RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vintage German poster

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vintage German poster

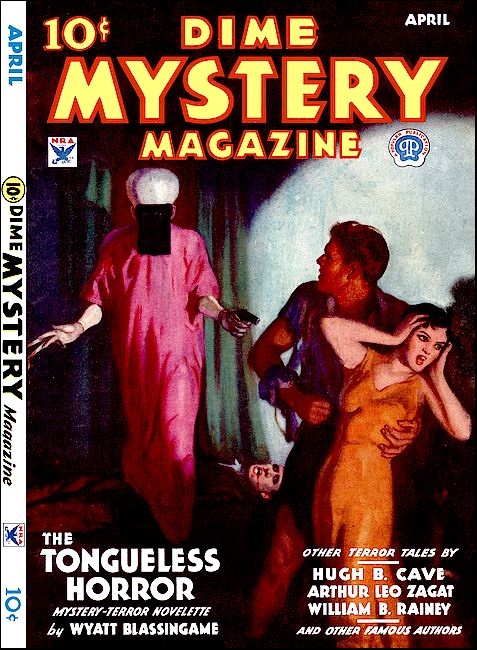

Dime Mystery Magazine, April 1934, with "Death Dancers"

Their clothes were winding sheets, their weapon madness—when, in the

full of the moon, they held their obscene carnival of doom on Dark Mountain!

WHEN I saw that strange clearing for the first time, plunging out from behind the screening evergreens, the hairs at the back of my neck prickled and I was chilled by a sudden inward cold. Perhaps it was the oddly ominous shadow as the sun dropped below Dark Mountain's looming peak; perhaps the way our dog, Joseph, with the coat of many colors, growled and cringed against my feet, communicated to me a feeling of something horribly wrong about the place. Perhaps it was neither of these but an adumbration of the horrors that had been and were to be enacted here that I sensed impalpably tainting the tree-hemmed circle. Whatever it was, I was not the only one to feel it. Art Shane, and Jimmy Carle, our chainman, stood rigid as I, staring through slitted eyes and breathing a bit hard.

"What do you make of it Dan?" Art asked finally, his lusty bellow hushed for once.

"Queer!" My slow monosyllable was almost whispered, though as far as I knew we were the only humans within a score of miles. "Damn queer!"

For three days, pushing our railroad survey through the untenanted Wiscarado State Forest, we had seen nothing but trees, great towering pines that dwarfed us into three insignificant, crawling worms. And now, at the end of the third day's final traverse, we had come upon this open space, flat as a table, a rent in the mountain's arboreal garment some hundred feet across. Absolutely circular, as if its boundaries had been scribed with gigantic compasses, it was obviously man-formed. Natural causes could never have attained such regularity. Nor had the clearing been recently made; its floor except at the center, was covered with too heavy a growth of grass and vines for that.

Except at the mathematical center! There a thirty foot ring was absolutely bare, the earth showing, clean! Within that, the hub of the whole formation, was a single huge boulder, gray-green and lichen-covered, a squat, flat-topped cylinder immemorially aged. This also was obviously not the work of nature, neither in shape nor position. Humans had formed it and brought it here, years ago.

It put a man furiously to think. How, for instance, had they hauled that giant stone up here? And why? Why had that central ring not been overgrown, long ago?

I shuddered, then reddened. Swell chief of a survey party I was making, getting the jitters over finding an unexpected clearing with an old stone stuck in the middle of it! I could imagine what dad or John Hepburn would have said could they have seen me. The old Tiger, with the first Dan Hale at his elbow, clawed his way across half a continent, fighting savage nature on the one hand and the no less savage Wolf Hopper and his gangs of Estey roughnecks on the other. And here I was getting cold shivers up my yellow spine over the first thing that popped up that was not cut and dried! I clenched my fists and swore under my breath.

"Come on," I said. "I'm going to look that rock over."

I started across to it, and the others followed. I got a glimpse of eighteen-year-old Jimmy's face. His lower lip was caught under his teeth and too much white showed in his eyes. He'd been nervous as hell all day, peering around tree trunks for things that weren't there. A weak sister, all right. Too bad. He was a likable kid except for the streak in him.

Maybe he wouldn't have shown up quite so badly if it weren't for the contrast with Shane. My assistant was out of the Western Division and I'd known him less than a week, but there was a set to his jaw that I liked, and a competent swing to his big shoulders. He had a grin, too, that got under my skin ....

"Look at this, Dan." Art nodded at an oval depression in the rock's upper surface. "I'd say it was water-worn, but there's nothing to keep any weathering from affecting the whole top."

I am well over six feet, but the boulder rose chin-high to me and its diameter doubled its height. The shallow, bowl-like depression touched the edge at one point and from there a weathered groove ran straight down the stone's side. Where it reached the ground the earth was darkened, stained as if some dark fluid had soaked into it. I bent to examine the blotch more closely.

"Dan!" Jimmy squealed. "Art! What's Joseph got? What's the dog doing? Look!"

I jerked up, followed the kid's pointing finger. The dog was across the clearing, digging furiously. He was barking short, excited barks; and even from where I stood I could see that the hair on his neck was bristling like a ruff.

I was fed up with the carrot-topped youngster's jumpiness, with my own too.

"Go ahead and find out what he's doing if you want to," I growled.

They started away and I stopped again to get some of the stained dirt between my fingers. It was stickily granular. I looked at the mark it made on my skin. It was reddish-brown, grainy. It was dried blood!

Jimmy screamed, chokingly. There was horror in Shane's shout! "Dan! Come here! Dan!" I whirled and hurtled across to them.

Joey was gnawing at something, growling. I got him by the scruff of the neck and pulled him away.

The thing at which he was gnawing—protruding whitely from the disturbed earth—was a human hand!

WE GOT Joey tied to a tree, got the trench-spade from Jim's

pack, and finished the job the dog had started. I felt sick long

before we were through, and there wasn't much to choose between

the fish-belly white of the kid's face and Shane's green mug. The

man—there was enough left of him to tell he had been

that—had been dead four or five weeks at least. His hair

was very long and black, but his beard was shot with gray. There

was no sign of any clothing having been buried with him.

His head lolled over, sidewise. It was I who uncovered it, and unthinkingly I reached to straighten it. The feel of his bloated flesh—God! I rubbed my fingers against my trouser leg, shuddering, saw the reason for the unnatural position of his skull. His throat had been slashed—sliced clear through to the backbone!

"What's that in his mouth?" I think it was Art who asked. "What is it?"

I forced myself to look closer. There was a thorny flower-stem stuck between the yellow teeth, and what hadn't moldered of the flower looked as if it had been a rose. Not a tiny wildflower, but a full-blown, cultivated rose!

"Where the hell did that come from!" I blurted.

"Never grew in the woods. Must have come from Pinehurst."

