RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

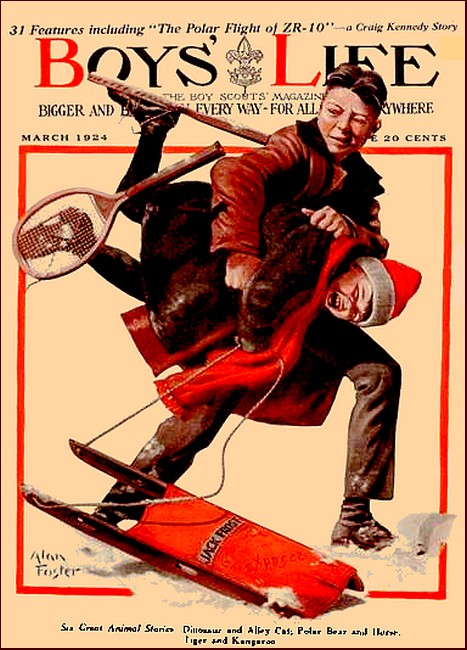

Boys' Life's, March 1924, with "The Polar Flight of ZR-10"

The Boy Scouts' Craig Kennedy, Harper & Brothers, 1925,

with "The Polar Flight of the ZR-10"

"YO!"

It was the great, full-throated voice of many men that sounded on the gentle air of the June dawn, sounded like one man, this call of the ground crew, two hundred and fifty of them, as their practiced hands guided the warping of the great ZR-10 out of hangar at Fieldhurst.

"People don't realize, Craig," I remarked as I contemplated the flight, "that if a straight line is drawn on the globe from Nome, or from Point Barrow, across the Pole, it will strike about Spitsbergen. Over the Pole is the shortest distance between London and Tokyo, five thousand miles against ten and, just half the distance the other way."

Kennedy nodded absently. "The thing I can't forget, Walter, is that the line passes through the heart of the blind spot of the earth—the unexplored Arctic, nearer Alaska than the Pole."

"Yo-o-o!"

The great silvered gas bag, or rather series of gas bags, was slowly beginning to poke her inquisitive nose further out of the gigantic doors.

Kennedy, formerly of the Office of Naval Intelligence, the famous O.N.I., had been requested to go along on the polar flight in the new ZR-10 to protect it against threatened sabotage from some traitor, some one believed to be in the pay of a rival foreign government. Perhaps this government feared it might lose something it hadn't yet got in the northland. Anyhow, it was on a warning that much was at stake in the flight.

I was along as an observer for a proposed semi-official Transpolar Air Service Company, Alaska to Norway and other countries. Our idea was to hop, say, from London to the southwest corner of Norway, along the coast to North Cape, then to Spitsbergen or Nova Zembla.* On the other side of the Pole, the service was to go two ways, one down the American side of the Pacific to Vancouver and Seattle, the other down the Asiatic side, with a short water jump to Japan.

[* Novaya Zemlya]

Kennedy nodded again. "Yes. Look at a map with the Pole as its center and the equator as its circumference. The Arctic Ocean is one of the smallest. The Arctic, between North America and Asia, is like the Mediterranean between Europe and Africa."

Though he did not seem to be doing anything much, Kennedy was watching acutely everyone we knew who was going on the voyage.

This crew was a happy bunch, care free. Besides, for facing the perils, did they not get plus fifty per cent of their pay for air service?

Suddenly I heard a familiar voice, of a boy, and a thick guttural of a man destined to become to me quite as familiar. It was Ken Adams, Craig's fourteen-year-old nephew.

"How did Ken get in?" I asked.

Kennedy shrugged. "How could you keep that boy out?"

You could tell Ken was up to no mischief. Ken's was an intelligent interest, the abounding curiosity, the love of romantic adventure, the wild desire to explore parts unknown that has carried grown men over all the earth through the ages. He hod been thrilled by this last lofty endeavor, this flight through the wild rushes of icy winds to the North Pole.

Over by the high fence that inclosed the field I had seen him many afternoons, sauntering up and down by the big gates, keen for a glimpse of the active preparations within whenever the gates were opened.

Men old in the service, trained and tried, had had a smile for the eager-eyed boy. They understood. Ken was dreaming dreams as they had done when they were boys.

Ken would salute respectfully as they entered. Some of the men used to stop to speak to him, too. One by one he got acquainted with them all.

Now I recognized the other voice. One of the crew of the ZR-10 had made fast strides in Ken's friendship. It was Erik Haakon, a Norwegian, roughened by life from his earliest years on the sea. Erik was rough in externals only. In character I believed him as pure as the ice of his own northland.

His views on things were as refreshing as the salt breezes he had known most of his life.

"Ken, you boy, you—what now?"

