. And there were the kids.

MARIA LEVENITCH came along the sidewalk, pushing a

dilapidated baby-carriage. The threadbare brown blanket in

the carriage was tucked in around Baby Andros so all you

could see of him was his chubby little face, just waking

up. Maria brought him around every afternoon when she did

her marketing, and would stop here so he could watch Jennie

work while he crowed at her and flapped his sweater-covered

arms at her.

Maria was stooped over the carriage as if she couldn't straighten from bending over the washtubs all day. Her bony hands were red and cracked. Under her rusty-black widow's dress her uncorseted figure was scrawny and awkward, and she walked as if she were so tired she would drop if the carriage wasn't holding her up.

Her round head was covered with a shawl and she was dish-faced like all the Sylvanian women. But Maria wasn't ugly. Not when she looked down at her baby. Her pale eyes were shining. Her weary mouth was touched with a quiet sort of smile, all love and pride and tenderness. The smile made her almost beautiful.

She stopped the carriage right in front of the window. Little Andros tried to get up, but the blanket wouldn't let him. His mother went around to the side of the carriage and pulled it loose.

The baby's arms darted eagerly out of confinement, reaching to be picked up. Some makeshift toy was clutched in one little hand, and Jennie's throat went dry as she saw stark, utter terror flare in Maria's face.

For a minute the woman didn't move at all but stared at Andros, her eyes like holes somebody's thumb had dug out of her dough-white, quivering mask of a face. Then her suddenly blue lips opened, rounding, and though Jennie could not hear her, she knew the word they shaped.

"No!" Only that. But it was a soundless cry of agonized protest.

It seemed to free Maria from the paralysis that had seized her, for all at once she snatched the toy from the baby's hand, dashed it to the sidewalk with a strange fierceness, and then had Andros in her arms.

She held him to her, so tightly that his little body flattened the pillow of her breasts, so tightly that it seemed she was trying to crush him back into the safety of her body from which so recently he had come. She showered kisses on his face, on his tiny lips that were puckering, uncertain whether to cry or laugh.

Jennie's hands kept moving in the mechanical routine of their work, but she didn't know it. She knew only that she was staring at a mother's unexplainable anguish, at a mother who was—unmistakably—kissing her babe farewell!

Was it the thing Andros had held that had terrorized Maria so? Jennie looked for it, saw an unconscious foot kick it toward the corner curb. It was just a bundle of small black sticks the thickness of wooden matches and twice as long, tied together by a narrow ribbon of gray fur. The girl's eyes came questioningly back to Maria.

In the instant they had been away from her, a change had come over Maria. She seemed more controlled now, and there was a hardness about her face as if she had come to some decision. She had put the baby back into the carriage and as her work-worn hands covered him with the blanket they lingered with an odd reluctance.

She straightened, and looked around her with peculiar furtiveness. Then she was wheeling the carriage toward the corner, a peculiar slinking stealth about the way she moved. Like that, Jennie thought, a rabbit must appear, sneaking toward the safety of its burrow with a fox in sight that had not yet spied it.

The carriage reached the curb, stopped there as a towering truck hurtled from the direction of the river to cut off Maria's strangely furtive flight. Maria's bent arms straightened....

And deliberately she shoved carriage and baby over the curb, straight in front of the thundering truck!

HORN blare, a shout, hammered against the glass

through which Jennie saw this. Wood splintered under huge,

skidding tires. A wire carriage wheel bounded crazily

across the cobbles, hit an "El" pillar and spun. The truck

lurched to a stop—too late.

A woman screamed.

Morris Street pelted toward the corner, toward the rocking truck, toward the jumble of splintered wood under its wheels that was being swiftly died scarlet by an infant's blood. Morris Street shouted, in a dozen foreign languages; screamed, and streamed toward the corner where a baby's life had been blotted out.

Maria was on her knees. Morris Street thought she had slipped on a banana peel, on some bit of slick debris dropped from a pushcart, and that in falling she had thrown the baby carriage forward to its destruction.

But Jennie Gant knew different! Her fingers all thumbs on the door latch, getting it open and throwing herself out into the screaming, shouting street, she knew she had seen murder done. Jostled and bumped by people running too fast to look where they were going, she knew she had witnessed the planned, deliberate murder of a babe by its mother whose love for him had been a white flame glorifying the ugliness of a pushed-in, flat face.

She reached Maria, still on her knees with nobody looking at her because they were too interested in what was going on in the gutter. Jennie bent to her.

"Why?" The girl's voice was hoarse because her throat was so tight. "Why did you do it when you loved him so much?"

Maria's eyes lifted to her, and they were like the eyes of someone who had died. "No," she husked. "I slip."

"You lie!" Jennie saw the bundle of black sticks on the ground right by Maria's knee. She picked it up and shoved it almost into the woman's face. "You killed because of this, because of something it told you." She knew, all of a sudden, that this was so, just as surely as she knew her own name. "What did it tell you?"

Maria's lips were like gray worms writhing in her gray face. They whispered: "I no have the money to buy heem from Satan, so I geeve heem back to God."

JENNIE GANT couldn't quite believe she had heard the words. They meant nothing, or they meant something so horrible she didn't dare understand them.

The terror was back in Maria's eyes that looked past Jennie. Her face was livid and her mouth was twisted open as if she were shrieking, but she made no sound at all. Jennie caught the terror, so that spinning around to see what it was that Maria looked at, she threw her arm up to defend herself from....

From what? There was nothing, no one, on the sidewalk to be afraid of. There was only more people; men, women, kids; running to join the crowd at the corner, panting because they had run so far and jabbering questions at each other as they ran. They bumped each other, but they didn't bump one figure that paced calmly along the sidewalk. Even in their excitement they twisted and veered so as not to come too near him.

He was tall and thin, and his black silk cassock emphasized the somehow awesome dignity of his slow walk. A big black cross dangled from a chain of black beads that came out from under his square-cut, long black beard. His features were sharp and hawk-like, his black eyes burning with a brooding dark fire under the black-tasseled, diamond-shaped black hat he wore.

He was Papa Anton, the priest of the Byzantine Church on Hogbund Lane where the Sylvanians worshipped in the mysterious manner of their mysterious, homeland where Europe and Asia come together at the top of the map.

Where the Sylvanians worshipped! Maria was a Sylvanian, and....

Something tugged at Jennie's hand! No, not at her hand—at the fur-tied bundle of sticks she held, plucking them from her startled fingers. She whirled, saw a flurry in the crowd as someone plunged through it, already hidden from her by the jostling, excited backs.

A wordless cry came from her throat.

She dived after the one who had stolen the little fagot that was the key to what Maria had done.

Jennie shoved frantically at those stubborn backs, whimpering, "Let me through. Let me through." She thrust her slim, trembling frame in among them. Shoddy cloth rasped her cheeks, her arms. Unwashed bodies stank in her nostrils. Someone swore at her. She pounded against a back that wouldn't move out of her way because it was squeezed so tightly by other backs on both sides of it, and the crowd behind shoved against her, so that she couldn't move.

Jennie sobbed, knowing that the one she was after had got away. Or maybe he was one of those who was squeezed against her in the crowd. How could she know? He would have the sticks hidden, and it was only by them she could tell him from the others.

Through rows of craning necks she saw the high side of the truck rising and swaying and moving backwards, and she heard a gasp from those in front who could see what the big wheels were being lifted from....

All of a sudden there was a loud crack behind her, like a backfire. But it couldn't be that because it came from the sidewalk.

EVERYBODY turned to that sharp sound, Jennie

too.

Maria was folding over forwards on the pivot of her knees, and there was a great hole in her forehead over her left eye, black-edged and scarlet-centered. Her right hand was falling faster than the rest of her, as if the weight of the gun it held was carrying it down. The belt holster of a motorcycle cop who was bending over Maria was empty. His hands were still reaching out to help her up, and surprise was just coming into his big-boned, weather-bronzed face.

Someone shoved in front of Jennie, so she couldn't see any more, but the whole story of what had happened had been there, in that second of stopped motion that was like a still in the lobby of the Palace. The cop had bent to help Maria get up and she had pulled the gun out of his holster and killed herself.

