RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Cosmopolitan, May 1915, with "The Sixth Sense"

What is the sixth sense? Not one that has come into the possession of the human race through slow evolution but one that Craig Kennedy, with his supreme knowledge of new scientific principles and implements, endows himself with when he finds himself in the most terrifying and hopeless position of his eventful career. You will readily believe that the preservation of his life is not the uppermost thing in Craig's mind when you consider the probable international consequences of the plot he has discovered, should its author succeed in carrying it out.

"I SUPPOSE you have read in the papers of the mysterious burning of our country house at Oceanhurst, on the south shore of Long Island?" It had been about the middle of the afternoon that a huge automobile of the latest design drew up at Kennedy's laboratory and a stylishly dressed woman, accompanied by a very attentive young man, alighted. They had entered, and the man, with a deep bow, presented two cards bearing the names of the Count and Countess Alessandro Rovigno.

Julia Rovigno, I knew, was the daughter of Roger Gaskell, the retired banker. She had recently married Count Rovigno, a young foreigner whose family had large shipping interests in America and at Trieste, on the Adriatic.

"Yes, indeed; I have read about it," nodded Craig.

"You see," she hurried on, a little nervously, "it was a wedding-present to us from my father."

"Giulia," put in the young man quickly, giving her name an accent that was not, however, quite Italian, "thinks the fire was started by an incendiary."

Rovigno was a tall, rather boyish-looking man of thirty-two or thirty-three, with light-brown hair, light-brown beard, and mustache. His eyes and forehead spoke of intelligence; but I had never heard that he cared much about practical business affairs. In fact, to American society, Rovigno was known chiefly as one of the most daring of motor-boat enthusiasts.

"It may have been the work of an incendiary," he continued thoughtfully, "or it may not; I don't know. But there has been an epidemic of fires among the large houses out on Long Island lately."

I nodded to Kennedy, for I had myself compiled a list for the Star, which showed that considerably over a million dollars' worth of show places had been destroyed.

"At any rate," added the countess, "we are burned out, and are staying in town now—at my father's house. I wish you would come around there. Perhaps father can help you. He knows all about the country out that way, for his own place isn't a quarter of a mile away."

"I shall be glad to drop around if I can be any assistance," agreed Kennedy, as the young couple left us.

The Rovignos had scarcely gone when a woman appeared at the laboratory door. She was well dressed, pretty, but looked pale and haggard.

"My name is Mrs. Bettina Petzka," she began, singling out Kennedy. "You do not know me; but my husband, Nikola, was one of the first students you taught, Professor."

"Yes, yes; I recall him very well," replied Craig. "He was a brilliant student, too—very promising. What can I do for you?"

"Why, Professor Kennedy," she cried, no longer able to control her feelings, "he has disappeared!"

"Why, Professor Kennedy," she cried, no longer

able to control her feelings, "he has disappeared!"

"What line of work had he taken up?" asked Craig, interested.

"He was a wireless operator—had been employed on a liner that runs to the Adriatic from New York. But he was out of work. Some one has told me that he thought he saw Nikola in Hoboken, around the docks where a number of the liners that go to blockaded ports are laid up waiting the end of the war." She paused.

"I see," remarked Kennedy, pursing up his lips thoughtfully. "Your husband was not a reservist of any of the countries at war, was he?"

"No; he was, first of all, a scientist. I don't think he had any interest in the war—at least, he never talked much about it."

"I know," persisted Craig; "but had he taken out his naturalization papers here?"

"He had applied for them."

"When did he disappear?"

"I haven't seen him for two nights," she sobbed.

It flashed over me that it was now two nights since the fire that had burned Rovigno's house, although there was no reason for connecting the events. The young woman was plainly wild with anxiety.

"Oh, can't you help me find Nikola?" she pleaded.

"I'll try my best," reassured Kennedy, taking down on a card her address, and bowing her out.

IT was late in the afternoon before we had an opportunity to call at the Gaskell town house, where the Rovignos were staying. The count was not at home, but the countess welcomed us and led us directly into a large library.