"I just came to say good-by, Erik, not yet but before you get off. Are you going inside? Oh, let me go with you. I'll not touch anything. Just let me look."

Erik had been sent on some commission, had executed it. Now he had just a moment for his young friend in this field crowded by everyone who could get a permit to be present to say good-by and witness the start.

Erik answered with a rough, kindly laugh as he tapped Ken good-naturedly on the shoulder. "A bird, boy—ain't she—a bird going north with the rest of them in the spring!"

Erik looked affectionately at the big airship as foot after foot of it came nosing out of the hangar. Ken seemed impatient not to miss anything. He did not even see us, so near.

"Oh, Erik, I'd love to be going. I'm crazy about it!"

There was a glint of humor in the eyes of Erik. "Whyn't ye write and ask 'em?"

"I did." Ken was reaching into his pocket for a much-read and rumpled letter. "Here's what I wrote."

Erik read it aloud to himself:

Fieldhurst, N.J., April 1.

Commander Hugh Scott, Fieldhurst Station, N.J.

Dear Sir:

I have been reading about the trip to the North Pole of the "ZR-10" and the continent of lost Vikings that, they expect to find somewhere in the unknown Arctic area. I would like to go on the trip with you. Can you take me? I am fourteen years old and in the Junior High School at Fieldhurst. I can get the consent of my parents whom you know.

Yours truly,

Craig Kennedy Adams.

Ken handed him the answer, read and re-read:

THE ARMY AND NAVY CLUB New York City

April 2.

Mr. Craig Kennedy Adams, Fieldhurst, N.J.

Dear Sir:

I have taken pleasure in adding your name and application to join the Naval Polar Expedition to the official list of candidates. As this list already contains several thousand names, it will be some time before the committee can make a decision.

Very truly yours,

Hugh Scott, Commander, U.S.N.

"Yah?" queried Erik, handing back the letters.

Ken looked at him wistfully. Erik was blond, big boned, with a certain amount of stolid dignity about him.

"And they didn't have room for me," replied Ken, dejected, adding, a moment later, "Erik, you must feel like the vikings themselves when they sailed the unknown seas and settled Greenland, discovered America, over a thousand years ago. Think what this airship might do! Suppose you should find some of your own people!"

"E-yah!"

Then I recalled scraps of conversations Ken had retailed, how Erik had told him of the old homeland he had loved and had repeated the legends of the brave and powerful vikings until they had enthralled the boy. I knew what was in Ken's mind.

"Mr. Jameson," he had asked me only a couple of nights before, after dinner, "did you ever hear of the 'lost vikings'?"

"I've read some of the sagas," I had replied, "the legends. There's an old story, also, that's a sort of classic, one of the seven original plots, I guess, the story of the 'frozen pirate,' in the ice, who came to life. A magician you admire made it into a picture, once. What do you mean, the 'lost vikings'?"

"Well, that's what, they call them. Only Erik says they didn't get lost. We lost them. You know about Erik the Red?"

"I've read about him," I admitted, without further admitting that I had read up for the purpose of my Transpolar mission. "Discovered Greenland in 985, then his son, Lief Erikson, came to the United States about 1002. As I recall it, Erik came back with tales of grassy fjords, sunshiny days, plenty of fish and game up there. Then his son found our country and named it Vineland."

Ken nodded. "Well, it wasn't long before those vikings up in Greenland had a prosperous colony and made what were fortunes to them in ivory and oil. Now, Haakon says, the account of the last ship from the colony to Norway told of its rich cargo. That was in 1410. But after that the plague broke out and wars swept Europe. Greenland was forgotten and the way to get there. It was the Dark Ages in Europe. Finally there were some Norsemen under Hans Egede who established the modern settlement there in 1721. The vikings of three hundred years before had disappeared. There were over ten thousand of them, in 1410 and in 1721 not a viking remained. They found the stone ruins of their houses. They're there yet."

"All dead; no children," I agreed.

"No!" asserted Ken vehemently.

"Then where did they go?"

"That's the viking mystery. Nobody knows."

"Maybe they went to sea and were lost."

"They couldn't. They didn't have any ships."

"Maybe they built some."

"There weren't any trees."

"Then," I strove desperately, amazed at Ken's information, "maybe the Eskimos killed them."

"No, no, Mr. Jameson," he replied impatiently. "The Eskimos are a gentle people. They wouldn't kill anybody. But, listen. They told a tale of white men going north, suddenly, to a land the Eskimos were afraid to go to. They feared evil spirits. They said the land was warm, that hunters found the fat caribou and musk ox. It was green all the year round. They even tried to tell of the route the white men took, in the direction of what the explorers now call the coastal trail route, north. Erik told me all about it. Think of maybe finding the descendants of these people, Mr. Jameson, to be the first from the outside world to reach them!"

