RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

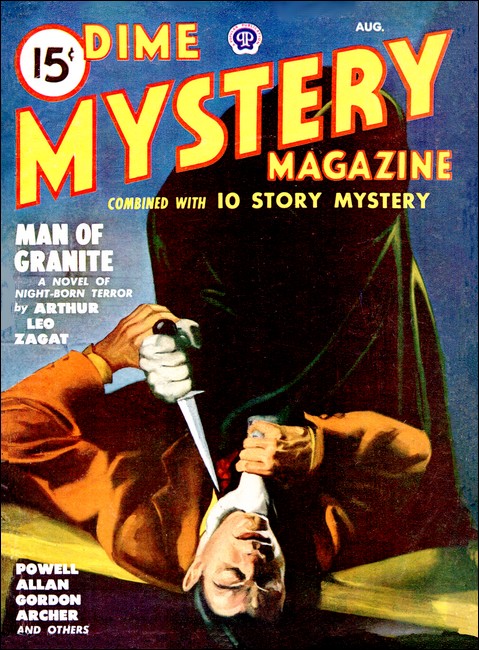

Dime Mystery Magazine, August 1948, with "Man of Granite"

It was a dream, Morgan had said, only a dream.... But, Dear God—what kind of dream was this... this great stone figure that stalked the miasmic night with ponderous tread... and pounded his granite fist on Morgan's own door?

IT wasn't being alone in the house, except for the baby, that made Arlene Morgan uneasy. She'd done a lot of baby-sitting since her sixteenth birthday, last May, and she'd gotten used to the silence of an empty house and the noises within the silence: old wood whispering to itself, scurryings inside ancient walls, ivy rustlings against windows dark with night.

If she was a little jittery going upstairs to make sure the baby was dry and covered, it must have been on account of the queer thing Mrs. Vandahl had said just before she left "Take good care of my little Lenny," she'd said, pale and great-eyed in the doorway. And then she'd said slowly, "Intermit no watch."

Arlene wished now that she'd turned on the light down there in the foyer. She hadn't because she didn't need a light just to go upstairs in this house. She'd practically lived here up to when, last year, the Fosters sold their farm to her Dad, and the house, furniture and all, to the Vandahls. It was nearly five miles to her own home by the road, the way it meandered, but cutting through the woods it was less than two. Jimmy Foster and she, neither of them having brothers or sisters, had grown up together.

The room she went into, halfway down the dark upstairs hall, used to be Jimmy's. In the dim glow from a tiny light on the dresser it was almost the same as when Arlene used to look at Jimmy's stamps here, rainy afternoons, or his birds' nest collection. The biggest difference was the crib where a bed used to be.

The baby was all cuddled up in the crib, fast asleep and smiling. He had a round and chubby face and two dimples in his fat cheeks, and wisps of blond hair curled like silk on his pink, clean scalp.

She stood there a moment, her dark blue slacks and blue sweater clinging to her sturdy figure. "Sleep well, Lenny," she whispered. She tucked the blankets in around him, touched his warm cheek with a light fingertip and tiptoed out.

At the foot of the stairs the big front door loomed darkly in the seep of light through the portières curtaining the parlor archway. Arlene remembered how Mrs. Vandahl had shaken it to make sure it was locked after she'd closed it from the outside. She'd told Arlene not to open it for anyone, no matter who. And then she'd said, with a strange, lost smile, "Take good care of my little Lenny, Arlene. Intermit no watch."

In the dark and empty house, it had had a terrifying sound.

ARLENE reminded herself now that she had homework

to do. She took her school bag from the marble base of the

hat rack on which she'd hung her coat and went through

the heavy, fringed portières into the parlor. It

was light in there. The green plush sofa and the deep,

comfortable chairs stood in exactly the same places on

the Wilton rug Arlene remembered so well, and the same

brocaded drapes hid the two wide windows that looked out on

the porch. It was warm in the familiar room and Arlene's

uneasiness left her.

Going to the carved oak desk, nearly black with age, that stood against the wall opposite the windows, she pushed aside a book that lay open on it, put her bag down, pulled up a chair and got out her algebra book and notebook, and a pencil.

She did her algebra problems and her history assignment. She had a scare when she couldn't find her Greenough's Latin Grammar in the bag, but when she dumped everything out on the desk, she saw that she did have it.

She ought to pack her bag so it would be ready when Mrs. Vandahl came home, she decided. She put in all her books except the Greenough and then picked up her gym bloomers. They'd fallen across the book that had been there, lying open, and the title printed across the tops of the pages caught her eye. Paradise Lost.

That's by John Milton, she thought. We're going to have it in English next term. It looked like a school book the way every tenth line was numbered down the margin so teacher could tell you what lines to read. Maybe it used to be Jimmy Foster's. Maybe it was Jimmy who'd underlined in pencil that passage on the right- hand page.

Arlene started to read it and Mrs. Vandahl's strange words leaped out at her:

... intermit no watch

Against a

wakeful Foe, while I abroad

Through all the coasts of

dark destruction seek

Deliverance for us all....

No, Jimmy Foster hadn't underlined these words.

They'd been marked, the book left open here, as a warning

to Arlene.

The silence of the house closed in on Arlene. A rattle of plaster falling inside a wall abruptly was sinister. The rustle of ivy against drape-swathed windows was a fumbling of furtive fingers.

She was being silly. She was imagining things. Her throat locked on terror then. Imagination?

The thud of a heavy footfall on the porch outside those windows was not imagined. Arlene heard another, a third, a fourth, advancing, slow and ponderous and infinitely menacing, across the porch.

And now the door shook to the blow, as if of a fist of stone, that fell upon it.

JOHN MORGAN shoved his reading glasses up on his

seamed forehead, rattled his newspaper irritably. "What the

devil's got into you, Mary?" he demanded. "Way you've been

staring out of that window the past half-hour, a fellow'd

think this was the first time Arlene's been out late,

baby-sitting in a neighbor's house."

"It's the first time she's been sitting in that house." Her frail form taut in the curtained embrasure from which one could see a little way up the road towards the Foster house, his wife did not turn. "And I'd hardly call Lorna and Martin Vandahl neighbors."

"Why not? They live in the next house to ours, don't they?"

"That's about all they do, too, John—live there. They've had nothing to do with anyone since they first came here, and they've made it plain they don't want to. Nobody knows anything about them, not even where they came from. They never go anywhere, never get any letters—"

"She did," Morgan grunted. "This very morning. Jed Parker showed it to me when I met him at the gate just as he was about to put our mail in the box."