"I'd like to have you meet my father," she introduced. "Father, this is Professor Kennedy, whom Alex and I have engaged to look into the burning of our house."

Old Roger Gaskell received us, I thought, with a curious mixture of restraint and eagerness.

"I hope you'll excuse me," said the countess, a moment later. "I really must dress for dinner. But I think I've told you all I can. I wanted you to talk to my father."

"I've heard of the epidemic of fires from my friend Mr. Jameson, here, on the Star," remarked Kennedy, when we were alone. "Some, I understand, have attributed the fires to incendiaries; others have said they were the work of disgruntled servants; others, of an architect or contractor who hasn't shared in the work and thinks he may later. I've even heard it said that an insurance man may be responsible—hoping to get new business, you know."

Gaskell looked at us keenly. Then he rose and approached us, raising his finger as though cautioning silence.

"Do you know," he whispered, so faintly that it was almost lost, "sometimes I think there is a plot against me?"

"Against you?" whispered back Kennedy. "Why, what do you mean?"

"I can't tell you—here," he replied; "but I believe there are detectaphones hidden about this house!"

"Have you searched?" asked Kennedy keenly.

"Yes; but I've found nothing. I've gone over all the furniture and such things. Still, they might be inside the walls."

Kennedy nodded.

"Could you discover them if they were?" asked Gaskell.

"I think I could," replied Craig confidently.

"Then there's another peculiar thing," resumed Gaskell, a little more freely but still whispering: "I suppose you know that I have a country estate not far from my daughter's." He paused. "Of course I know," he went on, watching Kennedy's face, "that sparks are sometimes struck by horses' shoes when they hit stones. But the shoes of my horses, for instance, have been giving forth sparks even in the stable out there lately. My groom called my attention to it, and I saw it myself." He continued looking searchingly at Kennedy. "You are a scientist," he said, at length. "Can you tell how this can be possible?"

Kennedy was thinking deeply.

"I can't offhand," he replied frankly; "but I should like to have a chance to investigate."

"There may be some connection with the fire," hinted Gaskell, as he accompanied us to the door.

At our own apartment, when we returned, we found our friend Burke, of the secret service, waiting for us.

"Just had a hurry-call to come to New York," he explained, "and thought I'd like to drop in on you first."

"What's the trouble?" asked Kennedy.

"Why, there's been a mysterious yacht lurking about the mouth of the harbor for several days, and they want to look into it."

"Whose yacht do they think it is?"

"They don't know; but it is said to resemble one that belongs to a man named Gaskell."

"Gaskell?" repeated Craig, turning suddenly.

"Yes, the Furious, a fast floating palace, one of these new power yachts, run by a gas engine—built for speed. Why, do you know anything about it?"

Kennedy said nothing.

"The revenue cutter Uncas has been assigned to me," went on Burke. "If you have nothing better to do, I'd like to have you give me a hand in the case. You might find it a little different from the ordinary run."

"I shall be glad to go with you," replied Craig cordially. "Only, just now I've got a particular case of my own. I'll see you to-morrow at the custom-house, though, if I can."

"Good!" exclaimed Burke. "I don't think either of you, particularly Jameson, will regret it. It promises to be a good story."

BURKE had scarcely left us when Kennedy decided on his next move. We went directly over to the Long Island Railroad station and caught the next train out to Oceanhurst, not a long run from the city.

Thus, early in the evening, Kennedy was able to begin, under cover, his investigation of the neighborhood of the Rovigno and Gaskell houses.

We entered the Gaskell estate and looked it over as we made our way toward the stable to find the groom. Out on the bay we could see the Furious at anchor. Nearer inshore were a couple of Count Rovigno's speedy racing motor-boats. Along the shore, we saw a basin for yachts, capable, even, of holding the Furious.

The groom proved to be a rather dull-witted fellow, and left us pretty much to our own devices.

"Ya-as—sparks—I saw 'em," he drawled, in answer to Kennedy's question. "So did Mr. Gaskell. Naw; I don't know nawthin' about 'em."

He had lumbered out into another part of the stable when I heard a low exclamation from Craig.

