RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Cosmopolitan, November 1917, with "The Phantom Parasite"

We turned. A young man who had been scanning eagerly the faces

of the

guests in the lobby of the hotel had caught sight of us and had approached.

Craig Kennedy is now back in his own country, having hastened his return on receipt of the news of our entrance into the European war, in the belief that his exceptional services would be needed in investigating conspiracies and plots that would naturally arise. A matter that is extraordinarily mystifying is immediately brought to his attention. Does it indicate treason? Read and see what he finds.

"TWICE I shot at the weird figure in the wheat-field. I hit it, too, for I am a pretty good shot. But it went on—escaped—and not a trace of blood left behind!"

Janice Bentley was very much excited as she handed Kennedy two peculiarly distorted bullets.

He and I had landed at New Orleans from Panama, on our way home from South America, and we had stopped at Washington to see whether our services might be needed by the government in the crisis. At the hotel, we had hardly registered when a very eager young lady met us near the desk. She introduced herself as Janice Bentley, and drew us over to a corner in the lobby, where it was quiet.

Janice Bentley, I recalled, was the daughter of a very wealthy banker of New York who had retired and lately had devoted himself to public affairs. Janice herself had repeatedly attracted attention in the newspapers by her advanced ideas, but, as I looked at her, I saw that there was really nothing unfeminine about her. Her activities were just the ebullition of youth in the finest type of young American womanhood.

"I'm so glad you are back, Professor Kennedy," she hurried on impulsively. "I have already employed a detective, Ronald Ravenal, from New York. But, so far, he has not been able to discover a thing. It's not a detective I need so much, after all, as a scientist. You see, when the war broke out, I realized what an important problem food and the crops would be. I've studied at an agricultural school, and for a year, too, I was here in Washington in the laboratory of the Department of Agriculture.

"I wanted to do my bit. So at once I gathered a group of girls, and we formed the Women's War-Gardens League. Perhaps you know that my father has a big estate at Bernardsville, New Jersey. It hasn't been under cultivation for years, but I easily persuaded him to let me have it plowed and planted. But my idea was something much more than a mere demonstration-farm, where women could show what they could do to feed the nation. That was merely a beginning. It was not long before I had extended the league work all over the country.

"We have one of the farms about twenty miles outside of this city, in Maryland, in charge of a friend of mine, Miriam Hess, where we have employed the soil expert, Professor Holst. There are scores of such farms now all over the country. My little venture has taken on very well.

"Now for the story: Early in the summer, I began to hear reports—vague rumors—that farmers were having trouble with their crops. Some said that fields had been trampled down by a mysterious night-rider.

"I determined to watch, myself. Night after night, I spent fruitlessly watching, for there did not seem to be any way of getting at the truth of the reports. At last, one night, on our own farm at Bernardsville, I was rewarded. I saw something moving in a wheat field.

"I called at the figure, but it did not stop. You see, I was absolutely fearless—then. As I advanced on it, I saw that it was going to get away. I fired. It got away. When I made search of the spot, I found those bullets."

In spite of the fascination of the simple narrative, Kennedy had been about to express some doubt as to the accuracy of the young lady's aim, but the two misshapen pieces of metal seemed to forestall that objection.

"But the figure," he asked; "what was it like?"

"I can't describe it exactly. It was like a man—perhaps —only bulkier—with a peculiar, pointed head—and a stocky body. It seemed to have legs—and arms—and yet—could it have been a man? My father suggested that it might have been some animal I saw—some tough-hided beast. I know he was at first inclined to ridicule. He thought I might have been seeing things—until he learned that others, too, had seen it."

