RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

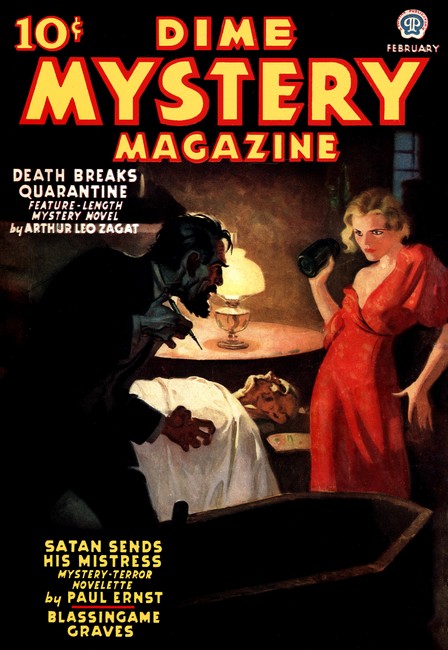

Dime Mystery Magazine, Feb 1937, with "Death Breaks Quarantine"

EDITH HORNE returned to the home where she had known only peace and love, to face the ghastly mystery of her neighbors' vicious hatred and the black horror of her father's deadly madness...

Edith Horne slid furtively through the rank underbrush of Uriah Scantell's abandoned orchard, the old guilt at being on forbidden ground quickened her pulse with a familiar mingling of excitement and quivering apprehension. The eerie shadows, the gnarled limbs of the ancient trees reaching out for her, the brooding hush, took her momentarily back through the years. Fleetingly again she was a little girl with smudged face and yellow pigtails, very much frightened, because against her father's strict prohibition she had ventured to the neighboring property on the wrong side of Dark Pool, terrified lest Scantell should leap out at her now, now, out of the murk, and...

She had never learned what it was old Uriah might have done to her had he discovered her on his land. All that was long ago, and now she was Edith Horne, R.N.; three hard years of hospital training ended, the coveted diploma hers at last.

Sunlight filtered through the leafy edge of the thick woods. Edith paused to smooth her white frock over the tender curves of a slim form just burgeoning into womanhood, and adjust the misty glory of her hair with fluttering, birdlike touches of her deft hands. The freckles of that long-ago tomboy were piquant, faint tracings now on the downy velvet of her skin, and the turbulent tempestuousness of her eyes had become a calm, deep blue. But her little nose was still saucily tip-tilted, and her red mouth still quirked with the impish mischief that had inspired her notion of surprising her father with her return.

To make sure the village gossips would not see her and 'phone the news of her arrival to Jeremiah Horne, Edith had slipped off the train on the side away from Wellton's little depot; had darted into the bushes and made her way by back lots to the wheatfield just ahead, where she knew Dad would certainly be on this late fall afternoon.

She had such glorious news to tell him. News that was still a secret between herself—and Harry.

"My Harry," the girl whispered, her eyes aglow. It was still incredible that Dr. Harold Gorton loved her. The idol of Midwest City Hospital, he was the medical board's pride because of the fame to which he had attained despite his youth; the adored of the nursing staff because of his youth, his tall, lithe body, his grave, handsome countenance and his unfailing consideration and courtesy.

No. Edith could not yet believe that he was her Harry, her sweetheart, her husband-to-be.

It would become real only when she had told Dad about it, and had seen his leathery, weatherbeaten countenance alight with joy in her happiness. She knew just what he would say.

"I am glad, Edie, glad." Then the light would die out of his keen old eyes. They would grow strangely somber. "Let us thank God," he would whisper, kneeling on the stubble of the cut wheat, "and pray that He will not ask too great a price for this joy."

Edith had never dared ask why he always said that, just as she had never dared ask why he so hated Uriah Scantell, his nearest neighbor. The two circumstances seemed somehow tied together, and somehow tied to the death of the mother she could not remember. And the roots of it all were buried in the dim past ...

Her hasty toilet was finished. She took the few more steps that brought her to the orchard's boundary, pushed through the final bit of brush.

The landscape drowsed in the heat of the setting sun. From beneath the girl's feet a grassy slope rolled gently down to the green-scummed surface of Dark Pond, whose nearer edge was the boundary of the Horne farm. Beyond it a languorous breeze whispered in tall, ripe wheat.

Edith froze. The wheat shouldn't be still standing like that, a rippling golden lake. It should be cut and sheaved, and Dad should be working down the long rows of shocks, pitchforking the bundles of grain into the wagon that Elmer Barnes, his hired hand, would drive off to the threshing.

Neither Jeremiah Horne nor Elmer were there. They were nowhere in sight. Edith could see the tall barn beyond the fields and a corner of its yard. The gate rails in the barnyard fence were down. A spade lay on the ground, as meticulous Jeremiah would never have left it.

It was wrong, all wrong.

Edith was running, suddenly; apprehension, dread, tightening her throat. Dad must be ill, dreadfully ill. She had not had a letter from him in over a month. She had thought him too busy with the harvest to write.

She skirted the edge of the desolate pool that had neither visible inlet nor outlet. An iridescent, rainbow film shimmered over Dark Pond's surface, and its slimy decay was an oily stench in her nostrils. A canvas tube snaked out and crawled to a gasoline-driven pump rusting nearby. Dad, then, had at last gotten around to draining the pond. But the pump was idle.

Now she was running through the wheat field that should have been a field of short stubble. The sunlight was a flood of hot brightness beating about her and the country-bred girl saw, even in her breathless haste, that the grain was not ripe but overripe. Her last lingering hope died that the season might be late, the wheat not quite ready for reaping.

The sere stalks broke crisply as she thrust through them. Crackling barbs caught at the light stuff of her dress as if a million tiny hands were striving to hold her back. The lush black loam of the fertile bottom-land clogged her trim, high-heeled shoes that were meant for the city's sidewalks...

She ran through the gap in the barnyard fence, flew past the tall, grey silo tower that had hidden the farmhouse from her.

"Dad," Edith called. "Dad! Where..."

The cry died in her throat, fading to a whimper. She was no longer running. She was standing stock-still in the old familiar barnyard. She was staring at the rambling, low building that was familiar as only one's birthplace can be—yet was suddenly eerie with a brooding, ominous strangeness.

One hand lay, pallid and cold, on her heaving breast, the other was flung, palm outward, against her trembling lips. Her eyes strained unnaturally wide, their pupils great wells of dark foreboding.

The roof's mossy shingles, the weather-stained fieldstone walls of her home, baked in the heat and the glare. But every window Edith could see was tight-shut, its black shade pulled tight down to cover it. It was as if the house had shut its eyes on terror—or as if it hid some dreadful secret within it from the sun's prying gaze.

"Dad," Edith moaned. "Oh, Dad." There could be only one reason for the drawn blinds, for the thick silence that folded over field and barnyard and house. Her father was dead... Why hadn't they let her know? Why hadn't Doctor Rawlins, Welcome Valley's beloved physician, wired her?

She didn't realize that she had moved until her hand was on the knob of the back-door, tugging at it. The portal did not yield. It was locked. It was bolted from the inside.

There was no sound from behind the door. No sound at all. That wasn't reasonable! No matter how suddenly death had struck, no matter how short a time ago, the neighbor women should be within, preparing the house for the funeral. The village men should be there, in unaccustomed black coats and neck-chafing collars, extolling the virtues of the departed in hushed, rumbling voices. There should be life in the house, the hushed murmur of life in the presence of death.

Instead there was the empty, awful silence of a sepulcher.

Abruptly Edith was aware that she was not alone. The fearful certainty that someone was watching her, that some hostile gaze was upon her, slid into her consciousness. She was—afraid!

She turned, slowly, fearfully. No one was in the barnyard, in the slice of wheat lot beyond it. Then she saw him—a sharply outlined figure against the sky, at the crest of the ridge beyond which was Scantell's homestead. He ducked out of sight in the instant she glimpsed him. Edith retained an eerie impression of the vanished shape. It had seemed weirdly distorted, not quite human...

The girl shuddered, icy with terror of the unknown.

This was nonsense, she berated herself, her small fist clenching. The wind had swayed a distorted bush up there, and it had swung back... She must get into the house, must find out what had happened to Dad.

THIS door was bolted from the inside, but although she had

cached her suitcase in the bushes near the railroad, she had the

key to the front entrance in the square little kitbag hanging

from the crook of her arm. She started around.