"Look, Walter!"

I did look—in amazement. There were, indeed, little sparks—in fact, a small burst of them in all directions where there were metal surfaces in close proximity.

Kennedy had brought along with him a strange instrument, and he was now looking attentively at it.

"What is that?" I asked.

"The bolometer," he replied, "invented by Professor Langley."

"And what does it do?"

"Detects waves," he replied, "rays that are invisible to the eye. For instance, just now it tells me that shooting through the darkness are invisible waves, perhaps infrared rays."

He paused, and I looked at him inquiringly.

"You know," he explained, "the infrared rays are closer to the heat rays than those of the upper end of the spectrum and beyond the ultra-violet rays, with which we have already had some experience." Kennedy continued to look at his bolometer. "Yes," he remarked thoughtfully, half to himself; "somewhere around here there is a generator of infra-red rays and a projector of those rays. It reminds me of those so-called F rays of Ulivi—or, at least, of a very powerful wireless."

I was startled at the speculations that his words conjured up in my mind. Was the "evil eye" of superstition a scientific fact? Was there a baneful beam that could be directed at will—one that could not be seen or felt until it worked its havoc? Was there a power that steel walls could not hold, which, in fact, was the more surely transmitted by them?

Somehow, the fact of the strange disappearance of Petzka, the wireless operator, kept bobbing up in my mind. I could not help wondering whether,- perhaps, he had found this strange power and was using it for some nefarious purpose. Could it have been Petzka who was responsible for the fires? But why? I could not figure it out.

EARLY the next morning we called at the Gaskell town house again. Kennedy had brought with him a small piece of apparatus which seemed to consist of two sets of coils placed on the ends of a magnet-bar. To them was attached a long, flexible wire which he screwed into an electric-light bulb-socket. Then he placed a peculiar, telephone-like apparatus, attached to the other end, to his ears. He adjusted the magnets and carried the thing carefully about the room.

At one point, he stopped and moved the thing vertically up along the wall.

"That's a gas-pipe," he said simply.

"What's the instrument?" I asked.

"A new apparatus for finding pipes electrically, which, I think, can be just as well applied to finding other things concealed in walls under plaster and paper." He paused to adjust the thing. "This electrical method," he went on, "is a special application of well-known induction-balance principles. You see, one set of coils receives an alternating or vibrating current; the other is connected with this telephone. First, I established a balance so that there was no sound in the telephone." He moved the thing about. "Now, when the device comes near metal piping, for example, or a wire, the balance is disturbed, and I hear a sound. That was the gas-pipe. It is easy to find its exact location. Hello!"

He paused again in a corner, back of Gaskell's desk, and appeared to be listening intently. A moment later he was ruthlessly breaking through the plaster of the beautifully decorated wall.

Sure enough, in there was a detectaphone, concealed only a fraction of an inch beneath the paper, with the wires leading down inside the partition in the direction of the cellar. Craig ripped the little mechanical eavesdropper out, wires and all, but he did not disconnect the wires yet.

We traced it out, and down into the cellar the wires led directly, and then across, through a small opening in the foundations, into the cellar of the next-door apartment-house, ending in a bin or storeroom.

In itself, the thing, so far, gave no clue as to who was using it or the purpose for which it had been installed. But it was strange.

"Some one was evidently trying to get something from you, Mr. Gaskell," remarked Craig pointedly, after we returned to the Gaskell library. "Why do you suppose he went to all that trouble?"

Gaskell shrugged his shoulders and averted his eyes.

"I've heard of a yacht outside New York harbor," added Craig casually.

"A yacht?"

"Yes," he said nonchalantly; "the Furious."

Gaskell met Kennedy's eye and looked at him as though Craig had some occult power of divination. Then he moved over closer to us.

"Is that detectaphone thing out of business now?" he asked hoarsely.

"Yes."

"Absolutely?"

"Absolutely."

Gaskell leaned over.

"Then I don't mind telling you, Professor Kennedy," he said, in a low tone, "that I am letting a friend of mine from London use that yacht to supply the Allies' war-ships in the Atlantic with news, supplies, and ammunition, such as can be carried."