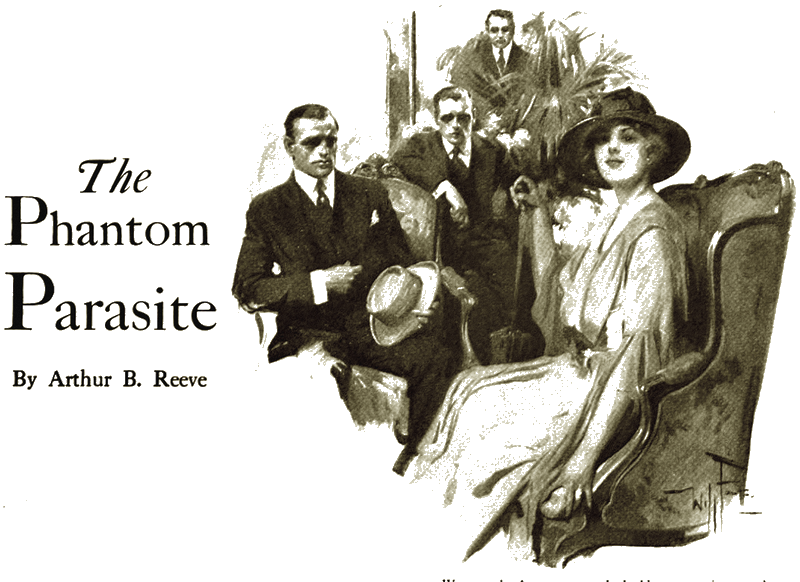

"I wouldn't talk too loud, Janice," interrupted a voice behind us. "It seems quiet enough here—but you never can tell."

We turned. A young man who had been scanning eagerly the faces of the guests in the lobby of the hotel had caught sight of us and had approached.

"I've been looking all over for you," he went on, in a pleasant voice. "Your father told me you were here. I had a few minutes before the railroad board meets."

"Oh, Clive," she greeted, "isn't it fine! Professor Kennedy has come back, and I am sure I can persuade him to help us. Professor Kennedy and Mr. Jameson, I want you to meet Mr. Fanning."

Clive Fanning was a tall young man in the early thirties, who had the general appearance of having been bred and educated among the more serious wealthy set. We all shook hands and, for a moment, glanced about, heeding his warning but seeing no reason for greater precaution yet.

"I was working on one of my father's railroads when the war broke," Fanning remarked apologetically, looking from his plain civilian clothes at the khaki and leather puttees of some officers not far off. "I volunteered, but was not accepted for the line. Instead, I was assigned to the engineers and set to work at railroading again."

"You must admit, Clive, you are more valuable at that," put in Janice. "You see, Clive is part of the great staff to handle shipments of crops to the seaboard. Often he fumes at not being sent over to the trenches. But don't you think yourself, Professor Kennedy, he is more valuable with his knowledge just where he is?"

"Undoubtedly," agreed Kennedy.

"I've been naturally greatly interested in what Janice is doing," Fanning remarked, as though argument on his own case was hopeless. Then he added confidentially: "It may interest you to know that we in the railroad service are just beginning to get reports of crop-deterioration in New England and New York. Now they are coming from New Jersey."

"Don't you see?" interposed Janice anxiously. "Just a few weeks after my own experience there, with this figure and the shots I fired, begin to come the reports. I am sure that there must be some connection. Always the crop-deterioration reports have come after appearances of this mysterious figure.

"I am not the only one who has seen it. Sometimes the farmers discover that it is only the fields that are trampled. But others have seen it and described it as I have—something of an outlandish nature, horrible. The same reports have just come in from Pennsylvania, too."

Kennedy was listening gravely.

"I'd like to talk to Ravenal—see how far he has gone already," he remarked, pocketing the distorted bullets.

As we rose, Fanning seemed to be disappointed, in spite of his urging to follow the case. It was easy to see that it was Janice in whom he was interested even more than the mystery.

"I'm sorry," he said reluctantly, "but I have an appointment at three with a railroad subcommittee on national defense. I wish I could go with you. I wish I could help."

"You can help," encouraged Kennedy. "Keep in touch with the news. You are in a splendid position to do that, much better than anyone else we could find. Anything may prove to be a clue."

QUICKLY Janice whisked us in her car to the office on G Street

which Ravenal was using temporarily while he was in the

capital.