His wife turned around. "Where was it from?"

"We couldn't tell. There was no return address and the postmark was smudged. There was just her name, typewritten: Mrs. Lorna Vandahl, RFD 3, Montville."

A knot cracked in the fireplace and shot sparks against the hearth screen. "Must have been that letter took them out," Mary mused. "About an hour after Jed passed I saw them drive past and a little while later she came back without him, just the baby bundled up in the seat beside her. She would have had just enough time to put him on the 10:04 to the city."

"Suppose she had." Morgan lowered the newspaper to his lap. "What of it? And if you don't like them, why let Arlene go there in the first place?"

"I couldn't tell the child no, John, when Mrs. Vandahl called up and said she had to go somewhere for a while and didn't dare take the baby. Dare, she said!"

"Oh, for the love of Mike," Morgan growled. "Of course she didn't dare take the infant out of a warm house into the night cold." He pushed up out of his easy chair, strode across to his wife.

"Look," he said. "You're imagining things. There's nothing queer about the Vandahls time won't cure. They're just city people who aren't used to being neighborly. Besides, they're old, and they're set in their ways."

"They are old, John. Especially him, with his hair all white. He seems almost too old to really be the father of an infant like that."

"Maybe they adopted it," Morgan said. "Either way, I don't give a hoot. All I want is for you to quit fretting about Arlene. That woman promised she'd bring her home by ten and it isn't—"

The grandfather clock's deep chime, welling in from the front hall, cut him off. "There it is," she said. "Ten o'clock, and no Arlene."

"Okay." Morgan shrugged. "You won't give me any peace till I go get her, so I might as well go now."

Buttoning his lumber jacket as he strode across the porch and down the steps to his parked car, Morgan was aware of a sense of urgency he would not for worlds have admitted to his wife.

He slammed the car door, drove out the gate and onto the road. Lit by bright moonlight, the road curved in a wide sweep along the brush-grown fence that marked the limit of Morgan's land and then past the rustling dark loom of the woods. The sharp late November chill was tangy with the fragrance of the pines as the road reversed its curve and the woods retreated. He strained his eyes ahead, but the road was empty all the way to where he now could see the old Foster house silhouetted blackly against the luminous sky, the moon glistening on its panes.

His eyes opened wide with shock then. Those panes were orange red! In the next instant flames exploded from them, swirling together into a single appalling mass that burst into the sky, a pyre from which no one could escape and in which no one could live.

THE shock of that sudden holocaust brought Morgan's

heel hard down on the brake pedal. Locked tires screamed

on macadam and the car bucked to a halt. As he stared at

the blaze he seemed to hear Arlene's cry for help. "Dad!"

He heard it again, "Dad!" so clearly that he looked around

as if he actually could see her, miles away. He did see

her.

He saw her stumbling out of the woods that edged the narrow field beside which he'd stopped. "Wait!" she called, stumbling toward him. "Wait for me, Dad," and a thin wail threaded her call, an eerie sound in the frightened night.

In a moment he was out of the car and running across the field to her. She was carrying a great bundle in her arms, and Morgan realized vaguely that the wail come from this. He reached her and flung out his arms toward her but she evaded him, half laughing, half sobbing. "Watch out, Dad. You'll make me drop Lenny."

Morgan looked down. "It's a baby," he muttered stupidly. "A baby."

"Of course it's a baby, Dad. It's Lenny Vandahl and he's awful cold." But it was Arlene who was cold, her teeth beginning to chatter, her lips blue. Her school bag hung by its strap from her shoulder but she had no coat on.

In the car, she snuggled under the robe he put about her, closed her eyes and sighed. As the car lurched underway and gathered speed, a hollow-moan rose in the far distance, the Montville fire siren, calling out the volunteers.

Arlene stirred. Without opening her eyes she murmured, "Wonder where the fire is."

"Don't you—" Morgan caught that back. She didn't know or she would not have said that. Someone else, seeing the red glow in the sky, had sounded the alarm.

What then had she been fleeing from?

"Arlene," Morgan asked, "why did you run from that house, carrying the baby?"

"The—the Wakeful Foe. It was banging on the door." Remembered terror had her trembling again. "I grabbed my school bag and ran out in the kitchen and up the back stairs to the baby's room and I heard it on the stairs, coming up."

"It?" he broke in. "What? Some animal?"

"No. But not a man either."

"Now, dear, it has to be one or the other."

"It wasn't," she insisted. "I saw it. It was in the hall when I came out carrying Lenny and I saw it plain. It looked like the snow men Jimmy Foster and I used to build, all clumsy shaped, its body and head all round and lumpy. Only," she said, "it wasn't made of snow. It was stone, Dad. It was all chopped out of grey stone."

"Stone? How could it be stone? It was alive, wasn't it?"

"It was alive but it was stone. I felt it. I was so scared I couldn't run, and it thudded towards me and just as it almost reached me I turned and ran. But it was so close it touched the back of my neck and I felt its stone hand scratch me. Look."

Arlene bent her head forward and her father looked down at the back of her neck and saw the scratches, the scrape rather, exactly like stone would make rasping tender skin. His lips parted but no sound came from them as his daughter went on. "I ran. Lenny was awful heavy but I ran down the hall and down the back stairs and out the back door into the woods. It followed me. I heard it behind me in the woods but I ran fast and pretty soon I didn't hear it any more."

The fire siren was a banshee howl in the night. Morgan made himself speak calmly, "You got that scrape from a branch in the woods, dear. You dreamed the thing in the house and you were all mixed up." That was it, of course. "You see, it's the Foster house that's on fire. You smelled smoke in your sleep and dreamed this stone thing and you were so scared it seemed real."

"I didn't dream it, Dad." Her small voice was very certain. "I felt it and I saw it and it was stone. There were even little shiny places where pieces had just been broken off it."

The night was alive with the howling siren, but Morgan was aware only of his daughter's eyes, pleading for belief. A leaden weight formed at the pit of his stomach.

There is a name for the mind that cannot distinguish reality from dreams.

A BLACK sedan rushed past them, and then the Larsens' pickup truck. Turning in at his own gate Morgan saw the front door open and Mary's shadow appear on the porch as she came out "Listen, Arlene," he said. "Maybe you did see this thing, but I don't think we'd better tell mother about it. We'll just tell her you grabbed up the baby when the fire broke out and ran out with him just as I came along. Understand?"

