RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Cosmopolitan, March 1914, with "The Radium Robber"

You want to know the latest, of course, but what is the use of being bored to death by dry, scientific theses? "I want to thank Mr. Reeve," writes a subscriber, "for enabling me to keep up to date in scientific progress just by reading an interesting story. Every month I wonder what Craig is going to do next, and always turn to that story first." You can be sure that if anything important in science is discovered, Kennedy won't be long in finding some practical way to use it. This month he has a pretty tough problem to handle, but his skill and knowledge of up-to-the-minute progress help him blaze a way through a rough mystery-tangle.

"MOST ingenious, but, you see, the trouble with that safe

is that it was built to keep radium in—not

cracksmen out," remarked Kennedy, as we stood before a

little safe in the works of the Federal Radium Corporation.

Murray Denison, president of the corporation, had taken Kennedy and myself with him post-haste to Pittsburgh at the first news of what had immediately been called "the great radium robbery."

Of course the newspapers were already full of it. The very novelty of an ultramodern cracksman going off with something worth upward of a couple of hundred thousand dollars—and all contained in a few platinum tubes which could be tucked away in a vest pocket—had something about it powerfully appealing to the imagination.

"Breaking into such a safe as this," added Kennedy, after a cursory examination, "is simple enough, after all."

It was, however, a remarkably ingenious contrivance, about three feet in height and of a weight of perhaps a ton and a half, and all to house something weighing only a few grains.

"But," Denison hastened to explain, "we had to protect the radium not only against burglars but, so to speak, against itself. Radium emanations pass through steel, and experiments have shown that the best metal to contain them is lead. So the difficulty was solved by making a steel outer case enclosing an inside leaden shell, three inches thick."

Kennedy had been toying thoughtfully with the door.

"Then the door, too, had to be contrived so as to prevent any escape of the emanations through joints. It is lathe-turned and circular, a 'dead fit.' By means of a special contrivance, any slight looseness caused by wear and tear of closing can be adjusted. And there is another feature. That is the appliance for preventing the loss of emanation when the door is opened. Two valves have been inserted into the door, and before it is opened, tubes with mercury are passed through, which collect and store the emanation."

"All very nice for the radium," remarked Craig cheerfully. "But the fellow had only to use an electric drill."

"I know that—now," ruefully persisted Denison. "But the safe was designed for us specially. The fellow got into it and got away without leaving a clue."

"Except one, of course," interrupted Kennedy quickly.

Denison looked at him a moment keenly, then said: "Yes—you are right. You mean one which he must bear on himself?"

"Exactly. You can't carry a gram or more of radium bromide long with impunity. The man to look for is one who, in a few days, will have somewhere on his body a burn which will take months to heal."

Kennedy had meanwhile picked up one of the corporation's circulars lying on a desk. He ran his eye down the list of names.

"So Hartley Haughton, the broker, is one of your stockholders," mused Kennedy.

"Not only one, but the one," replied Denison, with obvious pride.

Haughton was a young man who had come recently into his fortune, and he had cut quite a figure in Wall Street.

"You know, I suppose," added Denison, "that he is engaged to Felicie Wood, the daughter of Mrs. Courtney Wood?"

Kennedy did not, but said nothing.

"A most delightful little girl," continued Denison thoughtfully. "I have known Mrs. Wood for some time. She wanted to invest, but I told her frankly that this is, after all, a speculation. We may not be able to swing so big a proposition, but, if not, no one can say we have taken a dollar of money from widows and orphans."

"I should like to see the works," nodded Kennedy approvingly.

"By all means."

THE plant was a row of long, low buildings of brick on

the outskirts of the city, once devoted to the making of vanadium

steel. The ore, as Denison explained, was brought to Pittsburgh

because he had found here, all ready, a factory which could

readily be turned into a plant for the extraction of radium.

"This must be like extracting gold from sea water," remarked Kennedy jocosely, impressed by the size of the plant.