"But that's twenty-five miles from here, down the mountain. And I doubt whether anybody grows roses in that godforsaken hamlet."

Shane shrugged. "More important to know how the corpse got here. He didn't take that slice out of his own windpipe."

"No, and he didn't bury himself either. It's murder, Art, murder!"

We stared at each other. A chill ran through me.

Then I pulled myself together. "Whoever did it is a long ways away from here by now," I said. "We'll report this at the first town we get to."

"But..."

"But nothing. Our job is to get this exploration done. We're a railway survey party, not a posse of detectives. Lord knows we've got our work cut out to get through and get a report in before the time-limit. We'll cover this up, make camp, and be ready for work at sun-up."

"Camp?" Carle's voice was a croak. "Where?"

"Right here in this clearing. It's the best camp-site we've found since we started from Pinehurst."

"B-but this—" Jimmy squeezed out through white lips. "Th-this...."

"Great Jumping Jehosaphat!" I bellowed. "The stiff isn't going to bother us any—not if we keep to leeward of it." My skin was still crawling with goose-pimples, but I wasn't going to let him know that. "The killer is hundreds of miles from here by now."

The kid's eyes were dark pools in the glimmering paleness of his face. "I can't, Mr. Hale—I can't sleep with this around—" He was staring at the grave. "I know I won't live through the night if I do!"

I grabbed his shoulder, whirled him around to me. "Look here, Carle!" I snapped. "You'll sleep when and where I tell you to, and do as I tell you, or you're through. For good. Quit on me now and I'll have you blacklisted on every road from Canada to Mexico!"

Shane put a hand on my arm. "Hey, Dan," he admonished. "Don't be so rough on the kid." A slow grin creased his big-boned face. "Remember you were a cub once yourself."

I shoved him aside. "Keep out of this, Shane," I grunted. "I'm in charge of this outfit and by God, I'm going to run it!"

Jimmy blinked, and his face was so woe-begone that I almost chortled in spite of my anger. But Art saluted; said, in a meek, piping voice, "Yes, sir," and bent to pick up the spade. "Come on, Jimmy," he added. "We'll shovel the dirt back while the boss picks out a spot." As I turned away I could just hear him whistling between his teeth, "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?"

That made me realize what an ass I was, blowing about my own importance. Anyone could guess that this was my first big job in the field after being tied to a desk for more chafing years than I care to think about. I skirted the clearing edge and recalled what dad used to say about Hepburn, before dad passed on:

"The Tiger never raised his voice to one of us until he was ready to kick him out of camp. And then he was a holy terror. He'd stand there, pulling at the lobe of his ear with his big mitt and roaring like the big cat he was named after, and the chap he was bawling out felt just about big enough to crawl under a snake's belly. Glory be, when old John jerked his ear like that he sure pulled the latch-string to hell. If you make half the man he was, Danny boy, I'll smile in my grave."

To my left the mysterious rock seemed to loom a living, ominous presence, quiescent only for the moment. A strange hush lay over everything. I had a queer sense that some alien presence was watching me from the darkness of the trees. My hands shook a little as I knelt to start a fire.

NONE of us talked much, after our meal of canned willie and baked potatoes was finished. The dog had chewed through his leash, and we'd had a devil of a time keeping him from again exhuming the murdered corpse. He was lashed tightly to a nearby sapling now, his muzzle bandaged to quiet his infernal growling. That incident had put the final damper on our spirits. We sat hunched moodily around the fire, each busy with his own thoughts. After a while I glanced at my wrist watch.

"Seven-thirty, fellows," I said. "Turn in. We start at sun-up."

Jimmy looked at me with lack-luster eyes. "I'll sit up and watch, Mr. Hale," he offered. "I can't sleep."

I jumped to my feet, loomed over him. "You'll sleep, young fellow!" I snapped. "If you aren't snoozing in thirty seconds I'll put you to sleep—with this." I pushed my fist against his eyes. "Understand?"

The lad looked up at me, his mouth working, not making a sound. I've never seen a face so miserable. Damn it, would I have to make good my threat?

"Take this pill, Jim," Art said smoothly. "That'll help you."

"No! I won't take any dope. I won't." His voice was edged with hysteria.

"It isn't dope, old man. Just bromides, to quiet your nerves. Swell to sober up on; that's what I carry them for."

The boy looked at my assistant like an adoring pup. "You—you're not kidding me?"

"May I be struck dead," Shane grinned. "Take it, bub."

"Thanks." He washed the white disk down with a swig from his canteen. Then he crawled into his blankets, and closed his eyes. In seconds he was breathing quietly.

Shane motioned me to the other side of the fire. "What say, Dan," he murmured. "Think we ought to set a watch?"

I could afford to be honest with him; there was no question about his guts. "We better had," I agreed. "I don't like the looks of things. Fellow that did for that corpse may still be prowling around. I'll take the first watch, wake you up at one."

"Oke. Watch the fire—it's getting chilly."

I made myself comfortable with my back against a tree. Somehow the firelight seemed not to penetrate far into the close-pressing dark. The big stone was just a darker bulk against the black wall of the pines. I felt stifled. That feeling of being watched was upon me again. A half-dozen times I jumped at the crackle of a twig in the woods, the rustle of the breeze in the looming needles.

But after a while I yawned. The heat of the fire, the somnolent rustle of the pines, were getting me. I propped my lids open. So far things looked swell. It would take doing, but the route over Dark Mountain looked feasible. The L.T. & C. would yet be able to build the cut-off that would beat the Estey to tidewater by ten hours. Tomorrow would tell the story. Tomorrow—we'd start early—and....

A SOUND pulled me out of sleep—a welling sound. Vast

somehow as the mountain itself, yet so far down the scale of

hearing that I felt rather than heard it, felt it as a tremendous

vibration impacting my cramped body. I was on my feet before it

died away, peering into the darkness. The fire was low. Nothing

seemed to stir, not even the blanketed forms of my sleeping

companions. The sound was gone—if there had been a sound. I

tried to convince myself I had dreamed it.

But I couldn't shake off the unreasoning dread that oppressed me, the vague sense of impending catastrophe. For some reason I connected it with the monolith in the clearing's center—forced my gaze to the stone. And saw that, exactly at the point where its edge was nicked by the descending groove, a tiny light glowed, silvery-blue and unearthly!

My scalp tightened for one horrible instant. Blood hammered in my temples. Then the explanation came to me and I laughed, shortly. The mountainside we were on faced east. The moon must have risen, far down on the forest-hidden horizon, must be slanting its rays up along the tree-tops. And one thin beam, sifting through by some trick of foliage, was just touching the boulder's edge.

Hell of a watch I was keeping, falling asleep! Not much but embers was left of the fire. I got a chunk from the pile we had gathered, walked rather unsteadily to the flickering mound and placed the new fuel where the blue flames still licked feebly. The resinous wood caught—flared—threw light along the ground. And I froze.