"Yes, Daddy," she agreed. "It would frighten mother."

Then he was braking and Mary was beside the car, opening the door. Oddly, she did not seem surprised that Arlene should hand her the baby to hold while she climbed out. Even when he told Mary the story they'd agreed on, her only reaction was to give the infant back to their daughter and say, "Go inside and get warm, dear. I want to talk to your father a minute."

Arlene went off obediently. The fire engine from Montville thundered past. As its roar faded up the road, Mary said, "Cal Hutson phoned just now."

"Huh?" Hutson was the marshal of Montville township. "What did he want?"

"He asked if our Arlene was over at the Vandahls, sitting with their baby. When I told him yes and that you'd gone to get her, he said I should call there and tell you not to wait for them to come home, but to bring the baby here to me. Because, John, about two hours ago they were killed in their auto, just this side of town."

"Good Lord! How did it happen?"

"Cal said their gas tank exploded and burned them to a crisp. The only way he could tell who they were was by the license plate number and the State Bureau was closed, which was why he was so late calling. He said they thought at first the car might have hit one of those low trailer trucks from the quarry but no one remembers one passing through this evening."

Morgan asked, "Why did they think the Vandahls had hit a quarry truck?"

"Because there were some pieces of grey stone in the road that looked as if they'd just been broken off from something." Mary apparently did not hear his gasp because she went on, "I was just about to hang up when I heard the siren start, and then I heard your car coming so I didn't have to phone."

He had to get away before she saw the look in his face. He put the car in gear. "I've got to go help fight the fire," he said hurriedly. "I'll be back soon." He was moving before she could get out a word in answer.

He sent the car roaring out into the road again but as the fences started to slide by he slowed it, trying to think. There couldn't, he thought, be any connection between the bits of stone at the scene of the accident and the stone monster Arlene had dreamed about. Even if there was, even if she hadn't dreamed the thing but had actually seen it, no one would believe that she had.

She's a child, he thought. She'll tell about it to some friend and then it will spread. If he were not her father, might he not himself suspect that she'd set fire to the house and invented the monster to explain it?

Or, at the very least, that it was an hallucination of a weakened brain? Somehow, somewhere, he must find incontestable proof that Arlene had told the truth, incredible as it was.

By now he'd come to the curve from which he could see the Foster house, and even from this distance he could see that already it was a mere skeleton of black timbers outlined by the still-burning fire. He recalled Arlene's saying that she'd heard the thing follow her into the woods. That was where he must look for traces of its existence.

Morgan ran his car off the road. Then, taking a flashlight from the glove compartment, he got out and went across the field in which he had found Arlene. The moonlight was strong enough, here at the woods' edge, so that he did not need the flashlight to locate the path by which she'd run from the Foster house.

He saw where the carpet of dead leaves had been disturbed by her feet.

He plodded into the woods, the leafy carpet rustling. The pines grew more closely, blocking out the moonlight, and he switched on his flashlight to follow the path. It revealed only the single track left by his daughter's saddle shoes as she fled the Golem...

He stopped short, the hairs bristling at the nape of his neck. From where had that word popped into his head, that name for a monster of stone, 'all clumsy shaped, its body and head round and lumpy,' instilled with life?

He remembered. Vividly he remembered a scene out of his forgotten youth: A beamed lecture hall. Rows of chairs rising tier on tier from the dais where Professor Janely droned to his audience of drowsy, half-attentive students.

"Mary Shelley," Janely was saying, "may have gotten the inspiration for her famous tale of Frankenstein's monster from the medieval legend of the Golem." Morgan seemed to recall his words verbatim. "In Frankfort, Germany, somewhere around the turn of the twelfth century a certain student of the Caballa, the Hebrew lore of ancient magic, is said to have hewn out of stone a rough and clumsy figure of a man and by the use of forbidden rites to have given it life.

"The Golem's first act was to crush its creator's skull with a single blow of its granite fist. Freed thus from control, it proceeded to terrorize the Ghetto, night after night, until at long last the Chief Rabbi found in his tomes a charm by which it could be imprisoned. Only imprisoned. The legend asserts that once having been given life, the Golem is immortal."

Abruptly then, Morgan was back in the dark woods, his heart pounding. Staring into the shimmering blackness he seemed to see—he could not be sure—just beyond his flashlight's reach a shadowed figure that did not move.

Then it was gone. He must have imagined it. His probing beam found only gnarled boles, winter-naked underbrush. It returned to the path and he was moving again. Then he halted once more.

The bright end of his torch beam had touched shoes, motionless on the dead leaves. It lifted, brought out of the darkness trouser legs scarred with burned holes, a grey topcoat also burned. It found a narrow, gaunt face so blackened with soot that it seemed to be a mask.

One of the fire-fighters, of course, wandered off from the blaze, but who in the township had hair so startlingly white? Only the man Mary had just told him had died tonight, ten miles from here. The words came slowly off Morgan's tongue. "Who are you?"

"Vandahl," the answer came. "Martin Vandahl. You're John Morgan, aren't you? I'm on my way to your house." Morgan didn't get a chance to answer, though. For, from behind him, a giant fist pounded the base of his skull and clubbed him into oblivion.

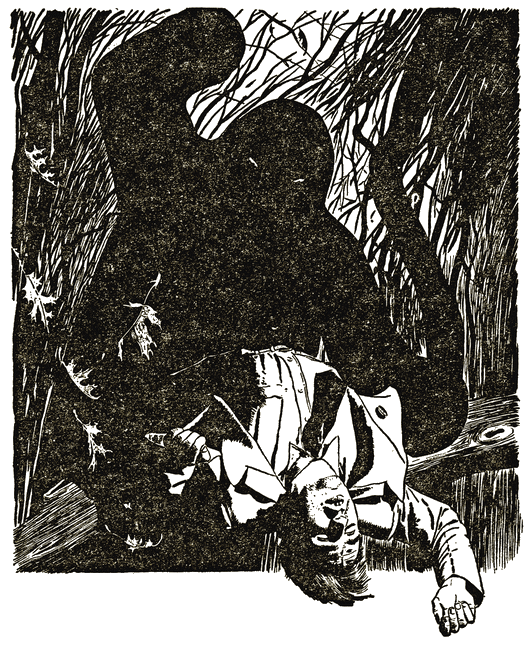

Human or monster, Morgan didn't know. All

he knew was that a

giant fist had descended on him,

clubbing him into oblivion.