It wasn't because she had murdered Andros that she had done that. She wouldn't have bothered to make it look like an accident if she had meant then to kill herself too. She would have gone under the truck's wheels with the carriage. She had sent a bullet crashing into her brain to escape some punishment she hadn't known was coming to her, till the moment she had looked past Jennie and terror had flared into her face.

Was it for saying what she had to Jennie that she was to be punished? Jennie was certain now that the sticks were a clue to what had threatened the baby. That was why they had been snatched out of her hand.

Some movement in the crowd, some accident in the way it surged to get to this new excitement, to lap up this new sensation with its thrill-thirsty eyes, shoved Jennie out of it; so that she would have fallen over Papa Anton, kneeling beside Maria's sprawled body, if the cop hadn't caught her arm and held her.

The strong feel of his fingers on her elbow, his blue uniform and his silver badge in front of her eyes, calmed Jennie a little, cleared her head. She must tell him what had really happened, that Maria had killed her baby purposely, and why.

"Get back," he growled. "Get back and give the father a chance." And he shoved her against the shoving people behind her.

"Wait," Jennie said, "wait. I want to tell you..."

"Let the sin of this poor lost soul be buried with her in her grave," Papa Anton's deep voice boomed out, drowning her gasped exclamation. He was praying for the dead, but why was it in English he prayed? Why did his eyes—almost on a level with her own, he was so tall—catch hold of hers so fiercely and burn into Jennie's brain? "She is now before her Judge, and it is not for you who yourselves will so soon be judged to condemn or absolve her." Then he was touching Maria's breast with the black cross he wore on a black chain, and the booming syllables that came from his lips were in no language Jennie had ever before heard.

"What were you goin' to say?" the cop asked.

"Nothing," Jennie whispered. "I'm so upset I didn't know what I was saying." Inside of her she was telling herself she had changed her mind because all of a sudden she had realized that no one would believe what she had wanted to say, but she knew she was lying. "Let me go. I've got to get back to work. I've lost enough time already."

She had. She must get back to work. Even though she was sick, and all mixed up, and—afraid—she had to get back to her machine in the window.

THE crowd melted after the morgue wagon came and took away Maria and what was left of baby Andros. The truck drove off. A street cleaner pitched the jumble of smashed wood that had been a baby carriage into his wheeled garbage can, and then used a hose to wash the cobbles and the sidewalk clean.

In a little while Morris Street was the same as always. The peddlers were yelling again. The shawled women were pinching oranges with their gnarled, wise fingers and the kids were playing in the gutter.

The sun didn't make any more patterns on the pushcarts. It was getting late and the little bit of sky Jennie could see was clouding over.

Jennie couldn't stop thinking about what had happened. When she closed her eyes she could see the terror in Maria's face, and she could feel the black sticks in her hand so distinctly that she could count them. There had been ten of them, and they had been tied together with a ribbon of grey fur.

There must have been some reason for the way they had been snatched from her.

Jennie had no idea what they meant, and the cops would have laughed at her if she had told them her hunch that they had something to do with Maria's killing Andros. But—Jennie's heart started beating faster as she worked it out—but if more things happened to others around here and more sticks were found, then they might be a clue to whoever was behind what was happening.

That was the answer! Maria's baby was not the only one threatened with something so awful she had thought death was better! The terror had not ended, it had only begun.

If that were so, Jennie should have told the cop about the sticks in spite of what Papa Anton had said. Now it was too late.

But something ought to be done about it. Jennie's head was in a whirl. She didn't know what to do.

"Why don't you stop with them stockin's?" Izzy Horowitz said. "Don't yuh know it's quittin' time?"

IT began to drizzle as Jennie hurried along Morris

Street toward Cherry Avenue and home. She was worried about

Dick, wondering if he'd have sense enough to close the

windows. He'd been a little feverish that morning. His nose

had been running, and she'd told him to stay in that flat.

She had asked Sonia Gorgio, across the hall, to go in once

in a while and see how he was, but Sonia had five kids of

her own. She might have forgotten and Dickie might be very

sick by now.

Cherry Avenue, when Jennie reached and turned into it, was like some place she had never seen before. There was hardly anyone in the street, and the few who were hurried as if anxious to be between four walls.

Even though it was raining, there should have been children running about, the children of the Sylvanians who had made these tenement-lined blocks their own, except for two or three families like the Gants who lived here before the heavy-bodied, round-headed foreigners came. But there were none at all.

The lights of the street lamps seemed to be closed in under their shades by the dismal dark, so that the shadows between them were blacker than they had ever been.

Something seemed to be creeping after Jennie in the shadows behind her. She told herself there was nothing there, but she was afraid to turn and make sure.

She crossed the street and saw, in the middle of the next block, light streaming out from Otto Erlauber's stationery and candy store that was on the ground floor of the house where Jennie lived. Her apartment was on the top floor.

"That's it!", Jennie said aloud. "Mr. Erlauber will know what I ought to do about the sticks. I'll stop and ask him, right now."

She should have thought of the old German before. He knew everything except how to make money. And he was her friend. Every night she went down to the back room behind his store, and he'd teach her the things she ought to know if she was to be a good wife for Bob when he became a doctor. He had rigged up an electric bell from upstairs so Dickie could call her:

There he was, leaning on the imitation marble counter across the open front of the store, looking out under his dripping awning into the rain.

"Ach!", he exclaimed as Jennie came past the newspaper stand and up to the counter. "Chennie! It is nice that you stop to say good evening to a lonely old man." He peered at her through his thick spectacles. "But is it that you do nod feel so goot? In your cheeks the roses are faded, and your smile—where iss it?" He could speak perfect English, but liked to amuse Jennie with those Germanisms, till they had become a habit.

The light made his white hair silky. It beat down on his great head, bringing out with every fine line of the thousands that netted his face and puckered the corners of his twinkling kindly eyes.

"Mr. Erlauber," Jennie gasped. "You know Maria Leventich from the second floor front? She stopped at my window this afternoon and when she started to lift up baby Andros, he was holding...."

She stopped, with a scary feeling that there was someone behind her, that there were eyes on her. Her head jerked around.

Papa Anton was behind her, looking over the top of a newspaper he held in front of him as if he were reading. His black, fierce eyes burned into Jennie's brain.

In the next second they were hidden by the newspaper, but Jennie Gant knew that they were there. She dared not say anything more to Mr. Erlauber while the tall black priest was listening.

JENNIE never knew what the words were that rasped

from her dry throat, or whether the sound made words at

all. She turned and almost ran out from under the awning

and into the fine, chill drizzle again.

She didn't go up the stoop next to the candy store and into the house on whose top floor Dickie was waiting for her, because even then she remembered that she needed milk and bread and a can of beans for supper, and that she would never be able to climb those five long flights again. She ran down the block to Zbick's grocery on the far corner and as she ran she could feel the tall, black priest's eyes following her.

There were four of the stocky, blue-eyed Sylvanian women in the grocery when Jennie came into it. Mr. Zbick was waiting on one of them, but the others had been whispering in the middle of the store, their shawled heads close together.

The minute Jennie opened the door they went silent, drawing away from each other, their round flat faces suddenly blank. It was as if a veil had dropped over their faces, over their pale blue eyes. But the veil couldn't hide the fear that lay deep in those eyes.

The woman at the counter, it was Rivcha Chesmy, had a red-headed little girl in her arms, hugged her close to her body.

Jennie had to wait a long time till it was her turn to be waited on. It seemed hours before Mr. Zbick had wrapped her loaf of bread and her can of beans and was dippering a pint of milk into the can she had left with him in the morning.

Mr. Zbick marked how much Jennie owed in the notebook she fished out of her bag, adding the small sum to the other small sums that she would pay on Saturday. Then she was out in the street again.

Papa Anton was no longer beside the newspaper stand, but Mr. Erlauber was selling three cigarettes to a man whose wet overcoat was hunched up about his collarless neck and Jennie was in a hurry now to get to Dickie so she didn't stop.