The great double window in the narrow south end of the house was as blind as the others. The front lawn was unkept, uncared for. A high row of close-planted hemlocks hid the road. But the sense of isolation the dark hedge conveyed was broken by tall, drab poles that stalked away down the valley with their burden of telephone and electric wires, tying the Horne farm to Wellton.

Their reminder that she was not utterly cut off from her kind gave Edith courage to mount the porch steps and fit her key into its slot. The lock clicked under her twisting fingers. The door swung open, thudded shut and locked itself behind her. Dad had been so proud of that spring lock, the only one in the valley...

A strange grey twilight, little better than darkness, brooded in the big sitting room the girl entered. Remembered furnishings were vague, menacing bulks in that eerie gloom. The low, raftered ceiling hung over her with a ponderable, tangible oppression. Closed in by thick stone, sunless for an unknown length of time, the atmosphere was heavy, dank with a damp chill.

But it was a smell that brought back all Edith's foreboding, that multiplied it tenfold, so that fear penetrated to the very marrow of her bones. The air was saturated with it, crawling with it. It was an acrid, stale foulness such as a fungus gives off, yet its staleness was not that of a fungus. It had some quality in it of a cadaver's putrescence, yet it was not the odor of the unburied dead. It was a stench beyond experience, beyond analysis. It was the very essence of horror.

"Edie!"

Edith wheeled, startled by her father's voice.

"Edie!"

It came from the point where she knew a sofa stood against the further wall, and it was a hoarse croak shot through with suffering. "How—how did you get here? Didn't—they see you?"

The girl took a step further into the room. "No one saw me... But you're sick. You—"

"Then get out. Before anyone knows you've been here. Get out!"

He was ill, delirious. God! And left alone here to die!

"Of course not." Edith forced a laugh. "I'm staying here to take care of you." Her fingers closed on a shade cord, "Let me look at you." The blind rattled up. Light blazed in...

Jeremiah Horne screamed, the sound shrill and unhuman with unendurable agony. He leaped from his cocoon of grey blankets.

The thing that scuttered toward her was not her father! Couldn't be! It was contorted, misshapen. It thrust her aside, fell against the window sill. Twisted, grotesque talons snatched at the shade edge, ripped the blind down. But in the frenzied instant before the sun was again barred out, every detail of the shrieking creature had burned itself into Edith's retina.

Horror throttled her, so that her scream was only a toneless rasp in her throat.

JEREMIAH HORNE crumpled, as the shade blotted out light. Pain's fierce strength that had lifted him from his pallet and flung him across the room was gone, and he was a sodden heap on the floor. Only his tortured hands moved, clawing over his eyes while his scream faded into a slobbering moan.

Edith Horne was just as motionless, the connections between her shocked brain and her quivering muscles jangled and broken. She stared at the whimpering mound at her feet out of eyes wide- pupilled and livid with horror.

The nurse was no stranger to broken bodies, to bodies swollen with dropsy, emaciated by fever, riddled with cancer. For three years she had ministered to them. She had schooled herself to callousness at sights that would turn the layman sick with revulsion. But here, in her own home, in the person of her own father, was something beyond her experience. It was a phantasm out of the half-world of nightmare, out of the delirium of madness.

It was barely discernible now in the restored dimness, but she had seen it with awful clearness against the light. It was a weazened travesty of a human form, every bone awry, every joint a swollen knob. Dingy pajamas had fallen down along a contorted arm, had flapped open on a rib-corrugated torso, exposing skin that was like no human covering but an integument of fishlike scales; dark brown and crusted, except where here and there it had sloughed away to expose weals of raw flesh.

The face had been most hideous of all. Out of the stiff grey- black hairs bristling on the sunken-cheeked, tortured visage, impossible great eyes had bulged from between granulated, hairless lids: eyes that were scarlet, blood-engorged balls pricked by the pin-points of too-tiny pupils. It....

"Edie!" That her father's voice should come from that horrible caricature of a body was somehow incredible. "Did I touch you?" It was a husky croak. "Did I....?"

"I—I don't know." The shuddering girl was amazed that she could manage speech. "I don't—know."

It must be her father who lay there. It was her father. Not only the familiar voice, but a vibration deep within her of filial instinct, of that love which cannot be deceived by any disguise, told her that. Pity welled up in her grief, vanquishing the revulsion that was still a sick quaver in her veins.

"It was the light," he moaned. "Stabbing my eyes with such awful pain. I didn't know what I was doing." A sob choked him, then he was continuing, more calmly, more reasonably. "But you are not sure whether I touched you. Maybe I didn't. Maybe you're safe yet. Go, Edie, at once. Go the way you came. And tell—no one—you have been here."

"Go?" The paralysis that had held her was gone. "And leave you alone?" She knelt to the worn rug, to the contorted figure that lay on it. "Do you really think I would. Dad?" Her arms reached out.

His grotesque hands battered feebly at them. "Don't touch me! Don't. You'll catch it!"

Edith had his head in her lap. Her arms were around him. "No I won't. Dad. I'm a nurse. I've taken care of people with the most terrible diseases, and I've never caught them. I know how to protect myself. And—" her tone was a low soothing croon—"and I know how to take care of you. Everything's going to be all right. Everything."

And at that moment someone laughed.

EDITH'S head jerked up. There was no one in the room.

Nothing moved. But that low, mocking laugh had been distinct. It

had come—but that was impossible—out of the wall to

her left. Out of the wall she knew to be solid stone, feet

thick!

She thought, perhaps, her father hadn't heard it. She went on murmuring to him as though nothing had happened. "Your Edie's here to take care of you, and you'll be better soon." She had not imagined that laugh. She had heard it. Fear breathed its icy breath on the nape of her neck, but there was no quiver of fear in her soft voice. "You'll be better..."

"Oww...." The cry from Horne's cracked lips stopped her; it was an animal howl of the purest anguish. Tiny muscles knotted with agony under brown scales that made his face a mask of horror, and he writhed in a paroxysm of fierce torture. "Owwww...."

Edith's teeth sank into her under-lip as she suffered with the man who had been father and mother both to her through the long years. Horne's fingers curled, clutching empty air—clutching the small bag that was somehow still on her arm.

The bag—! It was a graduation present from Harry—there was a hypodermic syringe in it, ampules of emergency drugs in solution. Of morphine.... She could give Dad relief! Thank God, she could give him relief from the pain that was driving him mad.

She had to slide him from her lap to get free. Then swiftly, dexterously, she had the needle adjusted to the glass barrel of the syringe, had it filled with the blessed anodyne.

It took all her strength to hold his flailing arm still while the gleaming steel point slid into a vein. She pressed the plunger home.... And in a few minutes—an amazingly few—he was asleep.

He would sleep for hours now. At least she had been able to do that for him....

She must get him to his bed. He was light, as she lifted him. Pathetically light. He was a mere shell of his former self, burned out. Realizing it, the girl knew that it was only her father's indomitable will that had kept him alive.

There was a glass of water alongside the sofa where he had been lying, and on the seat of a chair within reach a strip of dried beef, gnawed at one end as a rat might have gnawed it. Depositing her burden on the makeshift bed, Edith understood why Jeremiah was lying here and not in his room upstairs. He had grown too weak to negotiate the stairs. From here he could crawl into the kitchen when hunger and thirst had become too great. There was a faucet in there, the water that ran from it piped from a spring far up the hill behind Dark Pond. There were shelves filled with jars of meat and preserved vegetables prepared each fall for the ensuing year.

He could not blindfold his eyes against the light that agonized them so. He had to be able to see, if only a little, on his painful expeditions for the necessities of the life to which he clung. That was why he had drawn the shades.

How was it he had been left alone here so long? That was not the way of Welcome Valley. They were good neighbors here, helping one another. Even if he had been stricken unawares, there had been the telephone in the hall outside by which he could have summoned aid. There had been Elmer Barnes...

Where was Elmer? What had become of him? Why hadn't he...?

Something rolled out of the blankets Edith was straightening, and thumped on the floor. She bent down to it, automatically. Then there was nothing automatic about her gasp, her wide-eyed stare at the thing that was cold to her fingers.

It was a revolver. It was Dad's revolver. He was keeping it here, close by his side, ready for instant use. Why? Against what possible enemy?

A footfall thudded, close behind her! Edith whirled, the gun jerking up....

The room was empty. It was starkly, staringly empty. But fabric slithered, nearby, against some rough surface...!