STARTLED awake by her daughter's frightened cry

from above, Mary Morgan sprang out of the chair in which

she'd been dozing and ran upstairs.

Moonlight was strong in the room as Mary entered. Arlene was sitting up in bed, staring dazedly at her. "What's the matter, darling? What's wrong?"

"I can't find Lenny." The girl's sleepy voice was despairing. "I've looked and looked all through the coast of dark destruction and I can't find him."

"He's right across the hall, dear, in the spare room." Mary's tone was steady, comforting. She reached the bedside and put a palm on the girl's forehead. "You've had a nightmare." The smooth skin was cool to her touch. "I'm not surprised, what with all you've been through, but lie down now and go to sleep."

The girl sank back on the pillow, her throat pulsing where the flannel nightgown left it bare. "It was awful, mother. I was looking and looking for Lenny and there was no light, not even stars, and I couldn't hear anything except the wash of waves on the coast, and I knew the Wakeful Foe was looking for Lenny too. And then all of a sudden I heard the baby crying and I yelled to him not to, and that's when I woke up."

She drew a deep breath. "Maybe I really did hear him crying, mother. He—oh, mother!" Arlene's eyes widened. "Mrs. Vandahl will be terribly worried about him when she comes home and finds the house on fire and doesn't know where he is."

"Your father's there, dear." No use upsetting the child more by telling her Lorna Vandahl would never come home again to her baby. "And I want you to go to sleep or you'll never be able to get up in time for school in the morning. It must be terribly late."

She glanced at the little ivory clock on the night table. "It is. It's nearly half past one." And her husband not home yet. "Now, close your eyes and go to sleep at once."

Arlene moved down under the covers. "I will, mother. I'll go to sleep, but please, please go in and make sure Lenny's all right. Please."

"Of course I will. Good-night, darling."

"Good-night, mother."

The spare room was at the back of the house and there was no moonlight in it. Mary Morgan could make out only vaguely, in the bed along which she'd arranged a fence of chair backs so the baby would not roll out, the tiny mound of blankets and the shape of the curly small head.

But she could hear the infant's quiet breathing. Everything was all right.

Poor little orphan, she thought. What will become of it now? She thought of Arlene's saying that she wished they could keep it. Maybe they could. She would talk it over with her husband when he came home.

Why wasn't he home yet?

She went to the window, shivering a little in the cold air that came in through the three-inch opening between its lower sash and the sill. Out there the shadow of the house lay black on the kitchen garden and the chicken run, and reached almost to the barn. Past the barn, however, the moon was bright on the home meadow and she could look across it and see up the road to where it curved behind the woods.

The road was as empty as the sky and there no longer was any red glow of fire in the sky. The deep bong welling up to her from the grandfather clock in the entrance foyer seemed to strike her breast like a leaden mallet.

You're being silly, she told herself. Nothing's happened to John. The thing to do is go downstairs and put up some coffee so he'll have something hot to drink when he gets home, cold and tired.

But she did not turn from the window. Some movement half seen, perhaps some sound half heard, kept her there, staring out.

She saw nothing. She saw only the narrow roof of the back porch, just below. She saw only the kitchen garden under its blanket of mulch, dimly outlined, and as dim in the shadow of the house the bare ground of the mesh-fenced chicken run. There! Near the farther end of the henhouse, against its black wall, a dark blotch.

Maybe it was canvas John had hung from a nail. Maybe it was only a trick of moonlight.

Her eyes widened then. It was moving!

Clumsily. Slowly, as if every inch of movement required a separate effort, was a separate pain, it moved out of the shadow and into the bright moon-glow and halted again. Huge, the color of ashes, grotesquely not quite the shape of a man, it stood on columnar legs watching the house.

Scanning the house for a way in.

THE growling vibration, sensed rather than heard, that had pulled Morgan back to the verge of consciousness faded. Now there was only awareness of pain and of earth smell and the reek of wood burned and wetted down.

And a stench that had no name but was crawling and horrible.

Pain throbbed in his skull. His lids slitted, parted, but darkness pressed against his eyeballs, almost tangible. He could not see but he sensed, as the blind do, the close loom of prisoning walls.

It came to him that he lay sprawled on a flat surface with the harsh feel of carpeting. That was wrong. It should be ground, the leaf-covered ground of the woods. Recollection was back, of the dark woods, of the gaunt apparition that had held his attention while something had sneaked up behind to smash him. Something? The Golem?

"I'm on my way to your house."

They'd been on their way to the house where his wife and daughter slept, the man who'd died tonight and the monster given grisly life centuries ago. "No," Morgan groaned. He thrust down with his hands and somehow was on his feet. He lurched through a dizzy swirl of pain, thudded into a wall. A little further searching brought him to a door frame. His hands felt the door and clawed for its knob.

There was none.

There was nothing his clawing hands could take hold of. The door fitted its frame so tightly he could not even get fingernails into the seam. He groaned, pounded the door with his fists. Then he froze.

"No use, Morgan," a voice was saying behind him. "It can't be opened from within." It was a voice he'd heard only once, and that after its owner was dead, but he'd recognize it in Hell. "And the last of the men have left in their cars, so there's no one to hear you call for help."

Morgan seemed to hear in the phantom's tones an echo of his own despair. "We may feel better if we have some light." He twisted to the click of a switch, but the black dark still thumbed his eyes.

He was blind. The Golem's blow had destroyed his sight.

"Silly of me," he heard out there in the impenetrable dark, "to have forgotten that the fire would have fused the wires." He heard movement in the dark, the scrape of wood on wood, a sigh. "Yes, she did say she'd left this here, that time your local power circuits went out during a storm."

It was light that blinded Morgan now. Blessed light. He could see. Nothing else mattered for the moment.

The source of the light was moving. His pupils accommodated and he saw that the light slid long shadows about a space some eight feet by ten, its walls and low ceiling roughly finished planks of age-darkened wood, closely set. There were the shadows of an oblong table, of chairs solidly built. Directly across from him, against the wall, was a bed—a bunk—whose side- rail was a ponderous beam, its legs sawed from logs a foot in diameter. The light steadied and Morgan saw that it came from a dry-cell lamp which a tall, gaunt shape reached up to hang on a high nail in the wall.

Morgan licked dry lips. He said, "You were supposed to have burned to death in your car."

The phantom was very still. Its hand spread fingers at its side, clenched. "I was not in that car when it burned. The man who died in it beside my wife was the lover for whom she was leaving me."