Ravenal proved to be an intelligent young man, much above the average type of private detective. Miss Bentley was very diplomatic about our introduction into the case. She did not give Ravenal to understand that he had been superseded, but rather that he was still to have a free hand to pursue any investigations that he was making. Still, I could not help reading between the lines—or, at least, fancying that I did —some tinge of professional jealousy toward Kennedy. However, as Craig pursued his questioning with a tact only rivaled by Miss Bentley's, I saw that he was disarming Ravenal's suspicions, and felt that everything would be amicable between us so long as Ravenal desired it so.

"I must confess," remarked Ravenal, as the questioning proceeded and Kennedy elicited the paucity of facts that so far had been established, "that I find myself at a loss before this strange terror that confronts us. At first, I must admit that I thought it would be easy; but this is a great country, and when one is suspected in one locality, it is easy to move on to another. One thing I am convinced of: These reports are not a matter of chance. There is intelligence of the highest order behind it all, a malign intelligence without doubt, but one that it will do no good to underestimate."

"Are there any new reports?" asked Miss Bentley.

Ravenal nodded.

"Yes; I am sorry to say. I am beginning to hear from the South and the Middle West. Last night there came to me a report of something in the northern part of the state of Maryland."

Miss Bentley was all attention, and I thought of her mention of the war-farm not far from us.

"Have you seen the figure yourself?" inquired Craig.

"That's the strange part of it," Ravenal confessed. "Many reports and clues, yes. Yet the thing seems to keep just a jump ahead of me. Miss Bentley has told me much; others have corroborated and added to it. I think I have talked to nearly everyone who has had a glimpse of it. The stories seem all to agree pretty well. But when we go out looking for the figure, we don't find it. It is almost as if some one kept it informed of our movements. I watch in Pennsylvania; it appears in Maryland. I figure out where it is most likely to go next, and invariably it appears somewhere else. We seem always to be behind it. Sometimes I think—" Ravenal paused and hesitated.

"What is it?" urged Janice. "Do you suspect some one?"

"I'm not at all sure of some of our own citizens who protest their loyalty so loudly," he replied slowly and deliberately. "You cannot always disregard names. Blood is sometimes thicker than water."

Just what he was driving at I did not apprehend immediately. But Janice shot a quick look of surprise and inquiry at him. In his return glance, she read his meaning.

"You can't mean—Professor Holst?" she queried, startled.

Ravenal shrugged. Janice turned to us to explain. "You remember, I told you he was in charge of our Maryland farm where Miriam—Mimi—has taken a number of girls from Washington and Baltimore."

"Nothing has happened out there yet, of course," pursued Ravenal, "but that may be merely a blind to throw suspicion elsewhere."

"Oh, impossible!" laughed Janice, a bit nervously, though. "Oh, quite impossible! If you had told me that there was a romance on the Maryland farm, then I would have believed you, for I have seen it."

"Doctor Holst has been away a great deal," persisted Ravenal.

"Visiting, advising, superintending other farms," defended Janice.

"Ostensibly," replied the detective doggedly.

"I should like to meet Professor Holst," remarked Kennedy, "and Miss Hess, too."

"And I should like to drive you out there now," acquiesced Miss Bentley, as though eager to disprove Ravenal's theory at once. "Besides, I think it would give you an idea of what our work is like. The Maryland farm is one of our finest. You'll find Doctor Holst a most remarkable man. He was one of my instructors when I went to college. And Mimi—oh, charming! No, Mr. Ravenal; I'm afraid you are becoming unduly suspicious."

The young detective shook his head dubiously.

IT was late in the afternoon, but we were soon on our way over

a splendid road from the capital, Kennedy, Ravenal and myself,

while Miss Bentley drove. The ride was delightful, and when at

last we reached the farm, it was well worth a visit, aside from

our intense interest in the case before us.

In a sort of administration building, to which we went first, we were introduced at once to Doctor Victor Holst, the assistant professor of soil-culture in a Northern agricultural college, from which he had resigned to take up more practical work in the emergency.

Holst was indeed a remarkable chap, a rather rugged, athletic sort of pedant. Kennedy at once engaged him in conversation, and they were talking earnestly while Miss Bentley excused herself and went outside. A few moments later she returned, and with her was a young lady in a khaki suit. She was browned by the sun almost to the color of her suit. I knew at once that it must be Miriam Hess.