"Except that, after we get through, we have something infinitely more precious than gold," replied Denison, "something which warrants the trouble and outlay. Yes, the fact is that the percentage of radium in all such ores is even less than that of gold in sea water."

"Everything seems to be most carefully guarded," remarked Kennedy, as we concluded our tour of the works.

He had gone over everything in silence, and now we had returned to the safe.

"Yes," he repeated slowly, as if confirming his original impression, "such an amount of radium as was stolen wouldn't occasion immediate discomfort to the thief, I suppose, but, later, no infernal machine could be more dangerous to him."

I pictured to myself the series of fearful works of mischief and terror that might follow—a curse on the thief worse than that of the weirdest curses of the Orient, the danger to the innocent, and the fact that it was an instrument for committing crimes that might defy detection.

"There is nothing more to do here now," he concluded. "I can see nothing for the present except to go back to New York. The telltale burn may not be the only clue, but if the thief is going to profit by his spoils, we shall hear about it best in New York, or by cable from abroad."

OUR hurried departure from New York had not given us a

chance to visit the offices of the Radium Corporation for the

distribution of the salts themselves. They were in a little old

office-building on William Street, scarcely a moment's walk from

the financial district.

"Our head bookkeeper, Miss Wallace, is ill," remarked Denison, when we arrived at the office, "but if there is anything I can do to help you, I shall be glad to do it. We depend on Miss Wallace a great deal."

Kennedy looked about the well-appointed suite curiously.

"Is this another of those radium-safes?" he asked, approaching one similar in appearance to that which had been broken open already.

"Yes, only a little larger."

"How much is in it?"

"Most of our supply. I should say about two and a half grams."

"It is of the same construction, I presume," pursued Kennedy. "I wonder whether the lead lining fits closely to the steel?"

"I think not," considered Denison. "As I remember, there is a sort of insulating air cushion or something of the sort."

He was quite eager to show us about. In fact, ever since he had hustled us out to the scene of the robbery, his high, nervous tension had given us scarcely a moment's rest. He was one of those nervous, active little men, a born salesman, whether of ribbons or of radium.

"We have just gone into furnishing radium water," he went on, bustling about and patting a little glass tank.

I looked closely and could see that the water glowed in the dark.

"The apparatus for the treatment," he continued, "consists of two glass-and-porcelain receptacles. Inside the larger receptacle is placed the smaller, which contains a tiny quantity of radium. Into the larger receptacle is poured about a gallon of filtered water. The emanation from that little speck of radium is powerful enough to penetrate its porcelain holder and charge the water with its curative properties. From a tap at the bottom of the tank, the patient draws the number of glasses of water a day prescribed. For such purposes the emanation, within a day or two of being collected, is as good as radium itself. Why, this water is five thousand times as radioactive as the most radioactive natural spring water."

"You must have control of a comparatively large amount of the metal," suggested Kennedy.

"We are, I believe, the largest holders of radium in the world," he answered. "I have estimated that, all told, there are not much more than ten grams, of which Madame Curie has perhaps three, while Sir Ernest Cassel, of London, is the holder of perhaps as much. We have nearly four grams."

Kennedy nodded and continued to look about.

"The Radium Corporation," went on Denison, "has several large deposits of radioactive ore in Utah, in what is known as the Poor Little Rich Valley, a valley so named because from being about the barrenest and most unproductive mineral or agricultural hole in the hills, the sudden discovery of the radioactive deposits has made it almost priceless."

He had entered a private office and was looking over some mail.

"Look at this," he called, picking up a clipping from a newspaper which had been laid there for his attention. "You see, we have them aroused."

We read the clipping together hastily:

PLAN TO CAPTURE WORLD'S RADIUM

London—Plans are being matured to form a large corporation for the monopoly of the existing and future supply of radium throughout the world. The company is to be called Universal Radium, Limited, and the capital of ten million dollars will be offered for public subscription at par simultaneously in London, Paris, Vienna, Berlin, and New York.

