RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Cosmopolitan, August 1915, with "The Evil Eye"

The Spanish conquest brought about a lasting feud between the Peruvian race and the invaders. This is a matter of history. Who would not, therefore, when the outward circumstances of this strange case became known, at once link the old Castilian and the haughty Peruvian woman in the chain of causality? But Craig Kennedy never jumps at conclusions. He seeks the firm ground of fact that can be established by scientific research. In his long experience he has learned to expect any result. Consequently he never wastes time on even what seem the most promising clues. Herein lies one of the chief differences between the scientific and the old-school detective. This interesting point is clearly brought out in the following story.

"YOU don't know the woman who is causing the trouble. You haven't seen her eyes. But, Madre de Dios!—my father is a changed man. Sometimes I think he is—what you call—mad!"

Our visitor spoke in a hurried, nervous tone, with a marked foreign accent which was not at all unpleasing. She was a young woman, unmistakably beautiful, of the dark Spanish type and apparently a South American.

"I am Señorita Inez de Mendoza, of Lima, Peru," she introduced herself, as she leaned forward in the wing chair in a high state of overwrought excitement. "We have been in this country only a short time—my father and I, with his partner in a mining venture, Mr. Lockwood. Since the hot weather came, we have been staying at the Beach Inn, at Atlantic Beach."

She paused a moment and hesitated, as though, in this strange land she had no idea of which way to turn for help.

"Perhaps I should have gone to see a doctor about him," she considered doubtfully. Then her emotions got the better of her, and she went on passionately: "But, Mr. Kennedy, it is not a case for a doctor. It is a case for a detective—for some one who is more than a detective."

She spoke pleadingly now, in a soft, musical voice that was far more pleasing to the ear than that of the usual Spanish-American. I had heard that the women of Lima were famed for their beauty and melodious voices. Señorita Mendoza surely upheld their reputation.

There was an appealing look in her soft brown eyes, and her thin, delicate lips trembled as she hurried on with her story.

"I never saw my father in such a state before," she murmured. "All he talks about is the 'Big Fish'—whatever that may mean—and the curse of Mansiché. Sometimes I think he has a violent fever. He is excited—and seems to be wasting away. He seems to see strange visions and hear voices. Yet I think he is worse when he is quiet in a dark room, alone, than when he is down in the lobby of the hotel in the midst of the crowd." A sudden flash of fire seemed to light up her dark eyes. "There is a woman at the hotel, too," she went on, "a woman from Trujillo, Señora de Moche. Ever since she has been there, my father has been growing worse and worse."

"Who is this Señora de Moche?" asked Kennedy.

"A Peruvian of an old Indian family," she replied. "She has come to New York with her son Alfonso, who is studying at the university here. I knew him in Peru," she added, as if by way of confession, "when he was a student at the university at Lima."

There was something in both her tone and her manner that would lead one to believe that she bore no enmity toward the son—indeed, quite the contrary—whatever might be her feelings toward the mother.

Kennedy reached for our university catalogue and found the name, Alfonso de Moche, a postgraduate student in the School of Engineering, and therefore not in any of Kennedy's own courses. I could see that he was growing interested.

"And you think," he queried, "that, in some way, this woman is connected with the strange change that has taken place in your father?"

"I don't know," she temporized; but the tone of her answer was sufficient to convey the impression that, in her heart, she did suspect something, she knew not what.

"It's not a long run to Atlantic Beach," considered Kennedy. "I have one or two things that I must finish up first, however."

"Then you will come down to-night?" she asked, as Kennedy rose and took the little gloved hand which she extended.

"To-night, surely," answered Craig, holding the door for her to pass out.

"Well," I said, when we were alone, "what is it—a romance or a crime?"

"Both, I think," he replied abstractedly, taking up the experiment which the visit had interrupted.

FOR more than an hour, Kennedy delved into archeological lore. Then he rejoined me at the laboratory, and, after a hasty bite of dinner, we hurried down to the station.

That evening we stepped off the train at Atlantic Beach to make our way to the Beach Inn. The resort was just springing into night life. There was something intoxicating about the combination of the bracing salt air and the gay throngs seeking pleasure.