Edith's scalp tightened, the brooding ominous silence closing in about her. There was no one in the house. She was alone in it with the pitiful sufferer who was the father she loved. But she was not alone! The certainty that someone, some thing, else inhabited the wan gloom that pulsed about her with the throb, throb of her own terrified pulse, was a creeping shudder in her veins, a chill wind breathing on her hot skin. Fear dwelt here, invisible, intangible, but a menace appallingly real.

EDITH HORNE had, after all, been trained in the hard, cold reality of science. She had learned how investigation and logic had demolished one superstition after another: the myth of spirit-possession, the tradition of bleeding evil humors from a diseased body—and her own childish belief that warts were acquired by handling toads, and that killing a toad would do away with them.

This training came to her rescue now. There must be, she reasoned, some quite natural explanation for what she had heard. The laugh. The footfall.

Of course! Her mouth twisted with exasperation at her hysteria. The sounds could not have come from within the house. They must, then, have come from the porch outside those windows across the sitting room.

Edith's eyes narrowed. The black blinds lay close against the sashes, and no light seeped in. The prowler could not possibly see her. But perhaps he was listening.

"All right, Dad," she said aloud. "I'll get you some fresh water from the kitchen." She walked deliberately to the end of the couch, to the door in the wall behind it. Her heels clicked on wood where the carpet ended. She opened the door, let it slam shut.

Then she whirled to dart silently to a window. Her fingers closed on the edge of its shade. Slowly, cautiously, she lifted it an inch away from the pane, peered out, the gun ready in her hand.

After the gloom of the house the glare hurt her eyes. Edith blinked, could see more clearly though the dull pain remained. Her forefinger tightened on the trigger about which it was curled.

The porch was empty. There was no one on the shaggy lawn. But a branch moved, down there in the hemlock hedge, against the wind!

The girl thought she could make out a deeper shadow low in the shadow of the hedge, as though something crouched there within the foliage. She pulled the shade a little wider, held it open with her shoulder, tugged at the window. She was going to lift her gun and shoot into the hemlocks. That was how far she had come already along the road of terror. She was going to kill the one who was watching Jeremiah Horne's agony, who was waiting for him to die.

The sash didn't budge. The girl glanced up, searching with her burning eyes for the reason. She found it. The window was nailed shut!

That, more than all that had gone before, pounded into Edith's brain realization of her father's situation. They had left him here, his friends, his neighbors of Welcome Valley, to die. To keep, sick as he was, a solitary, sleepless vigil against some furtive, inimical skulker.

Something else beat against her mind, something she had glimpsed in the kitchen as she had opened its door. In her anxiety to get to the window and trap the prowler, it had not penetrated, but now she remembered it, and it was an added horror to those that closed in on her.

The food shelves on the rear wall of the kitchen had been empty; Absolutely empty. There was nothing to eat in the house, except that one piece of dried beef on which Dad had gnawed!

Why had they left him like this? It was not like them. It was certainly not like Doc Rawlins. Perhaps he didn't know...

Edith let the shade drop again, glanced at the sleeping Jeremiah, ran out through a curtained doorway to the hall where the telephone was. She twirled the magneto handle viciously, snatched the receiver from its hook and jammed it against her ear.

"Number, please."

"Ring two-three." She knew her voice was husky, unrecognizable. She was glad of it. The operator was Martha Salant and if Martha knew who she was there would have been questions to answer. Even in school, she had been an insatiably curious little tyke.

The receiver clicked. Clicked again. That always happened when Doc Rawlins' number was rung. There was only one line through Welcome Valley, and everyone on it was lifting his receiver to listen in, anxious to know who was sick, what was the matter with them....

"Rawlins speaking. Who is it?"

"Edith Horne, Doctor. I—"

"Edith!" The physician's interjection was a shout of surprise. "Where are you?"

"Home. But listen—"

"How on earth did you get there? Didn't anyone see you?"

Those had been the first words out of her father's mouth too! What...?

"I just got here, Doctor. I found Dad—"

"I know," he broke in, as though he wanted to cut her short, as though he didn't want the eavedroppers to hear any more. "I'll be right over. If they'll let me get through again."

"If they—Who? Who would stop you? Why?"

"You'll find out." But that wasn't Dr. Rawlins' voice. Or was it Rawlin's voice changed, gruff suddenly, thick with threat?

"Doctor!" No answer. "Doctor." Had he hung up? "Doctor Rawlins, why don't you answer me?"

A laugh.... But it wasn't Dr. Rawlins who laughed. There was the same mocking, triumphant tone in that laugh as there had been in the one that had seemed to come out of the very walls of the old house.

"Who was that? Who was that laughing?"

No answer. Utterly no answer. Nothing but enigmatic clicks as the listeners cut off.

EDITH hung her own receiver up with nerveless fingers. Her

hand stayed on the cold rubber as though to keep her in touch

with reality. Her aching brow crinkled as she fought to get her

whirling thoughts into some kind of order.

First, both Dad and the old doctor had seemed astonished that she had gotten here at all. That meant that if she had been spied getting off the train she would have been stopped.

Second, her father had twice ordered her away, had ordered her not to let anyone know she had been here. Even in the agony he had suffered from the light, he had demanded to know whether he had touched her. The disease, whatever it was, must be terribly contagious....

That was it! The house was quarantined. No one had dared enter it, even to nurse Dad. That accounted for his being alone. It accounted for his surprising reception of her, and for the two men's surprise at her presence. But it did not account for the gun. It did not account for the unseen watcher, for the voice and the laugh on the 'phone.

Nor for Dr. Rawlins' doubt whether he would be permitted to visit his patient again....

Again! That meant he had already been here. That he had been treating Dad. But the old man was no better. The illness was beyond the country physician's skill. It was folly to expect him to know what to do for it. Edith had seen nothing like it in the hospital....

The hospital! If she could only get her father there. If only Harry could see him. Harry would know what to do. Harry....

What a fool she was! Harry was her lover. Midwest City was only a three hours' auto trip away....

Edith Horne was twirling the magneto handle again. "Martha," she gasped. "This is Edith. Get me long distance quickly. Midwest 4386. Hurry!"

"Edith," Martha's tone was queer, "I can't get you that number. I cannot take any out-of-town calls from your 'phone."

"You—you—" Edith Horne couldn't talk, couldn't force coherent words out of her clamped throat. "What? What did you say?"

"I am not permitted to connect you with any out-of-town number." The operator took refuge in the metallic, expressionless accents of her vocation. Then her voice broke. "Oh Edith. I'm sorry. Terribly—"

"Why? What's going on here? What...?"

"I can't tell you. I don't dare....

"Martha!" The fear she had sensed in the house wasn't confined to it. It reached out over the countryside. It was reflected in the sharp thinning of Martha Salant's voice, in its tremble.

"Listen to me, Martha. You must listen to me. My father's terribly ill. He's dying. I'm calling a doctor for him, a specialist who can save him if anyone in the world can. You can't be so cruel, nobody can be so cruel, as not to let me...."

"I'm not permitted to...."

"Stop!" The distracted girl clung to the box, her fingers opening, closing, opening on its wooden surface as though somehow they could mould it into compliance.

"Stop saying that like a parrot. Like a—a soulless machine. You aren't a machine. You're the little girl who sat alongside of me in school. You're Martha Salant and I'm Edith Horne and we grew up together. We used to share boy friends. We used to hide from the boys because we liked being alone together better than anything. You cried when I went away to train and you made me swear that I would never forget you. You can't do this to me. You can't, Martha! You've got to help me!"

"I—I can't...." the voice in the 'phone sobbed. "I can't refuse you. I'll take the chance. But I can't connect you direct. That would be noticed. Give me your message and I'll repeat it to your doctor." There was terror in that voice, but now there was courage too. Edith was soon to learn how great a courage. "Hurry."

"God bless you! Listen. Midwest 4386 is Dr. Harold Gorton. Ask for him in person. Tell him Edith, his Edith, needs him desperately. Tell him to drive here and to bring both his bags, surgical and medical. Tell him to come quickly."

"I've got it, Edith. I'll watch my chance to make the call."

"Call me back and tell me as soon as you have. I...."

The line was dead. Martha had gasped, just before it went dead, as though she had seen someone coming. But she would do what she promised. Edith knew her, and she knew she could rely on that.