It couldn't be there—what I thought I saw on the side away from the sleeping men. Against all reason that it should be there—a single rose, erect on its short stem, nodding gently. Red as a gout of blood! I rubbed my eyes—looked again. It bobbed gently in the faint breeze.

There had been a rose in the mouth of the bloated cadaver—a rose where no rose could possibly be. And here was another! A blob of red in the flickering, eerie light—sinister....

How had it gotten there? Who had stuck it there in the earth—what prowler moving silently from out of the forest gloom?

"Roses in the moonlight..." A phrase from some forgotten poem threaded through my numbed brain. They had brought death to—someone. Was this rose too a mocking prophesy of death?

Long waves of cold swelled up through me—chills of abysmal fear. I stared at the thing with widened eyes—saw that a square of white was impaled on one long thorn....

After an eternity I found strength to move, to bend and slip that paper off. There were words on it, crudely printed words that are still burned into my brain:

STRANGER, YOUR WAY IS BARRED!

GO BACK OR TREAD THE DANCE OF DOOM!

FIRELIGHT flickered across the paper and made the words dance. Dance! The Dance of Doom! What was this threat—what did it portend? What was the Dance of Doom?

Suddenly then, while staring at the paper, a new tenseness struck at me—a new fear. There was no sound, no flicker of movement. But I knew there were eyes upon me—eyes from somewhere in the blackness—watching me. My corded neck ached with the slow effort to raise my head, to turn it, slowly, in a long, fearful scanning of the clearing's edge. My straining eyes came slowly around to the point in that dark arc where I knew the grave of the murdered man to be.

And there—at that very spot—a vague, pale form glimmered against the forest gloom. Was it moonlight, the dim, cold luminance by which I saw it, or did it glow with its own spectral light? The phosphorescence of rot, of sepulchral decay?

It was motionless—and I unmoving—while supernatural terror rocked the very foundations of my reason. And then, after an eternity, it moved—backward or forward I could not tell—but it did move—and vanish.

Something—some awful clamor of my soul for assurance that this thing was real and not an emanation from the desecrated grave—flung me into action. My feet drummed across the clearing—hurled me past the looming monolith and on toward the point where the apparition had been.

And with movement came thought. It was someone alive—human. It must be! The killer—the killer, of course! It was the killer and I was not armed. Yet I prayed it might be he. Otherwise... My left foot thudded into soft earth—the grave. The forest was just ahead. I wrenched to a stop, listened.

There was sound, deep in the trees—underbrush crackling—a footfall. Ghosts do not make sounds in the forest! I plunged after—into moonlight spattered gloom—into a weird maze of gigantic black trunks—fuzzy bushes—soft slippery carpeting of fallen needles. I caught a glimpse of a flitting white form, twisted to it, skidded, and caromed off a rough bole.

There was my quarry—gliding through the thicket that hindered me, that snatched at me with its brambles, lashed me with its low-hung branches. It glided so effortlessly, and I forced passage so painfully—yet somehow I never lost sight of it—never lost hope. Always it was just ahead—just to the left or right. When I stumbled, when I fell and heaved myself up with the gasping thought that now—now surely—it would be gone, I saw it instantly. But always beyond my reach. Always just beyond my reach.

A strange, uncanny, voiceless flight and pursuit that was, through the immemorial forest, through the light-splotched darkness. The first madness of the chase went from me, reason functioned, and even as I darted, plunged, through the tearing briary bush I knew fear again.

For it was plain, plain as the rod-line in a transit eye-piece, that I was trapped—lured and trapped. This form I pursued, this killer who thrust roses in the mouths of his victims, was baiting me, drawing me on and on into the forest, far from my companions, far from any who could answer my call for help. He could lose me at any moment—lose me and then swoop on me from behind some bush, some dark covert, slash my throat, and thrust his infernal rose between my teeth. Leave me there to rot, with the rose of death between my lips.

That was his plan, and I knew it, now. Yet I ran on after him—ran on and on—while the fingers of terror plucked at me from the darkness and dread pounded in my breast. I must keep him in sight, must keep his flitting, white, incredible form in front of me. For as long as I saw him I was still safe—but only as long as I saw him....

HOW long would this simulated flight, this hopeless,

fear-laden pursuit, continue? How long could it continue?

My feet were ton-weights at the ends of my weary legs, knives

twisted in my heaving breast, my face was criss-crossed with

deep, bleeding scratches. Only terror—terror of that moment

when I should see him no longer, when he should spring aside,

vanish, launch and leap on my unsuspecting back, his blade

whetted for slaughter—only that terror spurred me on. Even

that—in minutes—would not be enough.

And then it happened. A widening of the moonlight in a wind-rift—a fallen tree trunk.... He tripped on an outflung, dead branch. I left my feet in a frantic dive, got hands on his robe—jerked him down as he strove to rise—heaved and got my body over him, pressing him down. I raised my fist to smash him—and did not strike!

For it was a woman's face that stared into mine—panic-twisted! Long brown hair tumbled down, twined around my stiffened arm that held her! And the warmth of a woman's body struck through to mine that pinned her down!

I heaved upright, not loosing my grip on her arm, dragged her up with me. Blue light slanted down into the wind-riven opening, shimmered over the lithe, full-curved figure to which the white robe clung, half-revealing, painted her face with its soft luminance. The face was young in its hazy frame of hair, its wide mouth red-lipped, nostrils flaring, somehow feral. A face done in broad strokes, square-jawed, high cheek-boned. A pagan face, not beautiful, and more than beautiful.

Young! But in the great dark pools of her eyes lurked something old as time—a fear ancient when these towering arboreal giants were seeds, wind tossed—a fear that must have crawled in the very womb of the world. And that fear was not of me!

I knew it, gasping for breath and clutching her arm in that moonlit glen—knew it as though some thought-current flashed between us. She was afraid, ghastly afraid, of something that stalked these woods. I knew then she had not sought our fire to warn or slay, but to seek sanctuary with us from some peril whose very presence hushed the tiny creatures of the wild.

A moment I swayed, the pall of her dread folding over me like a shroud covering us both—and then I cursed myself for a fool! For my eyes—dropping—caught a red device on her robe, over her heart—a red emblazonment of a rose, full blown, so marvelously worked it seemed alive. A full blown rose....

Anger surged up in me, gave me back my voice. "What is the Dance of Doom?" I gritted through clenched teeth. "What is it?"

The fear in her eyes flared—and suddenly was gone. Not a line in her face changed, but expression was gone from it, humanness was gone. It was a mask—chiseled from stone, and those eyes veiled, emotionless. She spoke, and her voice was without inflection. "I do not know."