The company's business will be to acquire mines and deposits of radioactive substances as well as the control of patents and processes connected with the production of radium. The outspoken purpose of the new company is to obtain a world-wide monopoly and maintain the price.

"Ah—a competitor," commented Kennedy, handing back the clipping.

"Yes. You know radium salts used always to come from Europe. Now we are getting ready to do some exporting ourselves. Say," he added excitedly, "there's an idea, possibly, in that."

"How?" queried Craig.

"Why, since we should be the principal competitors of the Austrian mines, greater than the mines of Cornwall, why couldn't this robbery have been due to the machinations of these schemers? Why, to my mind, the United States will have to be reckoned with, first, in cornering the market. This is the point, Kennedy: Would those people who seem to be trying to extend their new company all over the world stop at anything in order to cripple us at the start?"

HOW much longer Denison would have rattled on in his

effort to explain the robbery, I do not know. The telephone-bell

rang, and a reporter from the Record, who had just read

my own story in the Star, asked for an interview. I knew

that it would be only a question of minutes, now, before the

other men were wearing a path out on the stairs, and we managed

to get away before the onrush began.

"Walter," said Kennedy, as soon as we had reached the street. "I want to get in touch with Halsey Haughton. How can I?"

I could think of nothing better at that moment than to inquire at the Star's Wall Street office, which happened to be around the corner. I knew the men down there intimately, and a few minutes later we were in the office.

They were as glad to see me as I was to see them, for the story of the robbery had interested the financial district perhaps more than any other.

"Where can I find Halsey Haughton at this hour?" I asked.

"Say!" exclaimed one of the men, "what's the matter? There have been all kinds of rumors in the Street about him, to-day. Did you know he was ill?"

"Where can I find Halsey Haughton at this hour?" I asked.

"Say!" exclaimed one of the men, "what's the matter?"

"No," I answered. "Where is he?"

"Out at the home of his fiancée, at Glenclair."

"What's the matter?" I persisted.

"That's just it. No one seems to know. They say—well—they say he has a cancer."

Halsey Haughton suffering from cancer! It was such an uncommon thing to hear of in a young man that I looked up quickly in surprise. Then all at once it flashed over me that Denison and Kennedy had discussed the matter of burns from the stolen radium. Might not this be, instead of cancer, a radium burn?

Kennedy signaled to me with a quick glance not to say too much, and a few minutes later we were bound for the pretty little New Jersey suburb of Glenclair.

IT was late when we arrived, yet Kennedy had no

hesitation in calling at the quaint home of Mrs. Courtney Wood,

on Woodridge Avenue.

Mrs. Wood, a well-set-up woman of middle age, who had retained her youth and good looks in a remarkable manner, met us in the hall. Briefly, Kennedy explained that we had just come in from Pittsburgh with Mr. Denison, and that it was very important that we should see Haughton at once.

We had hardly told her the object of our visit when a young woman of perhaps twenty-two or -three, a very pretty girl, with all the good looks of her mother and a freshness which only youth can possess, tiptoed quietly downstairs. Her face told plainly that she was deeply worried over the illness of her fiancé.

"Who is it, mother?" she whispered, from the turn of the stairs. "Hartley's door was open when the bell rang, and he thought he heard something said about the Pittsburgh affair."

Though she had whispered, it had not been for the purpose of concealing anything from us, but rather that the keen ears of her patient might not catch the words. She cast an inquiring glance at us.

"Yes," responded Kennedy, in answer to her look, modulating his tone. "We have just left Mr. Denison at the office. Might we see Mr. Haughton for a minute?"

The two women appeared to consult for a moment.

The two women appeared to consult for a moment.

"Felicie," called a rather nervous voice from the second floor, "is it some one from the company?"

"Just a moment, Hartley," she answered, then, lower to her mother, added, "I don't think it can do any harm."

"You remember the doctor's orders, my dear." Again the voice called her.