She went up the stoop into the tenement hallway. Usually the hall was noisy with the shrill voices of women, the guttural ones of men, the laughter of children, coming through thin walls of the flats and their thin doors from which the paint peeled in the little brown flakes. Tonight there was hardly any sound at all, only a low rumble of voices, and from the second floor the cry of a sick baby.

Somewhere ahead Jennie heard the patter of little feet, climbing the stairs in front of her.

There was something queer about the sound of those feet, and it set little prickles chasing each other up and down Jennie's backbone. It was a little scrape, scrape, scrape, like claws would make on the worn wood of the steps.

The very hall, so strangely hushed, was afraid.

That was silly, Jennie told herself. She was nervous because she was so tired, because of what had happened in front of the laundry.

But when the stairs ended at the top floor there was no one there, and Jennie had not heard a door squeak open and closed on this last landing.

Then it must have been a rat in the walls. The Lord knew there were enough of them in the house. Of course it was a rat....

JENNIE'S key rattled in the keyhole of her door,

her hand shook so. "Hello, Dickie dear, how do you

feel?"

"A'right."

His little head, curly as Jennie's own, but blonde as hers was dark, was bent in absorption over something with which his little hands were fussing. "Looka the Injun wigwam I just made."

"Look at the mess you've made," Jennie snapped, her tone sharper than she meant because of her exasperation at the nonchalant way he accepted her coming home. "Newspaper cut up all over the floor. And you've been using my manicure scissors, you bad boy." Putting down her bag and the package and the milk can on the rectangular, unpainted table in the middle of the room, she went toward the youngster. "Has your nose been running? Have you coughed any?"

"No. Ain't this a swell tepee?" He lifted it to her, blue eyes dancing in his pinched, pale face; the hole where a front tooth was missing making his grin impish.

"Isn't," Jennie corrected mechanically. Then her heart bumped against her ribs. An iron band squeezed her forehead, and her eyes were so wide they hurt, staring at the thing Dickie held up to her.

It was a small cone of newspaper neatly pinned around a framework of sticks whose ends stuck out through the top, where they were tied by a piece of string. The miniature tepee was about twice the height of a wooden match. The stick-ends were the thickness of matches, and they were black!

The sticks out of which Dickie had built his wigwam were exactly like the sticks in the fur-tied bundle that had been the last toy with which baby Andros ever played!

Jennie took the little tent from Dickie. "How—where did you get these sticks?" It was hard to talk. But then, it was harder to think, with her brain going around in a whirl. "Who gave them to you?"

"Nobody gave them to me. I foun' 'em on the floor, just a little while ago, over near the window. They was tied with a little piece of fur." The boy rustled the papers, pushing them aside to look for it.

Jennie had swept up before going to work, and there certainly had been nothing like that on the floor then. The fire-escape platform was outside of that window, but the window was closed and locked, and Dickie could not reach the lock.

"Who was here today? Who came in here?"

"Nobody." Dick was on his hands and knees now, still looking. "Only Mis' Gorgio when she come in to gimmie lunch, an' Uncle Bob."

The boy chuckled. "Was he surprised when I opened the door and yelled 'hello doctor' afore he got halfway up the last stairs."

"How did you know it was him?" Jennie asked, glad to have something to talk about while she tried to pull herself together.

"Gee, that was easy. You know how he walks, gimpy like. You can know it's him comin' a mile off."

Bob dragged his left leg a trifle because his knee was stiff from something that had happened to it, playing football on Morris Street when he was a kid.

"You're sure no one was here except Mrs. Gorgio and Bob?" Impossible that either had brought the sticks into the flat. But how then...?

"Sure I'm sure.... Here's the fur, Jennie." Dick jumped to his feet and pushed it into Jennie's cold fingers.

The hair was grey. It was stiff and coarse, coarser than the hair of any cat's, any dog's, Jennie had ever known. The inside was bluish-white, like Maria's lips had been.

There was a word printed in indelible pencil on the inside of the fur. One word. "Silence."

"What's the matter, Jennie?" Dickie's voice was scared all of a sudden. "Why are your eyes so big and black? Why is your mouth so funny? What's the matter?"

"Nothing's the matter, hon. Nothing at all. I was—I was just trying to stop a sneeze."

There was nothing to get scared about. These sticks didn't mean the same thing the other bundle had meant. There were only five, not ten, and the word on the inside of the fur told the message they brought.

If Jennie kept mum about what she had seen that afternoon Dickie would be all right. If she didn't....

What would have happened to Dickie if Papa Anton had heard her finish talking to Mr. Erlauber? In God's name what would she have found here?

She didn't know and she didn't want to know. Wild horses wouldn't drag another word about Maria out of her.... Jennie was surprised to find that she had both her arms around Dickie, hugging him close to her. That she was kissing him fiercely, greedily—the way Maria had kissed her baby just before she had—had thrust its perambulator in the way of a hurtling truck....

THE little body in Jennie Gant's arms squirmed, pulling away from her. "I'm hungry," Dickie said. "When are we gonna eat?"

Jennie made supper and served it somehow, managed to eat a little though the stuff tasted like hay and stuck in her throat, going down. She managed somehow to smile at Dickie, to get him undressed and washed, to hear him say his prayers and tuck him into his little bed in the living room.

Her feet stumbled as she started inside to her bedroom.

"Where are you goin', Jennie?" Dickie asked sleepily from the bed. "Ain't you goin' down to Mr. Erlauber's?"

"No. I'm tired. I'm too tired."

The boy sat up. "But you must," he cried. "'Member, you made me promise to make you, no matter how tired you are, like you make me go to school no matter how much I don't want to."

"Tonight's different, hon. I'm not going tonight."

"Then the next time I don't want to go to school that will be different too, an' I won't go."

She couldn't answer that. She couldn't tell Dickie why she didn't want to leave him alone tonight, and she couldn't think of a good lie. She never lied to him. And why shouldn't she go. He would be all right, as long as she obeyed the warning of the sticks.

"All right," Jennie gave in. "I'll go. But be sure to push the bell button right next to you in the wall if you want me for anything. You will push it right away, won't you?"

"Of course I will, Jennie. G'night, big sister."

"Good night, little brother."

Jennie made sure all the windows in the flat were locked before she turned off the light and went out into the hall. She made sure the door was locked.

She looked down the stairs, down into the dim silent well of the stairs. It was so far down to Mr. Erlauber's store. She would be so terribly far away from Dickie if he rang the bell. And suppose he didn't get a chance to ring it?

But the walls were thin and every sound in her flat could be heard in the Gorgios'. She would ask them to keep an ear out for Dickie. Jennie knocked on the streaked door next to her own.

Feet shuffled inside. "Who there?"

The man's voice sounded scared through the wood. Awfully scared. "It's Jennie, Mr. Gorgio. Jennie Gant. I want to ask you something."

"Jus' a meenit." Jennie heard the sound of something heavy being shoved away from the door, like some heavy piece of furniture had been holding it closed. The lock clicked, and the door opened.

It didn't open very far, only just enough so that she could see Pavel Gorgio's bristled chin, and a slice of wool undershirt, and it stayed that way, as if Giorgio was ready to slam it shut any second.

"W'at you want?" his thick voice rumbled.

"I'm going downstairs for a while and I wanted to ask you to listen for any sound from my flat. Sonia has a key so you can go right in."

"You go down alla time. Why you no ask that before? Why you only ask that tonight?"

"I—I'm nervous tonight. I—I'm afraid something might happen to Dickie."

"Afraid." The door moved a little, so that the light from inside fell on the man's hand. A big hand it was, stubby-nailed, black grime of the earth he dug worked into its cracks and seams so that they could never be scrubbed out.

"What do you...?" A yowl—the yelping howl of some enraged beast—cut across Jennie's question.

A woman's scream shrill with pain and terror, joined it. They exploded into hideous snarls, yelps.

Frightened children screamed from inside the flat.

PAVEL GORGIO was no longer blocking the entrance.