"You damn well do! You left that note for me. What's it all about?"

Her lips tightened.

"By God," I mouthed. "I'll make you talk. I'll..."

Something stopped me—a crackle in the underbrush just behind me, a soft footfall. I twisted to it. And crouched, staring.

HE WAS tall, immensely tall, the old, old man who stood there, unmoving, and his seamed face was suffused with wrath. His deep-sunk eyes blazed from their hollow pits, the very hairs of his white beard seemed to writhe with a terrible anger. His thick cudgel was raised over my head. In instants it must come down and crush my skull. It quivered—a soundless scream tore at my throat! But it did not fall.

Instead, from behind the screening of his beard a booming voice filled the forest with hollow sound. "Stranger—your way is barred!"

The thick staff did come down, now, but slowly. It came slowly down till it pointed straight at me. "Go back! Leave the forest. Or you will surely tread the Dance of Doom!"

I was crouched, gaping at him, gaping at the bony, skeleton hand that clutched his stout club, gaping at the white robe that cloaked his giant form. I could not force my eyes up again to meet this blazing ones—dared not. For I knew that if I did I was lost. Even so, even with my eyes fixed on the red rose over his heart, terror shook me as a dog shakes a captured rat.

And then—perhaps the extremity of my fear broke down in a small measure the barrier between two worlds—I seemed to hear my father's voice: "The devil himself couldn't stop Hepburn—the devil and all his imps. He'd claw the heart out of Lucifer quick as shooting if he tried to bar his way." Dad had drummed the saga of the old Tiger's deeds into my ears till they had become a very part of my soul—and now his wisdom was justified. Fear seeped out of me. I straightened.

"Go back—Like hell I will! I'm putting a railroad through here, and you, with all your nightgown flummery and red rose monkey business, can't stop me!"

If anger had reddened his eyes before, a very hell of fury flashed from them now.

"No railroad shall ever profane this good ground," he said.

"No?" My muscles tensed, ready to grab his stick if he made a lunge at me, and my voice held steady. "Try and stop me!"

"You persist?"

I thrust my jaw out and met his blazing eyes with my own. "Yes!"

"Then you must dance!" He took one backward step and was gone in the darkness of the clumped trees.

Curiously, I could not hear him go. But those last words of his rippled fear up my spine again. Not because there was a threat in it, but because there was pity. Pity and an odd sadness. It was as if he were sorry for what was going to happen to me.

I looked around. The girl was gone, too, of course. I had let go of her when the old man appeared, and she hadn't waited. I couldn't get her out of my mind. That look in her eyes...!

I'd better get back to camp and wake up the boys. This thing wasn't over yet, not by a damned sight. There was a gun somewhere in my pack, too. I'd be more comfortable with the feel of that in my hand.

I started off—and stopped. Which way was the camp? Up or down? To left or right? I hadn't the slightest idea. I didn't know which way I had run, chasing that girl, nor how long, nor how far. I might be right on top of the clearing, or I might be miles away. I bit my lip, tried to think. No. I couldn't remember.

I CURSED. Nothing to get scared about, for I could always get

to civilization by going downhill. But that wasn't what bothered

me. This damn nonsense might hang up the survey days. And I had

to get my report in in forty-eight hours. If I didn't, Wolf

Hooper would have the L.T. & C. under his thumb again and the

Tiger's whelps would be licked for the last time.

It was twenty years, almost to the day, since Hooper had smashed John Hepburn, taken the Louisiana, Texas and California away from him, and sent the old fighter into the limbo of some sanitarium for the mind-weakened rich. Two decades had passed before the time was ripe for Hepburn's old crowd to stage the sensational stock-exchange raid that wrested the Tiger's road from its bondage to Southern Transcontinental, and started a new war whose next battle had been staged in Wiscardo's legislature. A battle that had bled Hepburn's boys white to win—if it had been won.

There was but one way to lick the Estey gang so that they would stay licked. If we could build a cut-off through State Park, over Dark Mountain, it would take ten hours from our running time and get back the traffic of which Hooper had bled us, the traffic we needed to stay alive. We had clawed a bill through that gave us the necessary permission—with a time limit. Hooper had sneaked that joker in, that time-limit of ten days to begin construction. And we must post a half-million dollar bond for completion before a shovel was turned.

The L.T. & C. treasury was almost dry. If the line could be run at ground-level we could post the bond, start grading, and clinch the franchise. But if it were necessary to tunnel—twenty miles of bore, that meant—we were sunk.

And that was what I was here to find out—had found out with only a shadow of doubt remaining. One more day's work and I could be sure. That was why I could not seek safety in flight down the mountain, why I must find the clearing and the camp.

Besides—Good Lord! What might happen to Art and Jimmy in the meantime? They were asleep—confident I was on watch. If I didn't get back....

What was that? A long wailing sound from my left—far off. There it was again, nearer. A wail that rose and fell, rose and fell, half-human, half—something else. Nearer still. A thin crescendo, vibrant with fear. A heavy body threshing through the woods. A gibbering howl. Words. Words I couldn't make out—but human words. The threshing, the wailing were thunderous now, were upon me!

Something crashed through into the little clearing, thudded against me before I could dodge it, sheered off. I saw horror-struck eyes, a white face. Jim Carle's face! He plunged on. I dove after him.

"Jim!" I cried. "It's Dan, Jim. It's Dan!"

He whirled—snarling. His mackinaw was ripped from his shoulder, his shirt was in shreds. There was a long knife-slash across his cheek. His hand was bleeding.

"Dan!" he gibbered. "Dan! They've got him—they've got Art." A sob ripped from his lips. "Oh God! They've got him! Come on. Run!" If I hadn't seen him talking I should not have known that squeak for his voice. "Run or they'll get us too!" He whirled, started off again.

I grabbed his belt, hauled him back. "Wait!" I snapped. "What happened? Who's got Art? What have they done to him?"

He jerked, struck at me. "Let me go! They'll catch me. They'll catch you! Come on! Run!" He was completely mad, insane with fear! He ripped a clawed hand across my face. "Let me go!"

"Let you go, hell," I grunted. "We're going back—back to help Art!"

"No!" he mulled. "Not back there! Not back to them! Never!"

Shane wouldn't have given up without a scrap. This—this yellow cur had left him to fight alone. I must go to Art—help him. But I couldn't let this terror-blind kid rave through the woods, alone. He'd be dead before morning, he'd bat his brains out against some tree. What to do?

"Let go!" He twisted and sank his teeth in my hand.

My bunched fist cracked flush on the button. He collapsed, sprawled. Clean out.

He'd be off again when he came to. Off again to death in the woods! I ripped his web belt from its loops, jerked free his wrap leggings. In seconds he was lashed, bound to a sapling. He couldn't get away, now, till I was ready to come back for him.