Mimi, as Janice called her intimately, was undeniably pretty, and I felt that she knew it. Even in her farming-suit, among this group of society- and working-girls on the farm, she was most stunning.

Introductions over, I could not help noticing that she and Ravenal were chatting with animation. Holst seemed to be watching them closely. Why had she singled out Ravenal? Was she trying to ferret something from him, hoping to fascinate him first?

A moment later, she transferred her attentions to Craig. Ravenal's turn it was now to watch, and it was evident that he did not relish Kennedy's coming into the case. Holst seemed equally keen, watching her as she talked with Kennedy.

A moment later, she transferred her attentions to Craig.

Ravenal's turn it was now to watch, and it was evident

that he did not relish Kennedy's coming into the case.

We talked for some minutes about the strange events that had just occurred. Both Doctor Holst and Mimi seemed to be at a loss to explain them. It might have been a ruse, as Ravenal evidently thought it was. But to Janice, it was quite convincing the other way. Kennedy suspended judgment. Finally, we returned to the city. At our hotel, Craig made excuses for both of us.

"You'll let me know if you find anything?" asked Miss Bentley anxiously.

"Surely," agreed Craig, as she drove off with Ravenal.

"It seems to be something systematic," ruminated Kennedy, pausing in the lobby when we were alone. "Let us see: The latest report is from the northern part of the state. I think I shall hire a car and scout about to-night. Perhaps the next appearance will be down here."

IT was not difficult to pick up a swift speedster at a near-by

garage, and, this time alone, we retraced our ride of the

afternoon. It was dark when we arrived near the demonstration-farm. Kennedy had provided himself with a road-map, and we now

began an apparently aimless tour of the country. There seemed to

be no other way of doing it.

Nothing happened as the night wore on, and there were fewer and fewer headlights that passed us on the roads.

Once, however, a roadster loomed up and swept by. As our own lights played on it, I recognized two faces. Doctor Holst was at the wheel, and by his side was Mimi.

There was no use trying to trail them, for by the time we had turned, they were far out of sight. Besides, by the direction, they were headed for the farm, and might merely have been out for a ride.

Our driving-about brought us back again on the road which passed the demonstration-farm, and it seemed to me as though we must be going past it for the twentieth time that night, for it was now past midnight. It had been a matter of hours that we had been running continuously, and our engine was missing. Kennedy pulled up alongside the road and stopped. As he crawled out from under the wheel, I saw that we were opposite a waving field of grain. Kennedy walked round and lifted the hood, while I stood beside him.

Once he straightened up and was about to find out what there might be in the kit of tools in the car.

"Look!" he exclaimed, pointing out over the field. I followed the direction of his finger. There, in the field, I could just make out the indistinct outlines of a moving figure. It was a strange thing—inhuman, like nothing I had ever seen before. Its head was pointed, its body unwieldy.

We watched for several moments as it moved about in the grain.

"Shall we go after it?" I whispered.

"Just a second, Walter," cautioned Kennedy.

He seemed to be waiting to see whether the thing would come any closer to us, but it had evidently come as close as it intended, and was turning away. Quickly he jumped up and leaned over the car, turning the switch of the electric spot-light and flashing it full across the field.

"Halt!" he cried, as the beam of light revealed the uncanny monster.

There was no answer, but, instead, the figure turned and, with surprising agility, leaped out of the spot-light rays and began to dart, zigzagging, away. At the same instant, Kennedy fired, emptying his revolver after it. Together, we dashed forward.

Though we were unencumbered, it had too great a start on us, and by the time we came up to the trampled grain, it had crossed the field. We followed, but when we gained the road on the other side, it was gone. Pursuit now was useless.

We returned to the trampled part, and Kennedy began flashing about his pocket search-light over the grain.

"What was it?" I asked, breathlessly, "a beast?"

"Beasts do not leave traces like this."

"A phantom?"

"Shadows do not stop bullets."