Instead of taking the hotel 'bus, Kennedy decided to stroll to the Inn along the Boardwalk. We were just about to turn into the miniature park which separated the inn from the walk, when we noticed a wheel-chair coming in our direction. In it were a young man and a woman of well-preserved middle age. They had evidently been enjoying the ocean breeze after dinner, and the sound of music had drawn them back to the hotel.

We entered the lobby of the Inn just as the first number of the evening concert was finishing. Kennedy stood at the desk for a moment, while Señorita Mendoza was being paged, and ran his eye over the brilliant scene. In a minute, the boy returned and led us through the maze of wicker chairs to an alcove just off the hall which, later in the evening, would be turned into a ballroom.

On a wide settee, the señorita was talking with animation to a tall, clean-cut young man in evening clothes, whose face bore the tan of a sun much stronger than that at Atlantic Beach. He was unmistakably of the type of American soldier of fortune. In a deep rocker before them, sat a heavy-set man, whose piercing black eyes beetled forth from under bushy eyebrows. He was rather distinguished-looking, and his close-cropped hair and mustache set him off as a man of affairs and consequence.

As we approached, Señorita Mendoza rose quickly. I wondered how she was going to get over the awkward situation of introducing us, for surely she did not intend to let her father know that she was employing a detective. She did it most cleverly.

"Good-evening; I am delighted to see you," she greeted. Then, turning to her father, she introduced Craig. "This is Professor Kennedy," she explained, "whom I met at the reception of the Hispano-American Society. You remember I told you he was so much interested in our Peruvian ruins."

Don Luis's eyes seemed fairly to glitter with excitement. They were prominent, staring eyes.

"Then, Señor Kennedy," he exclaimed, "you know of our ruins of Chan-Chan, of Chimu—those wonderful places—and have heard the legend of the Peje grande?" His eyes, by that time, were almost starting from their sockets, and I noticed that the pupils were dilated almost to the size of the iris. "We must sit down," he went on, "and talk about Peru."

The soldier of fortune also had risen as we approached. In her soft, musical voice, the señorita now interrupted her father.

"Professor Kennedy, let me introduce you to Mr. Lockwood, my father's partner in a mining project which brings us to New York."

As Kennedy and I shook hands with the young mining engineer, I felt that Lockwood was something more to her than a mere partner in her father's mining venture. We drew up chairs and joined the circle.

Kennedy said something about mining, and the very word "mine" seemed to excite Señor Mendoza still further.

"Your American financiers have lost millions in mining in Peru," he exclaimed excitedly, taking out a beautifully chased gold cigarette-case, "but we are going to make more millions than they ever dreamed of, because we are simply going to mine for the products of centuries of labor already done, for the great treasure of Trujillo."

He opened the cigarette-case and handed it about. The cigarettes seemed to be his own special brand. We lighted up and puffed away for a moment. There was a peculiar taste about them, however, which I did not like. In fact, I think that the Latin-American cigarettes do not seem to appeal very much to an American.

As we talked, I noticed that Kennedy evidently shared my own tastes, for he allowed his cigarette to go out, and, after a puff or two, I did the same.

"We are not the only ones who have sought the Peje grande," resumed Mendoza eagerly, "but we are the only ones who are seeking it in the right place and," he added, leaning over with a whisper, "I am the only one who has the concession, the monopoly from the government to seek in what we know to be the right place. Others have found the Little Fish. We shall find the Big Fish."

He had raised his voice from the whisper, and I caught the señorita looking anxiously at Kennedy, as much as to say: "You see? His mind is full of only one subject."

Señor Mendoza's eyes had wandered from us, and he seemed all of a sudden to grow wild.

"We shall find it," he cried, "no matter what obstacles man or devil puts in our way! It is ours—for a simple piece of engineering—ours! The curse of Mansiché—pouf!"

He snapped his fingers almost defiantly as he said it in a high-pitched voice. There was an air of bravado about him, and I could not help feeling that perhaps in his heart he was not so sure of himself as he would have others think. It was as though some diabolical force had taken possession of his brain and he would fight it off.