"Hang the doctor's orders!" the girl exclaimed, with an air of masculinity. "It can't be half so bad as to have him worry. Will you promise not to stay long? We expect Doctor Bryant in a few moments."

We followed her upstairs and into Haughton's room, where he was lying in bed, propped up by pillows. Haughton certainly was ill. There was no mistake about that. He was a tall, gaunt man, with an air about him that snowed that he found illness very irksome. Around his neck was a bandage, and some adhesive tape at the back showed that a plaster of some sort had been placed there.

As we entered, his eyes traveled restlessly from the face of the girl to our own in an inquiring manner. He stretched out a nervous hand to us, while Kennedy explained how we had become associated with the case and what we had seen already.

"And there is not a clue?" he repeated, as Craig finished.

"Nothing tangible yet," reiterated Kennedy. "I suppose you have heard of this rumor from London of a trust that is going into the radium field internationally?"

"Yes," he answered, "that is the thing you read to me in the morning papers, you remember, Felicie. Denison and I have heard such rumors before. If it is a fight, then we shall give them a fight. They can't hold us up, if Denison is right in thinking that they are at the bottom of this—this robbery."

"Then you think he may be right?"

Haughton glanced nervously from Kennedy to me.

"Really," he answered, "you see how impossible it is for me to have an opinion? You and Denison have been over the ground. You know much more about it than I do."

Again we heard the bell downstairs, and a moment later a cheery voice, as Mrs. Wood met some one down in the hall, asked, "How is the patient to-night?"

We could not catch the reply.

"Doctor Bryant, my physician," put in Haughton. "Don't go. Hello, Doctor! Why, I'm much the same to-night, thank you."

Doctor Bryant was a bluff, hearty man, with the personal magnetism which goes with the making of a successful physician. He had mounted the stairs quietly but rapidly, evidently prepared to see us.

"Would you mind waiting in this little dressing-room?" asked the doctor, motioning to another, smaller room adjoining.

He had taken from his pocket a little instrument with a dial-face like a watch, which he attached to Haughton's wrist.

"A pocket instrument to measure blood pressure," whispered Craig, as we entered the little room.

While the others were gathered about Haughton, we stood in the next room, out of ear-shot. Kennedy had leaned his elbow on a chiffonier. As he looked about the little room, more from force of habit than because he thought he might discover anything, Kennedy's eye rested on a glass tray, on the top, in which lay some pins, a collar button or two which Haughton had apparently just taken off, and several other little, unimportant articles.

Kennedy bent over to look at the glass tray more closely; a puzzled look crossed his face, and he gathered up the tray and its contents.

"Keep up a good courage," said Doctor Bryant. "You'll come out all right, Haughton." Then, as he left the bedroom, he added to us, "Gentlemen, I hope you will pardon me, but if you could postpone the remainder of your visit until a later day, I am sure you will find it more satisfactory."

There was an air of finality about the doctor, though nothing unpleasant in it.

We followed him down the stairs, and, as we did so, Felicie, who had been waiting in a reception-room, appeared before the portières.

"Doctor Bryant," she appealed, "is he—is he really—so badly?"

The doctor reached down and took one of her hands. "Don't worry, little girl," he encouraged. "We are going to come out all right—all right."

She turned from him to us and, with a bright, forced smile which showed the stuff she was made of, bade us good-night.

OUTSIDE, the doctor, apparently relenting that he had

virtually forced us out, paused before his car. "Are you going

down toward the station? Yes? I should be glad to drive you

there."

Kennedy climbed into the front seat, leaving me in the rear, where the wind wafted me their conversation.

"What seems to be the trouble?" asked Craig.

"Very high blood pressure, for one thing."

"For which the latest thing is the radium-water cure, I suppose?" ventured Kennedy.

"Well, radioactive water is one cure for hardening of the arteries. But I didn't say he had hardening of the arteries. Still, he is taking the water with good results. You are from the company?"

Kennedy nodded.