All about were marks of the intruder. But, more important than that, was something which, on second examination, we found had been left as it made its escape. The figure had seemed to realize that a greater than Ravenal was now on the trail. For it had cast away in its flight a peculiar arrangement which Kennedy's keen eyes discovered a few feet from the line of its retreat. He bent over and picked it up. It was a small tank, with a short hose and nozzle—a sprayer. In the tank seemed to be a liquid of some kind.

We continued to look about, but there seemed to be nothing else left by it. There was nothing to do now but to return to the city, and we made our way back over the field to our speedster. As best we could, we drove back, with one cylinder missing.

DAWN was breaking as Kennedy carried the tank and the sprayer

up to his room in the hotel. He had with him still his precious

traveling laboratory that had stood him in such good stead in

South America. In spite of the hour, Craig set to work

immediately, while I dozed on a couch in the next room. The next

thing I knew, the telephone-bell was ringing. Through the door, I

could see Craig still at work, and took off the receiver to

answer the call.

In spite of the hour, Craig set to work immediately.

"Miss Bentley?" I answered, recognizing her voice. "Good-morning."

I must have been asleep some hours, for it was now bright daylight.

"Oh, Mr. Jameson," she blurted out nervously, "I have just heard from Doctor Holst at the farm! Some one—something has been there. A field is all trampled up."

"Yes," I replied; "we were there last night, Mr. Kennedy and I. We saw the figure—shot at it—but it got away."

She gasped with surprise. "Did anything else happen?" she asked, with genuine anxiety in her voice.

"Yes; we picked up a strange instrument there. Mr. Kennedy is studying it and analyzing its contents now."

For a moment, she seemed to be stunned. "Do you suppose—it could have been—something to forestall suspicion?" she finally managed to ask.

"I'm sure I can't say," I replied, following the drift of her newly-aroused suspicions.

"Don't disturb Professor Kennedy in his work," she said. "I shall be over to see you as soon as I can get there."

IT was not long before she arrived, greatly excited.

"Have you found anything yet?" she asked eagerly.

Kennedy looked up, tapping the standard of the microscope thoughtfully.

"Yes," he replied slowly; "I have found something. While the visible world has been pretty thoroughly explored, there is still the realm of the invisible which holds marvels never dreamed of in our philosophies."

He paused. Janice looked from one to the other of us. What did he mean?

"Look through the eyepiece," he indicated, pointing to the microscope.

Under the lens was a strange thing. It seemed to be a scaly little monster covered by retrorse plates or bristles, so that it was practically impossible for it to move in any other direction than forward. Near the head was a remarkably large and powerful spear that could be seen through the skin.

"Every movement of the body drives it in a more or less forthright way through the soil," explained Kennedy, as we stared at him. "Coming against the roots of a plant, its muscular movement pushes the head firmly against the surface of the root, so that that spear with which you see the mouth armed is thrust forward and acts from a well-supported base—that is, the friction of the surface of the body against the surrounding soil. It is an iota—one of the most predacious of nematodes."

"'Nematodes,'" I repeated. "I have a vague recollection that they are worms."

Kennedy smiled. "Yes; I suppose you might say so. Nematology is a new science that bids fair to take its place alongside of entomology. We shall have our wormologists as well as our bugologists, soon.

"Millions upon millions of nemas are all about us, enormous, uncountable numbers. A thimbleful of mud may have thousands in it. Nemas from a ten-acre lot, if arranged single file, would reach round the earth. There are fifty varieties alone that are found in man. Every glass of water percolates over millions of their bodies.

"They don't resemble any other organism closely, though they are more widely spread than almost any other. They bite, puncture, gnaw, suck, and dig as do insects, but with organs entirely different. They see, feel, taste, and smell, probably hear. If they have jaws, there are usually three instead of two, and they act radially, like the jaws of a lathe-chuck. They are armed with ferocious teeth, moved by powerful muscles, considering their size. Sometimes, as in this case, the mouth is armed with a sting or spear with which to puncture the tissues of the victim before sucking the vital fluids.