"I am letting a friend of mine from London use that

yacht to supply the Allies' war-ships in the Atlantic."

Kennedy looked at him keenly, but for some moments did not answer. I knew he was debating on how he might ethically dovetail this with Burke's case.

"Some one is trying to find out, by eavesdropping, just what your plans are, then," remarked Craig thoughtfully, with a significant tap on the detectaphone.

A moment later, he turned his back to us and knelt down. He seemed to be wrapping the detectaphone up in a small package which he put in his pocket, and closing the hole in the wall as best he could where he had ripped the paper.

"All I ask of you," concluded Gaskell, as we left, a few minutes later, "is to keep your hands off that phase of things. Find the incendiary—yes; but this other matter that you have forced out of me—well— hands off!"

ON our way down-town to keep the appointment made with Burke the night before, Kennedy stopped at the laboratory to get a heavy parcel, which he carried along. We found Burke waiting for us, impatiently, at the custom-house.

"We've just discovered that the liners over in Hoboken have had steam up for a couple of days," he said excitedly. "Evidently they are waiting to make a break for the ocean—perhaps in concert with a sortie of the fleets over in Europe."

"H-m," mused Kennedy, looking fixedly at Burke; "that complicates matters, doesn't it? We must preserve American neutrality." He thought a moment. "I should like to go aboard the revenue cutter. May I?"

"Surely," agreed Burke.

A few moments later, on the Uncas, Kennedy and Burke engaged in earnest conversation in low tones which I did not overhear. Evidently, Craig was telling him just enough of what he had himself discovered so as to enlist Burke's services.

The captain in charge of the Uncas joined the conversation a few moments later, and then Kennedy took the heavy package down below. For some time he was at work in one of the forward tanks that was full of water, attaching the thing, whatever it was, in such a way that it seemed to form part of the ship's skin.

Another brief talk with Burke and the captain followed, and then the three returned to the deck.

"Oh, by the way," remarked Burke, as he and Kennedy came back to me, "I forgot to tell you that I have had some of my men working on the case, and one of them has just learned that a fellow named Petzka, one of the best wireless operators—a Hungarian or something—has been engaged to go on that yacht."

"Petzka?" I repeated in voluntarily.

"Yes," said Burke, in surprise; "do you know anything about him?"

I turned to Kennedy.

"Not much," replied Craig. "But you can find out about him, I think, through his wife. He used to be one of my students. Here's her address. She's very anxious to hear from him."

Burke took the address, and a little while later we went ashore.

I WAS not surprised when Kennedy proposed, as the next move, to revisit the cellar in the apartment-house next to Gaskell's home. But I was surprised at what he did after we had reached the place.

All along I had supposed that he was planning to wait there in hope of catching the person who had installed the detectaphone. That, of course, was a possibility still. But, in reality, he had another purpose also.

We secreted ourselves in the cellar storeroom, which was in a dark corner, where one might remain unobserved even if the janitor entered the cellar, provided he did not search that part. Kennedy took the receiving headpiece of the detectaphone and placed it over his head, quite as if nothing had happened.

"What's the use of that?" I queried. "You ripped the transmitter out up above."

He smiled quietly.

"While my back was turned toward you, so that you couldn't see," he said, "I slipped the thing back again, only down further, where Gaskell wouldn't be likely to find it, even if he looked. I don't know whether he was frank with us, so I thought I'd try the eavesdropping game myself, in place of the man who put this thing in in the first place, whoever he was."

We took turns listening, but could hear not a sound. Nor did anyone come into the cellar. Thus, a good part of the afternoon passed, apparently fruitless. My patience was thoroughly exhausted when, suddenly, a motion from Craig revived my flagging interest. I waited impatiently for him to tell me what it was that he heard.

"What was it?" I asked, finally, as he pulled the receivers off his head and stood for a moment considering.

"At first I heard the sound of voices," he answered quickly. "One was the voice of a woman, which I recognized. It was the countess. The other was the count.

