RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Cosmopolitan, May 1917, with "The Panama Plot"

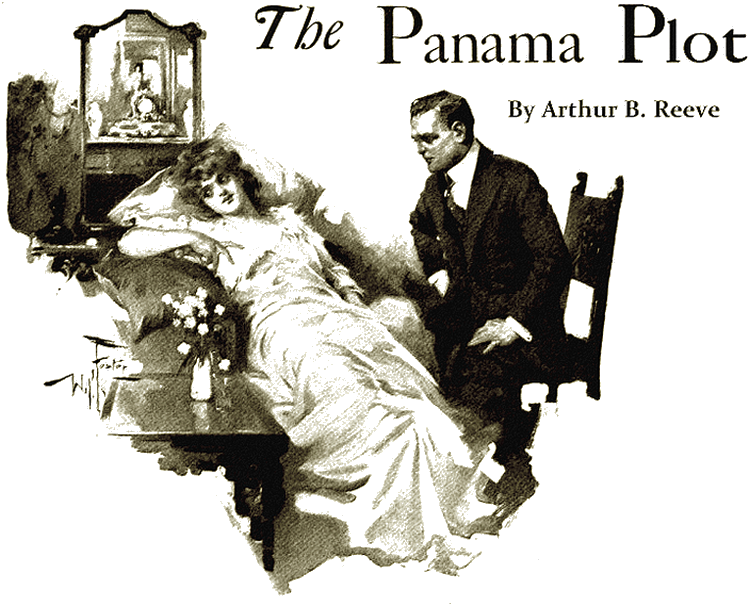

Craig bent over her soothingly, his eyes on the reddish spots on her fair skin.

The matter which brings Craig Kennedy to Panama upon Burke's request is one of vital concern to our country. It is safe to assume that no more patriotic duty confronts every true American to-day than that he shall add his voice to public clamor until Congress provides a scheme of defense for the Panama Canal that will make this most valuable and vulnerable artery the best-protected spot on the surface of the planet—absolutely safe from attack by land, sea, or air. The things that happen in this story and their certain consequences if the plot had not been frustrated are well within the limits of probability.

"THAT little moving-picture actress, Marcia Lamar, knows more about these new slides at Culebra than she's telling."

Burke leaned forward eagerly as he poured forth his suspicions to Kennedy in a secluded corner of the broad veranda of the hotel at Colon. On his way back to the States, after leaving us at St. Thomas, he had been intercepted at Havana and had been moved down to the Isthmus, like a chessman, by the chief of the secret service.

The first word that we had that Burke needed us again was while we were at Port of Spain, and came in the shape of a letter telling of a recent series of slides in the Culebra Cut which had aroused suspicion by their unwonted regularity. "Nothing is said officially," concluded Burke, in the letter, "but, just the same, the Zone police are hard at work. There have been some mysterious doings in this precious little republic. Come at once."

Glad of the opportunity, Craig had taken the next steamer to the Isthmus. At the dock, Burke met us, his impatience scarcely restrained even by the health officer, who took our temperatures, looked at our vaccinations, and, in general, made us feel as though we were trying to smuggle in a germ or two. The moment we were released, Burke anxiously hurried us straight to the hotel.

"What's the trouble?" demanded Kennedy. "What do you suspect? Is there anything new?"

"Yes; another slide last night at Cucaracha," plunged Burke directly into the subject. "For several nights, we've heard a peculiar buzzing at different points in the Canal Zone. It seems to be in the air. I think it's an aeroplane engine—some one flying at night."

Burke hitched his chair closer as Craig gazed thoughtfully out over the wide stretch of lawn under the file of coco-palms to the roaring surf beyond. "I suppose you don't know that, after Fowler's flight over the Isthmus three or four years ago, the President issued an executive order forbidding further flights. Well, no one is flying over the canal for any good reason. It would be the easiest thing in the world to drop a bomb almost anywhere. And the last time I heard the noise was the night of the big slide at the cut, as I told you."

He paused to give us a chance to absorb the novel idea of an attack from the air on the canal.

Just then, there was a commotion down at the other end of the porch. I could not see distinctly, but it seemed be a cavalcade of horses and wagons and an automobile. A motley crowd had piled out, all in the most outlandish of costumes apparently, many of them rough-looking fellows with dark faces, and gay bandanna handkerchiefs about their necks. I turned to Burke inquiringly.