Kennedy quickly followed the staring glance of Mendoza. Out on the broad veranda, by an open window a few yards from us, sat the woman of the wheel-chair. The young man who accompanied her had his back toward us for the moment, but she was looking fixedly in our direction, paying no attention apparently to the music. She was a large woman, with dark hair and full, red lips. Her face had a slight copper swarthiness about it.

But it was her eyes that arrested and held one's attention. Whether it was in the eyes themselves or in the way that she used them, there could be no mistake about the hypnotic power that their owner wielded. She saw us looking at her, but it made no difference. Not for an instant did she allow our gaze to distract her in the projection of their weird power straight at Don Luis himself.

Don Luis, on his part, seemed fascinated.

He rose, and, for a moment, I thought that he was going over to speak to her, as if drawn by that intangible attraction which Poe has so cleverly expressed in his "Imp of the Perverse." Instead, in the midst of the number which the orchestra was playing, he turned and, as though by a superhuman effort, moved away among the guests out into the lobby.

I glanced up in time to see the anxious look on the señorita's face change momentarily into a flash of hatred toward the woman in the window.

The young man turned just about that time, and there was no mistaking the ardent glance he directed toward the fair Peruvian. I fancied that her face softened a bit, too. She resumed her normal composure as she said to Lock wood:

"You will excuse me, I know. Father is tired of the music I think I will take him for a turn down the Boardwalk. If you can join us in our rooms in an hour or so, may we see you?" she asked, with another significant glance at Kennedy.

She was gone before Craig barely had time to reply that we should be delighted. Evidently she did not dare let her father get very far out of her sight.

We sat for a few moments smoking and chatting with Lockwood.

"What is the curse of Mansiché?" asked Kennedy.

"Oh, I don't know," returned Lockwood, impatiently flicking the ashes from his cigar, as though such stories had no interest for the practical mind of an engineer; "some old superstition. I don't know much about the story; but I do know that there is treasure in that great old Chimu mound near Trujillo, and that Don Luis has got us a government concession to bore into it, if we can only raise the capital to carry it out."

Kennedy showed no disposition to leave the academic and become interested in the thing from the financial standpoint, and the conversation dragged.

"I beg pardon," apologized Lockwood, at length, "but I have some very important letters that I must get off before the mail closes. I'll see you, I presume, when the señorita and Don Luis come back?"

Kennedy nodded. In fact, I think he was rather glad of the opportunity to look things over unhampered.

Señora de Moche—for I had no doubt, now, that this was the Peruvian-Indian woman of whom Señorita Inez had spoken—seemed to lose interest in us and in the concert the moment Don Luis went out. Her son also seemed restive. He was a good-looking fellow, with high forehead, nose slightly aquiline, chin and mouth firm; in fact, his whole face was refined and intellectual, though tinged with melancholy.

We strolled down the wide veranda, and, as we passed the woman and her son, I was conscious of that strange feeling—which psychologists tell us, however, has no foundation—of being stared at from behind.

Kennedy turned suddenly, and again we passed, just in time to catch, in a low tone, from the young man:

"Yes, I have seen him at the university. Everyone knows that he—"

The rest was lost.

It was quite evident, now, that they thought we were interested in them. There was, then, no use in our watching them further. Indeed, when we turned again, we found that the señora and Alfonso were making their way slowly to the elevator.

THE door of the elevator had scarcely closed when Kennedy turned on his heel and quickly made his way back to the alcove where we had been sitting. Lying about on the ash-tray on a little wicker table were several of Mendoza's half-burned cigarettes. We sat down a moment and, after a hasty glance around, Craig gathered them up and folded them in a piece of paper. In a leisurely manner he strolled over to the desk, and, as guests in a summer hotel will do, looked over the register. The Mendozas, father and daughter, were registered in rooms 810 and 812, a suite on the eighth floor. Lockwood was across the hall, in 811.

Turning the pages, Kennedy paused, then nudged me. Señora de Moche and Señor Alfonso de Moche were on the same floor, in 839 and 841.