"'Giulia,' I heard him say, as they entered the room, 'I don't see why you should want to go. It's dangerous. And, besides, it's none of our business if your father allows his yacht to be used for such a purpose.'

"'But I want to go, Alex,' she said. 'I will go. I'm a good sailor. It's father's yacht. He won't care.'

"'But what's the use?' he expostulated. 'Besides—think of the danger! If it was our business, it might be different.'

"'I should think you'd want to go.'

"'Not I. I can get all the excitement I want in a motor-boat race, without risking my precious neck pulling the chestnuts out of the fire for some one else.'

"'Well, I want the adventure,' she persisted.

"'But, Giulia, if you go to-night, think of the risk!'

"That was the last I heard as they left the room, still arguing. Evidently, some one is going to pull off something to-night."

IT did not take Kennedy long to make up his mind what to do next. He left the cellar hurriedly, and, in the laboratory, hastily fixed up a second heavy and bulky package similar to that which he had taken down to the revenue cutter earlier in the day, making it into two parcels so as to distribute the burden between us.

That night, we journeyed out to Oceanhurst again. Avoiding the regular road, we made our way from the station to the Gaskell place by a roundabout path, and it was quite dark by the time we got there.

As we approached the basin, we saw that there were several men about. They appeared to be on guard, but since Oceanhurst, at that season, was pretty well deserted and the Gaskell estate was out of the town, they were not especially vigilant

Dark and grim, with only one light showing weakly, lay the yacht, having been run into the basin now. A hawser had been stretched across the mouth of the basin. Outside was a little tender, while a searchlight was playing over the water all the time. Evidently, whatever interference was feared was expected from the water rather than from the land.

We slunk into the shadow of a row of bath-houses, in order to get our bearings. On the opposite side from the road that led down from the house, it was not so likely that anyone would suspect that interlopers were hiding there. Still, they were not neglecting that side of the basin, at least in a perfunctory sort of way.

Kennedy drew me back deeper into the shadow at the sound of footsteps on the board walk leading to the front of the bathhouses. From our hiding-place, we could now hear two voices, apparently of sailors.

"Do you know the new wireless operator who goes with us to-night?" asked one.

"No; they've been very careful of him. I guess they were afraid that some one might get wise. But there couldn't very well be any leak there. One of those Englishmen has been with him every minute since he was engaged."

"They say he's pretty good. Who is he?"

"A Servian, he says, and his name sounds as if it might be so."

The voices trailed off. It was only a scrap of conversation, but Kennedy had not missed a word of it.

"That means Petzka," he nodded to me.

"What is he—a Hungarian or a Servian?" I asked quickly.

Kennedy had craned his neck out beyond the corner of the bath-houses and was looking at the Furious in the basin.

"Come on, Walter," he whispered, not taking time to answer my question; "those fellows have gone. There's no one at all on this side of the basin, and I just saw the men on deck go up the gangplank to the boat-house. They can't do any more than put us off, anyhow."

He had watched his chance well. As quickly as we could, burdened down by our two heavy packages, we managed to slip across the board walk to the piling that formed that side of the basin. The Furious had swung over with the tide nearer our side than the other. It was a daring leap, but Craig made it as lightly as a cat, landing on the deck. I passed over the packages and followed.

Kennedy scarcely paused to glance about. He had chosen a moment when no one was looking, and bending down under the weight of the packages, we dodged back of a cabin. A dim light shining into the hold told us that no one was there, and we dived down. It was the work of a moment to secrete ourselves in the blank darkness aft, behind a pile of boxes.

A noise startled us. Some one was coming down the steep, ladder-like stairs. A moment later, we heard another noise. There were two persons moving about among the boxes. From our hiding-place we could overhear them talking in hoarse whispers, but could not see them.

"Where did you put them?" asked a voice.

"In every package of explosives, and in as many of the boxes of canned goods as I had time."

I looked at Kennedy, wide-eyed. Was there treachery in the crew? He was leaning forward as much as our cramped quarters would permit, so as not to miss a word that was uttered.

"All right." said the other voice. "No one suspects?"