Jennie batted the door open with her shoulder, ran after

his burly, running form into the kitchen of the flat,

through it into a bed-room beyond.

She saw a huddle of screaming kids on a huge bed, saw a woman, Sonia Gorgio, at an open window beyond them. Sonia's mouth was open, but the scream was no longer coming from it. Scarlet streaks gashed her face, her wrinkled brown breast from which the kimono hung in shreds. The rags of a torn sleeve fluttered from her arm and on its flabby round there were the red marks of small teeth that had sunk deep.

"Sonia!" Pavel grunted plunging to her. "W'at...?"

"Carlo. He ees taken. I could not hold heem. Look." She twisted that bitten arm of hers thrusting out through the window, pointing through it.

Jenny reached them as the man vented a guttural exclamation; oath and heart-wrung groan in one sound. She leaned out of the window with them, her body crushed between theirs.

The iron bars of a fire-escape platform, the same upon which Jenny's own window opened, slatted across her vision. But through them, on a far down slant of the wet-gleaming iron ladder she saw a small dark form descending. Small—it was Carlo the four-year-old youngest of the Gorgio brood, in his grey wool nightie.

He wasn't climbing down the ladder! He was underneath it, slinging himself down by arms and oddly prehensile legs on the ladder's underside, and he was mewling and spitting and snarling like nothing that had ever been human.

Below him, blacker in the blackness, a shapeless thing moved to the foot of the ladder. Carlo dropped into that formless shadow....

Shadow—and Carlo—melted together into black. Jennie realized the others were no longer on each side of her.

"Eet ees your fault," Pavel Gorgio's hoarse bellow pulled her back into the room. "You were too steengy to pay. Your fault...." His arm was upraised, the sledge-hammer fist at its end knotted to strike his wife.

Something in Sonia's pose, rigid, poignantly tragic, stayed that blow.

"Steengy? Yes. For these othairs. Steengy weet' the money that mus' buy food for their bellies." She pointed to the four whimpering, trembling little girls on the big bed. "An' I had faith in the cross."

Jennie saw it, the strange black cross of the Sylvanians' strange sect, shattered on the floor. And atop the fragments, as if for all its light weight it had smashed the cross, she saw a fagot of ten black sticks bound together with a scrap of grey fur!

"WHAT is it, Sonia? What is this night? What is

happening?"

"Jennie!" The woman, bleeding, distraught, looked at her as if for the first time. "Thees is not your affair. Get out."

"But...."

"Get out!" Sonia pushed at Jennie with furious strength, pushed her past the heavy table that had been against the door, pushed her out into the hall. The door slammed.

The walls whirled dizzily around Jennie. She swayed, clutched at the banister for support. She didn't know what to do.

"They are bewildered aliens in this strange land. They are prey to the exploiters of their new country and to the superstitions of their old. Who can live among them and not pity them, and not desire to help them?"

Mr. Erlauber had said that once, when Jennie had asked him why he spent so much of his time talking to the dumb, stupid Sylvanians, so much time advising them. "Even against their will, their wish, it is our duty to help them whenever we can." If anyone could help the Gorgios, Mr. Erlauber could.

Jennie slipped, flinging herself around the turn of a landing. Her hand, pawing at the wall to save her from falling, ripped away a length of bellwire that was tacked to it. She gasped, her heart jumping in her throat, stopped and flung herself around to it. It was the wire from the push button beside Dickie's bed bell in the room behind Mr. Erlauber's store. If she had broken it...! She hadn't. She had only pulled out one of the staples that held it.

Jennie started running down again, but what had happened reminded her of Dickie, and she was again afraid for him in spite of what Pavel Gorgio had said. She would tell Mr. Erlauber about what was happening as quick as she could, and run right back upstairs.

Her feet hit the bottom landing and she darted around under the slant of the stairs to where one door led to the cellar stairs and another, at right angles to it, to Mr. Erlauber's back-room.

He didn't open. Maybe he was out in the store, waiting on someone. Jennie didn't care. She knocked again, rattled the doorknob. Still her old friend didn't come to open it.

Had something happened to him too? Jennie leaned against the door, putting her ear close to it, trying to listen through it. She heard only the throb throb, of the blood in her own ear....

Suddenly fingers clutched her arm, digging in, twisting her around. A scream started in her chest....

"Ach, its Chennie!" Mr. Erlauber exclaimed. "I thought...." Behind him, a grotesque silhouette against the pale rectangle of the cellar door, open now, was Joe, the hunchbacked half-wit janitor.

Joe had a bucket of coal on his shoulder. Jennie understood that Mr. Erlauber had gone down to the cellar for coal for the stove that kept his store warm and that Joe was carrying it up for him.

"You are trembling, Chennie," the old German was saying as he peered into her face through his thick lenses. "Something the matter is, hah? The little Dick...."

"No. Dickie is all right. It's Carlo Gorgio...." Jennie checked herself as Joe's apelike head jerked toward her, its thick lips drooling, its eyes red-balled and bleary. "No. Nothing's the matter. I just came down for my lesson and I was running because I was late."

Mr. Erlauber's face showed that he understood she didn't want Joe to hear what she had to say. "So let us go in and begin." He stuck his key into the door and unlocked it.

THEY all went into the room where Mr. Erlauber

lived, and Jennie stood looking around her while Joe

shambled past and out through a curtained doorway into the

store.

It was a little room, but it was neat as a pin. Two of its walls were covered with shelves full of books, all the way up to the ceiling, and more books were piled against a third wall, handy to a cot whose blankets were folded at its foot in a square whose edges looked as though they had been sliced with a knife.

In the middle of the room was a desk with a green-shaded lamp on it, and papers covered with writing in little angular letters as clean-cut as if they had been engraved. Another table against the fourth wall held a two-burner gas-plate. Above the table were more shelves with neat rows of shining pots and dishes, and boxes and cans of food. Next to it was a sink and a small icebox.

Joe came back. He lumbered past her, his crooked body almost as wide as it was high, his arms hanging down almost to his knees, his hands black with coal and curled like a gorilla's.

Mr. Erlauber closed the hall door behind Joe. Then he turned to Jennie.

"Well? What is it dot troubles my Chennie?"

She told him, the words tumbling out from between her lips, about Maria and about the sticks out of which Dickie had made a wigwam; and about the Gorgios. He listened, his face getting graver, his blue eyes darker behind the glasses that made them twice as big as they should be. He nodded when Jennie described the sticks, and when she was getting to the end he plodded over and lifted a big book down from one of the shelves and took it over to the desk.

"It can't be true," Jennie cried, as she finished, "what Maria said! Satan isn't real, is he? He isn't here in Morris Street?"

The book fell open to a page about in the middle. "Never, my dear Chennie, say dot anything cannod be true. One thing I have learned in my long years of study and wandering, dot the more science man learns, the less he knows about the eternal verities. Science muddies the waters of truth...."

"You mean...?"

"I mean dot belief, call it religion or superstition, makes true whatever is believed. When five hundred million people belief dot bread and wine may be transformed by faith into the flesh and blood of their God, then it is true as dot water can by an electric current be transformed into a gas. When five hundred people belief dot on one certain night of the year Satan is free to roam even this mechanistic city and change their children into hounds of hell, den all your science cannod deny it."

"But...."

"Dese old eyes have beheld things incredible, my Chennie. Once in the Transvaal, I recollect, an eland pale like a corpse long dead...." He cut off, stopped by a tinkle from the store that told someone was opening the door. He sighed, pushed out through the curtain.

JENNIE heard the door slam closed. She heard

footfalls come across the floor; rap, scuff, rap, scuff.

Bob's footfalls, unmistakable! She pushed the curtain aside

to call to him.

Her lover was picking up a box of cough drops from the counter, shoving a nickel across to Mr. Erlauber. She saw his long, narrow student's face, his high forehead and dark, tired eyes. But she did not call his name.... There was someone else in the store. A tall man, black-gowned, black-bearded, black-hatted!

Had Papa Anton come in with Bob or had he been out there all the time, overhearing what Jennie had said to Mr. Erlauber?