God forgive me! I bound him there, helpless, powerless to defend himself. But he knows I meant it for the best!

NO difficulty now about finding the clearing, for Carle had

trampled a plain path through the brush. I took it at a

run—through splotched light and black pools of shadow,

passed blacker bulks concealing an untamable threat. At last I

sniffed wood smoke and slowed. If they were still there—if

Shane was still alive, still fighting—only a surprise

attack could succeed. I dropped to the ground and crawled,

sliding almost soundlessly through the brush.

There was no sound from the clearing ahead.... A lump formed in my throat. I was too late—Art Shane was dead. I would never warm to his grin again. I stopped, and earth-smell was like grave-smell in my quivering nostrils.

Panic shrieked, gibbering, in my Brain. "They're waiting for you. They've set an ambush for you. Turn and run. Turn and run, before it's too late." I lifted—and stiffened.

I could not abandon Art. Perhaps he was not killed. Perhaps they had left him—whoever "they" were—lying out there in the clearing, unconscious, bleeding, dying. I must go on. I must know what they had done to him.

I started crawling again. And now a sound did come from ahead, a sound that rasped nerve ends of ancestral fear. A curious chanting sound. A blood-curdling ululation, rhythmic but unmelodic, that pulsed to me through the forest darkness, that beat to me, and around me, and within me, that thumped, thumped its savage rhythm within my very brain. Vague, ancient memories stirred in me, gripped me with primordial fear. I envisaged shuffling feet; brown, shuffling feet; aboriginal feet circling in a dance.

The darkness broke. I glimpsed red embers of a dying fire, just ahead. Belly to the ground I snaked those last few feet, inched my head beyond the last obscuring tree.

Red coals glowed, out there. I saw rumpled blankets, tossed aside; our piled packs; stacked instruments. But no sign of any human, no sign of Art Shane's torn body. Clear now, and loud, the savage dance song thumped against my aching eardrums. I forced my gaze to the clearing-center whence it came.

Moon-glow had broadened, making a lake of light that bathed the rock and filled the earthen ring. And in that ring a huge, stark-naked figure shuffled and swayed and postured in time to the pulsing, thudding rhythm of his own primal chant! He faced the great monolith as he danced, bowed to it in savage adoration, postulated to it in obscene worship of the bulking stone. His song throbbed in my veins, beat in my blood, till it was all I could do to hold myself from dashing out there and joining him in that primeval idolatry.

And then I saw the descending groove in the rock-face, saw that it was dark, that it glistened, wetly, a slow pool forming where it reached the earth. My eyes lifted. Mounding above the stone edge a black form bulked—a head lolled in the niche where the groove began. The head twitched. The form writhed.

"Art!" His name ripped from my throat and I was on my feet, was hurtling across the clearing. "Art!" Oh my God! Was Shane stretched atop that sacrificial stone? Was it Shane's blood that dripped so slowly down that damned groove? Horror hurled me at that dancing, savage figure. Horror and the lust to kill, to tear Shane's murderer limb from limb! "Art!"

The naked dancer whirled to meet me. I saw his face, his gibbering, twisted face.

This chanting savage, this aboriginal postulant, this nude sacrificant who trod the Dance of Doom, was—Art Shane!

I SKEWED to pass him, dug heels into the ground and twisted to

confront him again. His eyes were wide, glazed and unseeing.

There was froth on his contorted lips and his nostrils flared.

"Art!" I cried. "Art Shane! What are you doing? Art!"

He stared at me. His brow furrowed—then cleared. His mouth worked.

"They come," he intoned in a strained queer voice. "The Children of the Rose gather to the sacrifice. Earth drinks blood, rose-red, and the clan gathers. Come dance, brother, dance." His hands beat the time of his interrupted chant, and his body swayed. "The hour of Doom approaches. Dance, brother, dance."

Mad! He was staring mad! What had driven him so? He was no neurotic, no yellow-streaked weakling like Jimmy Carle. What horror had struck at him from the forest to drive reason from his mind? What was the sacrifice whose blood oozed down the stone?

A whimper answered me, a whimper and a low growl. I ventured a swift side glance. It was Joseph, the dog! Joseph, with his throat cut and his life-stream feeding the thirsty ground. Joseph, who quivered and died in the instant of my darting glance.

"Dance!" Shane leaped at me, grabbed my arms, trying to force me into his insane revel. "Dance!"

I thrust him away from me. "Art! Art Shane!" I shouted. "Stop it, Art!"

He reeled back to me. Somehow, hideously, his every movement kept time to the barbaric chant to which he had danced, the savage rhythm that still pulsed in my brain. He reeled back and pawed at me. "Dance, brother. Dance!"

No use. There was only one way to stop him. My fist jerked back.

But the blow was never completed. In that instant I was seized from behind! An iron grip clamped my wrist—swung me around.

I was in the clutch of the old man of the forest! Instantly, as his fingers had seized my wrist his eyes seized mine. They were deep, dark pools, into which my own gaze sank. They were all the world, and terror writhed in them. Suddenly I was powerless, unable to move, while a dull sense of utter defeat swelled within me.

His voice came from a great distance. "Stranger. Have you seen the power of the Rose of Doom?"

I heard a response. It must have been I who made it. "I have."

"Do you still wish to tread the Dance of Doom?"

My flesh crawled. I knew now, or thought I knew, what that meant. "No!"

"Is the way across Dark Mountain barred to you and yours?"

Almost, I said it. But something, some last faint remnant of will, stopped me. My teeth clamped on the word. For suddenly I knew that if once I voiced that "Yes," if once the syllable those compelling eyes demanded found form in sound, I was lost. I should be released—to stagger back down the mountain with that "Yes" deep planted in my consciousness. And it would find expression in a lying report to the men who trusted me, Hepburn's boys, my father's friends! "We cannot build over Dark Mountain. The way is barred."

But if I refused—I heard the gibbering of Art Shane behind me—felt the tom-tom of savagery in my blood. If I refused—would I become as he? The twin pools of hypnosis, into which my aching eyes plumbed to find only unending swirl on swirl of awful threat, held me captive. Fear hissed in my ears, "Say 'yes' and save your soul."

My neck corded, my veins were icy streams and my brow was cold with sweat. Tiger Hepburn would have sold his soul to build a mile of road. My throat worked, my tongue moved, and the word squeezed out: "No."

It broke the spell. "No," I shouted.

"No. We'll drive the line through in spite of your damned tricks!"

I jerked away from the old devil's grasp, leaped at him with fists flailing, reached him once. Then his club crashed down....

MUSTY earth-smell was in my nostrils, and the dank fetor of the tomb. Pain throbbed at the back of my skull, dull pain. I opened my eyes, blinked. A dim glow lighted rock wall, glistening with moisture, an arched rock roof, low-hanging. I tried to lift a probing hand to the agony in my head, could not. I was tightly bound. I was a prisoner—trussed like a hog awaiting the butcher's knife.