"There's that moving-picture company now," he explained. "They've got special permission to come here to make a pirate-picture—nothing to do with the canal. Everybody here is crazy about Marcia Lamar."

I half rose, hoping to catch a glimpse of her.

"Calm yourself," restrained Burke, with a smile. "I'll introduce you to her later. Let me tell you what I've done," he went on, turning to Craig. "There are a lot of people here worth watching. Since pleasure-travel to Europe has been stopped by the war, more and more tourists are coming down to this part of the world.

"Well," he continued slowly, "I've been watching everybody. There's one group of tourists here that I've been interested in particularly, though. It's the usual combination of school-teachers, business-men, and people of leisure. But the most interesting to me is a young school-teacher from New York, Marilyn Marsh. Then, there's a man who seems to be in love with her—a fellow named Werner—"

"But what has that to do with Marcia Lamar—and this case?" interrupted Kennedy quickly.

"Just this: Marilyn Marsh is about as much like her in looks as one girl could be like another. The other night, one of the bell-boys handed her a message. It was meant for Marcia, but she gave it to me."

Burke drew out a piece of paper, handed it to us, and we read:

Marcia:

Important that I should go up to the estate immediately. More trouble over labor. Will arrange sites for later scenes of the picture.

Don't you think it is best not to announce our marriage until the picture is finished?

Love and a milliard of kisses.

Miguel Menocal.

"That was the night of the last slide," continued Burke, even before we had finished reading. "Menocal is a wealthy Panamanian who has been very much smitten by Marcia. The point's this: The company has already been up on his estate once, taking some scenes. Connelly—that's the director—has told me that one night he heard the sounds in the air up there. Besides, after the company made the trip, Marcia acted very strangely—seemed to feel that she was being watched and to resent it. I took Miss Marsh into my confidence then. And now I find that Marcia and Menocal are secretly married."

Burke paused at the sound of footsteps. We turned and saw a rather nervous and excited individual.

"Hello, Burke!" he greeted, with a glance at us which plainly indicated he was sorry not to find the secret-service man alone.

"It's all right; they're good friends of mine," assured Burke, introducing us. "This is Mr. Connelly, promoter and director of the enterprise which he calls the Caribbean Cinema Company— popularly, the C.C.C. How are things, Connelly?"

"About as bad as possible," the director returned, with less restraint than at first. "The whole picture is held up now. Marcia Lamar has suddenly been taken ill. Confound it, I don't know what's the matter with her. The doctor doesn't know; no one knows. Maybe it isn't a case for a doctor, anyhow," he concluded, with a quick look of appeal to Burke. Burke, in turn, wheeled toward Kennedy.

"I should like to see Miss Lamar," responded Kennedy promptly. "What seems to be the trouble with her?"

"Trouble? Trouble enough! Right in the middle of a scene, she was taken with a chill. We had to bring her back in the auto--"

THERE was a sudden crash of glass and splintering of wood not

twenty feet from where we were standing, as though something had

come hurtling through the roof of the porch.

"What's that?" exclaimed Connelly, jumping as if he had been struck. "Something through the roof?"

Burke had sprung forward.

"Here's one of the things!" he cried. "There are a dozen or more of them—went right through the floor—all but this one."

He handed Kennedy what looked like a queerly-shaped steel rod. It was about six inches long, pointed at one end, like a lead-pencil, but at the middle, instead of being cylindrical, it was fluted, milled out into four grooves running the rest of the length of the shaft.

Craig turned the thing over carefully, then dropped it. It fell true, sticking in the wooden floor upright, quivering.

"What do you suppose it is?" asked Connelly nervously.

"A flechette—a steel dart, used in Europe by aviators. A lot of them are placed in a large box and then released. No matter in what position they are let loose, they always land with the pointed end downward. The grooves make what is known as a 'feather-top.'"

I looked at Craig, aghast. Had some one aimed an attack at us, hoping, perhaps, to get us before we could set to work on the case?

"Whew!" whistled Connelly. "Say, one of those things would go right through a man if it hit him right. When it rains needles like that, if it weren't for Marcia Lamar, I'd go back to Kingston and finish the picture in Jamaica."