"It was the radium water that first interested him in it. Why, we found a pressure of two hundred and thirty millimeters of mercury, which is frightful, and we have brought it down to a hundred and fifty—not far from normal."

"Still, that could have nothing to do with the sore on his neck," hazarded Kennedy. The doctor looked at him quickly, then ahead at the path of light which his motor shed on the road.

He said nothing, but I fancied that even he felt there was something strange in his silence over the new complication. He did not give Kennedy a chance to ask whether there were any other such sores.

"At any rate," he said, as he throttled down his engine before the Glenclair station, "that girl needn't worry."

There was evidently no use in trying to extract anything further from him. We thanked him and turned to the ticket window to see how long we should have to wait.

"Either that doctor doesn't know what he is talking about, or he is concealing something," remarked Craig, as we paced up and down the platform. "I am inclined to read the enigma in the latter way."

NOTHING more passed between us during the journey back,

and we hurried directly to the laboratory, late as it was.

Kennedy had evidently been revolving something over and over in

his mind, for the moment he had switched on the light, he

unlocked one of his cabinets and took from it an instrument,

placing it on a table before him.

It was a peculiar-looking instrument, like a round, glass electric battery with a cylinder atop, smaller and sticking up like a safety-valve. On that was an arm, a dial, and a lens fixed in such a way as to read the dial. I could not see what else the rather complicated little apparatus consisted of, but inside, when Kennedy brought near it the pole of a static electrical machine, two delicate thin leaves of gold seemed to fly wide apart.

Kennedy had brought the glass tray near the thing. Instantly the leaves collapsed, and he made a reading through the lens.

"What is it?" I asked.

"A radioscope," he replied, still observing the scale. "Really a very sensitive gold-leaf electroscope, devised by one of the students of Madame Curie. This method of detection is far more sensitive even than the spectroscope."

"What does it mean when the leaves collapse?" I asked.

"Radium has been near that tray," he answered. "It is radioactive. I suspected it first when I saw that violet color. That is what radium does to that kind of glass. You sec, if radium exists in a gram of inactive matter only to the extent of one in ten thousand million parts, its presence can readily be detected by this radioscope. Ordinarily the air between the gold leaves is insulating. Bringing something radioactive near them renders the air a good conductor, and the leaves fall."

"Wonderful," I exclaimed, marveling at the delicacy of it.

"Take radium water," he went on, "sufficiently impregnated with radium emanations to be luminous in the dark, like that water of Denison's. It would do the same. In fact, all mineral waters and the so-called curative muds, like fango, are slightly radioactive. There seems to be a little radium everywhere on earth. We are surrounded and permeated by radiations— that soil out there on the campus, the air of this room, all. But," he added contemplatively, "a lot of radium has been near that tray, and recently."

"How about that bandage about Haughton's neck?" I asked suddenly. "Do you think radium could have had anything to do with that?"

"Well, as to burns, there is no particular immediate effect usually, and sometimes even up to two weeks or more, unless the exposure has been long and to a considerable quantity. Of course radium keeps itself always three or four degrees warmer than other things about it constantly. But that isn't what does the harm. It is continually emitting little corpuscles, traveling from twenty to one hundred and thirty thousand miles a second, and these corpuscles blister and corrode the flesh like quick-moving missiles bombarding it. The gravity of such lesions increases with the purity of the radium. For instance, I have known an exposure of half an hour to a comparatively small quantity through a tube, a box, and the clothes to produce a blister fifteen days later. Curie said he wouldn't trust himself in a room with a kilogram of it. It would destroy his eyesight, burn off his skin, and kill him eventually."

He was still fumbling with the glass plate and the various articles on it.

"There's something very peculiar about all this," he muttered, almost to himself.

TIRED by the quick succession of events of the past two

days, I left Kennedy still experimenting in his laboratory and

retired, wondering when the real clue was to develop. Who could

it have been who bore the telltale burn? Was the mark hidden by

the bandage about Haughton's neck the brand of the stolen

tubes?