And what was I awaiting? The old man of the forest would never dare to loose me so that I might carry my story out of Dark Mountain. If this were not my tomb a grave waited for me out in the clearing, a grave like that in which rotted the corpse we had found.

I wondered if he would thrust a rose between my dead lips. "Roses in the moonlight...."

This wouldn't do. I must think, must try to find some way out. I was still alive, still in possession of my right senses. Poor Art! The ancient in the white robe was a hypnotist, that was evident; an adept at the art. He had almost gotten me, as he had certainly succeeded in getting Shane in his power.

Somehow that decision eased me. For death itself is not half so horrible as insanity. To see one close to you, one who has worked shoulder to shoulder with you, to see such an one mindless, a gibbering lunatic, is worse than to see him dead. I think it was the collapse of John Hepburn's mind that killed my dad. I shuddered again as I remembered Art posturing naked before that rock.

Slow footfalls paced slowly to my right, passed, came back again. The cave opening must be there. That must be a guard, posted to watch me. Was it the girl? Peculiarly enough, I realized I was anxious to see her again. The pagan beauty of her face was clear to my mind's eye, despite all that had passed since I glimpsed it. I could still feel the warmth of her slim body against mine.

I could move neither arms nor legs, but I could roll over. I did so, to the right. The mouth of the cave was just man-high. There was a rock wall opposite, a corridor of sorts, empty for the moment. The stone showed chisel-marks.

The footsteps came again. Someone walked slowly across the aperture, tall and white-robed. He glanced in.

"Art!" I exclaimed. "Art Shane!"

"Silence in there." He looked at me but I could swear he did not see me. His eyes were unfocused, their pupils unnaturally small in the dimness. "Silence!"

"Art. Don't you know me? It's Dan. Dan Hale."

For a moment his brow furrowed, as it had when I called his name while he danced. And, as then, the momentary effort was abortive. "Silence!" he said again. "He who has been chosen for the Dance of Doom must meditate in silence!"

He said it mechanically, in that odd, strained voice that was not really his... then turned away to resume his sentry-go.

Poor fellow! Somehow his fate seemed worse than mine. Was he destined to remain here forever, dragging out his life in a hypnotic trance, acolyte of God alone knew what horrible ritual?

Perhaps when the railroad came through he would be rescued—cured. But the railroad would never come through now. Not the L.T. & C. I should never return to make my report, Shane would not return. When hope for us was given up it would be too late for another survey to work through. Hooper of the Estey would build the line then. I groaned. I had let them down, the men who had fought to revenge the old Tiger. The men who had trusted me because I was my father's son, bore his name. I had let them down!

LIGHT flickered, out in the corridor, yellow light that

brightened as it approached. There was a faint whisper of nearing

feet. Shane halted, lifted his head, expectantly. A candle, held

in a white hand, appeared at the doorway edge, then a figure, a

face. Brown hair rippling over shoulders white-clothed. The girl

of the wood. The girl whose face I had wanted to see once more

before I died.

Art advanced to meet her. "Is the hour of Doom at hand?" he intoned.

So that was what brought her here! She was the messenger of Death. Yet I did not care. What was the difference, she or another?

"Not yet!" Flat and inflectionless, the words dropped from her lips. "But it approaches. Have patience, neophyte." I noticed that she held the candle at arm's length, that its flame quivered nearer Shane than her.

"The call has gone out and the Children of the Rose gather," she said. Her voice dropped, I couldn't make out what she said next, but apparently she was giving him instructions. Art bent forward to hear her better, and for a moment they conversed thus, those strange, white-robed figures.

Then abruptly Shane reeled, flung out a hand to the wall, fell against it, slid down along it to the floor. The girl flung the candle from her, whirled, and came into the cave. In her other hand, that had been hidden in the folds of her robe, a knife glittered. She knelt to me, and the blade lifted, poised....

Sudden enlightenment soared through my brain. She was the executioner! A hypnotised man will not kill; they had feared Art's interference at the last. The candle's flame was drugged—he was out of the way—and now—

I jerked away, rolling. Useless to fight. I could not escape. But moments are precious—when they are the last you will live....

"Don't," she whispered. "Don't. He may come!"

Astounding words! I stared at her. What did she mean? "Who?" I croaked, inanely.

"Hush. Oh hush. Don't ask questions. Let me cut those ropes!"

Then—then she had not come to slash my throat. She was rescuing me! Before I could recover from the shattering realization it was done. I was free!

"But why—why?"

A soft hand went across my mouth. "Don't ask questions. Hurry. There's a chance—a tiny chance we may get out before he misses me." But I was answered. Her dark eyes were no longer mute, expressionless. Nor was it fear that made them starry.

And a leaping warmth in my own pulse responded to what her eyes told me!

"Oh, hurry!" She was insistent. "Follow me—and be very quiet. If he hears us—"

I got to my feet, winced as returning blood needled my limbs.

"I'm Dan Hale. Who are you?"

"Call me Nina. But come."

She was out of the cave. I followed perforce, stumbled over Shane's limp body. "Wait, Nina," I said huskily, and bent to it, heaved it to my shoulders. It was a staggering weight.

"Leave him!" she whispered. "You cannot escape with that load."

"No! He's my friend. I cannot leave him. Go on."

Just outside the cave mouth was another opening into the ground, and this we entered. It was a maze of rock-walled tunnels she led me through, a labyrinth I could never retrace. Towards the end I don't think I even saw them, so agonizing had become Shane's weight on my bent back. If it hadn't been for her hand on my arm, her whispered encouragement, I should never have made it. But at last we crawled out through a jagged hole and I felt the clean coolness of the open air again. It revived me.

"Where now?" I gasped, easing my burden against the vine-covered embankment that was all that showed of the underground system out of which we had come. The moon was almost at its zenith, and in its flooding light it seemed that every needle on the towering pines showed distinctly.

"Wait," Nina breathed, and crouched, listening. I listened also, and could hear nothing but the soft sough-sough of the breeze through dark foliage. But suddenly the girl put out her hand. "Down!" I could scarcely hear her. "Don't breathe."

Something of her panic communicated itself to me and I dropped, tensed. Just in time. For in a moment I too heard the soft pad-pad of footsteps and, not ten yards away, saw a form flit by, an unbelievable, ghastly shape!

It—whatever it was—man, woman, or something evil evoked from the forest mists—was swathed in white; legs, body, even its head wrapped in a tight white covering through which only the eyes were visible. It glided through the trees somehow unhuman, with scarcely a sound except that soft pad, pad of its swathed feet. And in one white-covered hand it held a single rose—full blown—like a globule of blood.

"Good Lord!" I turned to Nina fiercely. "What is it?"