"I've had a couple of narrow escapes lately," remarked Burke, snapping his jaws. "There's something desperate going on—mark my words!"

"Let's move away from here, anyhow," suggested Connelly quickly.

"Might I see Miss Lamar now?" queried Kennedy, in a tone that indicated that he, too, felt the need of prompt action.

"Surely," responded the director, leading the way precipitately to the protection of the stronger roof of the main building.

WE found Marcia Lamar in one of the best suites in the hotel,

as befitted a motion-picture star with a fabulous weekly salary.

She was lying on a couch beside the window where there was the

most air, while already there were a nurse and a doctor in the

room.

Only a glance at her, even now, was needed to realize that it was no wonder that the Canal Zone had gone wild over the pretty screen-star. She had a figure that was truly Junoesque. Her face was as striking as her form, more especially the reddish gold of her hair and grayish blue of her eyes, which "screened" so marvelously.

I was startled, however, as we came closer to observe a number of blue-red spots on her neck, face, and arms—some no larger than a pea, others as big as a quarter-dollar— perhaps twenty of them, slightly raised above the skin.

"It's the most peculiar case," remarked the doctor, in a low tone, to Kennedy. "She seems to have regularly recurring paroxysms of chills, then fever. She's delirious and terribly nervous. You saw the spots. They are all over her body."

"You have no idea what it is?" queried Craig. The doctor shook his head.

"Ordinarily, the diagnosis of diseases in the tropics isn't more difficult than in temperate countries, but it must be gone into thoroughly, with much routine of laboratory procedure. The health authorities cooperate with us in that. Still we've not been able to determine what it is from the differential count of leukocytes, the white-cell count, study of the red cells, search for the usual parasites, even serum-reactions and blood-cultures."

"Will you give me a blood smear?" asked Kennedy.

"Surely—but it has baffled me. I've stained with gentian violet, borax-methylene blue, Leishmann's stain—and can find nothing."

He handed Kennedy a couple of slides on which were fresh little blood smears.

"I must meet him—Cardenas is his name—used to be overseer for Miguel—something to say—to me—the Café Darien—to-morrow. I must be there—Miguel—Miguel—" Marcia's voice trailed off, repeating the name of Menocal. What did it mean? Was some one going to betray some damning fact about her husband?

"A queer building—across the bay—Bay of San Blas—from the estate. I must see him—we are all Americans—North—South—oh, my poor head, my poor head!"

Kennedy bent over her soothingly, his eyes on the reddish spots on her fair skin. Suddenly, he raised her arm. For a moment he regarded some queer, regular marks, almost if they had been the scars from some small, sharp teeth. His face still lined thoughtfully, he laid the arm down abstractedly.

"I wonder whether Menocal is back—when they expect him," he considered.

"He has a house in the city," suggested Burke. "Perhaps they will know there."

"We might try," agreed Kennedy, and, a moment later we withdrew quietly from the room, leaving Connelly in the lobby of the hotel.

"You were right, Burke," pursued Kennedy, as we threaded our way through the narrow streets of the city. "She does know something—even if it is not enough."

WE found the house of Menocal without any trouble—a

beautiful place, quite in contrast with some that we passed. In

answer to our summons, the door was opened by a suave Japanese

butler whose name Burke seemed to have heard, Kayama. He bowed,

and shook his head deprecatingly in answer to our inquiry.

"Señor Menocal no at home," he replied, in labored English. "He go up-country—back to-morrow, next day."

"Señor Menocal no at home," he replied, in labored English.

"He go up-country—back to-morrow, next day."

Though not very definite, it was the best satisfaction we could get.

"You know," remarked Burke, still thinking of Marcia and her delirious words as we had turned away, "these people down here—some of them, at least—don't seem to like us any too well. Sometimes, Kennedy, it makes me boil to think how we're leaving a piece of property worth half a billion or more around loose this way. Why, we ought to take out burglary insurance on this canal. Some one'll run off with it behind our backs, 'A queer building—Bay of San Blas.' Is it his? Maybe. The Café Darien—that's over in what you might call the 'red-light district' of Panama. Say, how do we know what these spigotties who hate us are up to?"