I remembered how Ken had looked off into the night sky, the light of inspiration, of resolve in his big blue eyes. I remembered it and thought what a man among men that boy would be.

Jones, another member of the crew, passed and nodded to Ken. Jones, among other things, had charge of parachutes. Then passed Tighe, the grim joker of the outfit, and Rothen.

They paused a moment. "Turned down, eh?—along with about fifty thousand others," remarked Rothen unfeelingly. "Hard luck!"

"Well!" exclaimed Tighe. "We're carrying a bag of letters to Santa Claus at the Pole—at a dollar a. letter! You don't suppose we're going to carry all the kids up to see him, too, do you?"

Ken was abashed, but said nothing. Erik was not for spending his leisure minutes in footless good-bys. He started toward the interior of the hangar for his next, orders. Something had slopped temporarily the nosing out of the big ZR-10.

"Now, Erik, may I go in, with you? I won't meddle. I'll keep out of the way."

Erik looked around, sharply, put his hand on the boy's shoulder, leaned over, talking earnestly to him, as if that very intimacy might be his password to this aerial holy of holies.

ZR-10 continued now slowly to nose out of her

kennel.

At last ZR-10, "Star of the Skies," was all out of the hangar, tugging at guy ropes while the ground crew ran about executing frantic orders to those holding her down. There was the hurry and bustle and excitement of final good-bys. Rope ladders dangled down from the cages. Men like monkeys were running along the crazily swaying footway from nose to rudder. Way up at the nose was one man. Another suddenly seemed to appear from nowhere at the stern. Everything was ready for an early, sunrise start. She had not even been moored to the mooring mast.

"All ready!"

We looked for Ken. In the crowd surging forward, even in spite of the guards of the ground crew, we could not find him when we wanted him. The Call was repeated. We had to miss saying good-by to Ken, although I knew that had been his excuse for getting in there. We could not wait to find him. Off at last!

We saw the cheering, shouting crowd grow smaller, fade into pygmies, then into the green of the earth, finally disappear utterly in the haze and distance.

Most striking to me was the feeling of stability and of the perfect control of the vast ship, thirty-seven tons, in spite of the light materials that entered into her construction. We were quickly getting accustomed to life in the air.

A faint haze softened the outlines of the city below as we approached New York.

To those in the city the distant drone of the ZR-10's motors must have given the call. Then above the Statue of Liberty they must have seen from downtown what looked through the haze for all the world like a gigantic silver cigar which grew in size until the great ship was revealed in its whole seven hundred feet, longer by some twenty feet than the ZR-10.

We made the turn around the Statue of Liberty, the six motors throttled down to less than half speed, an American flag snapping proudly at the stern. Then we swept off majestically across the State of New Jersey, our silver-tinted dirigible in the sunlight an object of beauty.

It was getting along after noon. In spite of cramped quarters we managed to have a ravenous appetite. We found that they were cooking over the exhaust of the engines. The chow was soup and bread, canned meats, hot coffee and fruit. A strange thing to me was that there was running water all over, piped from supply tanks.

As I talked with the men, I speculated on their motives. The commander was eager for the prestige a successful flight would bring to the navy. Some saw fortunes, rewards from lecture tours, or perhaps knowledge for investments. Kennedy was silently studying the men on the expedition, making friends with everybody, and all seemed to like him.

On we went, easily sailing. I gave myself up to the exhilaration of it.

Suddenly we were startled. Was that a boy's shrill cry of pain above the drone of the engines?

"Hey, stop that! Please! You don't have to try and kill a fellow! Say! I found the leak! Please!"

It was Ken's voice. Ken had been discovered—a stowaway!

"I'll throw you over—you little spy!"

It was Rothen's voice. Tighe had seen Ken first, way up in the passages within the outer skin of duralamin that covered the interior gas bags. Rothen had Ken by the collar and was shaking him.

Down the footway Commander Scott reached them. "What's this, Ken Adams? Why have you done this thing. I'll have to stop at the next station and leave you!"

Sternly the commander spoke, and Ken flushed. He pulled himself up, with a sidelong glance of fresh terror at Rothen and Tighe. Then he faced the commander and his shaking hand went up in salute.

Kennedy and I were silent. I could see that Craig was vexed at his young nephew, but thoroughly angry at Rothen.

"I didn't have to show myself until it would have been too late to put me off," cried Ken. "But I had to tell about that leak!" He leaned forward in his eagerness. Was that a tiny spark of humor in the steel eyes of Commander Scott?

Anderson spoke up. "The leak indicator shows a leak. We've been searching for it. We can't afford to lose helium gas at this rate."

"Show him where," nodded the commander.