Martin Vandahl hobbled to a chair, let himself wearily down into it. "They did not get far with all their planning. They sent me to the city by means of a letter that came for me this morning. The first train I could catch after I'd discovered that it was a fake got me back to Montville at eight forty-three. Needless to say, Lorna was not at the station to meet me, but I had no place to go except home.

"Home," he repeated, bitterly. "I set out to walk cross- country, not wanting to talk to anyone, not wanting to meet anyone who knew me. From about a mile away I saw that my house was on fire and by the time I reached it men already were arriving to fight the fire. I joined them, unrecognized in the excitement, and overheard the marshal tell someone about the accident to the car and that you had taken the baby to your home. I decided to go for it and—" He shrugged. "No sense standing, Morgan. Come and sit down."

"Sit down?" Morgan looked around for another door, for a window. "Mary—my wife—will be worried about me. I've got to get out of here."

THERE was no other door. There was no window.

"Out?" Vandahl's chuckle was grim. "How do you expect to, my friend? This is the old icehouse, by the pond at the edge of the woods."

"The icehouse." Morgan knew the structure, unused since electricity had made artificial refrigeration possible. Its walls were solid oak three inches through, their only openings narrow ventilation slits under the earth-piled roof. Its door was dogged shut against animal depredation by an heavy iron lever and lug. "We'd need dynamite to get out of here," he said.

"Precisely." Vandahl's hand clenched on the table, knuckles whitening. "That's why I was so sure it would hold him safe."

"You had a prisoner here." Of course. That was the reason for the furniture. For the bed. Now he knew why the bed was built to support an enormous weight, why the air of this place crawled with a nameless stench. "The Golem."

"The Golem?"

"The stone monster of Frankfort." Morgan pushed away from the door, his voice a deep rumble in his chest. "Don't try to deny it. My daughter saw it in the house just before the fire broke out. She felt its stone hand and it was only by a miracle that she got away from it."

Vandahl seemed almost to have forgotten he was there. "The Golem," he repeated, in the tone of a man who at long last has found the answer to a question that has burdened him too long. "So that's why Lorna would never let me see her brother."

"Her brother!" It was Morgan's turn to snatch at a word, incredulous. "How can that be? The Golem was given life eight centuries ago. It's not human."

"I've sometimes wondered whether she was." The other was aware of him again. "But I do know she is not stone, my friend. Out of the bitter sixteen months of our marriage, I can assure you that she may be fire and ice—she is not by any means stone."

Vandahl's mouth twisted into a smile. "The love that comes to a man at my age, Morgan, is different from that of youth. It is complete, devastating. It is a surrender of thought and will. I met Lorna about two years ago and was lost. It made no difference to me that she evaded my questions as to her background. All I knew was that a faint trace of accent in her perfect English betrayed it as not her native tongue. I did not care that she refused to tell me the source of her evident wealth or why, in spite of it, she had no servants. I even accepted her strange insistence that I always leave her home by midnight or, if we were out, have her at her door by that hour.

"All I cared about was to win her as my wife and, God help me, I did."

Vandahl dropped his face into his hands and in the tense silence Morgan heard his hoarse breathing.

"She could no longer send me away at midnight, but she could, and did, forbid me to enter a certain room, the door of which was always locked. I knew she kept something alive in there for she would go in there and I'd hear her voice behind the door and a mewling that seemed to answer her. One night she opened the door unexpectedly and before she could slam it shut I glimpsed the swollen and horrible thing that was in the room.

"That was when she told me it was her brother. He'd traveled in the Far East, she said, and had contracted there the dread disease called elephantiasis that bloats its victims' bodies to twice their natural size and transforms their skin to the bluish- grey color of the animal that gives it its name. He was half blind, she said, and all but wholly demented, but she could not endure the thought of committing him to an institution. I need not have anything to do with him, in fact must not. He most likely would attack me. She would care for him herself, as she always had.

"I was too damnably much in love with her to object. Until the baby was born. I persuaded her then that to have a madman in the house with the child was the height of folly, but she still would not hear of his being put away. I had to agree to the arrangement we had here. After we found this place I fixed up this icehouse with my own hands, but it was Lorna who brought her brother here at night, alone in the car with him, and I never entered it again.

"That one glimpse of him," the recital ended, "was all I had until tonight when he attacked us. Even then, until what you said just now, I did not realize that my supposed brother-in-law is—not human."

Vandahl sighed. "Obviously, my dear wife released him—it—before she left, in the hope that it would kill me. Instead, with a certain grim humor, it locked me, and you, in here to die of thirst and hunger." The hands fell heavily to the table. "It is too bad that you should be involved. As for myself, I am content to wait here for death."

Morgan leaned forward. "We're not going to die, Vandahl, either of us. When I don't show up in an hour or so, my wife will have the whole township out searching for us, and the Golem's tracks will lead them to us."

"Are you sure, Morgan?" Was he? Did not the legend tell how the stone monster had prowled the Frankfort Ghetto for years and left no spoor by which it could be traced to its laid? "Are you very sure," Vandahl asked, "that in an hour or so your wife will know whether you've come home or not? Or care?"

Morgan's voice trembled. "What are you driving at?"

Vandahl shrugged. "Hasn't it occurred to you," he asked, "that, as I did, the Golem could also have learned where the baby is? Do you think he'll let a lone woman keep him from it?"

MARY MORGAN did not quite know how she'd gotten

down here to the phone on the wall beside the grandfather

clock. She was aware only that she'd come quietly so as not

to awaken Arlene to new terror, that she must speak quietly

now so Arlene would not hear her tell the operator to send

help.

She palmed the bells with her left hand, muffling their tinkle as she ground the ringing handle with her right. She took the receiver off the hook and put it to her ear.

The hard rubber was cold against her ear. Cold—and dead.

She knew now what the prowler had been doing at the corner of the henhouse where she'd first glimpsed him. The phone wires ran there before they angled off across the fields, and the insulators to which they were fastened were well within reach of a tall man.

Mary hung the useless receiver back on its hook gently. Her hand still on it, she made herself think, made herself decide what she must do.

She remembered gratefully that the kitchen door was locked. She'd reminded Morgan to do that when he'd come in from his chores He'd gone the rounds of the downstairs windows, too, locking them before he'd settled down to his paper, but he'd left the front door spring lock unlatched till Arlene should return.

The first thing to do, then, was to see to that.