"No; but the secret service has been pretty busy. They suspect something— but not this."

"Good! You are sure that you can detonate them when the time comes?"

"Positive. Everything is working fine.

"I am letting a friend of mine from London use that yacht to supply the Allies' warships in the Atlantic. I've done my part of it. Changing wireless operators gave me just the chance I wanted."

"All right. I guess I'll go now."

"Remember the signal. As soon as the things are detonated, I will get off some way, by wireless, the S O S—as if it came from the fleet, you understand."

"Yes; that will be the signal for the dash. Good luck! I'm going ashore now."

As they passed up the ladder, I could no longer restrain myself.

"Craig," I cried, "this is devilish!"

I thought I saw it all now. In the cases of goods on the Furious were some terrible infernal machines which had been hidden, to be detonated by these deadly rays of wireless.

Kennedy was busy, working quickly, putting together the parts he had taken from the two packages we had carried.

As I watched him, I realized that the burning of the Rovigno house was not the action of an incendiary after all. It had been done by these deadly rays, probably by mere accident.

As nearly as I could make it out, there was a counterplot against the Furious. Somewhere was an infernal workshop, possibly hedged about by doors of steel which ordinary force would find hard to penetrate, but from which, any moment, this super-criminal might send out his deadly power.

The more I considered it, while Kennedy worked, the more uncanny it seemed. This man had rendered the mere possession of explosives more dangerous to the possessor than to the enemy. Archimedes had been outdone!

The problem before us now was not only the preservation of American neutrality but the actual safety of life.

Through the open hatch I could now hear voices on the deck. One was that of a woman, which I recognized quickly. It was Julia Rovigno.

"I'll be just as quiet as a mouse," she was saying. "I'll stay in the cabin—I won't be in the way."

I could not hear the man's voice in reply, but it did not sound like Rovigno's. It was rather like Gaskell's.

Still, we had heard enough to know that Julia Rovigno was on the yacht, had insisted on going on the expedition for the excitement of the thing, just as we had heard over the detectaphone.

"Hadn't we better warn her?" I asked Craig, who had paused in his work at the sound of voices.

Before he could answer we were plunged in sudden darkness. Some one had switched out the light that had been shining down through the hatchway. Before we knew it, the opening to the hatchway had been closed. Kennedy groped about for a light, stumbling over boxes and bags.

"For heaven's sake, Craig," I entreated, "be careful! Those packages are full of the devilish things!" He said nothing.

At least we had a little more freedom to move, and I managed to find my way over to a little round port-hole and open it.

As I looked out, I almost fainted at the realization. The Furious was under way! We were locked in the hold—virtual prisoners—our only company those dastardly infernal machines, whose very nature we did not know. Helplessly I gazed around me. There seemed to be only this one porthole.

Why had Kennedy not foreseen this risk? I glanced at him. He had found an electric light, connected with the yacht's dynamo, and, before turning it on, closed and covered the port so that it threw no reflection out.

Far from being disconcerted, on the contrary he seemed rather pleased than otherwise at the unexpected turn of events.

As I looked at our scant and cramped quarters, I could see absolutely no way of getting word to anyone off the Furious who might help us.

What Craig was working on I did not know, but if it was some sort of wireless, even if we were able to send a message, what hope was there that it would get past the delicate wireless detector which this criminal must have somewhere near for tapping messages that were being flashed through the air? Had we not heard him say that the signal was to be an S O S sent, as it were, from the fleet far out on the ocean?

I could well have believed that Kennedy could rig up some means of communication. But, if the possessor of this terrible infrared-ray or wireless-wave secret should learn that we, too, knew it, the only result that he would accomplish would be to insure our destruction immediately.

It was a foggy night, and a drizzle had set in. The Furious could not, under such circumstances, make such good speed as she was accustomed to make. Fortunately, also, the waves were not running high. Craig had taken a desperate chance. How would he meet it? I watched him at work, fascinated by our peril.

Finishing as quickly as he could, he put out our sole electric light, unscrewed the bulb, and attached to the socket a wire which he had connected with the instrument over which he had spent so many precious moments.