SHE looked at me despairingly. "That was a Child of the Rose.

They are gathering for the Dance of Doom. The moon is full. He

has called them and they are gathering." She was close against me

and I felt her shudder. "I am afraid we are too late—the

forest is thronged with them."

"In God's name who are these Children of the Rose? What are they? What is this Dance of Doom?"

"I—don't know. I have been here with him as long as I can remember, but always he has made me keep to my cave on the nights when the Children dance. It—it is something horrible—that I know. For the sounds that came to me from the forest on the nights of the full moon—" She made a gesture, that, and the look that peered from her eyes, told me enough.

"He! Whom do you mean? The old man?"

"Yes."

"Who is he?"

"I think—he is my father. He must be, he has been so very kind. Only in the last week he has changed. He has been moody—curt. I have been frightened. And today he told me that it was time I joined the Dance of Doom." Her eyes widened. "His face was terrible when he told me. I—I wanted to run away—but I did not dare. Then—then I saw your fire, and—"

I put my hand over hers. "I know. I rushed at you like a madman and scared the wits out of you."

"You could not have known. But—when I saw you—when you held me—I knew I had been waiting for you—all my life."

She said it simply, like the child of nature she was. And I thrilled to it. Words rushed to my lips. I choked them back. Time enough for that when we had won through. I took her hand, held it tightly.

"I know a path down the mountain that is hidden," she said after a moment. "Shall we try it?"

"We'll have to," I answered. "It's suicide to stay here." I had my own ideas about what the Dance of Doom entailed. I hadn't forgotten the grave in the clearing, nor what the hypnotised Shane had done to the dog.

"All right," she responded. "Come."

I turned to lift Shane again, and hesitated. Our progress through the forest must be swift, swift and stealthy, if I were to get Nina away. Carrying Art would make that impossible. We would surely be traced and caught. Dared I leave him?

"We could throw these vines over him, hide him." Nina's low voice chimed with my thoughts. "I think he will be safe till morning, and then the Children of the Rose will be gone."

I nodded slowly. No use sacrificing all of us in a vain attempt to drag him along. He'd have to take his chances. I got the thick leaves over him and turned away.

"Come," she said.

The girl stole through the woods like a shadow, but my own clumsy progress seemed to be thunderous. We seemed to be to one side of the clearing. I was tensed, quivering. Every tiny sound, every leaf rustle seemed a threat. Once Nina dropped to the shadow of a bush. I dropped too, and another of the white-swathed apparitions showed momentarily among the trees. He passed, and we started off again.

Then we came to a trampled swathe through the brush, and I stopped. "My God!" I burst out. "I forgot."

She whirled to me. "What is it? What is it, Dan?"

"Jimmy, Jimmy Carle. I left him—off there—bound to a tree."

"Jimmy? Who....?"

I explained, quickly. "We've got to free him, Nina," I said. "We've got to."

"But...."

I turned down the path that marked his frantic flight. There was no time to argue, no time to debate. It would be murder to leave him there, bound, helpless. And it was only a few steps.

"There he is!" I exclaimed.

He was slumped against the lashings, his head sunk forward. I got to him. "Jimmy!"

He did not stir.

"Jimmy!" I stooped, put a hand on his shoulder. His head rolled away from me. I saw blood—a great gout of blood, already dry, dyeing his neck, his shirt front. His throat was slashed to the bone. And in his mouth—good God!—in his mouth a red rose was thrust, full blown!

A scream—stifled—close behind. I twisted. Nina was struggling in the arms of a white-swathed ghoul. Another was leaping at me. I lunged to meet him, my fist arcing. It never touched him! For another and another of the old man's masked followers swarmed on me, swamped me, bore me, threshing, to the ground. As I fell I saw the bearded ancient himself, eyes flaming and cudgel upraised, towering above me.

I WAS in the prison-cave again, lashed now beyond hope of escape. But I was not alone. Nina was there too, a prisoner, helpless as I. And from somewhere outside, faint, but clear, came a pulsing that I recognized. The chant of the Doom Dance, throbbing, thudding, pounding its unholy rhythm into my quivering brain. But it was not one man alone that chanted the savage paean—it was a throng of white-swathed, ghastly fanatics. I had seen them, heard them, as Nina and I were carried back into this rocky maze from which we had thought to flee.

We did not talk, I and this girl I had found only to lose again so soon, so horribly. Only our eyes clung, drank each other in. We dared not speak... for dread was a crawling, live thing in that cave. There had been no mercy in the old man's face as his voice had boomed, out there in the forest glade, just before they bore us away: "She who would rob the Rose must feed the Rose. The good ground will drink deep tonight."

A footfall thudded, in the entrance behind me. They were coming for us. I tried to smile at Nina.

"Hale!"

I rolled over at sound of Art Shane's voice, his old voice, and hope flamed within me. I stared up at him. He was still in the robe of the Children of the Rose, but his eyes were no longer dazed. Had he come out from the hypnosis that held him—had he come to save us?

"Nasty fix you're in, Dan. Nasty mess." There was something gloating in the way he said it, something reptilian. But surely he was normal once more.

"Looks like it." I said steadily enough.

"There's a way out. If you're not a stubborn fool." His words dripped down to me, dripped down from a mouth that scarcely moved. "You just have to say the word."

"What do you mean?"

"Look?" He pulled the flap of his robe open. Beneath it he was fully clothed, and two holstered automatics hung from his belt. "Those nuts aren't armed—I can shoot a path through them. Promise me to report that the route over Dark Mountain is impossible, and I'll do it."

The floor heaved under me, and my head swam. "But it is. You know it, man. It's easy."

"Know it? Hell! I knew it a month ago, when I surveyed the cut-off for the Estey. That's when I ran across the old bird in the night-shirt and fixed up this little entertainment for you."

"Then you're—"

"Working for Wolf Hooper. Sure, now you got it. Did you think he laid down on the job when the bunch of paupers that sent you out licked him at the State House? There's twenty grand in this job for me, and I'm a ring-tailed pussy-cat if I haven't earned it."

"You're telling me the Children of the Rose are fakes!"

"Oh, they're straight enough. I come from this neck of the woods; always knew there was some kind of cult up here that had the idea Dark Mountain belonged to them. So when the boss nut popped up I knew just how to play him. Fell right in with him, admitted the way was barred, kidded him good and proper. When he put it on me would I join his outfit I jumped at the chance. Reckoned I could use them if we lost out on the franchise. Figured on scaring out anyone the L.T. & C. sent to look things over."

I tried to throw the contempt, the horror, I had for him, into my eyes, my voice. "You inflamed them to murder to win your filthy pay!"

He shrugged. "I didn't think it would come to that," he said, "but you were mulish and they got out of hand. What the hell! It ain't the first time guys have been croaked in a scrap between the two roads. Tiger Hepburn did plenty of it in his day."