Ken saluted and disappeared with Anderson.

"Ken has done wrong, Commander," put in Craig. "May I radio his mother?"

"In a moment," he nodded back.

There was a buzz above the deafening drone of the engines. Then some of the men gathered as Anderson and Ken came back.

"It's mighty fortunate the boy was there hiding and used his head," reported Anderson. "It was worse than I thought. We might have been delayed some time, sir. I patched it. On the first leg we can make the repairs permanent."

Ken came shamefacedly over to his uncle. "Well, anyhow, you and the others can go on! The leak's patched."

"Ken Adams, we stop at Dayton. I'll radio your folks." It was Commander Scott.

Pale now, but self-possessed, Ken straightened and saluted. He would take his orders like a good scout.

"Sir." It was Anderson. "The men back here—"

The commander looked at Anderson quietly, raised his hand for silence. He turned from the men to the boy. "Put him off? Not on your life! He came out of hiding voluntarily to tell us of a hole in the gas bag, helium escaping. No, sir, he is our mascot. I will ask Professor Kennedy to radio to your folks that you are safe, Ken, with us—and going on!"

Ken's face broke into a smile. There was something like a cheer from the men.

It was then that I caught a surreptitious wink of Haakon's blue eye in the covert direction of Ken.

"Wonderful, isn't it, Uncle Craig?" remarked Ken, enthusiastically, later. "Not like traveling on a train or in a car. No bumps or shocks."

SOMEWHAT more than three days were consumed in crossing the

United States.

Greeted by wild enthusiasm, we flew up the west coast from California to Seattle, then up into the pan-handle of Alaska, Sitka, Juneau, Mt. Wrangel, Mt. St. Elias, twenty miles wide of ice, huge walls of sapphire, now melting and falling into the sea with a noise of thunder, across the Alaska Mountains below us like a relief map, the Yukon River, with fields of brilliant red and yellow flowers in the valleys, until at last we were sailing over the Seward Peninsula, with its hemlock and spruce and large cot ton woods, to Nome.

At Nome, as at other places behind us, was a mast, a 170-foot mooring mast, as at Fieldhurst.

Now we waited until the changes were completed to extend the cruising radius of our "Star of the Skies" to double what it had been when she was built. Also the last finishing touches were to be put on the radio station, JAZ, and mooring mast at Point Barrow, which had been delayed by the weather up there.

Nome at least had what passed for hotels. There were stores and banks and this summer there were more than ten thousand people there. Here also were organized the dirigible unit and the airplane unit, with planes that could land on water, ice or land, in case of emergency relief necessary to reach us. The ZR-10 had an ordinary cruising radius of three to four thousand miles. Changes had increased that to nearly double.

What interested Ken was the sunshine all day and half or all the night in the Arctic, with the vegetation growing fast.

"Down in New Jersey," explained Anderson, "in daylight the gas in ZR-10 is heated. The ship rises. Therefore gas must be released to make it heavier, bring it down a bit. But then the precious gas is gone. At night when it gets cooler, the remaining gas contracts. Ballast must be thrown out to lighten the ship then, so it will rise. Up in the Arctic we'll be better off with our twenty-four-hour day, perpetual day. There is less contraction and expansion. It is ideal for flying."

It was here while we were waiting at Nome that Rothen and Tighe started playing practical jokes on Ken. I did not like either Tighe or Rothen and was determined to watch them.

Then, too, there were the dark Eskimos, shorter than the Indians, with coarse black hair, black eyes, high cheek bones, broad fiat noses. Two of them, Anvik and Anuk, were much in evidence.

Hanging about Nome, now, we heard much of the real purpose of the trip, of the supposed rich hidden continent up there in the over a million square miles unexplored. The more I heard of it, the more I wondered was there a traitor among us?

CAME at last the morning set for sailing.

"Where's Ken?" It was Commander Scott to me.

"Isn't he on board?" I shouted back in the same hustle and excitement that accompanied the start of each flight.

"No. Haakon, Anderson and Rothen have looked all over. They report they can't find him!" He turned away impatiently.

Just then Craig appeared, perspiring in a sheep-lined leather coat, his helmet in his hand. He had just heard.

"Confound Ken's insatiable curiosity!" I exclaimed. "He's always wandering off to see some natural or native wonder."

Kennedy was troubled. "But, Walter, this isn't like Ken. He was eager to start. The commander will wait an hour. We must find him."

We had the whole town of Nome upset searching for Ken, but without a trace.

"Come on," decided Craig, "to the villages!" The dogs gave defiant barks; children tumbled out of huts in joy at seeing strangers. The older ones were more quiet. I saw one surly-looking fellow standing by his hut. It was Anuk, though I did not know him. He started forward, hesitated, stopped.