Through the little port-hole, he cast a peculiar heavy disk, such as I had seen him place so carefully aboard the Uncas.

It sank in the water with a splash, and trailed along beside the yacht, held by a wire submerged perhaps ten or twelve feet.

Kennedy made a final inspection of the thing as well as he could by the light of a match, then pressed a key which seemed to close a circuit. I could feel a dull, metallic vibration.

"What are you doing?" I asked, looking curiously, also, at an arrangement like a microphone which he had placed over his ears.

"It works!" he cried excitedly.

"What works?" I reiterated.

"This Fessenden oscillator," he explained. "It's a system for the employment of sound for submarine signals. I don't know whether you realize it, but great advance has been made recently, since it was suggested to use water instead of air as the medium for transmitting signals. I can't stop to explain this apparatus just now, but it is composed of a ring magnet, a copper tube which lies in an air gap of a magnetic field, and a stationary central armature.

"The copper tube, which has an alternating current induced in it, is attached to solid disks of steel which, in turn, are attached to a steel diaphragm an inch thick. On board the Uncas, I had a chance to make that diaphragm practically a part of the side of the ship. Here, I have had to hang it overboard, with a large water-tight diaphragm attached to the oscillator."

I listened eagerly.

"The same oscillator," he went on, "is used for sending and receiving, for, like the ordinary electric motor, it is also capable of acting as a generator, and a very efficient one, too. All I have to do is to throw a switch in one direction when I want to telegraph or telephone under water, and in the other direction when I want to listen in."

I could scarcely credit what I heard. Craig had circumvented even the spectacular wireless. He was actually talking through water. He had virtually endowed himself with a sixth sense!

I watched him, spellbound. Would he succeed in whatever it was that he was planning? I waited anxiously.

"There's the answer!" he exclaimed, in sudden exultation. "Burke is on the Uncas. He tells me that he went to see Mrs. Petzka, and she is with him—insisted on going when she heard that her husband had been engaged by the Furious." He waited a moment. "You see, Walter," he resumed, "what I am doing is to send out signals by which the Uncas can locate and follow us. She is fast—but, thank heaven!— this yacht has to go slow to-night. Sound travels in water at a velocity of about four thousand feet a second. For instance, I find that I get an echo in about one-twentieth of a second. That is the reflected soundwave from the bottom, and indicates that we are in water of about one hundred feet depth. Then I get another echo in something over two seconds. That is from the waves reflected from the Uncas, which has been hovering about, waiting for something to happen. They can't be much more than a mile and a half away now. I had expected to signal them from the shore—a dock or something of the sort, using this oscillator to get around that fellow's wireless; but we're much better off here."

I looked at him in amazement.

"Surrounded by all this junk that may blow us to kingdom come, any second?" I demanded.

"Burke says steam is still up on all the ships tied up in the harbor so that they can make a dash for it. They are evidently waiting for that SOS signal."

"That's all right," I said, in desperation; "but suppose they blow us up, first?"

"Blow us up, first?" he repeated. "Why, don't you understand? It is not the Furious that they are after. The whole war-fleet that is hanging around in this part of the Atlantic is to be blown up in mid-ocean, as part of the plan to aid the escape of the interned ships from New York."

"Oh," I breathed, with a sigh of relief, "that's it, is it?"

"Yes. We'll get in bad all around if we can't stop it—Burke with the secret service, and ourselves with Gaskell, who doesn't dream that his yacht is being used for the exact opposite of the purpose for which he thinks he has lent it—to say nothing of the mess that our government will have to face for letting these precious schemers play ducks and drakes with our neutrality."

We waited eagerly, Kennedy sending out and receiving the submarine signals, and I peering out anxiously into the almost impenetrable fog.

Suddenly, apparently from nowhere in the shifting mist, lights seemed to loom up. Instead of stopping, however, the Furious put on a sudden burst of reckless speed.

The Uncas was no match for her at that game. Would she escape finally, after all?

A sharp report rang out. The Uncas had sent a shot across our bows, so dangerously close that it snapped one of the cables that braced the mast.