Kennedy turned to Burke. "Where can I see Marilyn Marsh?" he asked directly.

"There's a dance over at the Tivoli, at Ancon, to-night. Almost everyone has gone to it. She's there.

"Then we'll have to go to Panama. When can we get a train?"

"There's one in less than an hour."

"And it takes?"

"A couple of hours."

"All right," agreed Kennedy. "It will be pretty late, but I'll meet you at the station. Where can I see the health officer?"

Burke directed us, and we had no difficulty in finding him.

"I've called," introduced Kennedy, "because I'm interested in the case of Miss Lamar."

The health officer shook his head.

"The case was reported to us promptly," he remarked. "We don't lose any time over these things. But I don't know what to make of it."

For several moments they chatted about the measures adopted for safeguarding health, Kennedy leading the conversation from Stegomyia to Anopheles and other insect pests.

"By the way," he remarked, "what measures do you adopt against other vermin?"

"We have our official rat-catcher," smiled the doctor, "armed with a Flobert rifle and a pocketful of poison."

"Has he reported anything out of the way lately?"

"Why, yes," he replied quickly; "and it's strange, too. Only the other day he killed two white rats—ferociously hungry fellows they were—back of the hotel."

Kennedy was alert in an instant.

"Have you kept the bodies?" he asked quickly.

"Of course. They went to the bacteriologist. Why?"

"I'm interested in them."

"I'll have them sent to you."

"Will you?" thanked Kennedy. "Let me have them to-morrow."

We had just time now to dash for the train and Burke.

PANAMA, even in the darkness, impressed me as being quite

different from Colon. Most of the shops on the main street

opposite the railway station were closed. Other streets were

graded and paved, though some picturesquely crooked streets were

left.

Burke succeeded in getting us to the Tivoli while the dance was at its height. For a moment, we paused in a doorway, while Burke cast his eye over the dancers, trying to pick out Marilyn Marsh.

I could not help feeling that it was strangely like a suburban affair of the same sort at home, except for the men in their crisp white linen. There were some señoritas of the republic, dark-skinned beauties, but, for the most part, the gowns, the conversation, the manners of the women were quite like those at home. The canal-force had dwindled since the virtual completion of the work, but there was still a fair sprinkling, and tourists made up a large number.

Burke had no need to point Marilyn out. Even before he did so, I had seen her, and was impressed by the remarkable resemblance to Marcia. Marilyn was quite of the same type, tall, almost statuesque. Except for the blonder shade of her hair, one might readily have mistaken them at a short distance.

"There's Werner," added Burke, a moment later, when the encore of the dance ceased and he edged his way across the floor in their direction.

We had but to watch a few moments to see that Werner was indeed very attentive to her, but I fancied that there was some constraint on the part of Marilyn.

Burke introduced us, and it fell to my lot to listen more to Werner than to Marilyn. Like most people of leisure who have traveled, I found that he was a very fascinating fellow. Apparently, he was more than a mere globe-trotter, too. He had been somewhat of the sportsman.

"To-morrow," he remarked, after we had chatted a few moments, "I am going to do the unusual. I shall return to Colon through the jungle. I love it—its an almost unbelievable tangle of palms, mahogany, cocobolo, lignum-vitae—the vines and creepers, ferns and grasses, and orchids. I've had a taste of it. You know, people come here and don't seem to realize that only a few miles away are the tapirs, the sloths, the iguana, the giant lizards, the boas and snakes—just as they were in the days of Balboa."

"You can't blame them," put in Kennedy hastily. "The jungle has its sinister aspect, the same menace that it had then— perhaps others."

I saw Craig watching Werner covertly. Had his enthusiasm for the jungle been a pose to cover something else? At any rate, he betrayed nothing at the broad remark of Kennedy.

I saw Craig watching Werner covertly. Had his enthusiasm

for the jungle been a pose to cover something else?

There followed a byplay of small talk which I did not appreciate until I saw that, by the next dance, it had temporarily eliminated Werner. Craig had maneuvered until we were alone with Marilyn, and, instead of dancing, sauntered to the far end of the porch.