Jennie must have made some sound, because Bob turned and saw her. "Jen!" he exclaimed. "Sweetheart!" and then his smile of gladness faded. "What's the matter, hon? You look sick." He was limping toward her, his face anxious. "You look—terrified."

The black priest's eyes were on Jennie, orbs of black fire in an ominous face. "I'm just tired, Bob." She could lie to him once, but if he asked her another question she could not lie again, and Papa Anton would hear her. "But you're due at the warehouse. You mustn't stop here talking. If you're late again you'll be fired."

"Gosh," Bob said, looking at the clock on the wall. "That's right. But...."

"Hurry, Bob."

"Night, sweetheart." He was turning. He was going to the door. Jennie let the curtain fall between her and Papa Anton's terrible look. Her legs were weak, so that she had to put her hands on the desk to hold herself up. One of them touched the book. She looked at it, trying to tell herself that there was no real reason for her to be afraid of Papa Anton.

The book was open to a picture, yellowed with age. The scene was a clearing in a forest. The devil was coming out of a big hole in the ground. In front of him was a woman holding a baby in one arm while her other hand held out a necklace of pearls to the devil.

Behind the woman there was a child that was like a dog from the waist down, and another that had the head of a dog on a little boy's naked body. A man was running away through the trees, and the thing that ran after him was a dog, except that its forelegs were human arms and hands, and the shaggy hind legs had human feet.

A bundle of black sticks.... A bell over Jennie's head started ringing, its shrill sound piercing her ears, stabbing her breast. Dickie's bell! The way it rang was as if Dickie was screaming to her, screaming for help.

Jennie flew out of the door into the hall, threw herself at the stairs. The bell stopped ringing, all of a sudden.

That was more terrible than if it had kept on.

SOME time must have gone by between when Jennie heard the bell and started up the stairs, and when she reached the top floor—but she didn't remember any of it. It seemed that one second she was in Mr. Erlauber's room and the next she was holding on to the knob of her flat door with one hand while with the other she was trying to get her key into the keyhole.

"Dickie!" she yelled. "Dick."

There wasn't any answer. There wasn't any sound at all from the other side of the door. "Dickie!"

The key rattled in the lock against a background of awful silence.

The key caught, turned over. "Dick." The blackness inside took Jennie's scream and smothered it. She thumbed the switch beside the door jamb and the room jumped into being.

Dickie wasn't in his bed. He wasn't anywhere in the room. Jennie ran into the bathroom, whimpering. "Dickie. Dickie." She ran in and out of the kitchen, in and out of her own room, knowing she wouldn't find him, hoping against hope that she would.

She did not. The little boy was nowhere in the flat.

But the door had been locked and he didn't have a key to lock it from outside.

Maybe he had slid down under the bedcovers. Jennie ran back into the front room, grabbed the blankets and pulled them loose.

The blankets were still warm, the sheets were dented where his little body had lain. In the depression a bundle of black sticks lay, tied together by a scrap of grey fur. A bundle of ten black sticks. Not a warning. A sign of what had happened to her little brother. A sign that Jennie was being punished for having talked out of turn after the five sticks had warned her not to.

Jennie stared at the black fagot, and it was as if she were having a nightmare. The inside of her was filled with a terrible fear. She couldn't move and she couldn't make a sound.

Not that it would do her any good to scream. She had screamed before, with the door open, and no one had come.

They had sense enough to be afraid. They had sense enough to keep mum about that which it was forbidden to talk. They would not destroy their loved ones with their tongues, as Jennie had done.

What was happening to Dick? For what awful purpose had he been taken?

The weight of the blankets pulled them out of Jennie's numbed hand, pulled them off the bed. They uncovered another tiny bundle of sticks.

There were only five in this bundle, and the ribbon of grey fur that tied them together also tied a piece of paper to them. There were words printed on the paper, in indelible pencil. Jennie read the words.

You cannot help him. Attempt it and the earth will engulf you too in enternal agony. Do nothing, say nothing or the doom of Satan's night overtakes you.

THE words traced themselves in letters of fire

on Jennie's soul, and then they were fading, were gone!

There was only the blank paper, tied to the sticks, their

meaning....

Cold lashed Jennie's cheek, cold rain whipped against her cheek by a cold wind. It twisted her to the window. The open window! She had left it locked.

Jennie started for the window. A pair of nail scissors, the ones with which Dick had cut the newspaper, were on the table. She snatched them up, and then she was leaning out of the window, her aching eyes straining through the slatted grid of the fire-escape platform, probing the rain-filled darkness.

She was just in time to glimpse, far down, a small dark form descending the last iron rungs of the last ladder. Dickie! Who else could it be? A shapeless shadow received him and flowed away into the glistening darkness of the backyard.

Jennie shoved the scissors into the pocket of her skirt. Her knees thumped the sill, shoving her through the window, out on the fire-escape.

A panic gibbered at her, terror froze her motionless on her knees. Once before she had received a warning and ignored it. If she ignored this one....

Dickie was down there, the little brother she loved, the tot she had promised her dying mother to cherish and protect! Jennie came upright on the iron slats of the fire-escape. Then her feet were on the slippery wet rungs of the ladder, and she was going down, so fast that it seemed as though the far-down yard were pulling her down to it, down to her doom.

Water on the broken concrete splashed icily on her ankles. Jennie peered about her in the gloom, garbage smell in her nostrils, fear tightening her throat. The rain sifted down on her, soaked into her clothes, pasted them cold and wet against her skin. But it was not from the cold that she shuddered.

The stinking dark filled the yard—Darker still, a shadow lay against the black loom of the broken fence. Dickie must be in that shadow, a part of it. It was moving, going away from her! Taking Dickie.... Jennie sobbed, threw herself wide at the shadow to fight it, to tear Dickie away from it before it got away.

The ground vanished under her feet. She dropped into abysmal blackness!

A scream tore Jennie's throat, was smashed back into it as she smashed down on hardness that crashed the black into her skull.

SOMETHING pricked Jennie's thigh. A sharp point

stung her arm. She struck at it, waking from the oblivion

that momentarily had claimed her. Something squealed in the

dark. Tiny feet scuttered away, claws scraping on stone.

Jennie's eyes opened to darkness. If she had thought the night black before, then what could she call this velvet ebony that lay against her eyes like something palpable?

Jennie's stomach knotted. Her head ached where she had hit it, and inside it there was a dizzy whirl. She shoved her hands against slimy stone on which she lay, pushing herself up to a sitting posture.

All around her she heard the scuttering, scraping sounds of uncountable small things. She pulled in a breath, pulled in with it a smell of rottenness, a stench of things foul when alive and now dead for a long, long time.

A green spark lit up in the blackness, another, close to it. Two more, and two more, appeared, and then there were hundreds of the twin green lights all about Jennie in the dark. They were eyes! They were eyes watching her, hating her!

Fur rubbed against stone. Something squealed. Jennie knew that squeal. She had heard it before, in the wall of the tenement.

Jennie knew now what it was that had nipped her to consciousness. She knew now whose eyes it was that watched her out of the dark, waiting for her to stop moving, waiting to leap on her and tear her flesh with sharp teeth. Rats! Hundreds, thousands of rats.

Jennie jumped up, her skin crawling with the imagined feel of the rats. The rats' eyes blinked out. The scutter of their running feet was like the patter of a storm on the roof. But they did not run far. The green sparks of their eyes blinked into being again, not far away. They watched her. They knew she couldn't get away from them. They knew they would have her if they waited long enough. And they were waiting.

"Lemme go. I...."

It was Dick's voice, far away and muffled at once as though a hand had been clapped across his mouth, but unmistakably the voice of her little brother. You couldn't fool Jennie about that.

JENNIE forgot the rats. She was listening for

the voice again, for Dickie's voice. She didn't hear it

again, but she did hear the sound of someone moving, very

far away. The thud of heavy feet, of feet that scuffed on

stone, far away and getting farther.

Jennie started running. Right at the rats she ran, forgetting her fear of them, forgetting everything except that she had heard her little brother's voice, that he was somewhere there ahead of her, and that she must get to him.