Kennedy said nothing, but glanced at his watch. We had still nearly three-quarters of an hour to wait until our pretty client returned.

"There's no use in wasting time or in trying to conceal our identity," he said finally, drawing a card from his pocket and handing it to the clerk. "Señora de Moche, please."

Much to my surprise, the señora telephoned down that she would see us in her own sitting-room.

Alfonso was out, and the señora was alone.

"I hope that you will pardon me," began Craig, with an elaborate explanation, "but I have become interested in an opportunity to invest in a Peruvian venture, and they tell me at the office that you are a Peruvian. I thought that perhaps you could advise me."

She looked at us keenly. I fancied that she detected the subterfuge; yet she did not try to avoid us. On closer view, her eyes were really remarkable—those of a woman endowed with an abundance of health and energy—eyes that were full of what the old phrenologists used to call amativeness, denoting a nature capable of intense passion, whether of love or hate.

She looked at us keenly. I fancied that she detected the subterfuge.

"I suppose you mean that scheme of Señor Mendoza and his friend, Mr. Lockwood," she returned, speaking rapidly. "Let me tell you about it. You may know that the Chimu tribes in the North were the wealthiest at the time of the coming of the Spaniards. Well, they had a custom of burying with their dead all their movable property. Sometimes a common grave, or huaca, was given to many. That would become a cache of treasure.

"Back in the seventeenth century," she continued, leaning forward eagerly as she talked, "a Spaniard opened a Chimu huaca and found gold that is said to have been worth a million dollars. An Indian told him of it. After he had shown him the treasure, the Indian told the Spaniard that he had given him only the Little Fish, the Peje chica, but that, some day, he would give him the Big Fish, the Peje grande.

"The Indian died," she went on solemnly, flashing at Craig a glance from her wonderful eyes. "He was poisoned by the other members of his tribe." She paused, then added, "That is my tribe, my family." She paused again a moment. "The Big Fish is still a secret—or at least it was until they got it from my brother, to whom the tradition had been entrusted. They drove him crazy—until he talked. Then, after he had told the secret and lost his mind, he threw himself one day into Lake Titicaca."

She stopped dramatically in her passionate outpouring of the tragedies that had followed the hidden treasure.

"I cannot tell you more than you probably already know," she resumed, watching our faces intently. "You know, I suppose, that the treasure is believed to be in a large mound—a tumulus, I think you call it—visible from our town of Trujillo. Many people have tried to open it, but the mass of sand pours down on them and they have been discouraged. But Señor Mendoza believes that he knows just where to bore, and Mr. Lockwood has a plan for a well-timbered tunnel which can be driven at the right point."

She said it with a sort of quiet assurance that conveyed the impression, without her saying it, that the venture was somehow doomed to failure, that these desecraters were merely toying with fate. All through her remarks one could feel that she suspected Mendoza of having been responsible for the downfall and tragedy of her brother, who had betrayed the age-old secret.

Her eyes assumed a far-away, dreamy look as she went on.

"You must know that we Peruvians have been so educated that we never explore ruins for hidden treasure—not even if we have the knowledge of engineering to do so." Apparently she was thinking of her son and his studies at the university. One could follow her thoughts as they flitted from him to the beautiful girl with whom she had seen us. "We are a peculiar race," she proceeded. "We seldom intermarry with other races. We are proud of our unmixed lineage."

She said it with a quiet dignity, quite in contrast with the nervous, hasty manner of Don Luis. There was no doubt that the feeling cut deep. Kennedy had been following her closely and I could see that the cross-currents of superstition, avarice, and race hatred in the case presented a tangle that challenged him.

"Thank you," he murmured, rising; "you have told me quite enough to make me think seriously before I join in any such undertaking."

She smiled enigmatically, and we bowed ourselves out.

"A most baffling woman," was Craig's only comment, as we rode down again in the elevator to wait for the return of Don Luis and the señorita.

Scarcely had their chair set them down at the Inn than Alfonso seemed to appear from nowhere. He had evidently been waiting in the shadow of the porch for them.