THERE was nothing to do now but wait for Martha's call

back that the message had been delivered. Nothing to do but wait,

and wonder why the quarantine extended even to the telephone; to

cower under the pall of dread that weltered in the darkened house

and wondered what Jeremiah Horne had done to deserve the curse

that had been laid upon him....

Nothing to do! Edith shook her head, abruptly. Why, there was everything to do. Her father lay in those frowsy blankets, the dirt of weeks caked on him. She was a nurse, and she thought she had nothing to do!

She must clean him up, bathe him while he was still under the influence of the narcotic she had administered. First she would fetch clean sheets, clean blankets, from the closet in his room above.

The girl started for the stairs that rose out of the hall's obscurity, twisting from a landing and then going through the ceiling so that she could not see what was at their upper end. She went up slowly, while little, uncontrollable quivers ran through her. She was tired, inexplicably tired, so that climbing these steps she was accustomed effortlessly to run up was a tremendous task. A dull ache throbbed, throbbed in her skull.

She reached the landing, turned. An oblong of light lay vertically against the wall above, angling in, Edith knew, from a skylight in the unwindowed upper hall. It was not very bright, but it stabbed her eyes with sudden pain.

She halted, shutting her lids against the discomfort. Apprehension twisted in her breast. Even though she had been in the dusk below for an hour or more, the light should not have had so great an effect. Could it be that she had become—infected? She pushed the grisly thought out of her mind, remembering the scare a pimple had given her a few days after she had tended her first scarlet fever case.

If she started to look for symptoms that she had caught her father's illness she'd soon get herself into a state where she'd be useless, unable to help him. And he needed her help so terribly.

She forced herself to open her eyes, to look directly at the radiant rectangle. Relief sighed from her lips. They didn't hurt any longer. She started up again.

A shadow flitted across the oblong of light! The same grotesquely contorted silhouette she had glimpsed on the ridge above Dark Pond!

ANGER exploded within Edith Horne, rage at all the inexplicable, menacing experiences the past hour had brought her. It took control of her, hurled her up the few remaining steps. Her heels thumped on the upper landing. She twisted....

The square hall was vacant! There was no one in it, and the dust on the uncarpeted floor was unmarked. The two doors giving on it were tightly closed.

Edith snatched at the knob of the one directly ahead of her, jerked it open. The hinges creaked with disuse, and the room behind it was empty as the hall had been. It was her own room. Nothing was disturbed. The little bed with its neat pink spread, the dresser, the washstand, were just as she had left it.

The other then. Her father's. Still in the grip of the wrath that had vanquished fear, the girl swung around, darted across the hall went into the slant-ceiled chamber where for years Jeremiah Horne had slept alone in the big, four-poster bed where she had been born.

This, too, was unoccupied. The mattress on the bed was naked. There were successive circles of dirt in the washbowl left by water that had dried. Dad's desk in the corner was cluttered with the papers and the small gadgets of his farm business, and over all lay a thick layer of dust. But no one was in it, there was no evidence of anyone's having been in it since he had dragged the clothing from the bed, and dragged himself downstairs to his long vigil with pain and terror.

No one in the hall, no one in the only two rooms up here! What then had made the shadow...? Had she really seen it? Had not her fevered imagination, wrought up by her father's condition, evoked the laugh and the footfall out of the creakings of the ancient timbers, the settling of the house's ancient stones? The shadow might have been that of a cloud, drifting between the sun and the hall skylight.

There wasn't anyone in the house. There couldn't be. The doors were locked, the windows nailed shut.... Was she sure? Perhaps Dad hadn't fastened those up here.

Edith got moving again. She reached the window, jerked up its blind. Yes. There were the nail-heads, the deep dents the hammer had made in the old wood of the sash. No one could have come in through this window or left by it. If there was anyone else in the house beside the Hornes, father and daughter, it was a bodiless phantom, a wraith to whose passage solid stone, solid wood, were no barrier.

The girl tried to shrug away that suggestion, but it remained, an unacknowledged chill tingled at the back of her brain of which she could not quite rid herself.

From up here she could see a small strip of the road beyond the hedge. She watched it for a minute, hoping that perhaps the nose of Dr. Rawlins' rattletrap coupé would poke into view, his premonition of trouble reaching here proven groundless. The longing for him, for any human companionship, rose bitter in her throat.

Quite suddenly all color drained out of the scene. A grey pall seethed along the road, making its soundless solitude more dreary still. Edith was momentarily startled, forgetting how quickly dusk was accustomed to take possession of Welcome Valley as the sun dipped below its western hill.

A figure appeared from around the curve where the highway passed out of sight to her left. It paced slowly toward the Horne house's gate. It was at first a vague wraith, its outlines indistinguishable. Then a vagrant light beam glinted on metal, and the girl discerned a long-barrelled rifle, slanted across a burly, mackinawed shoulder.

The pedestrian came nearer, moving with a strange, purposeful deliberation. The girl's forehead whitened against the pane and her eyes ached, straining to make him out.

HE was Jed Faston! Edith's breath whispered relief,

hissing past her white teeth. The unrealized apprehension that

had pent it faded. Jed was a classmate of hers. He lived down

near Wellton, his folks' homestead bordering on the Salants'

little farm whose white house served as the Valley's telephone

exchange. He was in fact, Martha's beau. He could not, then,

intend any harm to the Hornes. He was merely returning from a

rabbit hunt in the woods.

But he was walking too slowly for that. His booted feet thumped—right, left, right, left—as if he were a sentry on patrol.

A sense of other movement pulled Edith's gaze away from him. She peered to the right. Another form advanced along the road, from the direction of the village. This one, too, carried a gun across his shoulder, but he was taller, somehow gaunter than Faston. It was Uriah Scantell—the old grouch who had been the bugaboo of her childhood—his hatless white hair gleaming palely in the deepening dimness, his lank stature bowed under the weight of his toilsome years.

There was something ominous in the slow pacing of those two out there. Some dreadful quality of implacable determination. Of grim threat.

They met at the gate. Scantell said something to Jed, and the youth stiffened. Edith could see his face clearly now, and she saw a muscle twitch in its bronzed cheek, saw the openings between his eyelids narrow till they were tight slits. The blunt jaw hardened.

Jed whirled abruptly. His free hand fisted, lifting to shake at the house. His countenance was a marble mask of savage hate. He lurched at the gate, thrusting it open.

The revolver butt ground into Edith's palm. There was no mistaking the fellow's intention. Uriah had said something to the youth that was sending him to attack her father. To finish him! Her pistol jerked up. Jed wouldn't reach the house! Not if she still remembered how to shoot straight....

Scantell's bony fingers clutched Jed's arm, dragged him back into the road. The older man's fleshless lips moved, and the other's visage went quiveringly white. His hand went to his eyes in a gesture of horror.

That instinctive movement told the watching girl what argument Uriah had used to halt the youth's impetuous purpose. The plague that ravaged Jeremiah Horne was paradoxically his safeguard. They hated him, but they dared not come within reach of him to wreak their hate upon him.

Why? What had her father done to the people of Welcome Valley, that they should fling an armed cordon about him to keep him in, to keep help from reaching him until a more terrible death than any they could inflict should take him?

Scantell was speaking earnestly with Faston. Jed nodded, once, wheeled, retraced, stiff-legged the route of his sentry-go that was a relentless death watch.

Thud, thud, thud—Edith could almost hear the pound of his heavy soles as little jets of dust spurted from the road beneath them. They beat like blows of a padded hammer on her skull.

Uriah didn't move. He stood stiffly in the gathering gloom, watching Jed Faston march away from him. A furtive smile touched his bitter mouth. He had waited years, it seemed to say, for victory over his ancient enemy. Now it was his, full measure and running over. He it was, Edith gathered from the by-play she was witnessing, who had somehow inflamed the countryside against Jeremiah Horne. He was the inspiration of the grim patrol....

WHAT was he up to now? The youth out of sight around the

curve, Scantell had come abruptly to life. He whirled, dropped to

his knees, fumbled at something under the hedge. He lifted,

without his rifle, grasping a large brown, paper parcel.

He was through the gate, his long legs eating up the gravel bye-road that curved across the unkempt lawn. He reached the porch, went out of view under its slanting roof.

The old farmer was out again, before Edith could move, was hurtling back to the turnpike, his hands empty. He shot through the gate, scooped up his gun....

He was pacing back the way he had come, ramrod stiff, relentless seeming as before. Just as a rise in the hedge hid him, his head twisted and he looked straight up at the window through which the girl was peering.