"Speak English?" asked Craig. The man nodded. "See a boy, about so high?" He pointed at one down by the water. "White?"

The dark eyes looked at us shrewdly. "So big—so thick?" With dirty hands he emphasized his gutturals by indicating about Ken's height and slenderness. Craig nodded eagerly. "Him go Slippery Trail. Much gold!" His eyes glittered. "Show the way?"

Slowly Anuk's hand went to his pocket. He pulled out an old greasy pocketbook, a gift from some miner, opened if, held it open upside down. Nothing came out. It was significant.

"All right. I'll give money." Craig slipped a gold piece to him. "More, when you find him!"

The Eskimo started off on a run. "We followed on to where there were some old abandoned shafts."

Anuk stopped. "Hear?"

"Yes, we did hear. It was like a call for help. But we could see no one." Ahead was a shaft. Kennedy pushed ahead of Anuk. "I hear something!" Craig leaned over exultantly.

"That Anvik and an Indian lowered me down here!" came Ken's voice floating up the shaft. "I was saying good-by to some Eskimo kids. They carried me off."

"Are you all right?"

"Only bruised a little. They threw the rope after me. Can you catch it, if I throw it up? I have it coiled?"

Anuk was working for more money. He climbed down the shaft like a mountain creature, caught the rope. Then the three of us hauled up Ken easily, scratched and bleeding and almost numb.

"Was he the man brought you?" I nodded.

"No; Anvik and an Indian. Anuk is Eskimo."

Craig paid him more gold. Anuk was not averse to taking gold to undo what his companion Anvik had done for gold.

We pushed on back. But it was far over the hour. Craig was worried.

As we came, nearly two hours late, into Nome we could hear the whirr of the engines of ZR-10. Ken groaned. "I'm your Jonah!"

"Good work!"

Down, the street were Commander Scott, Haakon and Jones.

"Couldn't leave that boy back." As Scott spoke I realized that no one could live with a boy like Ken without that boy finding a place in his heart. "Kennedy, I thought something was up, somebody wanted to leave you behind. I almost fell in the trap, too!"

So it was that at the last minute of sailing we knew there was a traitor among us.

WE were off at last, nosing our way into the unknown up beyond

the tree line of the Arctic circle, over the tundras, vast green

marshy plains now, brown frozen plains until the winter snows

covered them with white. In the short Arctic summer they were

covered by peat moss or tundra in the low lands.

We had started with skies blue and air clear and sparkling. Five hours later we ran into a thick bank of Arctic fog. Try as we might by rising and modifying our course, we could not run out of it.

"Try the radio!" ordered Commander Scott.

"I'm not getting a thing," replied Anderson. "And of course I can't tell whether anybody is getting anything I'm sending. The direction finder won't work, either!"

We looked at each other nonplused. If we could not get JAZ, then we were indeed out of touch, lost.

"You know, they said that up here in the Arctic one wouldn't be able to penetrate the auroral band with the radio," said Ken.

"Macmillan disproved that last year," put in Craig.

"Still," explained Anderson, "it is difficult to get messages here, and I knew it would be. But not on account of the aurora. It is on account of the twenty-four-hour day. In winter darkness it is easier."

On we blundered, as near north as we could by dead reckoning, trying always to climb up over the huge fog banks, too.

I had all but given it up, decided to trust in luck alone, when at last the sun burst forth in dazzling beauty. We had been able to climb above the fogs, for it seemed that the fogs now were lower than they had been farther south. But we had been carried far out of our course. Where were we? Were we right?

SUDDENLY a voice, a powerful voice, sang out even above the

drowning drone of the motors. It was Erik.

"Look! Land!"

We strained our eyes. Sure enough, there was the Arctic paradise. We came down a bit. It was clear here.

Landing might be made on this mountainous continent with its glaciers, rivers of ice, and green valleys. But if anyone took a chance in one of Jones's parachutes, which were safe enough, how would he ever get back? And normally it took two hundred men to handle ZR-10 on a landing. We had tried submarines and motor trucks in handling her, with success. But submarines and motor trucks were thousands of miles away, now.

Commander Scott called for volunteers. Erik and Tighe stepped out immediately, even before the rest. Then we learned that they were going to attempt the use of a newly developed grappling iron, which was to be cast off by us, and fastened in the earth by them as we floated in over the shore retarded by a gigantic sea-anchor.

The air was remarkably quiet and the whole operation was carried out with the utmost success. There was ZR-10 riding safely fastened to the new continent!

In relays we all took turns on landing. Soon we were surrounded by these strange men who could not speak our language, nor could any of us speak theirs, even two of the crew who had wintered with the Eskimos. For these peaceable men were not Eskimos. They were blonds, and the Eskimos were dark. The nearest thing to them of which I had ever heard were Stefansson's blond Eskimos. But even they were vastly different.