The vibration of our engine slowed and ceased, and we lay idly wallowing in the waves, as the revenue cutter, bearing our friend Burke and help, came up.

A couple of boats put out from the cutter, and in almost no time we could hear the tread of feet and the exchange of harsh words as the government officers swarmed up the ladder to our deck. It was only a moment later that the hatch was broken open and we heard Burke, calling,

"Kennedy—are you and Jameson all right?"

"Right here!" sang out Craig, detaching the oscillator and replacing the electric bulb, which he lighted.

The commotion on deck was too great for anyone to make much of finding us two stowaways. The countess was astonished, however, and, I felt, rather glad to see us at a time when we might possibly exert some influence in her favor, if matters came to a more serious pass.

There was scarcely time for a word. Burke's men were working quickly. They had entered the hold, after a word from Kennedy, and far out into the ocean they were casting the boxes and bags overboard, one at a time, as fast as they could. They worked feverishly, as Burke spurred them on, and I must say that it was with the utmost relief that I saw the things thrown over. The boxes sank, but rose again and floated, bobbing up and down—at least some of them—perhaps a third above water and two-thirds below.

It was not for several minutes that I noticed that with those who had come aboard the Furious from the cutter stood Bettina Petzka. A moment later, she caught sight of Kennedy.

"Where is my husband?" she demanded.

Kennedy had no chance to reply.

Suddenly a series of flashes shattered the darkness. A terrific roar seemed to rise from the very ocean, while a rain of sparks lighted up great spurts of water and then fell back, to perish in the dark waves. The Furious trembled from end to end.

Startled, we looked at each other. But we were all safe. The things had been detonated in the water.

"Only the fact that he would have blown himself up prevented him from blowing up the yacht and all the evidence against him, now that we have discovered his plot!" cried Burke excitedly, dashing down the deck.

Scarcely recovered from our surprise at the explosion and the queer actions of the secret-service man, we rushed after him.

He led the way to the little wireless-room. The door was bolted on the inside, but we managed soon to burst it open.

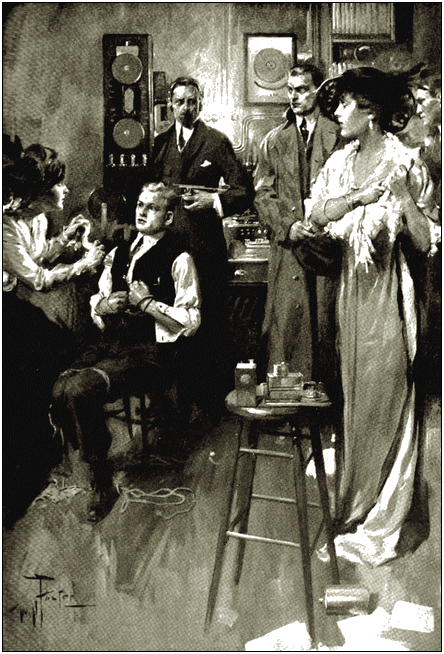

I SHALL never forget the surprise which greeted us. In a chair, bound and gagged, as though he had been overcome only after a struggle, sat Petzka. His wife threw herself frantically on him, tearing at the stout cords that held him.

In a chair, bound and gagged, as though he had been overcome only after

a struggle, sat Petzka. His wife threw herself frantically on him.

"Nikola, what is the matter?" she cried. "What has happened?"

Through his gag, which she had loosened a bit, he made a peculiar, gurgling noise. As nearly as I could make out, he was struggling to say,

"He came in—surprised me—seized me—locked the door."

Julia Rovigno stood rooted to the spot— utterly speechless.

There, surrounded by electric batteries, condensers, projectors, regulators, resonators, reflectors, voltmeters, and ammeters, queer apparatus which he had smuggled secretly on the Furious, before a strange sort of device, with a wireless headgear still over his ears, stood the owner of at least two of the liners of the belligerents which were to have made the dash for the ocean, after he had succeeded, by his new wireless-ray device, in removing the hostile fleet—Count Rovigno himself!

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.