Uriah Scantell was gone. He had known all the time that she was there. He had meant her to see what he had done.

What was it he had done? What had he so furtively dashed across the lawn to leave on the porch below?

Edith swung around. Bewilderment was a sick whirl in her head as she darted across the room, as she threw herself down the twisting stairs and through the almost total darkness that now invaded the lower floor. The revolver was in her right hand, but her left found the knob of the big entrance door by instinct, twisted it. The heavy portal swung open.

The bundle was on the threshold, right outside. Edith snatched it up, slammed the door shut again. The parcel felt bulky, irregular, as though it wrapped many smaller containers. Queer. She must see what they were, at once.

She switched on a light. Yellow glare from the fixture behind her jabbed her eyes with sudden pain, threw her shadow on the age-darkened oak panel she faced. Her vision cleared and the girl stared at the crinkled brown paper of the package she held.

She ripped an edge, tore a long triangle from it. Rounded glass of a mason jar gleamed through the aperture, serried ranks of preserved string-beans within it. Food! It was food Scantell had brought to her. But....

An edge of white paper rimmed the edge of the hole. Edith clamped her revolver in her armpit, tugged the paper out. A pencilled scrawl sprawled across the crumpled sheet. The girl read the words:

They'd kill me ef they knowed I was doing this, but I had to take the chance. I'll try and get Doc Rawlins through to you.

U. Scantell.

LAUGHTER twisted in Edith's breast.

Of all the people of Welcome Valley, of all Dad's neighbors, the only one who had any mercy, any bowels of compassion for him, was Uriah Scantell. Jeremiah Horne's only friend was the man he had hated for nearly two decades!

He was playing along with the others as the only way to help. A member of the quarantine patrol, he could sneak food in to them. He could permit Doctor Rawlins to pass....

But Rawlins couldn't do Dad any good. It was Harry.... Edith remembered Martha Scantell's promise to call back and report whether she had been able to reach Harry, realized that the time since that promise had been made was long, too long. Something must have gone wrong. She'd call Martha, find out....

Swinging around to carry out that intention, the girl was stricken abruptly rigid, all power of movement gone from her, a taut, quivering statue.

Where the telephone should be there was nothing but bare, white plaster, gashed where the bolts that had held the box had been torn out of the wall from which copper-ended wires curled, black tendrils like winter-blasted vines from a frost-riven trellis. The instrument itself lay on the floor, a mess of disjointed wood and wire and battery, utterly useless!

She was cut off now, completely cut off, from all human contact. But fraught with despair as that predicament was, it formed only an iota of the terror that greyed Edith Horne's face, that froze her blood, that wrung an unheard whimper from her pallid lips.

Here was proof indeed, devastating, nerve-shredding proof, that within the house, locked and barred against intrusion, an unseen prowler lurked. That telephone had been intact when she had gone upstairs. While she had been up there something had materialized to smash and destroy it, and had vanished again into the fearful limbo of nonexistence whence he had come.

A laugh, a footfall, the slither of fabric against a rough surface, a shadow—logic had explained these, denying that any enemy had won within the stone walls that made of the Horne house a fort. But this—logic, reason, could not deny. Material hands had done this thing, malevolent hands. The old house was no longer a fort. It was a jail, caging her in with terror.

The revolver thudded to the floor. Scantell's package slipped from Edith's numbed hands, struck her foot. She didn't feel the pain of it, but the fall split the bundle open. Jars, a loaf of bread spilled out, a roasted chicken. The girl stared at them dully. Old Uriah had dared much to fetch those here, but they would never be eaten. The fearful phantom was tired of waiting, he would strike....

"Edie!" A high-pitched cry shrilled from within the curtained sitting-room doorway. "Where are you, Edie?" There was the sound of a scuffle, of a vicious, animal snarling. "Edie! EDIE!" Terror-edged, the keen knife of her father's scream slashed the invisible bonds of eerie fear from Edith's limbs. She whirled around, flung herself through the portières into the room whence the agonized call had come.

THE complete darkness that flooded the great chamber was tempered by light seeping past the curtains from the hall. In the grey dimness Edith Horne was aware of a black bulk swaying above the sofa where she had left her father, a confused dark mass in the darkness.

As she neared it the murk revealed Jeremiah's ghastly face, his flailing, clawlike hands. And no one else! He was battling with something invisible, unseeable....

"Dad!" Edith screamed, seeing him thrown back, hard, on the sofa. She seemed to feel the blast of a cold wind blown past her, of an icy, impalpable presence that passed her and was gone. Then she had reached the couch, had thumped to her knees beside it, was gathering her father in her arms.

"Daddy dear," she husked, managing to get the words past the constriction with which nightmare terror clamped her throat "Daddy. What has happened? What—"

"Hush, baby," the cracked lips whispered. "Hush. Sleep, baby Edie. Sleep. Mother's gone away, but Daddy will take care of you. Always. Forever and ever." A gnarled and twisted talon reached out to stroke her hair, caressingly. "Sleep, baby Edie. Sleep."

The suppurated, lashless lids were tight shut, as Edith had last seen them, but from between their yellow granulations tears squeezed out to creep down the brown and scaly cheeks.

The chill of panic subsided a bit in the girl's bosom, and pity welled up within it, helpless grief. The wraith with which her father had been battling, she became aware, was real only in his own delirium. The effects of the drug she had administered were wearing off, but he was still under the injection's influence. He had been fighting a phantom of the long-dead years, was reliving now in his beclouded soul a scene out of the vanished past. The Edie for whom he had cried out was not his daughter but his lost wife, whose name she bore. Edith herself was the infant he thought himself fondling.

"Asleep," the agonized tones whispered. "Baby's asleep, but I can't sleep. Edie might come back while I'm asleep, and go away again because I won't be awake to tell her I forgive her. Tell her—" the mumble changed to the hushed drone of prayer—"tell her, God, that I forgive her. Tell her I will be here always, waiting for her return. Bring her back, God, when You think I have paid enough in suffering for the happiness You gave me and now have taken from me."

In his delirium Jeremiah Horne was lifting the veil from the secret he had hidden from his daughter for eighteen years. She knew now that her mother had not died then, might even still be alive. She knew why her father had always prayed, in the moments of her greatest joy, that The Lord should not ask too great a price of her in payment....

HER mother had gone away, and all these years her father

had been waiting for her return.

"Till the day I die, Edie, I shall wait right here, in the house I built for you...."

Edith was conscious of a feeling of shame, as though she were eavesdropping on the conversation of a soul with its Maker. She should not permit it.

"Father," she said firmly, though her lips were trembling. "Dad, dear. You must be quiet." Sometimes a cool, calm voice would penetrate a sufferer's fevered dreams and lull him into silence. "You must sleep. I'm right here, father, to watch over you."

"Watch...." The delirious babble caught at the word. "Where's my watch, Uriah?" She had succeeded only in jarring the wandering mind into another channel. "You promised to give it back to me as soon as you got back.... Lost it! Pay me? Man, what are you saying? There isn't money enough in the world to pay me for that watch. Didn't you read the words on the case? 'Edith to Jerry.' She gave it to me. She—And you want to pay me.... Damn you! Damn you to hell, Uriah Scantell. I'll—" He was struggling again, surging against his daughter's embrace "—never forgive—never...."

"Hush, Dad. Please hush," the girl pleaded, desperately. "You'll hurt yourself. You'll...." He was pathetically weak. She had once seen him throw Elmer Barnes, the hired man who was half his age, in a wrestling match, pinning the fellow down in sixty seconds, and now her own puny strength was more than enough to hold him.

"Friend," his struggles subsided, but his dreary monotone continued, rephrasing an ancient tragedy. "Wife. Both gone. Only little Edie left, only...." The voice trailed off into silence.

The trembling girl held the pitiful hulk of her father in her arms. At first she was aware only of sorrow for his long Gethsemane, then she was pondering the revelations of his delirium for some explanation of their present dreadful situation.

There was none. Even the notion that Uriah Scantell was somehow behind their predicament was effectually banished—if it had remained after his effort to aid them. The grudge that had lain between the two old neighbors was founded only in her father's grievance against Uriah. Scantell had none, could have none, against him.

It did not really matter. Nothing mattered, except that somehow she must keep Dad alive till Harry got here. Harry would save him....