One after another we took our turn at signs and gibberish. No one had any success like Erik. Slowly he repeated words. Then, of a sudden, he turned to us, his face glowing.

"They are—they must be the lost Vikings!"

Phonetically, as nearly as I could make out, the names of these two men we had first seen were Iliak and Akhinot. They were taller than the Eskimos. There was a contrast in their light hair with the coarse black of the Eskimo, eyes almost blue, regular noses. They wore fish skin garments now, instead of furs, although they gave us to understand they wore the furs in the winter. The fishskin had an added value in that in case of necessity you could cut it.

Word by word Haakon was establishing relationship, that is as near as one could when one's brothers had gone back thousands upon thousands of years to the Stone Age while you had progressed through the most wonderful thousand years of the human race.

We learned of fish, salmon in incredible numbers, whales, walrus, sea otter and fur seal; of fur-bearing land animals, polar bears and a bear like the peculiar Alaskan glacier or kodiak bear; of a white Arctic fox, and a light-gray wolf, basal stock of their sledge dogs.

It was amazing. Here we were among men who were as our very forebears had been, ages ago, in the days of the saber-tooth!

Ken was keenly interested. It was his first contact with true aborigines. For instance, there was a girl who sang and tried hard to please. She carried what proved to be a native drum. Ken knew a drum when he saw it.

"But, look! She's shaking it, instead of beating it!"

It was true, she played it like a tambourine, unlike the Eskimos. When Ken took the drum and with a couple of sticks started to play it, there was consternation. Was he going to ruin it? He sang "The Star-spangled Banner," beating time with his makeshift drumsticks. Hiak's guests were delighted. One of the women passed Ken a seal's flipper to eat, a delicacy in token of approval.

"Uncle Craig!" Ken was dragging Craig over to the fire. "See, the fireplace is built of black stones. They're red hot. I saw lots of them, washed round, where the river runs into the sea. But they're burning. Hiak's wife is burning stones!"

Suddenly Kennedy changed from an ethnologist studying the almost Runic songs to the geologist. "Ken, that's coal—anthracite!"

Excited, Ken dragged us to the creek where he had been hunting crabs and had seen the black stones and black earth.

Quickly Craig traced them to their source. There, outcropping, was a black bed of coal, standing out between the rocks above and below, six feet or more of it.

Iliak was ready with his gibberish. I gathered that over the mountains was coal that could be lighted, soft, bituminous coal. Yet here were these people, with millions of tons of coal, freezing in winter!

As we took a short cut back to our camp, Kennedy began sniffing. The air was filled with a peculiar smell. The very earth seemed greasy. A pool near by was coated with a steel-blue scum.

Iliak again, by signs, made us understand that they laid cloths on this ground and soaked the stuff up to use as a medicine, for what I took him to mean, in his pantomime, rheumatism and sore throats. He indicated that most of his people thought it injured the land and had gone elsewhere to live.

As he gestured Kennedy uttered just one word, "Oil!"

"Mr. Kennedy," called Commander Scott, "I will let you name this continent, whatever it is."

"Then I christen it Arctia—the land of surprises!"

Arctia it was to us, after that, too.

A FEW hours later where the earth looked a certain way to

Craig he had Haakon and another driving a pipe. Suddenly from,

the pipe came a rush of something slightly bluish, cold. Kennedy

gingerly extended a long burning brand. Instantly it lighted, a

long tongue of flame! It was natural gas from a cavern

underneath. In the long Arctic night I could imagine this flame

rising and lighting up the country for miles around, making a

scene weird, ghost-like, almost terrible.

I was amazed. Here was a region perhaps three times the size of Texas, another Alaska, as big as the whole United States east of the Mississippi, the whole area originally in 1783.

"Planting the American flag here may be an act of foresight for future generations," exclaimed Kennedy, "as great a patriotic feat as buying Alaska. We have solved the world's last geographic riddle!"

"And," I cried, "it makes possible the dream of a regular transpolar air route for mail from London to the Pacific coast and to Asia! That route must cross American territory!"

I had half expected an Arctic paradise, perhaps surrounded by volcanoes and hot springs that made it semitropical or even temperate. There were hot springs, just as in the Seward Peninsula, and in Iceland, half around the other side of the globe. But it was still far beyond the Polar circle. Kennedy was right—Arctia.

WITH its sunshine all day and night, the continent of Arctia

was a land of wild surprise, topsy-turvy land, here at the top of

the world, of which we had known so little.

For here some rivers ran uphill, ice sank, or it bent like rubber and flowed like liquid soap. The ocean was hot and these lost vikings bathed every night in it. Darkness was more agreeable than sunshine. Flowers bloomed. The wind blew vertically—up and down. And there was more food than people knew what to do with.