"But that was clean fighting, with an even chance. This...."

"Cut the gabbing. What do you say. Promise?"

It was Hobson's choice—whatever my answer would be. Either way we were licked.

"If I agree," I questioned, "you get me and Nina out of here?"

"Hell no! I'm not including the girl. I'm not taking a chance on her—she might ball up the works. The two of us will have a tight squeeze as it is."

A red haze swam across my eyes. "You rat!" I snapped. "You can go to hell!" To save her I might have made the rotten deal. But now....

He licked his lips, grinned. How could I ever have thought his smile pleasant, friendly?

"Just as you say, Hale," he laughed, "I like it better this way but I though I'd give you a chance. When this is over, I'll go back and make the report myself. Boy, how I will weep when I tell them a landslide buried you and Jimmy."

The chanting was growing louder, closer. Shane looked furtively around and slipped away. I had time only for a whispered, "Heads up, sweetheart," to Nina before the obscene procession appeared. A long line of white-swathed mummies pranced in, circled around us. Two bent to me, two to Nina. They lifted us and a long animal howl punctuated the horrible rhythm of their hymn.

THE clearing was a bowl into which the moon, almost overhead, poured merciless light. I lay, trussed so that I could not move, on the flat top of the monolith. Another bound figure was feet away from me. It was Nina, but she was outstretched in the oval depression whose use I had guessed, ages ago it seemed. Her head overhung the rock-edge, and her neck lay exactly in the jog that nicked it. Squatted at my side, making doubly sure I could not escape, was Shane—his eyes unfocused once more, his lips twitching in time to the swelling pulse of the dance. And above the prostrate girl loomed the tall, weird form of the bearded leader of the cult. Looking up at him, I fancied he towered to the very sky. In one gnarled hand a long, keen knife caught the moonlight, and at his feet two red roses lay.

But at the moment the terror of the scene focused in the earthen ring below and about the rock. They were circling about us, faceless, bodiless myrmidons of the Rose, circling and posturing and dancing, in a primeval measure whose utter abandon paled to mildness Shane's solitary prancing that had held me horror-stricken not an hour before. And from their hidden, muffled mouths came the chant of Doom, the thudding, thumping, booming voice of antediluvian fear, the murder hymn to some mad idol conceived by the crazed brain of the ancient. It was the voice of the wild itself—the very trees seemed to dance to its awful pulse—the very mountain to heave in its primordial rhythm. It was the quintessence of savagery, it was civilization abandoned, the triumph song of the ancient nature gods, come back to claim their own.

Suddenly it hushed—and silence thundered in the glen. I saw that the bearded priest of the lost religion had raised the knife—that he was quivering with some strange ecstasy. For a moment the silence held—then his voice boomed into the quiet:

"Children of the Rose, the night-orb nears its zenith—the moment of Doom is at hand. The good ground is athirst—and it shall drink deep. The good ground is athirst—and its thirst shall be slaked with the blood of him who would bind it with thongs of steel. Its thirst shall be slaked with the blood of her who is apostate to the worship of the Rose. Children of the Rose—shall the good ground drink?"

And in a muffled, awful chorus the white-swathed, mouthless devils responded: "Let the good ground drink."

The ancient knelt, his knife poised over Nina's throat, his bearded face upturned to where the glowing disk of the moon was within a hairline of the meridian. In my ear Shane whispered, "What say, Hale? There's time, even yet. When he drives in the knife... They won't notice us."

"Go to—"

Just then the old man's free hand moved—crept up alongside his bearded cheek—and pulled at the lobe of his ear!

In that instant, faced as I was with death, this gesture of the madman struck me as if it had been a blow. Dad's oft-repeated words came flocking back to me. John Hepburn, insane, still lived. The old man's fierce glare of anger, like no other living man's... was he... could he be...? Or was I going mad myself, mad from the certainty of doom...?

"Hepburn! John Hepburn! Tiger Hepburn!" My voice was a blast in that stillness. "Hepburn! He's a Hooper man! There's a Hooper man here! A Hooper spy!"

The old man jerked to me—and I saw sudden light blaze into his eyes. "Dan!" he said fumbling. "It's Dan Hale's voice!"

"John!" I took the cue. "John Hepburn! I'm Dan Hale. Wolf Hooper sent this fellow! He's an Estey spy."

Then Shane made his mistake. If he had kept quiet—or brazened it out.... But he sprang to his feet, tore the robe from him, reached for his guns. The old man—Tiger Hepburn—leaped for him, his knife flashing.

Shane got one gun out and it blazed. The Tiger jerked back with the impact of the bullet, folded, and sprawled across the stone. The knife slid from his flaccid hand, slid over the stone edge. John Hepburn had died as he had lived—fighting Wolf Hooper's men.

Shane whirled to me, his gun snouting.

"You dog," he gritted. "You won't—" He stopped short. A white wave was breaking over the rock-top, a ravening white wave of swathed, horrible figures, more horrible now for their snarling, animal-like baying. Shane's gun thudded, but a mummy, plunging between, took the lead death meant for me. The others shrilled, "Kill! Kill!" and Shane vanished under the white torrent.

I heard the body-muffled crash of his gunfire, once, twice. Then, as bandaged; plunging feet spurned me, kicked me from the platform, I heard him scream. That piercing agonized shriek rings in my nightmares, even now.

I rolled over, thudded to the ground, and felt a searing pain in my side. While that bestial chaos still raged overhead I twisted to see what had cut me, and sudden hope blazed across my swirling brain. It was the old man's knife! In cutting me it had sliced the rope binding me, loosening it just enough that I could jerk, get fingers on the black hilt, cut the bonds about my ankles.

I heaved to my feet, my wrists still lashed together but my arms free and in front of me. The knife was grasped in my taut knuckles.

They had shoved Nina aside, near the edge, were dragging what was left of Shane to take her place at the sacrificial niche. They were intent on their gruesome task—did not see me reach up and slice that keen-edged blade through the ropes around her, did not see her roll off into my arms and join me in headlong flight to the shelter of the forest.

We got safely into their welcome gloom—but none too soon! For behind us a great shout arose:

"It drinks. The good ground drinks!"

I dared not glance back, but in my mind's eye I could see that dark groove, wet and glistening, could see the dark-red pool gathering on the earth below.

As we stumbled through the trees, clinging together, sound followed up—thudding, thumping, rhythmic, horribly rhythmic, the chant of the Dance of Doom. It pulsed through the darkness of the woods; throbbed its savage, unmelodic cadence through the forest aghast; throbbed in my blood, in my brain, till the whole world seemed to beat primordial horror into my very soul.

Then Nina drew closer to me. I felt the warmth of her dear body, and my blood throbbed with a new rhythm.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.