Moving to it seemed like wading through some invisible fluid that somehow had flooded the foyer, knee high, but she got to the door and opened it and thumbed the latch button in its edge. As she started to close it she heard a faint sound in the night, held it, listening tautly.

Was it the vibration of an approaching motor? Let it be, Mary prayed voicelessly. Please God, let it be John coming home.

If it was, she must warn him the instant he got in the driveway. She moved her hand to the outer doorknob, stepped out on the porch, listened again. Did she hear that car? She wasn't sure. She leaned far out to look up the road, leaned a little too far. The door clicked shut.

And the road was starkly empty, the car sound gone.

Mary whirled, thrust at the door in panic. No use. It was locked. She was locked out of the house, locked out from Arlene and the baby, locked out into the night where that grey and terrible thing prowled.

She dared not call to her daughter to let her in. The prowler would hear, would come running, might arrive just as Arlene was opening the door for her.

This way the child was safe, for a while at least. That she should be so was more important than that Mary herself was out in the open, in danger, and with no weapon except her bare hands.

Wait. There was a weapon she might be able to get at. John's scythe, hanging on the wall, just inside the barn door. Perhaps, if she stole very quietly through the shadows, she might reach it without being seen.

Mary went to the end of the porch, climbed over the rail. She slipped along the side wall of the house towards the back, the lawn's dried grass whispering loudly under her feet. She was almost to the corner when she heard wood creak, around in back, as if under a heavy weight, and then a rasp of stone on wood and a sudden, metallic clank.

Something had struck the tin bucket in which she mixed chicken feed. It hung high up on a support of the back porch roof. She knew now what the sound meant. The prowler was climbing to the porch roof, and from there he could reach windows that were not locked. He'd be inside the house before she could possibly get the scythe and get back.

If she were to stop him at all it must be now, unarmed.

Mary went around the corner of the house, fast, and saw the grey and monstrous figure that was poised on the porch rail, groping at the roof edge for a hold. "Down," she gasped. "Get down out of there," and the round head rolled, peered blindly down at her. A stench as of something long dead and rotted was in her nostrils as she got both hands on one of the huge legs and pulled at it.

It was like pulling at a statue's stone leg, but no statue would make the mewling, meaningless sounds she heard above her. She planted her feet against the bottom of the porch, threw herself backward and put her strength into one desperate effort. The foot rasped off the rail then, and the grey body toppled, was hurtling down atop her as she fell.

It seemed to Mary Morgan that she heard a howl of unutterable anguish as the monster fell down on her.

JOHN MORGAN took hold of the top of a chair, so

tightly the blood seemed about to burst from his flattened

fingertips. "There's got to be some way to get out of

here." He looked around the interior of the icehouse, but

there was no indication that the walls had been touched

since they'd been built by old Jethro Foster seventy years

ago. "Good Lord, man," he groaned to Vandahl. "How can you

sit there so calmly? My wife and daughter may be in that

house, but it's the baby the Golem is after. Your son."

"Not my son, Morgan. Lorna's, but not mine. She thought I believed it was mine but I knew it was not."

That was when Morgan spied the cord dangling from the light fixture in the ceiling. "You installed that light?"

"Of course."

"And you're no electrician." He stepped on a chair seat, then up on the tabletop as he dug his jackknife out of his trouser pocket. "You're not even farmer enough to handle tools properly."

He thumb-nailed the screwdriver blade open, reached up to use it on one of the three screws that fastened the socket plate in place. "The way the board here is splintered, I'll bet you used an axe to chop a hole through the roof for the wires."

"Right." Vandahl was out of his own chair, gaping up at him. "But it isn't big enough for an infant to crawl through."

"I'll make it big enough."

The first screw was out. Morgan tackled a second, then the third. It dropped and the plate dropped with it to dangle on stiffly coiled black wires. He changed blades and hacked through the wires, saw that the jaggedly edged hole the plate had covered was only some ten inches across at its widest.

The assembly dropped. The bulb exploded at his feet but Morgan was working on the wider rim with his knife. He cut a V to the plank's edge in a minute or two, whittled through the other rim in less time and, without pause, bent, lifted the chair he'd used as a step and thrust a leg slantingly into the aperture, parallel to the plank's length, as far as the rung would let him.

He hung his whole weight on that chair leg, levering downward.

The old wood creaked, sagged a little, but held. Then Vandahl was up beside him, grasping the chair leg, adding his weight. Wood cracked and the plank angled downward so suddenly that as the leg slid out Vandahl staggered against Morgan and jolted him from the table.

He fell sprawling, rolled, pushed up and was knocked down again by the table itself skidding against him while he was still off balance. "You clumsy ass," he grunted at the legs that vanished through the hole in the ceiling. He shoved the table back under and clambered up on it again.

The hole's splintered edge cut into his palms, gripped his shoulders. Then he was through and from the roof saw the moonlight bright on the pond's icy surface, heard a threshing of underbrush in the dark woods that told him Vandahl had a long head start on him.

Morgan leaped down and fought through the thick brush to the path that led toward his car. Sickening fear made him run even faster. How long had he been unconscious? What had happened—what was happening—to Mary? To Arlene?

ARLENE was sure she must be dreaming again. The Wakeful Foe had howled like something hurt it terribly and now she heard Lenny crying.

She wasn't dreaming. Her eyes were open on the moonlit dimness of her own room but she could still hear the baby crying as if it had been awakened by some noise and was frightened. Arlene threw off the covers and swung her feet to the floor. The cold struck through her and she shivered, but she got up and padded across the hall, her bare toes curling from the cold of the floor.

It was dark in the spare room, but she could tell where the baby was by the sound of his crying. "Yes, Lenny," she crooned. "Don't cry. Arlene's here." She bumped into one of the chairs her mother had put along the bed but the baby's crying was stopping. Arlene fumbled at the chair and pulled it out so she could reach him. The scraping on the floor didn't stop when she stopped pulling the chair.

The scraping wasn't here. Arlene turned to where it came from, to the pale oblong of the window at the end of the room.

Then she was back in the lonely terror of her dream. She must be back in her dream because in the frame of the window, black and terrible, was the lumped shape of the Wakeful Foe and the window was scraping open to let it in.

It had heard Lenny crying and so knew where the baby was. Now it was coming in to get him.

MORGAN seemed to have been running forever through

the nightmare woods, the leaves rustling under his feet,

exhaustion racking his limbs, but now at last the woods

were brightening and he stumbled out of them into the

stubbled field at whose edge he'd left his car.