It sounded crazy, but it was true, with explanations. Glacial rivers they were that ran straight uphill. One great glacial sheet, perhaps a thousand miles long and ten thousand thick, had down its blue-white face in July thousands of rivulets in the ice sheets, the small streams joining in crevasses, growing into roaring torrents. Pressure from behind forced it actually uphill. Almost a geyser in some places spouted up from the body of ice.

Of course when there is a certain combination of temperature and barometric pressure, any lump of ice will sink like lead. Also, salt water freezes only when the temperature is down at ten or below, because of its salinity. But between ten and twenty it forms an almost gelatinous mass that bends unbelievably before it breaks. Another thing in this amazing Arctia land. Heated air from the equator comes down at the poles and travels back again. If the air-traveler flies high going north, low coming back south, he has, in the main, favorable winds all the way.

But before we left, having delayed every hour we dared, we found Arctia indeed a land of wild surprise—not always agreeable.

We were just about to be hauled up to the ZR-10 when Akhinot came among us again, this time with another native, Neila. To our consternation, by signs we made out that far over on the other side was a pile of rocks which had been set up by some men with beards who had come hi a boat the year before. They had planted a flag, a red flag! Commander Scott's gloom knew no bounds. Then, after all, we had been too late!

We could not stop another hour. It was imperative, if we were to obey our orders on schedule for our own safety, that we not even map more of Arctia that we had done. We must be on to the Pole—and back again, ere began to settle that terrible Arctic night, that might otherwise be the night of death for us.

So we cut loose the grappling iron, sailed with a bit of heavy feeling in our hearts.

ON to the Pole, at last!

Our feelings rose as observations showed, several hours later, that we were hovering right over it. Down there was the open sea, full of ice floes, gigantic floes. But it was the real top of the world!

As the crow flies, it was 1,287 miles from Point Barrow to the Pole. We had gone much over two thousand miles, however.

"And, do you realize, Mr. Jameson," cried Ken to me, "that this is the Fourth of July?"

Haakon was tossing over the Santa Claus letters in a big water-tight can specially constructed so that it would float. On it it bore a message to communicate with the Navy Department wherever on the earth the can should be carried by ocean currents and picked up. Most likely it would follow the line of drift of the Jeannette wreckage across the Pole, down the Greenland Sea, through Denmark Strait between Greenland and Iceland, and into the north Atlantic.

"Peary found no land," observed the commander. "He sounded through the ice to a depth of fifteen hundred fathoms without reaching bottom." Scott was shaking his head in disappointment even in spite of our glorious success. "So we are not first here, either. Peary was here, April 6, 1909. We're nothing more than tourists!"

He gave orders to circle the Polo, as near as we could calculate it.

Then we were off to complete the flight to Spitsbergen, Nova Zembla, and Franz-Josef Land.....

We were just heaving in sight of Spitsbergen when Commander Scott, solemn-faced, called Kennedy aside in one of the forward cages.

"Kennedy," he whispered, "it's happened!"

"What's happened?"

"Some one has been in my quarters, has stolen my personal report that I am making, the photographs and maps, all the observations in it that I made of the continent Arctia. It's missing—the whole thing!"

The Commander regarded Kennedy strangely a moment. "I don't like to say it, Kennedy," he went on under his breath, "but you know how I have been with Ken Adams? He's the only one I've given the freedom of my quarters. Do you suppose, not realizing the enormity of it, the kid's been—er—tampering with things—through curiosity?" he hesitated. "Besides, I don't know that. I like some of his bosom friends—a hundred per cent!"

Kennedy restrained an exclamation. All he said, after a moment, was: "We'll watch. Treat him just as you always have—and watch!"

THERE was coming a sudden change of the comparatively mild

temperature. The mercury was falling fast and low. Great banks of

clouds loomed ahead. We could not turn and flee, beat them. The

hurricane was upon us almost before we knew it.

At first the commander tried bucking it. But it was not many minutes when we knew that we were indeed in for it, that the best we might hope was to bend to the gigantic will and power of Nature and trust in God. We were scudding down across the Arctic Ocean, before we knew it, headed with the terrific gale, as near as we could make out, for the north Atlantic.

Kennedy had been keeping a watchful eye on Ken. "Uncle Craig," chattered Ken with the cold, as the water vapor of the clouds in which we were lost seemed to penetrate everything, "this is the first time I've felt actually afraid on the trip!"

Craig managed to get Ken down along the lower walk where we slept in hammocks and bunks. The wind whistled like an angry spirit through the cables. The cloud was impenetrable. Our oiled coats shone with the drops of moisture congealing on them.