Slipping once, she was thrown against the wall, and it was round and greasy with rotten slime. She was running a little downhill, and all of a sudden her feet were splashing in water; in greasy, oily water that splashed on her ankles and stuck to them, running off from them only slowly, so thick it was with rot.

Once more Jennie slipped. The thick, stinking water splashed into her face.... Her feet couldn't find the stone floor! She was in a bottomless pool of the soupy water!

Jennie went crazy altogether when she realized that. She couldn't swim and she had been always afraid of drowning, and she was going to drown in this awful stuff. She fought it, wildly, frantically, hitting it with her threshing arms, her flailing legs, and the more she fought it the more it splashed into her mouth and her nose, cutting off her breath, choking her.

She had sense enough not to breathe in the poisonous stuff, making her throat tight against it, against her screams. But she couldn't stand it any longer. Knives were cutting her lungs, blackness was throbbing in her skull. She was going to die!

Dickie....

Hands grabbed Jennie under the arm-pits, dragging at her. Her head came free of the water. Breath gusted into her face, breath that was hot and foul. Her face was shoved against the body of her rescuer and filthy hair matting that body scratched her face, got into her mouth. This was no human being that was lifting her out of the pool where she had almost drowned. It was an animal....

Was it a huge rat, huge as a man, that was saving her from drowning? Vaguely Jennie knew that that couldn't be so, and then she didn't know anything any more.

JENNIE GANT was cold. Her whole body hurt, terribly, every little bit of it. Maybe she had the flu. Maybe she had caught it from Dickie.

Dickie. Something had happened to him. Something.... Jennie had been having a nightmare. Something about black sticks, and the devil, and rats in a sewer....

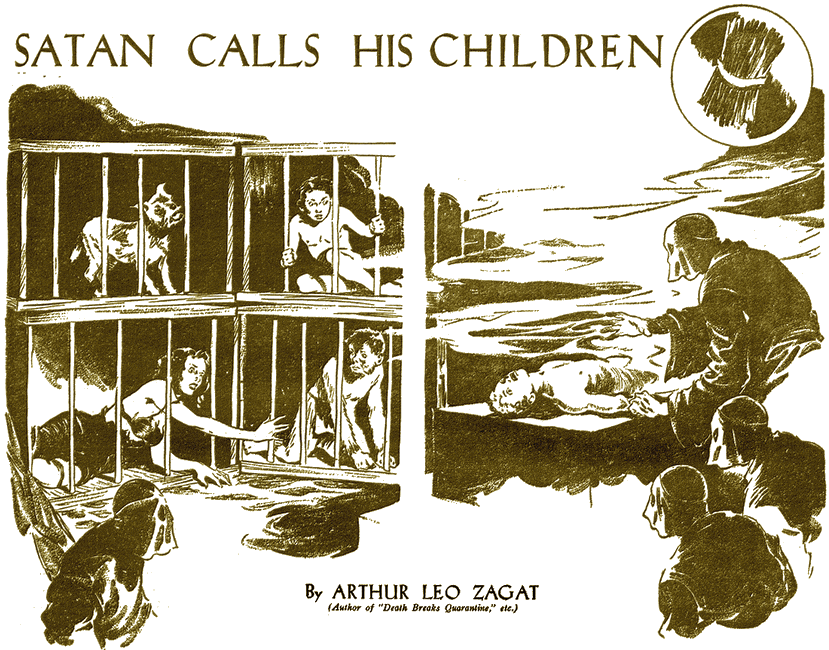

What...? It was a wooden ceiling Jennie's head had bumped against, close over her head. The black stripes were rusty iron bars, framed in a panel, hinged and held closed by a big padlock. Jennie was in a cage!

The cage was so small that there was just about enough room for her to lie outstretched. A blue light came from a fire down there in the middle of a stone floor that was about three feet below the bottom of the cage.

It was a bundle of sticks that burned with that strange blue flame, a bundle of black sticks! They were bigger, each about the size of Dickie's baseball bat, but otherwise they were exactly like the sticks in the little fagots she had been seeing all day.

The blue light reached out from the blue fire and flickered on rows of big stone pillars, streaked with damp and black with age, whose tops joined in stone arches on which a stone ceiling was laid. The blue light reached behind the pillars and danced on tiers of iron-barred cages like the one in which Jennie was.

The cages were like shelved bins piled on top of one another. And there was movement inside them.

Jennie became conscious of small sounds in the room. Maybe they had been too small to hear before. Maybe her hearing had come back more slowly than her sight. But she heard the sounds now.

They were the pad, pad of small soft feet. They were the whimpering of small animals. They were a low moan.

The fire flared higher. The blue light was brighter, bright enough to reach into the cages, bright enough to show Jennie what moved in the cages.

There was a grey dog in one of them, loping back and forth, back and forth. In the next another small form prowled back and forth. But this wasn't a dog. This was a little boy.

It was Carlo Gorgio! The fire died down again just as Jennie saw Carlo, and she could not be sure, but it seemed to her that his little arms and his little legs were black and shaggy, as if they had fur on them.

When the fire flared up again Jennie wasn't looking at that cage. Her face was shoved against the bars in front of her and she was looking at others.

There were children in some of them and there were dogs in others. Jennie didn't look long at any one of the cages. Her staring eyes were going along the long tiers, faster and faster.

She was looking for Dickie. Her eyes went along the cages and reached the stone wall at the end of the room, and she hadn't found Dick. She stared at the wall, and at the high, wide door in it that was stuck full of rusted rivet-heads and bound with rusted iron straps, and she was trying not to hear the voice that was whispering inside of her skull.

"You've seen him but you didn't know him," the voice was whispering. "Remember the picture in Mr. Erlauber's book? Dick is like that now. He has been changed into a dog!"

JENNIE'S hands closed on the bars of her cage, and

she tried to tear them apart. They didn't move, but the

rust on them cut into her palms, tearing her skin. The pain

of that ran up Jennie's arms to her brain and it silenced

the whispering voice, clearing her brain.

She hadn't seen all of the cages. Some of them were on her side of the room and some of them were behind pillars so that she could not see into them. Maybe Dickie was in one of those. Mavbe if she called to him...?

Then a scream ripped out—not exactly a scream. It was the shriek of that great door's rusted hinges, and the door was swinging open.

It might be a scene out of hell itself that was framed by that stone arch. Within a semi-circle of blazing fagots an appalling apparition stood, red cloaked, red hooded, red hand upraised. Before him a waist-high platform was swathed in red draperies and past that, past the curve of the blue fires, Jennie saw a cluster of people who seemed to have been about to surge forward and been stopped by that threatening hand.

She made out men and women there, all of them rigid, all held motionless as if by the paralysis of a nightmare, their faces ghastly with the blue light upon them and ghastlier still with a strange mixture of blind wrath and blind terror. Beyond them the wavering light was swallowed by darkness into which Jennie sensed space stretching endlessly away.

The door swung wide, showing the person who had opened it. This one, too, was cloaked and hooded, but in dull black. Grotesquely misshapen, he seemed the shadow of some delirium that had taken material form to serve as Satan's acolyte.

"You are those who have defied me because you have come far from the forests of the Ob and have forgotten the power that is mine this night."

The black figure moved into the room and passed out of Jennie's sight behind a pillar. A key scraped in a rusty padlock.

"I shall prove to you that I still have that power." The devil's disciple came into sight again going out through the doorway. His back was to Jennie, but it seemed to her that he was carrying something. "Before your eyes I shall prove it."

He moved aside. Jennie saw what was on the altar. She saw a small boy's form, bound hand and foot, and gagged. She saw a small head capped by blonde, clustering curls.

She had found Dickie!

Before the scream that tore at Jennie's chest could tear free, before her bleeding hands could begin to shake the bars they still clutched, Satan's arm swept out in a circling gesture above the dais. The fiery arc exploded in a sheet of blue flame, blinding her, blinding all human eyes in that cave of hell.