It took him a moment before he spied his car, and then he started with shock. The car was moving! It was making a tight U- turn in the road. It straightened out and Morgan saw who was at the wheel. Vandahl! Following the path, Vandahl had come out here and spied the car, and he was turning it in the right direction for a quick getaway when Morgan arrived.

But it didn't stop. It gathered speed, was roaring away—without Morgan.

"Wait!" Morgan shouted. "Wait for me, you fool!" Calling on his last ounce of strength, he sprinted across the field. "Wait!" But there was no use shouting. The sedan was gone.

Morgan reeled out into the road and started to walk toward his home. His heart was pounding. His legs were like rubber. He'd never be able to make it.

Then the car sound that had faded was loudening again. Vandahl must have heard his shout at the last moment, turned and was coming back for him.

ARLENE knew now that she was not dreaming. The Foe had

lurched in through the window and stood now just inside

it. She could smell it, and she knew that you can't smell

anything in a dream.

It was a horrible smell. The Foe was horrible, all big and grey and clumsy shaped as it stood peering into the room as if it were trying to see what was in here but couldn't. Maybe it was blind. Maybe if she kept very still it would think the room was empty and go away.

The baby whimpered.

The Foe's hideous head turned to where the whimper came from, so maybe it didn't hear the other sound Arlene heard, the sound of a car coming along the road. Of Dad's car. She knew the sound of it almost as well as she knew Dad's voice. The foot thudded on the floor, and then the other foot, and it was lumbering toward the bed. Arlene couldn't hear Dad's car any more. Maybe it had reached the house and stopped. The Foe bumped into a chair and its huge arm swung, stiff and straight like a club, and knocked the chair across the floor.

"Dad!" Arlene screamed. "Help!"

The Foe swung to her and her throat locked on the scream. The baby was crying again and she heard a muffled shout, down below, and the sound of breaking glass. The Foe was mewling at her, like a cat trying to say something. Somehow that unlocked Arlene's throat again and she said, "Don't touch Lenny. Don't hurt the baby. I won't let you."

The Foe turned back to the bed and stooped, its big grey arms reaching down for Lenny, but Arlene bent more quickly. She pulled the baby up, twisted to run—and was tripped by the chair the Foe had thrown down.

"Dad!" she yelled as she fell. "Dad!" And a distant shout answered, "Where are you?"

Arlene was all tangled in the chair and the baby was crying and the Foe was moving toward her, but she yelled back, "Here! Upstairs in the spare room!" and as she yelled she knew it wasn't her father who'd shouted.

"Coming," the stranger yelled, nearer, his footfalls on the stairs. The Foe mewled and lurched out of the room and Arlene heard it clumping in the hall. Then she heard a shout and feet running past the door. The noises of a fierce fight exploded out there, shufflings and grunts, and the sound of blows.

Arlene was shaking violently, but she pushed the chair away and sat up, gathering the baby into her arms. "Hush," she crooned. "Hush," as she listened to the noise of fighting get farther away. "Please stop crying."

The baby snuggled against her and his crying grew quieter, and now he was only sobbing. Arlene got up and started to go to the window to climb out, but when she reached the window she knew she couldn't climb out with the baby in her arms, and of course she couldn't leave him.

Then the noise of fighting in the hall stopped.

She turned back to the door, stood listening. She heard someone coming along the hall slowly! As if he were very tired. As if he'd been hurt in the fight but was trying to get to her.

Which one was it?

THE car John Morgan had heard skidded to a

squealing halt beside him, but it was not his sedan and it

had come from behind him. It was a battered old coupé and

the man who leaned across from its steering wheel and threw

open its door was Marshall Cal Hutson.

"John!" he exclaimed. "What in thunder are you doin' out here, lookin' like you been in a tussle with Satan himself?"

"That's about what I have been." Morgan got hold of the car door and hauled himself in. "Get me home, Cal. Fast." He dropped heavily into the seat "Hurry, Cal." The car was in motion again, but slowly. "Oh, Lord, can't you go faster than this?"

"Yeah," the peace officer grunted, "but I ain't goin' to. I been pokin' 'round the ruins of the Foster house. I found out something. That fire was set, John. What I want to know is why your daughter didn't phone the alarm before it got a good hold on the old wood."

"She wasn't in the house." No time now to explain the incredible thing she'd seen. "She saw the firebug setting it and ran out, carrying the baby. He knows she saw him and is after her to silence her, and if you don't speed up, Cal, we may be too late to save her."

"Right." The coupé fairly leaped into racketing flight. "What got me suspicious of that fire," Hutson shouted above it, "was what we turned up when the Vandahl car cooled off." They were rounding the curve where the fence began. "In what was left of the gas tank. The remains of some clockwork that looked like it might of been part of a fire bomb."

Now the car surged into the driveway and was stopping next to Morgan's own car. There was a dark shadow before the front house door and Morgan's heart sank.

He hit the ground before the coupé had quite stopped, half stumbled, half fell up the porch steps and had his arm around the limp figure whose bruised mouth mumbled his name. "John. You... I heard your car crawled around here... but door locked. Is—is Arlene all right?"

"I don't know. Where is she, Mary?"

"Inside. I heard her scream...."

"And the door's locked, you say? I—"

"Window open there." That was Hutson, behind him, pointing to a gaping parlor window and now starting for it. Morgan lifted his wife in his arms, got to the window seemingly in the same motion. His heels crunched on broken glass as he stepped through, saw Cal already in the doorway to the foyer. He put Mary down in a big chair, said, "Stay there!" and ran after Hutson. Remembering the switch in the foyer wall that turned on the upstairs hall light, he jabbed it as he passed, not stopping.

The marshal was stark against sudden light at the upper stair- head as Morgan started up. He had halted, staring down the hall as though he saw something that appalled him, then pounded away. Morgan reached the top, saw what it was that Cal was running toward far down the hall, but as he turned the newel post to follow he heard a wordless, sobbing cry from within a door Hutson had passed.

"Arlene!" burst from his tortured lungs. He reached for the door, grabbed the frame and swung himself into the spare room.

He stopped short, staring past the shambles of overturned chairs at Arlene, her back to the window, the baby tightly clasped to her breast as she defiantly confronted a tall, disheveled figure.

"I'm not going to hurt you, little girl," Martin Vandahl was saying. "I've no intention of harming you or the baby." And whirled, swinging up a monkey wrench to hurl it at Morgan.