She'd get the chicken, make a broth out of it. A hot broth would give Dad strength.... First she must have light in here. It was the darkness that was so horrible, pressing about her, hiding within it shadows that might be.... No. She mustn't let herself think of that either. Above all, not of the intangible, malignant presence within the house, that by all the rules of reason could not be there.

Light.... But light was agony to Dad. That was easy. She'd blindfold him.

Edith tore a strip from the hem of her slip, folded it across the yellow scars of her father's lids, knotted it behind his scabrous scalp. That done, she glided back to the entrance doorway, found the switch tumbler there, thumbed it up.

It clicked—and that was all. The chandelier in the ceiling did not flare, the brooding gloom remained. Something had gone wrong with the current in here—or had been made to go wrong! But there was still light in the hall. The girl pulled at the portières, pulling them wide to let that light come in.

Her hand tightened on the curtain edge. Out there, on the floor where she had dropped them, lay the jars of preserved vegetables, the roasted chicken. But the revolver was gone!

She remembered distinctly that container of beets rolling against it. Perhaps she was mistaken. Perhaps the gun was against the nearer wall, where she couldn't see it from in here.

It took effort to make the single step across the threshold. It took more will power, more sheer strength than all the hospital stairs Edith had had to climb in her three years of training. She managed it....

The revolver was not there. She was weaponless. Defenceless.

Suddenly she felt hands grab her from behind! She saw one on her arm, a gnarled, brown-scaled talon. The other was on her throat, clamping it, throttling her scream. Edith tried to twist, managed only to get her head around, to see a slavering, contorted mouth drawn away from yellow fangs, to see gory eyeballs, pupils shrunk to pinpoints, staring into her own dilated pupils. The effluvium of her father's dread disease was almost palpable.

The claws cutting off her breath tightened with infernal power, twisting her head back so that she could no longer see that horror-mask. Her lungs heaved, fighting for the breath that was denied them. The hall was a whirling, yellow luminance to her tortured sight. It was darkening, as strength seeped out of her.

Her water-weak legs buckled. The choking grip on her larynx was all that kept her from falling. Through the giddy dark mist that whirled around her, that whirled within her brain, she heard a cackling, mindless laugh, high and shrill and triumphant.

PAIN tore at Edith Horne's throat, tortured her eyeballs. A hand fumbled at the neck of her frock, loosening it to strip it from her.

She struck out, blindly, viciously. Her wrist slapped into a palm that closed on it, held it motionless.

"Easy," a voice said. "Easy there, Edie. You're all right. You're all right, I say."

The girl's eyes flew open, and she was staring up into the bearded countenance, the twinkling blue eyes, troubled but kindly, of old Doctor Hugh Rawlins!

"Easy does it," he said again, and she remembered that gruff, tender voice saying just that the day Doc Rawlins took her tonsils out. "I'm not going to hurt you. No one's going to hurt you."

The girl thrust herself up to a sitting posture, stared wildly about her. She was on the floor in the hall. She saw through into the sitting room, and her father was again on the sofa against the further wall, sleeping as though he had never left it.

Her gaze came back to the physician. "How—how did you get in here?" Had he seen that unnatural attack? "The door was locked." Pray that he had not. Pray silently that he had not.

"I have a key." It was still in his hand. "Your dad gave his to me when he first took sick, so that I could come and go as I pleased."

Rawlins had a key—he could come and go as he pleased.... But it wasn't he who had smashed the 'phone, who had tried to kill her. It was Dad....

"What happened to you? I came in and found you on the floor here, passed out."

"I—" She caught herself. She must not let the doctor know that it was her own father who had attacked her. It was the delirium that had made him do it. The fever. "I don't know. I—I must have fainted." Her hand went to her throat, to hide the marks which must be there. But Doc must already have seen them. He must be wondering how they got there. "It's—it's been so terrible, waiting for you, not knowing what to do for Dad."

"I know." His tired old voice, consoling. "It must have been a shock to you, finding Jeremiah as he is. I can understand what you have been feeling. I worried about it, all the time I was working over Martha Salant. I...."

"Over—Martha!" Edith exclaimed, catching hold of Rawlins' sleeve. "What do you mean? What's happened to Martha?"

"Never mind Martha." he evaded. "It's you—"

"Tell me!" The girl's cry was edged by hysteria. "Tell me. I've got to know. Don't you understand? I've got to know."

The doctor shrugged. "She's dead. Her throat cut. She was lying over the switchboard when they found her...."

"Her throat.... When? When did they find her—like that?"

"About fifteen minutes after you 'phoned me. She was still alive then, but she couldn't talk. I had a patient in the office and hadn't left yet, when...."

"Fifteen minutes. Fifteen—Maybe she got the call through. Maybe...."

"What call? What are you talking about?"

"I wanted to get Harry out here. Dr. Harold Gorton...."

"Of Midwest? The endocrine gland specialist...."

"Yes. Martha said she wasn't permitted to connect me but she would tell him herself. She...."

"That's it then! That's why!" Rawlins straightened, his bushy eyebrows beetling, the eyes beneath them stormy, suddenly with some obscure emotion. "By asking her to do that you condemned her to death!"

EDITH was somehow on her feet.

"Death! Doctor Rawlins...."

"They overheard you and they killed her trying to keep that call from getting through, just as they would have killed me if they'd caught me sneaking through the bushes to reach here. They...."

"Who?"

"All the men of Welcome Valley." Rawlins twisted, pushed out the light. Edith heard the front-door knob rattle, then it was open. Cool, sweet air came in. "Look, Edith," the old doctor grated. "Look out there."

A moonless night lay black over the countryside. But yellow sparks flickered, a far flung line of them, against the velvety blackness. They made a great arc midway up the hills, its horns swerving to the road, and the girl knew without being told that the circle of bonfires was completed behind the house.

"They're in the hills," Rawlins whispered, "all around, from where the turnpike from Midwest City comes over the gap in South Mountain to the depot in Wellton. I wondered why they'd called everyone out to do that, instead of just patrolling the road as they have been right along, and now I know. They're not going to let Gorton get through."

"Then, he's coming!"

"Yes, he's coming. But he won't get here." There was grim foreboding in that low voice in the dark. "Hiding in the bushes, waiting my chance to slip by, I overheard two of them talking. Now I understand what they meant."

"What did they say?"

"'Don't worry. He'll be stopped at South Mountain. If he argues, they'll know what to do.'"

"What?" the girl gulped. "What will they do?"

"They killed Martha Salant, didn't they? If Scantell didn't stop at that, he won't stop at another murder."

"Scantell!"

"He's their leader."

"But...." Edith's lips shut off what she had been about to say. A grisly suspicion was forming at the back of her brain.

"But what?"

"Nothing. Close the door, Doc, and let's go in to Dad. I don't care what happens to anyone else. You've got to help him. You've got to do something for him."

"I'll try again." The door slammed shut, and the light went on again. "But I've given up hope. His case is beyond me."

"Go on in and examine him. I want to pick up these things before they get spoiled." Edith bent to them, hiding her face from the physician's probing eyes. "Maybe you'll think of something."

He wouldn't, she thought, watching his feet move away from her, moving one after the other into the sitting room. He wouldn't even try. He had betrayed himself by that last remark, that Uriah Scantell was the leader of those who had drawn the ring of death around the Horne homestead.

Uriah had risked his life to bring this food here. He had been willing to risk his life again to pass Rawlins through the lines. He had not been called upon to do that.

Of course not. Because Doc had been already inside those lines. Doc had a key to the house. He, and only he, could have entered it to rob it of food. To smash the telephone. Before that—how easy for him, a physician, to do it, how difficult for anyone else—he had infected Jeremiah Horne with the illness that was destroying him. He had suggested the quarantine, had frightened the valley dwellers with his report of its awful infectiousness, till that quarantine was being kept up with almost insane fervor.

He had come in, just now, at the exact instant to save her from the sick man's attack. That was why he hadn't noted the weals at her neck, left by those choking talons. He hadn't wanted to question her too closely. He had been too anxious to get over to her his warning that any hope of outside aid was futile....

GOING through the doorway he had pulled the portières together behind him, but there was light shining from beneath them. He had known how to get light in there, because it had been he who had shut it off.

"Jeremiah!" That was his voice, inside. "Jeremiah, wake up."

He had probably given Dad an injection of atropine to counteract the morphine. "What," Edith heard her father mumbled thickly. "What.... who?"