The glare filled the cavern and was gone. Then indeed a high, shrill shriek ripped from Jennie's throat, a scream of anguish that cut her larynx with its knife-edge. But it was only one thin thread in the pandemonium of the mad dog's howling, of the screams of those others who had witnessed that incredible thing.

On the red bed of Satan's altar a small, bound thing writhed in agony. Not Dickie. It was a dog, a yellow-furred little dog from whose bandaged jaws the foam of madness frothed.

ABOVE the screams and the dogs' howling and the deafening clangor of the cage doors at which the dogs plunged, a triumphant laugh boomed out, hollow and humorless and gloating. It was Satan who laughed, but it was his grotesque acolyte who lifted the little yellow dog, its jaws still bound, and shambled with it into this inner chamber.

Jennie saw the gaunt small form twist, hanging from gross hands by the scruff of its neck, and then the pillar hid it.

"Dick!" she whispered, robbed of her voice by the screams that had torn her throat to ribbons. "Oh Dickie." Her hands slipped from the bars, exhaustion numbing them, as the black being reappeared, shambled out through the great door and tugged it shut upon sight and sound beyond it.

Jennie lay whimpering on the floor of her cage, her brain no longer working. And suddenly she was very still. Something had stuck her, just below the waist. It was sticking into her now. She knew what it was. The point of the nail scissors she had stuck into a pocket of her skirt and forgotten.

Slowly, stealthily, she fumbled her fingers into that pocket and fumbled the scissors out of them. They were of good strong steel, and the points were narrow. They were narrow enough to poke into the keyhole of the padlock and to work around inside it.

If the padlock was not old and rusted it could not have happened. Even then it needed something else. Luck, maybe. Anyway, the points of the scissors caught on something inside the lock, and there was a click and it sprang open.

Jennie climbed down to the floor, swayed a minute against the wall of cages, and then started moving. She went along between a line of pillars and the cages till she came to the last of the great stone columns, and there she stopped.

The yellow dog lay on its side against the bars of the cage at which she stared, its jaws freed. It saw her and its moaning stopped, but its flanks kept heaving and its eyes were balls of red flame.

"Dickie!" Jennie whispered, her hands going to the rusted padlock with the scissors. "Little brother...." The padlock clanged against the iron frame. The dog rolled, was on its feet, was leaping at the bars. His hot muzzle struck Jennie's hand and if she had not snatched it away his foam-covered fangs would have sunk into her flesh.

He fell back, haunched, snarling. In that instant Jennie remembered Maria's words, "I no can buy heem from Satan so I geeve heem back to God", and they had a new and terrible meaning. Baby Andros was dead and at peace. Dickie was doomed to live on, a dog, a rabid dog!

He sprang! Swift as light Jennie's hand darted through the bars to meet that lunge. The scissors in it plunged into the dog's throat, and ripped....

THE small yellow body pounded down on the cage

floor. Blood gushed from the torn throat. Jennie stared

at the furry little form that was so still, so dreadfully

still. "God take him," she prayed. "God rest him." Then

she looked at the bloody scissors in her torn and bleeding

hands, and she prayed, "God have mercy on me." Her left

hand went to her neck, ripped away the neck of her waist so

that there would be nothing to interfere with the steel.

Her right hand came up slowly, its fingers gripping the

scissors....

"Jennie. Mees Jennie."

The thin, piping call came from a cage on the other side of the chamber. Carlo Gorgio was crowded against its bars, his small hands thrust through them, pleading.

"Take me out from here, Mees Jennie."

Jennie realized what she had been about to do, and hated herself for it. She had thought only of Dickie and herself, that she had killed Dickie and that she wanted nothing more than to follow him to wherever he had gone. She had forgotten that there were other children here, children who had not yet been damned by Satan. She must save them. She would get them out of their cages and somehow she must find a way to get them away.

She went across the stone floor, went past the blue fire.... A squeal jerked her head around!

It was the rust-frozen hinges of the great door that were squeaking. The door was opening! Thick hairy fingers curled over its edge, the fingers of Satan's assistant. He was coming in for another victim! If he saw her...!

Terror twisted in Jennie's breast, roared in her ears. She whirled, saw that the blue glow did not quite reach the other end of the chamber, darted towards it. If she could get to the shadows before the door came fully open, hide there, he might not notice her empty cage.

The hinges screamed as the door moved faster. A blank stone wall rose in front of Jennie. She stopped herself with her hands against it, went down to her knees, cowering in the shadow which was not dark enough to hide her.

She heard the rasp of shambling feet on the stone, moving toward her. He was coming, he had seen her and he was coming for her, slowing, inexorably, sure she could not escape him. The sound stopped!

Jennie made her head turn, made herself look behind her. She saw a black, grotesque form silhouetted against the green-streaked grey of the closed door. The black hood was turning about, hesitant as if the eyes hidden within it were scanning the cages, momentarily uncertain which one to choose. They had not spied her! She was still safe. She still had a chance.

The invisible head nodded in decision and the grotesque body it topped got into motion again. Jennie strained to see which cage it approached, made out within it the russet curls of Marta, the little girl whom she had last seen in Zbick's grocery with Rivcha Chesny's protecting arm around her. Marta was to be the next....

Stones scraped behind Jennie! The noise was terribly loud and the devil's servant heard it. He came around to it. He saw Jennie. His bellow of rage filled the chamber and he lurched into a shambling run toward her.

THE fire threw his shadow before him, a grotesque

blackness darting ahead of him. It reached her and she

screamed, coming up to her feet, her back against the wall.

The gigantic figure plunged toward her. The wall was behind

her. There was no escape.

A hand grabbed her shoulder, pulled her sidewise and back—back through the wall itself! "Jen!" Someone yelled in her ears. "Get down that ladder, quick!" It was Bob's voice that yelled! It was Bob who had pulled her back with him through an opening in the wall that had not been there a second before. He was filthy with green slime, his face was a pale staring oval in the dimness, and his hand was at the pocket of his mackinaw, pulling at the butt of a gun.

They were on a shelf-like ledge, and behind Bob a circular black pit yawned, the ends of a ladder's uprights jutting out of it.

"Quick!" Bob yelled again, and Jennie went over the edge of the pit.

Then a shadow blotted the blue glow coming through the opening in the wall above. The black fiend's bellow blasted down to her. She looked up.

Bob's hand wrenched at his pocket. Cloth tore and his hand came free with his gun. Too late. A black shape lurched through the hole in the wall, bellowing, smashed into him. The two merged into one swaying mass, up there.

Metal flashed, streaking down to Jennie. Bob's gun hit the ground at her feet. She bent to snatch it up.

Wood smashed. Broken wood of the ladder sliced her arm. A whirling huge mass hurtled down, pounded into her, knocked her down. She slid down a steep, slime-slick slope and behind her there was a roar, cut off by a gigantic splash.

Jennie dug knees, elbows into the stone on which she was sliding, braked herself to a stop. She twisted to look behind her.

Far behind, and above her, a blue radiance one shade better than darkness glowed about a monstrous black blotch crouched beneath the aperture through which it came. From just beyond it came the slow plop, plop of bubbles breaking the surface of a pool thickened to soup by the things that had rotted in it.

Those bubbles came from Bob's lungs. The monster had landed safely and Bob had fallen into the pool. He was drowning there.

Something hard hurt Jennie's palm. It was the gun. She still had it. Her teeth bit into her lip and she lifted it. There was no grief, no despair in her brain. There was only the thirst for vengeance.

She pulled the trigger. Nothing happened. Nothing at all....

The dark shape moved, up there! He had sensed her! He was coming after her! Panic ran icy through Jennie's veins. She started to jump up.... Her feet slid out from under her and she pitched down the sharp slope She went straight down, suddenly. Thudded into something soft and cold.

JENNIE fought erect somehow, but there was water

about her ankles and mud under the water sucked at her

feet. Somehow she got moving, kept on moving.

After a long while it got colder, and a little lighter. Jennie kept on. Sometimes there was mud sucking at her feet, and sometimes there was hard ground, or ground neither hard nor soft, but slippery, so that she fell to her knees. When that happened the black flame of terror leaped high within her, and her arms would flail around till she got hold of something by which to pull herself up.