We stood aside and watched the little drama. For a few minutes the señorita talked with him. One did not need to be told that she had a deep regard for the young man. She wanted to see him; yet she did not want to see him. Don Luis, on the contrary, seemed to become quite restive and impatient again and to wish to cut the conversation short.

It was evident that Alfonso was deeply in love with Inez. I wondered whether, after all, the trouble was that the proud old Castilian, Don Luis, would never consent to the marriage of his daughter to one of Indian blood?

In any event, one could easily imagine the feelings of Alfonso toward Lockwood, whom he saw carrying off the prize under his very eyes. As for his mother, we had seen that the Peruvians of her caste were a proud old race. Her son was the apple of her eye. Who were these to scorn her race, her family?

It was a little more than an hour after our first meeting when the party—including Lock wood—gathered again up in the rooms of the Mendozas.

It was a delightful evening, even in spite of the tension under which we were. We chatted about everything from archeology to Wall Street, until I could well fancy how anyone possessed of an imagination susceptible to the influence of mystery and tradition would succumb to the glittering charm of the magic words, "Peje chica" and feel all the gold-hunter's enthusiasm when brought into the atmosphere of the "Peje grande." Visions of hidden treasure seemed to throw a glamour over everything. Kennedy and the señorita had moved over to a window where they were gazing out on the fairy-land of Atlantic Beach spread out before them, while Lockwood and Don Luis were eagerly quizzing me on the possibilities of newspaper publicity.

"Oh, Professor Kennedy," I heard her say, under her breath, "sometimes I fear that it is the mal de ojo—the evil eye."

I did not catch Craig's answer, but I did catch him time and time again narrowly observing Don Luis. Our host was smoking furiously now, and his eyes had, even more than before, that peculiar, staring look. By the way his veins stood out, I could see that Mendoza's heart action must be rapid. He was talking more and more wildly as he grew more excited. Even Lockwood noticed it and, I thought, frowned. Slowly the conviction was forced on me. The man was mad—raving mad!

"Really, I must get back to the city tonight," I overheard Craig say to the señorita, as finally he turned from the window. Her face clouded, but she said nothing.

"If you could arrange to have us dine with you to-morrow night up here," he added quickly, in a whisper, "I think I might be prepared to take some action."

"By all means," she replied eagerly, catching at anything that promised aid.

ON the late train back, I half dozed, wondering what had caused Mendoza's evident madness. Was it a sort of auto-hypnotism? There was, I knew, a form of illusion known as opthalmophobia—fear of the eye. It ranged from mere aversion to being gazed at all the way to the subjective development of real physical illness out of otherwise trifling ailments. If not that, what object could there be for anyone to cause such a condition? Might it be for robbery, or might it be for revenge?

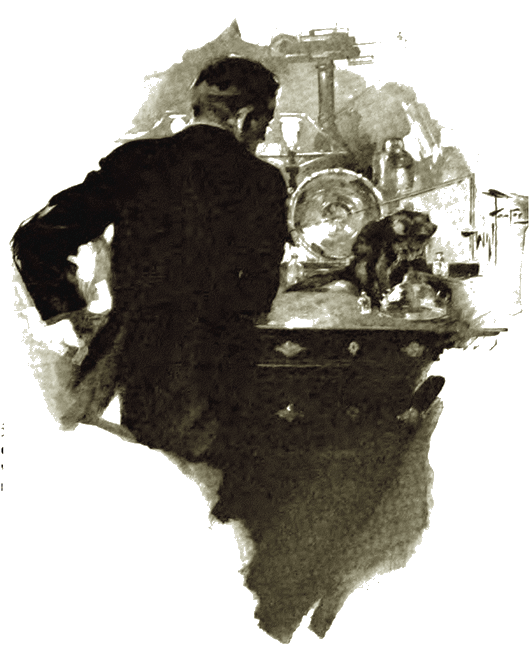

Back in the laboratory, Kennedy pulled out from a cabinet a peculiar apparatus. It seemed to consist of a sort of triangular prism set with its edge vertically on a rigid platform attached to a massive stand.