"Hugh Rawlins, Jeremiah." Doc was speaking low, very low, but Edith could hear him because her ears were keener than most, and because she was straining to hear. "I've come back again to talk to you. To beg you to change your mind. Sign it. I've got it here." There was the crisp rustle of paper. "If you sign it they'll let me get a specialist from Midwest, and maybe he'll be able to save you. Sign it, Jeremiah."

"Never! I will never...."

That was it! A great light suddenly dawned on the girl. Rawlins wanted Dad to sign some paper. Till he did he would keep him alive. After that....

"You'd better, Jeremiah. If you don't you'll die here. Tomorrow or the day after. And after you're gone it will be Edith who will sign it."

"She won't. Before I die I'll tell her not to and...."

"That won't do any good, Jeremiah. Because they'll keep her here too, till she does."

"Why should they keep her here? She's not sick...."

"Yes she is," the low voice interrupted. "I saw her just now. Her eyes are bloodshot, Jeremiah, like yours were when this thing began. And there's a little spot of brown on the back of her hand."

He was lying! He must be lying. But the light did hurt her eyes. She had become so accustomed to that it had ceased to mean anything. Her hand....

Edith stared at the back of her left hand. There was a brown spot on it—a dark brown scale!

"EDIE!" The hollow, quivering agony of that half-scream from behind the portières, its infinite horror, might have come from the girl's own mouth that in actuality emitted only a rasping gasp more eloquent than any scream could have been. "Not like me! Not my baby!"

"Yes, Jeremiah." Rawlins' hateful voice was low-toned, inexorable. "She's got it, and I can't help her. Nobody can help her as long as we are trapped in here."

"All right. I—"

"No!" Wrath beyond reason ripped the monosyllable from Edith's throat. "Dad! No!" She rushed through the portières into the room, stood with hands imploringly outstretched to her blindfolded father who was sitting up on that sofa, a ghastly caricature of humanity. "Don't give in to that fiend."

Rawlins spun about to her, his bearded countenance that always had seemed so benevolent, so venerable, suddenly a false face of malignant fury; his eyes blazing hatred.

"Fiend! You don't know what you're talking about, Edith...."

"I know. You infected me just now, while I was unconscious. You infected Dad and came back to be in at his death, to put him in that...." Her arm jerked up, flinging a gesture at something which leaned against a wall. In the murk that till now had cloaked this room she had thought it only an angular shadow—"in that coffin!"

A shrill, mad laugh jittered from her contorted lips as she stared at the roughly-made casket. Crudely hacked together—Dad had made it himself. Alone, deserted, before all his strength was gone he had painfully hewn his own death-box in pitiful anxiety that his violated body should at least have decent burial.

"Ghoul," Edith shrieked at Rawlins. "Vampire!"

"You little fool!" He leaped at her, all pretence of benevolence gone, his bearded countenance distorted with fury. He towered above her, a hypodermic in his hand, its keen needle stabbed at her as he hurtled toward her.

Edith's own hand swung at him in purely instinctive desperation. A mason-jar she had not realized it still clutched flew from it, crashed square on Rawlins' forehead.

The doctor went down like a pole-axed steer.

The girl shuddered, gazing down at the fallen giant. She had done this....

Suddenly she found she was trembling no longer. She was oddly calm. "Dad." She turned to her father. "I—"

He didn't hear. He had fainted. The frenzy of excitement draining his fever-enfeebled constitution of its pathetically small strength, his monstrous body lay prone beneath the sheet. On the floor beside it there was a long, legal-looking document, lines of typewriting black across it.

Edith walked quite steadily to the couch, picked up the long foolscap.

Jeremiah Horne, hereinafter known as the party of the first part," she read, "agrees to sell to MOON PETROLEUM PRODUCTION COMPANY hereinafter known as.... right, title and interest.... land in Welcome Valley bounded...."

THE Moon Petroleum.... Recollection thumped behind the

girl's temples. She saw again the stagnant waters of Dark Pond,

the iridescence filming its surface. That was oil...! She was

beginning to understand. There was oil under the Horne homestead.

Producers had discovered it, had offered to buy the land. Dad had

refused to sell. He had sworn to remain here till he died,

waiting for his lost wife, and he would keep that oath in spite

of hell itself.

This contract to sell was what Rawlins was trying to force him to sign. But why should Rawlins....?

Wait! Development of the valley as an oil-producing center would rescue its land-poor denizens from their poverty. They owed the physician thousands upon thousands, debts accumulated through the decades he had served them. He had never expected to collect these, but if prosperity came to his patients he would be paid and at one stroke become independently wealthy. With hundreds of laborers coming in, that wealth would increase....

Jeremiah Horne's obduracy blocked all this. Rawlins had evolved a demoniac scheme to break it down, and with the utter depravity of a conscienceless man debauched by avarice, he had put it into effect.

He had poisoned the old farmer with some obscure and dreadful virus. Playing upon their fear of contagion, and their own frustrated hopes of fortune, he had inflamed Dad's neighbors to their puzzling, fierce hatred of him, so that they would go to any lengths to maintain the quarantine he had set up, even to the extent of what they regarded as legal murder.

And then she had walked blithely into the trap. His precautions set at naught, Rawlins had changed his tactics. He must force the signature from Jeremiah Horne before he died, or, failing that, must use the same diabolical means of persuasion on the daughter.

That was why he had spied on her. That was why he had killed Martha Salant, trying to prevent the message to Harold Gorton from going through, had smashed the telephone so that Edith wouldn't know it had gone through. He had waited until she reached just the right pitch of terror to make her amenable to his will, and had been forced to intervene to save her from her father's delirious attack, scaring him off by the rattle of the door-knob. While she had been unconscious—Edith stared at the sore on the back of her hand—he had infected her with the horror.

The soft lines of her face had hardened, until it was a lined, white mask utterly without emotion. Her mouth was no longer a rose-red curve made for kissing but a straight, grim, colorless line.

She pushed through the door to which she had stalked. It swung shut behind her. It fitted closely into its jamb, so that no light seeped through, and the darkness in here was absolute, but Edith did not pause. She went steadily into the murk, making for the back entrance to the house that had been bolted against her—was it only two hours ago?

She went through that door. She walked on into the night where the fires burned over which crouched men who would shoot her on sight, as they would a rabid dog. She was leaving the father she loved with an ardor magnified by pity for what he endured, alone with the man who had inflicted upon him that torture. It was the only way she could make certain of Dad's safety.

She might be killed. She was almost certain to be killed. Yet her death would save her father. For if the land went to the State it would be years before the oil company could negotiate for its possession.

She might be killed, but if she could get through to South Mountain, if she could intercept Harry Gorton where the patrols would stop him, she would tell them what she had learned and they would let them both through. Harry would know how to cure Dad and....

The touch of her groping hand on the door's painted surface interrupted her dreary thoughts. Edith's fingers slid down the boards, found the bolt. It rattled metallically. She shoved it out of its socket....

There was the pad of a slithering footfall behind her, a low, bestial snarl! A moving bulk, black against black, loomed before her. The overpowering fetor of the plague swamped her, and a horny something rasped her cheek. It fastened on her shoulder, and a laugh, toneless and horrible, beat at her ears.

The girl lashed out, extremity of terror lending her savage strength. Her little fists pounded on skin that was not skin but a scaly, repulsive integument. They jolted the attacker's grip loose from her shoulder, a long strip of her dress ripping loose with them.

Her assailant lurched back to the assault, snarling. She was involved in a maelstrom of combat, of battle invested with a strange primeval savagery, with a supernatural ferocity. Claws lacerated her, tore more and more of her frock from her until she felt she was almost naked. She fought back, fury whimpering in her throat, her own little hands clawed, her carefully manicured nails tearing flesh that was rotten somehow under its dry shell. She fought hopelessly, knowing she could not win, knowing that the unseen terror must overwhelm her at last.

What was it? What in God's name was it? Speculation vanished as the thing swarmed over her, as she tottered backward under a sudden access in the fury of its attack. A hand—she could feel that its fingers were stubby, mere rotted stumps—pressed against her breast, thrusting her against the door, crushing her flesh....

The fierce pain aroused the reflex of a final savage effort within her. Edith twisted away from it, her shoulder battering into the attacker, thrusting him away for an instant. She heard it squeal, scutter back.... But in the instant's respite her frenzied hand had found the doorknob, twisted and jerked it open. The wood thudded against her lurching antagonist, held him back for another split second as she scraped through the narrowing opening, sprawled headlong into the bush, sprang to her feet again and ran, breathlessly, agonizedly, through the night.