All of a sudden the black wall wasn't at Jennie's left any longer. There were lights instead, spreading on the surface of a muddy flat that stretched between them and her. Jennie realized that the blackness of terror and despair had seeped somewhat out of her brain. She realized that the lights she saw were the lamps along the cobbled width of Eastern Avenue, the waterfront street that by day was alive with trucks and shouting men, but now was deserted and silent as the grave.

Jennie knew then that she somehow had gotten to the river, that the wall that had loomed above her was the end of a half-block wide wharf. But she did not know how long she had been struggling through the tunnel, and the muck and mire of low tide. She did not know how far she had wandered in a daze that was close to madness.

She still was not thinking very clearly, but she knew dimly that she must get out of the river. She resumed her painful progress, forcing her tired legs to carry her to those lights, dragging herself along the side of the wharf, past whose corner she had come. Just as she got to the wharf's street-end her left hand lost its hold on a broad bollard and she brought over her right to help it. Something hard in her right hand thumped against the wood.

It was a revolver. It was Bob's revolver. Somehow she had held on to it through her daze. This was the gun that had failed her, back there in that fetid tunnel. She started to throw it away—then paused.

There was light here, and she saw why it had misfired. A bit of green slime, something that had not quite rotted away, was tangled in the hammer, had jammed it. Jennie picked it out with trembling fingers, not knowing why she expected yet to have use for this gun.

Then she knew. She heard the melancholy howl of a dog. She had heard that in her delirium, but she had not imagined it. One of Satan's mad dogs was free.

Jennie crouched against the bollard, hidden by its wide girth, and waited for the dog. It howled again, much nearer, and now she heard the patter of its running feet. It was coming toward the river, down the street the corner of which she could just see, and it was coming fast. There was the sound of other feet too, the pounding of heavy feet, of Satan's black servitor of course. He had set the dog on Jennie's trail, was hunting her down.

A WOMAN appeared out of an alley between two of the

warehouses that lined the other side of Eastern Avenue. The

lights of the corner street lamp took her, and Jennie saw

that it was Rivcha Chesney.

Rivcha looked about her and called out, in a plaintive voice. "Marta!" Her voice was husky, as if she had been calling for a long time. "Where are you, Marta?" The dog's howl was appallingly near. Jennie's mouth opened to call to the shawled woman, to tell her where her little girl was. But just then the dog howled again, and it came around the corner into the light.

It saw Rivcha Chesney, stopped abruptly, swung around to her. It hunched, growling, its eyes red balls, its fangs dripping foam. The street lamp shed its light on the dog's fur, and it was russet, red as Marta's hair had been.

Rivcha's arms flung out. The dog leaped, its white fangs gleaming, straight for her throat. Then orange-red flame lashed through the dimness, a shot blasted the silence. The dog's body struck the woman's shoulder, jolted from its course, fell to the sidewalk. Writhed there, yelping.

It wasn't Jennie who had shot. She had not dared, she was no marksman. It was a policeman who had pounded around the corner at that last instant.

"Mad dog," the policeman yelled, his face abruptly white. Rivcha was down on her knees on the sidewalk. She was gathering the wounded dog in her arms. "Don't!" The cop yelled. "That dog's mad."

"Eet ees Marta," the woman wailed. "My Marta," and hugged the bleeding, furry body to her breast.... The dog's head snapped up. Its teeth drove into Rivcha's throat, clamped shut ....

"God!" the cop blurted. "Batty. Batty as a loon."

OTHER cops crowded around the dead woman and the dead dog. People too, crowded around them, sprung magically out on the deserted street as crowds do in the city when anything happens. Jennie watched them from the concealment of the bollard, watched for a chance to slip past them unnoticed.

She didn't want them to see her. She didn't want them to ask what had happened to her, why she was torn and soaked with the slime of the tunnel and the muck of the river. She had something to do, and she was going to let no one interfere with her.

"Batty," the cop had called Rivcha, who had gathered her dying daughter into her arms. Batty they would call Jennie if she told them about Satan and how he turned children into dogs. But she knew it was true. Dickie was dead, and Bob was dead, and only vengeance was left to Jennie, but that she would have.

She could not find her way back to the tunnel. Its entrance was somewhere along the river front, but she had no idea how far she had come from it. But she had read the street sign on the lamp post, Hogbund Lane, and all of a sudden she knew how she could find the chamber where Satan was.

The dog, Marta, had escaped from there, beyond doubt, and she had run down Hogbund Lane. The Byzantine Church was on Hogbund Lane. Papa Anton's church! Jennie recalled how Papa Anton had stopped her from telling about the sticks that afternoon, how right after he had heard her start to talk to Mr. Erlauber about them, the warning fagots had appeared on the floor of her flat. Papa Anton had been in Mr. Erlauber's store, had heard her tell her story to the old German, and at once after that Dickie's bell had rung and Dickie had been gone.

Maybe Satan let Papa Anton keep the money people would pay to keep him from turning their children into dogs. Hadn't both Maria and Sonia Gorgio said something about buying their kids from the devil? None of the Sylvanians had much, but there were many of them and a little from each would make a lot of money.

Maybe Papa Anton was Satan.

Whatever he was, Jennie had figured out that if she found Papa Anton she would find the key to the mystery. She saw her chance to get across Eastern Avenue unseen. Minutes later she had made her way, keeping in the shadows, up Hogbund Lane to the Byzantine Church, and was crouched in the darkness against its wall, waiting for a peddler to drag his empty pushcart past her along the sidewalk.

She was in the angle between the steps leading up to the wide, high door of the church, and its wall. Ten feet above her a small window was lighted, and its yellow oblong was the only light in the block except for the street lamps.

The wall was of rough-hewn stone. Her toes just could catch in the spaces between them. Any other time Jennie would have been afraid to try climbing that wall, but there wasn't any room in her pounding skull for that kind of fear. There was room only for the idea that had brought her here. She was more than half mad, and surely there was reason enough for that in all she had gone through.

She went up that wall like a cat climbing a backyard fence, using only one hand because the other held the gun. Her knees came up on the wide sill. She peered through the window.

The room she saw was like an office, its walls bare except for a couple of framed pictures on it, a desk in its center. Seated at that desk, his back toward her, was Papa Anton, in his black cassock. Jennie could see his hand. There was something in it—a tiny bundle of black sticks, bound by a bit of grey fur.

JENNIE tried the window sash with her free hand. It

moved up a little, quite without sound. Her fingers slid

in under its lower edge and then, in what seemed like one

motion, she had flung the window up and jumped through it

into the room. Papa Anton must have heard the thump of her

landing, for he jumped up and whirled around, his chair

crashing to the floor.

"Keep back," Jennie exclaimed shoving the gun at him. She must have been a weird spectacle, covered from head to foot by slime and river muck. "Keep back or I'll shoot."

"Retro me, Sathanas!" the black priest exclaimed. His hand flailed from behind him, hurled an inkwell at Jennie's head. She dodged it, her gun going off, thunderous.

Papa Anton jolted back against the desk, and then he was sliding down, his black cassock suddenly blacker over his breast with a glistening wetness that spread rapidly. He went down like a ripped doll out of whose body the sawdust was running, and settled limply on the floor. His face got grey, above his black beard and his eyes widened with pain.

Jennie wiped her hand across her face, in an unconscious gesture of revulsion at what she had done. Unconscious because as far as thought was concerned she was glad, glad that she had killed Satan.

"You..." Papa Anton gulped. "You. I did not think... that you too... were plotting... against my people."

"I... What do you mean?"

"The ancient... superstition of Satan's... Night.. The fagots... driving them mad... with fear. I traced them to...." His grey lips writhed. For a moment he could say no more.

What was he saying? Was he trying to tell her that someone else was Satan? But he was lying. He must be lying. Of course. He didn't know he was killed. He was trying to throw the blame on someone else. But before he died she must find out where the cages were. Maybe there were still some children there, unchanged.