It was a beautiful night, and we looked out over the dark blue of the sea, a blue such as I have rarely seen before while above glowed the myriad stars, the fiery Southern Cross standing out among them in the dear air. A brilliant moon had risen from the Pacific—a sight that in the Western Hemisphere is unique, for one hardly realizes that the Isthmus is like the letter S, with Colon, on the Caribbean, to the west, and Panama, on the Pacific, to the east. Suddenly, Kennedy paused as we walked, and faced Marilyn.

"Miss Marsh," he said in a low, tense voice, "I think we understand each other. My introduction by Mr. Burke is sufficient to tell why I am here. Would you accept a commission—dangerous perhaps—for your country?"

She returned his gaze with fearless eyes.

"What is it?" she asked simply.

"Marcia Lamar," he replied, after a moment, telling her of the illness and delirium, "was to meet a man, Cardenas, a former overseer for Menocal. He was to make some revelation to her—here in Panama—at the Café Darien. To-morrow, I want you to meet him. I want you to pose as Marcia Lamar. A little make-up; he will not know. It involves going into the so-called 'red-light district'—" He paused.

"I will do it," she answered quickly.

We rejoined the others so as not to excite suspicion, and the dance broke up shortly, for it was already late when we had arrived.

CRAIG and I were about early the following morning, but not

quite early enough. Burke was nowhere to be found. Werner, it

seemed, had started on horseback, almost at delight, and Burke

had left a hasty note saying that he had followed him. Kennedy

was eager to get back to Colon now, and, after a hasty conference

with Marilyn, determined that nothing better could be done than

to leave her alone to carry out the mission which the stray words

of Marcia had suggested.

"Depend on me," Marilyn assured us bravely. "If I don't succeed at first, I shall keep on. It is a service I would render in war, why not in peace—perhaps to prevent war?"

"A wonderful woman!" was Craig's comment, as we bade her good luck and hastened to the railway station. "And you will see—America would produce thousands if the crisis called."

OUR return trip was quite different in the daylight from the

hasty journey at night. Then it was evident that it was not so

much a canal we had built as two lakes. These had been joined by

a canal nine miles long, cutting the intervening ridge.

It happened that on the train one of the canal engineers introduced himself. From him we heard of the wavelike formation of the slides at the cut, which the giant dredges were now at work removing. From him we learned of the peculiarly unstable nature of the volcanic soil, the overlying material resting on rock or something harder than itself which sloped toward the canal. The weight seemed to have overcome the frictional resistance, as if the underlayers were soft and were literally squeezed out, both at Culebra and Cucaracha. Instead of the angle of rest being one foot vertical to two horizontal, it was something like one to seven. Slides there had been into the canal-prism before, until equilibrium was approached. But these last ones had been started by something outside. I recalled Burke's theory of bombs dropped from aeroplanes—or perhaps placed by the flier.

We returned to Colon to find that Marcia was no better, and Kennedy lost no time in getting the carcasses of the two rats from the health authorities. Back in our room, he unpacked part of his traveling laboratory and began at once an examination both of the bodies of the rats and of the blood smears from Marcia, using his high-powered microscope.

Werner arrived safely, having completed his trip across in much better than the usual time. He was full of the glories of the jungle. I wondered whether he had made any digression from the main route. If he had, it could not have been far.

Late as it was, there was no word from Burke. Nor had we heard anything from Marilyn. But we recalled her last words—that she would succeed, no matter how long it look.

Kennedy's microscopic studies had been more than ordinarily exacting and, though he said little about them, I gathered from his manner that he was on the trail of something quite unusual. He also got Connelly to repeat what he had already told Burke about his trip to Menocal's estate and the strange noises in the air he had heard.

Menocal, it appeared from Connelly's description, was a very polished, suave, well-educated gentleman, with a taste for French brandy, cars, and feminine beauty, all of which seemed to have impressed the motion-picture director more than anything else about the man. He had not found anything on the estate which he wanted to make use of in his film, and what else he could tell us did not seem to have any value for the matter now uppermost in Kennedy's mind.

Werner was a different problem. Instinctively, I felt that he knew we were watching him. Personally, I could not say that I disliked the man, but his was the type that led me to be willing to credit him with almost anything except lack of cleverness. He might be an emissary of some secret foreign interest and still cover it up by something quite safe on the surface. Or he might, for the sheer delight of adventure, engage in something in the very case in which we were interested for the sole satisfaction of being able to boast of how he surpassed Burke at his own game. He was baffling, and he knew it and took pleasure in it.