Next, he lighted one of the cigarette stubs which he had carried away so carefully. The smoke curled up between a powerful light and the peculiar instrument, while Craig peered through a lens, manipulating the thing with patience and skill.

Finally, he beckoned me over, and I looked through, too. All I could see was a number of strange lines on a sort of fine grating.

"That," he explained, in answer to my unspoken question, as I continued to gaze, "is one of the latest forms of the spectroscope, known as the interferometer, with delicately ruled gratings in which power to resolve the straight, close lines in the spectrum is carried to the limit of possibility. A small watch is delicate, but it bears no comparison to the delicacy of these defraction spectroscopes.

"Every substance, you know, is, when radiating light, characterized by what at first appears to be almost a haphazard set of spectral lines without relation to one another. But they are related by mathematical laws, and the apparent haphazard character is only the result of our lack of knowledge of how to interpret the results."

He resumed his place at the eyepiece.

"Walter," he said finally, with a twinkle of the eye, "I wish you'd go out and find me a cat."

"A cat?" I repeated.

"Yes—a cat—Felis domesticus, if it sounds better that way—a plain, ordinary cat."

I jammed on my hat and sallied forth on this apparently ridiculous mission.

Several belated passers-by and a policeman watched me as though I were a housebreaker, and I felt like a fool, but at last, by perseverance and tact, I managed to capture a fairly good specimen of the species, and carried it in my arms to the laboratory without an undue number of scratches.

In my absence, Craig had set to work on a peculiar apparatus, as though he were distilling something from several of the other cigarette stubs.

I placed the cat in a basket and watched Craig. It was well along toward morning when he obtained in a test-tube a few drops of a colorless, almost odorless liquid.

I watched him curiously as he picked the cat out of the basket and held it gently in his arms. With a dropper he sucked up a bit of the liquid from the test-tube. Then he let a drop fall into the eye of the cat.

The cat blinked a moment, and I bent over to observe it more closely. It seemed to enlarge, even under the light, as if it were the proverbial cat's eye under a bed.

The cat blinked a moment, and I bent over to observe it more closely.

What did it mean? Was there such a thing as the drug of the evil eye?

"What have you found?" I queried.

"Something very much like the so-called 'weed of madness,' I think," he replied slowly.

"'The weed of madness'?" I repeated.

"Yes; something like that Mexican toloache and the Hindu Datura, which you must have heard about," he continued. "You know the jimson-weed—the Jamestown-weed? It grows almost everywhere in the world, but most thrivingly in the tropics. They are all related in some way, I believe. The jimson-weed on the Pacific coast of the Andes has large white flowers which exhale a faint, repulsive odor. It is a harmless-looking plant with its thick tangle of leaves, a coarse green growth, with trumpet-shaped flowers. But, to one who knows its properties, it is quite too dangerously convenient.

"I think those cigarettes have been doped," he went on. "It isn't toloache that was used. I think it must be some particularly virulent variety of the jimson-weed. The seeds of the stramonium, which is the same thing, contain a higher percentage of poison than the leaves and flowers. Perhaps they were used—I can't say."

He took a drop of the liquid he had isolated and added a drop of nitric acid. Then he evaporated it by gentle heat, and it left a residue slightly yellow. Next, he took from the shelf over his table a bottle marked, "Alcoholic solution, Potassium Hydrate," and let a drop fall on it. Instantly the residue became a beautiful purple, turning rapidly to violet, then to dark red, and finally disappeared.

"Stramonium, all right," he nodded, with satisfaction. "That is known as Vitali's test. Yes; there was stramonium in those cigarettes—Datura stramonium—perhaps a trace of hyoscyamin. They are all, like atropine, mydriatic alkaloids, so-called from the effect on the eye. One one-hundred-thousandth of a grain will affect the cat's eye. You saw how it acted. It is more active than even atropine. Better yet, you remember how Don Luis's eyes looked?"

"How about the señora?" I put in.

"Oh," he answered quickly, "her pupils were normal enough. Didn't you notice that? This concentrated poison which has been used in Mendoza's cigarettes does not kill, at least not outright. It is worse. Slowly it accumulates in the system. It acts on the brain. Of all the dangers to be met with in superstitious countries, these mydriatic alkaloids are among the worst. They offer a chance for crimes of the most fiendish nature—worse than the gun or the stiletto, and with little fear of detection. They produce insanity."