The door slammed again, behind her, and she knew that the mewling thing she had fought was out. She heard its scutter behind her. It was otherwise silent, and she was silent, fleeing between the circling lights that told of danger almost as terrible as that which pursued her.

They were men she could see clustered about those lights. But she could see their ready rifles too, and she knew that if she veered toward them they would shoot first and question afterwards. She could only keep going, straight ahead, along the long axis of the valley, hoping against hope that in the darkness she might lose her pursuer, might evade him.

The fleeing girl looked ahead again, picking her way through tangled bushes of some fallow land she had reached. The withes slashed savagely at her, cutting her, reminding her excruciatingly that she was half-naked, that her body was netted with lacerations, wet with her own blood. She splashed through a shallow brook, stubbed her toe against an unseen rock, sprawled on the further bank.

The fall knocked breath out of her. She tried to get up again. She could not. All her strength was gone. She could only lie here panting, gasping, tremors shaking her like an ague, while the thing she had out-distanced hunted her down.

EDITH could hear it, as the blood pounding in her ears subsided, rustling in the bushes, snuffling. A tiny hope grew in her as that sound grew no nearer, as finally it moved away.

The monster had lost her trail. She was safe, safe. She could lie here and recover her strength, and when morning came she would manage to let the quarantining villagers know, somehow, what she had found out. Dad would be safe till then. She would be safe.

The stars circled giddily. Edith turned her head to escape their vertiginous dance. They were cut off by the stygian shoulder of South Mountain, a jog in it the depression where the Midwest Turnpike came over the spur and down into the Welcome Valley.

And suddenly shining on that turnpike was a pair of automobile headlights!

A long finger of light shot upward, a spotlight reaching into the sky. It blinked. Once. It blinked four times, rapidly. A pause and the signal was repeated.

The signal! Harry's signal! He had taught it to her in the first days of their courtship so that she should know he was outside the hospital and would slip out to meet him without subjecting her to the catty gossip of the Nurse's Dormitory. One dot. Four dots. Radio code for E.H. That was Harry's car and he was signalling to her that he was coming. It was Harry...!

The oncoming headlights were abruptly motionless. A figure was revealed in their beams. A figure, and a rifle levelled at the unseen driver.

At Harry!

They had stopped him. But he would not let them stop him from her. He'd argue with them for awhile, and then he'd lose his temper and fight to get through. They'd shoot him!

EDITH hadn't realized how far she had run from the house, with the eerie thing pursuing her. There was only some two hundred yards between the brook and the pass, but that two hundred yards was all uphill, so that they seemed infinitely long to the desperate girl.

The struggle for air seared her laboring lungs, every step was a separate, terrible agony. At last, however, foliage was a dancing, leafy screen against headlight glare ahead of her, and Harry's angry voice pounded through to her.

"I'm not arguing with you any longer. If you don't know a quarantine doesn't apply to physicians I'm going ahead anyway. Get out of my way or I'll ride you down."

A starter whined, a motor roared into life—and a rifle bolt clicked.

"Stop," Edith screamed, catapulting out into the road. "Stop, Harry! Don't shoot. Don't."

"Edith!" Harry exclaimed. "Good Lord...."

"Edie Horne." Uriah Scantell swung to her. "You—"

"Uriah!" He was alone in front of the physician's sleek-nosed roadster. "You're going to let Dr. Gordon through. You've got to. Doc Rawlins is fooling you all. He poisoned Dad and made you help him in his terrible scheme."

"Whut's this?" The farmer's gaunt face was grey, hollow- cheeked above the rifle-stock that hugged his shoulder, and there was shock in his bleared, dark eyes. "Whut's this ye're sayin', Edie? Whut are yuh drivin' at?"

"What happened to you, Edie? You're torn to pieces. What....?"

Edith ignored her lover for the moment. "I've found out all about it. Listen, Uriah."

The story, as she had reconstructed it, spilled from her in a spate of tumbling words. "You aren't going to let him get away with it, are you, Uriah?" she finished. "You're going to help Dr. Gorton reach him and save him. I promise Dad will sell to the oil company afterward. I'll get him to, now that I know why he refuses."

"I didn't hold with whut they was doin'," Scantell replied, ponderingly. "But I didn't dare go again 'em. I don't dare naow. They won't believe yur story, though I do. S'posen we wait tull mornin' and I'll put it to 'em."

"It will be too late in the morning," Dr. Gorton said. "The girl who called me described Mr. Horne's symptoms. The sensitiveness to light, the hypertrophied joints and scabrous skin, are typical of an aggravated form of botulism, a fungous disease. I brought along the only cure for that, but the treatment must begin at once. Mr. Horne will be dead by morning, almost certainly. I'm surprised that he has lasted as long as he is."

Scantell's head swung around to him. "An' yuh kin save him if yuh git ter him now?"

"I'm quite sure I can."

The old man shrugged. "Guess I got ter take th' chanct then. Look here, yuh go 'cross these fields, th' way Edie come. The rest uh the watchers'll be expectin' me ter stop yuh, an' they won't be lookin' fer yuh ter be comin' that away."

"That's sense." Harry's lank, lithe figure swung out of the car, a physician's strapped black bag in his hand. "Tell me just how to go...."

"You can't go that way," Edith interrupted. "Not alone. There's something prowling the fields—something horrible. It almost caught me, almost killed me. You can't get by it unarmed."

"Something—what do you mean?"

"I don't know. All I know is that it did this to me. I caught one glimpse of it, and it looked like Dad looks, only more horrible. I can't understand...."

"I kin," Scantell broke in. "Thet's Elmer Barnes. He got th' same thing Jeremiah did, only he went crazy an' broke loose. We bin huntin' him daown, but we couldn't locate hide nor hair o' him by daylight. Whur he's been hidin's a mystery."

"In the house!" Edith exclaimed. "He found some hiding place in the walls and lay there all day, prowled the countryside at night. But never mind that now. He's out in those fields and he'll ambush Harry when he tries to get through."

"Give me your gun, mister," Gorton said. "Give me your rifle. I'll know what to do with it."

"No," Scantell shook his head. "I wun't give it ter yuh. But I'll go along uh yuh, and git yuh through."

"Come on," Edith exclaimed, impatiently. "Let's get started."

"We're getting started, but not you, my dear. You're staying right here in the car. There's another bag with salves and antiseptics, and you know how to use them. Take care of yourself."

"All right." A veil dropped over the girl's eyes, as she yielded. "Go ahead." She too was poisoned with the fungus of botulism, but she wasn't telling Harry that now. And there was something else she held back. "Be careful, my dear. Oh be careful."

"I will." Harry wheeled, went into the bushes. Scantell went after him. Edith listened to the rustle of their progress down the hillside, her hand to her naked breast, her head cocked to one side.

And then, quite suddenly, she slipped into the thicket. Her old skill at woodcraft came to her aid, and she became a pale wraith gliding almost soundlessly through the lush tangle, following the two who went steadily onward, unaware of her.

The girl could not have logically explained why she did that. She knew only that some inner tingle of peril had warned her not to let her sweetheart out of her sight. A vague premonition that the night cloaked some hidden danger not yet revealed.

The couple ahead reached the bottom of the hill, went into the narrow clearing from which she had glimpsed the signalling spotlight. They paused, scrutinizing the black mass of shrubbery on the other side of the brook, and Edith halted, hidden but close behind, watching.

"He might be in there," Scantell whispered. "Yuh go ahead an' I'll cover yuh from here whur I kin git free swing with my rifle."

"Good sense," Harry responded, and splashed into the stream. Edith's straining eyes imagined they saw the bushes thicken to one side of him. Was it a lurking form....?

Abruptly Scantell's gun swung. Its barrel stock metallically against Harry's temple. The physician slumped....

Edith screamed, darting out of her hiding place, launching in a long, frantic dive at the man who had reversed his gun now, was driving its butt down to crush her fallen lover's skull. Her hands flailed at Uriah's arm, jolted it so that the lethal blow missed. Then his elbow pounded her away from him. She went to her knees in the water.

The rifle arced around. "Edie," Scantell grunted, and the lethal weapon levelled to point-blank aim at her breast.

"This is better than I thought. I'll get rid uh you too, an'..."

Orange-red flare blasted into a sprawling, black something that leaped in front of her at that last instant. The thing yowled, pounded down on top of her. A warm fluid gushed over her. Blood!