MIDNIGHT came, and still no word from Burke, and not likely to

be now until the next day. Both Connelly and Werner had retired.

Kennedy, however, had no intention of resting merely because we

were alone. Making sure that no one, as far as we could judge,

was observing us, we managed to slip out of a side entrance of

the hotel and make our way through the town. We had not gone far

before familiar landmarks indicated to me that he was bound for

Menocal's place.

The house seemed as deserted as ever, and twice Kennedy and I went round it to make sure that Menocal had not returned. We were standing in the rear, the part presided over by the faithful Kayama, contemplating the windows for any sign of life, when a noise in a little shed behind attracted our attention. Kennedy opened the latched wooden door and flashed his pocket search-light into the shed. There, in a cage, were two white rats.

In a corner lay a large piece of canvas. Kennedy picked it up and threw it over the cage. Underneath, he broke a small bottle of chloroform. Ten minutes later, we were on our way back to the hotel, the two dead rats wrapped carefully in a strip of the canvas.

EARLY the following morning, Kennedy was at work supplementing

the studies had already made. Finally, I asked:

"Is it poison?"

"No," he replied slowly; "though I can't say that I think it strange that they should not have known what was the matter. You know it sometimes happens that a carefully-formulated description of an unfamiliar group of symptoms brings other cases to light. The only thing was that I happened to have heard of this thing before. So it is that cases grow in number as medical attention is directed to them, and a condition which was infrequently recognized loses its rarity. That is the case in this instance." He pointed me toward the microscope. "Look through it," he said simply. "I have tried staining it with hematoxylin. Can you see anything?"

I nodded. Just visible were some fine lines, branching filaments, threadlike.

"That is the Streptothrix muris ratti," explained Kennedy. "No; it's not a poison. It's a fever, the now rather unknown rat-bite fever."

"Rat-bite fever?" I questioned.

"A disease that develops, just as name implies. It appears after a latent incubation of several days. You saw those little marks on Marcia's arms? Some one may have loosed rats in her room at night. Perhaps the bite healed long before the disease appeared."

It was something to have solved the mystery of the peculiar disease. Where and why, however, had come the attack on Marcia?

OUTSIDE I heard a noise, and, glancing from the window, saw a

native cart before the main entrance to the hotel.

"Burke!" I cried, recognizing the face of a man, half sitting, half lying in the cart.

It was indeed the secret-service man, pale and weak, his head bound up tightly. Exhausted by the jolting of the cart, he had to be assisted by the native to get out. We were at his side in a moment.

"What's the matter?" asked Kennedy, seizing his arm and gently supporting him to an easy chair on the veranda.

Burke looked about weakly.

"Did he get here all right?" he asked.

"Yes," nodded Kennedy; "but what happened to you?"

"I was following him. Some one must have been following me. I was struck down from behind. I don't know how—didn't know a thing until this native picked me up half dead—too late to get here last night."

"Then you found out nothing? You don't even know who did it?"

"Not unless it was some one working for him," ruminated Burke. "If he got here all right and in time—it might have been some one trying to throw suspicion on him," he added, as if loath also to give up the idea that Menocal was at the bottom of It.

Burke's mishap added greatly to our anxiety for Marilyn. Craig was still considering what was best to be done when Connelly, who had evidently been searching all over, caught sight of us.

"Say," he asked anxiously, "isn't there anything that can be done for Marcia? She's having another of those attacks—only worse. By George, what's the matter with you, Burke?"

Hurriedly we told him, while Kennedy excused himself a moment to get something from his traveling laboratory, then rejoined us.

AS we entered Marcia's room, it was evident that less than a

day had made a remarkable change in her. She lay there,

alternately moaning for Menocal and, I gathered, upbraiding him

for something. The doctor seemed helpless. She had responded to

no treatment that he had given, and he was at his wits' end.

Without a word, Kennedy drew a hypodermic needle from a case and a little bottle of yellowish liquid from his pocket. Carefully he selected a vein in her arm and punctured it with the needle.