On, on, with irresistible fury the hurricane drove us, relentlessly before it. It was as though Nature resented the presumption of man in prying into her hidden secrets. How small even this great airship seemed as it bucked a cloud more huge and dense even than the one we had just passed through, how fragile, how helpless!

It was hard to keep courage. It was like being in a motor-car at seventy an hour when the steering gear suddenly becomes useless. In those few split seconds one can do more thinking than at any other time in one's life. It was Ken who was imagining that.

Craig tried to laugh. But there was an intended seriousness in it. "Ken, just now the only one who can steer our wheel is God! We are in his hands!"

The commander was issuing orders in his most naval manner. Things were serious when he adopted that.

With sudden swoops we seemed to dart down, with a rapidity that invited disaster. Then we would right and, straining and creaking, fighting every foot of the way, the ZR-10 was forging ahead with the elements in such a battle as never before had been fought by her.

"Get Ken inside—and keep him inside!" ordered Commander Scott.

Craig nodded to him. He took the boy by the arm and, as well as he could, piloted him to the corner of the commander's quarters. "You know, Ken, this part of the ship is sacred—the records—everything!"

It was the gondola containing the captain's cabin and chart room.

Terrified, Ken sank in a heap in the darkness of the commander's own bunk, his face in his hands.

For a long time he lay there quietly. Then suddenly he seemed aware that some one, something, was there with him. What was it, up here in the air? Was it an evil spirit? He lay out straight and quiet, listening and watching in the noise of the engine and the elements, almost frantic with fear.

Again he heard that noise. It was some one! A sudden flash of lightning. There was a man in the room with him! He was at the commander's Ales and records! Always the orders had been absolute about them. Who was this man?

Ken squirmed a little closer. What was his horror to see the man, his back to him, with the precious log book, the treasure of the trip. He held it up, as if lie were hunting for certain pages. Suddenly his hand made a motion as if to tear them out.

It flashed through Ken's mind, "This is the spy Uncle Craig was to catch!"

Ken drew himself up, standing on the bunk-edge, clinging. He waited a moment for the careening of the ZR-10 to help him. Then with a leap he was on the man's back, kicking and pummeling him, and screaming for help. The log book dropped to the floor with its partly torn pages.

Craig had been on his way to see if Ken was all right. In the door he grappled with someone in the darkness of the crazily pitching airship. The man broke loose.

Another wild wallop of the wind, another dip into eternity. Wild-eyed, with black hair stringing about, his face, the traitor stood for a moment, trapped.

Kennedy reached for him. The man dodged, lost his balance. The dip of the ZR-10 carried him to the rail. He tried desperately to catch himself. But through it he went with a piercing oath. It was Jones!

Craig gathered Ken in his arms and forced him back into the commander's quarters where lay the log book safe, with its precious records and observations.

There was a quiet smile on Kennedy's face as Commander Scott stumbled in, clinging for his life in the gale. But he said not a word.

The commander appreciated Craig's silence better than a flood of words. He reached over and grasped Ken's hand. "My boy, forgive me—you're a brick!"

Ken looked at Craig. What did the C.O. mean? He had done nothing, nothing but his duty. Kennedy never spoke. The storm and the tragedy were speaking loudly enough.

ON westward and southward we scudded, over the heartless ocean

that had engulfed the faithless Jones in a deserved death, on

south of Iceland, Greenland, until, as the north wind abated its

fury, we saw that we were far above what must be Labrador.

How like blind fate it was! The sun had broken out. The clouds had been dissipated. The air was mild again. It was the height of gentle summer.

Up the valley of the St. Lawrence we picked our way, limping now, homeward bound. We had crossed the Pole first—had virtually also been first around the world in an airship, in a technical sense. But it was still the continent of Arctia that was on all our minds. Had we failed—come a year too late?

Craig had been looking through the scanty effects of Jones. There was the commander's report on the continent, the photographs. But among them Ken had found a paper written in a sort of cipher. It had interested Craig, who was trying to figure out Jones. Ho spent some hours trying to decipher it.

"Mr. Jameson," Ken had evidently been turning something over and over in his mind, At last he had to say it, let it come out. "What did the commander mean—when he said to me—'My boy, forgive me—you're a brick?' I—"

I shook my head, interrupting. "Oh, nothing..... Just that you want to be careful with whom you make friends. What is it, Craig? Have you found the key?"

"Yes! Listen. Find the natives Akhinot and Neila. They will swear to the story of our people the year before on the other coast. I bribed them with my watch and some trinkets."

Ken almost danced as Craig decoded it. "Then, Uncle Craig, it was all a fake, that story, a fake by this Jones—Juane, you say his real name was—the red Bolshevist? We did discover Arctia! It does belong to our country! Hoo-ray!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.