Horrible though the idea was, I could not doubt it in the face of Craig's investigations and what I had already seen. In fact, it was necessary for me only to recall the peculiar sensations I myself had experienced, after taking merely a few puffs of one of Mendoza's cigarettes, in order to be convinced of the possible effect of the insidious poison contained in them.

It was almost dawn before Craig and I left the laboratory after his discovery of the manner of the stramonium poisoning. I was thoroughly tired, though not so much so that my dreams were not haunted by a succession of baleful eyes peering at me from the darkness.

I slept late; but Kennedy was about early at the laboratory, verifying his experiments and checking over his results, carefully endeavoring to isolate any other of the closely related mydriatic alkaloids that might be contained in the noxious fumes of the poisoned tobacco. Though he was already convinced of what was going on, I knew that he considered it a matter of considerable medico-legal importance to be exact, for, if the affair ever came to the stage of securing an indictment, the charge could be sustained only by specific proof.

EARLY in the forenoon, Kennedy left me alone in the laboratory and made a trip down-town where he visited a South American tobacco dealer and placed a rush order for a couple of hundred cigarettes duplicating in shape and quality those which Señor Mendoza preferred.

The package of cigarettes was delivered late in the afternoon. Kennedy had already wrapped up a small package of a powder and filled an atomizer with some liquid. Stowing these things away in his pockets as best he could, with a little vial, which he shoved into his waistcoat pocket, he announced that he was ready, at last, to take an early train to Atlantic Beach.

We dined that night, as Craig had requested, with the Mendozas and Lockwood up in the sitting-room of Don Luis's suite, which overlooked the Boardwalk and the ocean.

Dinner had been ordered but not served, when Craig maneuvered to get a few minutes alone with Inez. Although I could not hear, I gathered that he was outlining at least a part of his plans to her and seeking her cooperation. She seemed to understand and approve, and I really believe that the dinner was the first in a long time that she had enjoyed.

While we were waiting for it, I suddenly became aware that she had contrived to leave Kennedy and myself alone in the sitting-room for a moment. It was evidently part of Craig's plan. Instantly he opened a large case in which Mendoza kept cigarettes and hastily substituted for those in it an equal number of the cigarettes which he had had made.

The dinner itself was more like a family party than a formal dinner, for Kennedy, when he wanted to do so, had a way of ingratiating himself and leading the conversation so that everyone was at his ease. Everything progressed smoothly until we came to the coffee. The señorita poured and, as she raised the coffee-pot, Kennedy called our attention to a long line of colliers just on the edge of the horizon, slowly making their way up the coast.

I was sitting next to the señorita, not particularly interested in colliers at that moment. I saw her hastily draw a little vial from a fold in her dress and pour a bit of yellowish sirupy liquid into the cup which she was preparing for her father.

I saw her hastily draw a little vial from a fold in her dress...

I could not help looking at her quickly. She saw me, then raised her finger to her lips with an explanatory glance at Kennedy, who was keeping the others interested in the colliers. Instantly I recognized the little vial that Kennedy had shoved into his vest pocket.

More coffee and innumerable cigarettes followed. I did my best to aid in the conversation, but my real interest was centered on Don Luis himself.

Was it a fact or was it merely imagination? He appeared quite different. The pupils of his eyes did not seem to be quite so dilated as they had been the night before. Even his heart action appeared to be more normal. I think the señorita noticed it, too.

Dinner over and darkness cutting off the magnificent sweep of ocean view, Inez suggested that we go down to the concert. It was the first time that Kennedy had not seemed to fall in with any of her suggestions, but I knew that that, too, must be part of his plan.

"If you will pardon us," he excused, "Mr. Jameson and I have some friends over at Stillson Hall whom we have promised to run in to see. I think this would be a good opportunity. We'll rejoin you—in the alcove where we were last night, if possible."