"It seems to be a disease related to the Russian relapsing fever," he remarked, leaving to me as best I could to explain to the others what he had discovered. "Salvarsan will cure the trouble," he concluded simply, as, a few minutes later, he dropped the needle back into its case.

"Señor Menocal," announced a servant.

Kennedy signed quickly to let him in. An instant later, he burst in with true Latin emotion. Some one had evidently told him of Marcia's illness, which was not strange, for everyone knew by this time.

He seemed not to see or care about us as he knelt by the bed and fondly stroked her burning forehead. Instinctively she seemed to recognize his touch. Her face brightened, and between his return and the hypodermic, I could see a marked change already.

"You—you were gone—longer than—you expected." she murmured.

I wondered whether it might not be her indirect way of accusing him, for never for an instant had it seemed that she had forgotten that she was in a terribly trying position, trying to reconcile loyalty to country with what she evidently feared of him. I think Kennedy shared my own feeling now—that in some way she had excited the fear of another, who felt safe with her out of the way.

"The trouble with the men on the plantation was more serious than I had expected," Menocal replied earnestly. "I came back the moment I could get away—only to find you—so. Madre de Dios—I would have lost the whole crew rather than have left you, if I had known this! Tell me—you are getting better?"

She smiled at him wanly as he poured forth his excuses. On the surface, he had a perfectly valid explanation. She seemed to catch at it, to be eager to accept it.

"A lady in the lobby to see you, sir," interrupted a boy, singling out Kennedy.

It was Marilyn Marsh, safe at last. Craig greeted her with unconcealed joy.

"He didn't appear until too late to get here yesterday," she began, as if bursting with information, "and then I thought I had better meet him again to-day, to make sure that I got all—"

"Nothing—here," cautioned Craig, with a gesture of silence.

He looked about. Only at that end where the porch roof had been crushed by the flechettes was it deserted. That had none too savory associations. He turned and led the way to an alcove inside.

"Then you discovered something?" he asked eagerly.

"Indeed, yes," she replied, brimming with enthusiasm. "There is a plot. Somewhere up-country—without a doubt at the Bay of San Blas—there is a secret aero-base—ready for use at any time—not for war, now, of course, but for scouting, laying plans. They must be working schemes for blowing up the locks at Gatun and Miraflores—to be ready to strike instantly—if ever needed."

"And the slides?" put in Burke, who had joined us.

"Merely an experiment—to test what can be done."

"How did you find out?" asked Craig.

She laughed merrily.

"This Cardenas, I think, is a labor agitator. He learned from some workmen across the bay. I led him on—he is very susceptible—then left him." She laughed again at the thought of how she had carried out the hoax. "Seriously, though," she added, "it seems to be a gigantic scheme of some foreign agents to seize the canal from the air—wreck the forts on the Near Islands and, over here, cut off the Isthmus' wireless from Arlington, blow up the locks and create slides—anything to close the canal—if necessary. That would divide the fleet. I believe they're working on the data of the forts and guns here now."

"But who are 'they'?" insisted Craig.

She shook her pretty head.

"Cardenas thinks it's Menocal, but Cardenas is somewhat of a blackmailer, I gather. The señor would not be shaken down for money. There's some animus in it, I'm afraid. But it's some one, there's a representative—perhaps the real head—here in Colon."

Whoever it was, it was now more evident than ever that he had covered himself perfectly. I wondered whether Marilyn might not, in a measure, be in the same position as Marcia. Did she, in turn, suspect Werner, and was she trying to divert attention from him? Whatever of her intuitions she had left unsaid, it was plain that she at last had discovered the facts.

We saw nothing yet of Werner, but there was now no time to seek him, for Craig and Burke were hastily sketching out a plan. Weak as he still was, Burke immediately got in touch with the authorities and arranged that that night there should be armed patrols at the locks and other important places. The special lighting-arrangements at Gatun, Miraflores, and Pedro Miguel, which gave them almost the brightness of day at night, were to be dimmed black. All over were to be cordons of the famous Zone police, most of them former army men.

However, such measures did not appeal to Kennedy, who realized how futile they were when the danger was not from earth, but above. He set hastily to work, putting together an invention which he had evolved some time before we had left New York, and had brought with him—a peculiar little instrument containing a novel electric cell.