"Lately, the knowledge of parasitic species of nematodes which cause disease has been enlarged. The dreaded hookworm is a nema. So is the scourge of the tropics, the guinea-worm. Trichina, which infects pork and causes a serious sickness called trichinosis, is another nema."

There was a knock at the door, interrupting Kennedy, and Clive Fanning entered. He seemed to be almost beside himself with excitement.

"I have just had a talk with some of the officials of my board," he hastened. "Reports are now beginning to come into the department from all over the country. You remember, the weather in the spring and early summer was very bad, but not bad enough to warrant what we are now hearing. Whole crops are being ruined—not everywhere, but in spots—and it appears to be spreading.

"Besides, this morning they tell me that the Bureau of Animal Industry has found a strange condition among farm-animals. Bovine tuberculosis has never been more prevalent. There is almost an epidemic of hog-cholera in certain sections, to say nothing of the increase in trichinosis. Whole flocks of sheep are affected by disease, and there have been many cases of glanders among horses. It's terrible!"

As Fanning looked at Kennedy, Craig merely pointed at the microscope. Clive glanced through it, then looked up inquiringly.

"That is one of the things our phantom figure has been scattering about," remarked Kennedy, explaining briefly what he had already told us. "Perhaps there are—there must be other attacks."

Fanning could only stare at us. Kennedy by this time was pacing up and down the room. He paused in the middle of his walk.

"Don't you see?" he cried excitedly. "This fellow is using the new science of nematology. Parasitic nemas are responsible for millions of dollars' worth of crop-damage yearly.

"The mutilation of root-fibers is what is done by that nema which you see under the microscope. True, when the root is destroyed, the plant throws out another higher up on the same axis. But if the plant is constantly at the necessity of supplying new roots in place of those killed off it hurts the aerial crop." He gazed fixedly at us. "Now you come and tell me that reports of attacks on farm-animals as well as on crops are coming in—that the thing is wide-spread and growing. Do you realize," he added, "we are fighting one of the greatest scientific nations the world has ever produced? Here is a new and unheard-of attack by science made at our very vitals—food. This figure which we have seen is one, perhaps the head of a band of parasite-planters!"

We stood listening, aghast. It was literally a species of soil-sabotage. Back of it all was undoubtedly a band of renegades. Who were they? Who was the mysterious figure, this strange night-rider?

WE were contemplating how to move against the mysterious

attacker when the telephone-bell rang. It was Ravenal, who had

guessed that Janice might he with us. He called up to let us know

that Miriam Hess had been to see him about the traces found in

the field at the farm the night before.

"I don't understand Miriam," Janice remarked thoughtfully, as she hung up the receiver. "Mr. Ravenal says that she hinted broadly that perhaps the next attack after Maryland might be at a farm which we have in Delaware. What can it mean? Mimi seems at one time to be head over heels in love with Doctor Holst—and then at another I almost think she is as keenly interested in Mr. Ravenal. I can make nothing of it. I must see her. Can't you go out there with me, Clive?"

Fanning, who had managed to beg off for a day, was delighted. As for Kennedy, he said nothing about the incident of the night before and the roadster in which he had seen them together, and, a few moments later, Janice and Fanning departed.

IT was not until the middle of the afternoon that Fanning

returned to us alone, much perplexed.

"We saw Miss Hess and Doctor Holst," he reported, "but I can't say that we accomplished anything. I don't know what to make of it—except that I'd be willing to wager that that was a false clue that was set out for Ravenal in Delaware."

As he told briefly about their unsatisfactory visit, I felt that indeed it was suspicious for Miriam Hess. It seemed as if she were playing on us for some one's benefit. Could it be Holst? Or was it merely that she was an incurable little flirt and was never happy unless she had one or two men in tow?

"There is only one thing to do," considered Kennedy. "We know what we are looking for, though we don't know where to look for it. We must continue to watch."

"But where?" asked Fanning.

"The attacker has already been seen in various places in Maryland," Craig considered. "As for the Delaware idea, I believe you are right. He must know that people there will be on the lookout, too. The next logical step would be across the river in Virginia, somewhere in the northern part of the state."