The wrench halted in midair and Vandahl stared. "Morgan." His hand dropped. "God, man, I thought you were—" Surprise was in his bruised and bloody face. "I didn't hear you coming."

"Didn't you?" Morgan asked dully, but Arlene pushed past Vandahl and rushed to him with a cry heartrending in its glad relief. He knelt to receive her, had her sobbing, shuddering small form folded to him, careless of the baby. "All right, darling," he murmured. "It's all right, honey. Everything's all right."

"He was going to hit us," she sobbed. "I don't care what he says—he was going to hit us."

"You heard him say he wasn't, dear," Morgan said, his voice steadying. "We ought to believe him." He held his daughter close and her sobs quieted, but the baby was beginning to whimper. "Tell you what you do, Arlene. You take Lenny in your own room and put him on your bed. Then put a bathrobe on and slippers, and take a blanket down to your mother in the parlor."

"All right, Daddy."

She was gone and Vandahl was saying as Morgan rose, "She's a brave little tyke." And then, "Good thing I didn't wait for you. I got here just in the nick of time to save her."

"So I see." Morgan stepped to him, took the wrench from his hand. "This is from my car, I think. Apparently it was a good enough weapon for you to kill the—the Golem with. I thought it was immortal."

VANDAHL pulled the back of his hand across

his brow. "We were wrong about that, Morgan. He's

not—"

He broke off as Hutson's voice came in from the hall: "What is it, John? What in the name of all that's holy is that creature layin' dead out there?"

Hutson lurched in through the door, stopped short, his eyes bulging. "Hey!" he cried, staring at the white-haired man. "You're Martin Vandahl! Weren't you burned up in your car?"

"Obviously not," Morgan answered for him. "He's Vandahl in person, not a ghost, and that creature out there is his brother- in-law. But this man, Cal, is your firebug." He stepped closer, the wrench lifting. "Your arsonist and murderer."

Vandahl laughed. He said to Hutson, "I don't wonder the man's mind has broken with all he's gone through tonight."

"My mind's quite all right," Morgan said. "Now. It must have been near to breaking back there in the icehouse or I'd have known then that you were lying. You never went to the city, my friend. You told your wife you had because you'd planted an incendiary machine in the gas tank of her car, timed to go off when she drove to the station to meet you on the eight forty- two.

"That wasn't the act of a Golem, nor that of a madman who was kept locked up and could have gotten neither the materials to make that bomb nor the opportunity to plant it."

Hutson tried to break in, but Morgan said, "Wait, Cal," and went on, relentlessly. "Some hitch-hiker your wife had picked up, Vandahl, died with her, but the baby escaped. You found that out when, returning to your home, you saw my daughter in the lighted parlor.

"What you did then was get into the house, probably through a basement window, and set fire to it. And then you released your brother-in-law so that he'd be blamed for both murders, as you'd planned that he'd be blamed for the first if it were discovered not to have been an accident. That was a mistake. He saw the flicker of flames in the cellar, broke into the house to warn his sister and frightened Arlene into running out with the infant."

"Hold it, John," Hutson broke in. "The brother-in-law did come here after them, didn't he?"

"Sure he did. He figured Vandahl would make another attempt at the child and set out to forestall him. He got lost in the woods, found the path just as I blundered on this man, knocked us both out and resumed his painful journey to this house.

"In the meantime Vandahl was stuffing me with the yarn he'd concocted to cover himself, but when I found a way to escape from our prison he contrived to get out ahead of me and beat me to my car. He reached here in time to kill his brother-in-law, and if he hadn't heard my shout would have killed the baby. And Arlene. With her silenced, it would have appeared that he'd gotten here just too late to save them.

"That's that," he sighed. "That's the story."

"And a very pretty one," Vandahl grinned. "Except, Morgan, that you've failed to give a motive for going to such great lengths to kill my wife and child."

"Not your child, as you told me. Remember? That might almost be motive enough, but you also told me that Lorna was wealthy. With her and the child dead, as well as her brother, you're the sole heir to her fortune." Morgan turned to the marshal. "Satisfied, Cal?"

"Well." Hutson rubbed his jaw. "I dunno. If he can prove he was in the city an' only got back on the eight forty-two he wouldn't of had time to reach the house by the time the fire broke out. It was fifty minutes late tonight."

"He wasn't in the city. That was what I meant when I said I should have known he was lying back in the icehouse. You see, Cal, he told me his wife had a letter sent him that lured him there, but I happen to know the only letter that's come to his house since they've lived here was addressed not to Martin but to Lorna Vandahl. I—"

"Daddy!" Arlene's voice. "The Wakeful Foe's outside. I just looked out the window and saw him going in the woods."

Morgan went to her, saying, "No dear. You saw some mist or something. He's down there at the end—" He broke off. At the end of the hall, where he'd seen a blue-grey mound on the floor, was only the blank wall that ended it.

Hutson thrust past him, dragging his prisoner. He stopped short, jaw dropping.

"I don't believe it," he groaned. "He couldn't of been just stunned. There was a big hunk busted out of his head."

Morgan gasped and moved down the hall, the others behind him. He stooped, came up with the thing he'd seen, a chunk of blue- grey stone as big as his fist, one surface rounded, smooth, the others jagged. Freshly fractured. He thrust it at Hutson. "Is this," he demanded, "like the pieces you found where the car burned?"

Hutson's mouth opened. Closed. Opened again. "Yeah," he got out. "Just like—Why?"

"It doesn't come from any quarry around here. I'd have to check—it's years since I studied geology at college—but unless I'm mistaken, this is a special type of granite found only in Central Europe."

"In Germany," Vandahl made the point clearer. "Near Frankfort. Now will you believe that Lorna was not what she seemed?" But it was at Arlene that Morgan was looking.

"Arlene," he asked. "Why have you been calling the—it—the Wakeful Foe?"

"On account of what Mrs. Vandahl said when she went out, Daddy. She told me to intermit no watch and then I saw it in the book on the desk: 'Intermit no watch against a wakeful Foe.'"

"'While I abroad;'" John Morgan finished the quotation, "'through all the coasts of dark destruction seek deliverance for us all.'" He turned to Hutson, a chill prickle traveling his spine. "That's from Milton's Paradise Lost, Cal. Do you know who speaks those lines in the poem?"

"How would I know, John? Who does?"

"Satan," Morgan told him, "to his fallen angels just after they have been evicted from Heaven. And the Wakeful Foe, Cal—the Wakeful Foe he means is the messenger of the Almighty Himself."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.