Through Burke, we were able to gain admittance to the fort on the headland jutting out into the Caribbean, where were placed the fourteen-inch mortars and sixteen-inch guns which now seemed so to interest the foreign spies in the Zone. On each of several aeroplane guns Craig placed his new secret attachment.

THE day had worn away almost before we knew it, and, whatever

might be the measures we adopted against the terror in the air,

we knew that there was other—perhaps greater—game

still uncaught, here among us. Craig and I returned to the hotel

after he had given the most elaborate explanation and instruction

to the men at the coast-defense station.

It was galling to feel that there was nothing that we could do but wait. A trip out to the suspected spot, even if it could be located, on the bay was out of the question until the following day. Burke had already made arrangements for that, and we were at liberty to join it, if we thought best. However, there was too much to keep us in Colon at the moment. More than that, as Kennedy pointed out, our secret foe must by this time have learned how close we were getting to him. If any new move was to be expected, it was altogether probable that he would make it, and that it would be made at us without our going to seek it. There was a fine flavor of danger in the thought. What unseen peril would menace us next?

IT was nightfall before we reached the hotel again and found

Marilyn Marsh waiting for us anxiously.

"Have you seen Mr. Werner to-day?" inquired Kennedy eagerly, feeling sure that if he were about it was more likely that he would find Marilyn than anyone else.

"Yes," she replied quickly, with unconcealed perplexity; "he was here the afternoon, after you left. It's strange. I can't make it out, but Mr. Werner seems to be watching Señor Menocal so sharply. Marcia has been growing steadily better, and, this afternoon, when Señor Menocal left the hotel, I noticed that Mr. Werner was waiting to see what he would do."

"Where's Werner now?"

"I think he followed Señor Menocal."

A THIRD time, Kennedy and I sought Menocal's house. But now it

seemed absolutely deserted, even by the faithful Kayama. We

returned to find Burke resting on the porch, chatting with

Marilyn.

"Perhaps he was on the same quest as yourself," she was saying. "And some one 'got' me, instead of him?" queried Burke, evidently discussing his almost fatal encounter in the jungle.

"It might be. People know who you are; they don't know him," she suggested; and I felt that whatever she might suspect, at least she would like to have her explanation the true one.

"You bet they don't know him," responded Burke cordially.

"Look!"

Marilyn had sprung forward to the railing of the porch, and was peering through the fine-mesh screen at something. We were at her side instantly.

Marilyn had sprung forward to the railing of the porch,

and was peering through the fine-mesh screen at something.

A long finger of light from the sky was sweeping toward us. Slowly its rays turned, as though both the source of the light were unstable and its direction were being modified to locate something. On it swept, toward the headland.

"Some one on an aeroplane—trying to locate the gun-emplacements," muttered Kennedy.

The ray rested at last, as if it had found that at which it was directed.

Kennedy was almost frantic with impatience.

"Keep it fixed—one more minute!" he muttered, as if daring someone.

Suddenly, there came a sharp, distant bark of a gun—another—and another!

"My selenium range-finder!" cried Craig excitedly. "A ray of light makes a little selenium cell a conductor of electricity—completes the circuit. My arrangement points the gun—explodes the charge—along the path of the beam—"

There was a sharp, stifled cry from Marilyn. The beam of light in the sky seemed falling. One shot had struck.

"Come on!" urged Kennedy, swinging open the screen door and dashing out.

We followed in the direction of the falling beam. Burke, on account of his injuries, could go only slowly. Between us, Marilyn and I took his arms, while Craig forged ahead of us.

We had not gone far when I noticed a figure in front of us, and behind him another, as though dogging his steps.

As the figure ahead passed under a light I saw, to my surprise, that it was Menocal.

We had come abreast of the man trailing him.

"Marilyn!"

"Then—you are—with us?"

"You didn't think I was against you did you?" It was Werner. "I knew the disease," he panted. "It's the sakoda, as they call it in Japan. The only question in my mind was which of them was responsible."

We were now up to Craig, bending over a battered air-plane. Menocal had dropped down beside him.

"Yes—there were papers on him," muttered Craig. "You may show them to Marcia."

We, too, bent down. In the tangle of the wreckage lay the motionless body of Kayama, who had used Menocal as his cover.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.