We left them at the elevator, but instead of leaving the Inn, Kennedy edged his way around into the shadow of a doorway where we could watch. Fortunately, the señorita managed to get the same settee in the corner which we had occupied the night before.

A moment later, I caught a glimpse of a familiar face at the long window opening on the veranda. Señora de Moche and her son had drawn up chairs, just outside.

They had not seen us and, as far as we knew, had no reason to suspect that we were about. As we watched the two groups, I could not fail to note that the change in Don Luis was really marked. There was none of the wildness in his conversation that there had been. Once, he even met the keen eye of the señora, but it did not seem to have the effect it had previously had.

"What was it you had the señorita drop into his coffee?" I asked Craig.

"You saw that?" he smiled. "It was pilocarpin, made from jaborandi, a plant found largely in Brazil, one of the antidotes for stramonium poisoning. It doesn't work with everyone. But it seems to have done so with Mendoza. Besides, the caffeine in the coffee probably aided the pilocarpin." Kennedy did not take his eyes off the two groups as he talked. "I've got at the case from a brand-new angle, I think," he added. "Unless I am mistaken, when the criminal sees Don Luis getting better, it will mean another attempt to substitute more cigarettes doped with that drug."

Satisfied so far with the play he was staging, Kennedy moved over to the hotel desk and, after a quiet conference with the head clerk, found out that the room next to the suite of the Mendozas was empty. The clerk gave him several keys, and I followed Craig into the elevator. We rode up to the eighth floor again.

The halls were deserted now, and we entered the room next to the Mendozas without being observed. It was a simple matter after that to open a rather heavy door that communicated between the two suites.

Instead of switching on the light, Kennedy first looked about carefully until he was assured that no one was there. Quickly he sprinkled the floor from the hall door to the table on which the case of cigarettes lay with some of the powder which I had seen him wrap up in the laboratory before we left. Then with the atomizer, he sprayed over it something that had a pungent, familiar odor, walking backward from the hall door as he did so.

"Don't you want more light?" I asked, starting to cross to a window to raise a shade to let the moonlight stream in.

"Don't walk on it, Walter," he whispered, pushing me back. "First, I sprinkled some powdered iodine and then ammonia enough to moisten it. It evaporates quickly, leaving what I call my anti-burglar powder."

He had finished his work, and now the evening wind was blowing away the slight fumes that had risen. For a few moments he left the door into the next room open to clear away the odor, then quietly closed it.

In the darkness we settled ourselves, now, for a vigil that was to last we knew not how long. Neither of us spoke.

Slowly the time passed. Would anyone take advantage of the opportunity to tamper with that box of cigarettes on Mendoza's table?

Once or twice we heard the elevator door clang, and waited expectantly, but nothing happened. I began to wonder whether, if some one had a pass-key to the Mendoza suite, we could hear him enter. The outside hall was thickly carpeted and deadened every footfall if one exercised only reasonable caution.

"Don't you think we might leave the door ajar a little?" I suggested anxiously.

"Sh!" was Kennedy's only comment.

In the darkness and silence, I fell to reviewing the weird succession of events which had filled the past two days. I am not by nature superstitious, but in the darkness I could well imagine a staring succession of eyes, beginning with the dilated pupils of Don Luis and always ending with those remarkable piercing black eyes of the Indian woman with the melancholy-visaged son. Suddenly I heard in the next room what sounded like little explosions, as though some one were treading on match-heads.

"My burglar powder," muttered Craig, in a hoarse whisper. "Every step, even those of a mouse running across, sets it off!"

He rose quickly and threw open the door into the Mendoza suite. I sprang through after him. There, in the shadows, I saw a dark form starting back in retreat. But it was too late.

In the dim light of the little explosions, I caught a glimpse of a face—the face of the person who had been craftily working on the superstition of Don Luis, now that his influence had got from the government the precious concession, working with the dread drug to drive him insane and thus capture both Mendoza's share of the fortune as well as that of his daughter, well knowing that suspicion would rest on the jealous Indian woman with the wonderful eyes whose brother had already been driven insane and whose son Inez Mendoza really loved better than himself—the soldier of fortune, Lockwood.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.