"I've been thinking of that and talking it over with Miss Bentley," agreed Fanning quickly. "You know there is the station of the government itself—the great Arlington farm. Miss Bentley, Miss Hess, Doctor Holst, and the rest have been greatly interested in that. Perhaps that will be the place to watch."

"Good," accepted Kennedy. "The Arlington farm it is. To-night we watch together. Don't tell a soul."

Accordingly it was settled, and, for an hour or two, Kennedy excused himself and went out, while Fanning also departed to complete his arrangements for the night.

NOTHING happened during the remainder of the day, and it was

not until after dinner that Kennedy rejoined me at the hotel,

where Fanning was now already waiting with his own car all tuned

up for the trip. As three of us crowded into a seat scarcely

large enough for two, I felt something bulging in Kennedy's

pocket.

"A new gun that I succeeded in finding after looking all over the city," he explained.

Over the river and out into the country we went until, at last, we came to the district which we had decided to watch.

Our chief purpose was to watch the fields of the one big farm which we believed to be threatened and, for this purpose, we finally decided to take a position in the shadow of a bend in the road on a rising spot of ground. There we waited, with lights dimmed, our senses alert to catch any unwonted sound, each concentrating his attention in a different direction. Once the quiet of the night was broken by the purring of a motor on the road beside us, and a car shot past, containing only a single figure.

"Janice!" exclaimed Fanning, involuntarily. "It was her car. You see—she guessed it, too!"

The moon was just rising, and there was sufficient light to see the car as it wound along the road, now and then coming into the moonlight. Without a word, Fanning leaped at the wheel and we were off, following. Her car had turned off the road to another between two fields and had dipped over the brow of a hill as we came on behind. As we nosed our way over, too, I saw that some hundreds of yards ahead, she had stopped.

"Look!" exclaimed Kennedy.

In the field to the right was the very figure we had seen the night before!

Fanning shouted as he stepped on the gas and sent his car hurtling along for every inch of speed in it. As he cried out, I saw the reason. The weird figure was advancing menacingly toward Janice.

In the still night, I heard the crack of a pistol. Janice had fired. Her shot had no more effect than if it had been a pith ball. Still the figure came on, evidently oblivious of our approach. Another moment, and it would be upon her.

Just then, I felt Kennedy rise in the crazily-swaying car beside me, and I heard another report, this time from the peculiar gun of which he had spoken when we set out.

The figure stumbled, but did not fall as though wounded. Instead, it seemed to be groping wildly about in the field.

"What did you do?" I asked hoarsely, as Fanning jammed on the brakes and we leaped out and over the fence into the field.

"Bullets are no good against that bullet-proof cloth," panted Kennedy, running forward. "I used a new lachrymose bullet—benzyl bromide—chloracetone vapor—produces temporary blindness."

Squarely at it again, Kennedy discharged another tear-bullet. He was taking no chance.

This time the thing fell, and, as it fell, I saw that it was indeed clad in a steel-lined jacket with leg- and arm-guards while above was a triangular headpiece with slits for the eyes—a thing medieval except that it had been designed to resist shrapnel and even the high-velocity modern bullet.

Just then, from the opposite direction on the cross-road glared the lights of another car. Then, as it turned, I saw in it a man and a girl.

Fanning had not run with us, but had gone straight toward Janice Bentley.

"Mimi—Victor—then it was not you!" I heard her cry, as Fanning reached her and swung his arm about her. "Oh, I'm so glad—so happy. Tell me——"

"Victor and I have been spending every night lately in the roadster trying to get some trace of the thing," came back a voice, which I recognized as Mimi's.

"And you guessed, too, that the attack would be here?" inquired Fanning keenly. "I thought—Delaware—"

"Oh," laughed Mimi almost merrily. "I had my suspicions. That was why I said that."

They were all coming up now as Kennedy bent over and uncasqued the head of the prostrate figure before him.

We stared in amazement. It was Ravenal—renegade detective—who had taken advantage of Janice Bentley's commission to cover up his own treason.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.