No answer came to me, and I fell asleep and woke up without a radiation of light on the subject. Kennedy spent the greater part of the day still at his laboratory, performing some every delicate experiments. Finding nothing to do there, I went down to the Star office and spent my time reading the reports that came in from the small army of reporters who had been assigned to run down clues in the case, which was the sensation of the moment.

One thing which uniformly puzzled the newspapers was the illness of Haughton, and his enforced idleness at a time which was of so much importance to the company which he had very largely financed. Then, of course, there was the romantic side of his engagement to Felicie Wood. Just what connection Felicie Wood had with the radium robbery, if any, I was myself quite unable to fathom. Still, that made no difference to the papers. She was pretty, and therefore they published her picture, three columns deep—with Haughton and Denison, who were intimately concerned with the real loss, in little ovals perhaps an inch across.

THE late-afternoon news-editions had gone to press, and I

had given up in despair, determined to go up to the laboratory

and sit around idly, watching Kennedy with his mystifying

experiments, in preference to waiting for him to summon me.

I had scarcely arrived and settled myself to an impatient watch, when an automobile drove up furiously, and Denison himself, very excited, dashed into the laboratory.

"What's the matter?" asked Kennedy, looking up from a test-tube which he had been examining.

"I've had a threat!" ejaculated Denison.

He laid on one of the laboratory tables a letter, without heading and without signature, written in a disguised hand with an evident attempt to simulate the cramped script of a foreign hand.

I know who did the Pittsburgh job. The same party is out to ruin Federal Radium. Remember Pittsburgh, and be prepared!

A Stockholder.

"Well?" demanded Kennedy.

"That can have only one meaning," asserted Denison.

"What is that? " inquired Kennedy.

"Why, another robbery—here in New York, of course."

"But who would do it?" I asked.

"Who?" repeated Denison, "Some one representing that European combine, of course. That is only part of the trust's method—ruin of competitors whom they cannot absorb."

"Then you have refused to go into the combine? You know who is backing it?"

"N-no," admitted Denison reluctantly. "We have only signified our intent to go it alone, as often as anyone has offered to buy us out. No; I do not even know who the people are. They never act in the open. The only hints I have ever received were through perfectly reputable brokers."

"Does Haughton know of this note?" asked Kennedy.

"Yes; I called him up."

"What did he say?"

"He said to disregard it. But—you know what condition he is in. I don't know what to do, whether to surround the office by a squad of detectives or remove the radium to a regular safety-deposit vault, even at the loss of the emanation. Haughton has left it to me."

Suddenly the thought flashed across my mind that perhaps Haughton could act in this disinterested fashion because he had no fear of ruin, either way. Might he not be playing a game with the combination in which he had protected himself, so that he would win, no matter what happened?

"What shall I do?" asked Denison.

"Neither," decided Kennedy.

Denison shook his head. "No," he said; "I shall have some one watch there, anyhow."

DENISON had scarcely gone to arrange for some one to

watch the office that night, when Kennedy, having gathered up his

radioscope and packed into a parcel a few other things from

various cabinets, announced: "Walter, I must see that Miss

Wallace right away. Denison has already given me her address.

Call a cab while I finish clearing up here. I don't like the

looks of this thing."

We found Miss Wallace at a modest boarding-house in an old but still respectable part of the city. She was a very pretty girl, of the slender type, rather a business woman than one given much to amusement. She had been ill and was still ill. That was evident from the solicitous way in which the motherly landlady scrutinized two strange callers.

Kennedy presented a card from Denison, and the girl came down to see us.

"Miss Wallace," began Kennedy, "I know it is almost cruel to trouble you when you are not feeling like office-work, but, since the robbery of the safe at Pittsburgh, there have been threats of a robbery of the New York office."

She started involuntarily.

"Oh," she cried, "why, the loss means ruin to Mr. Denison."

There were genuine tears in her eyes.

"I thought you would be willing to aid us," pursued Kennedy sympathetically. "Now, for one thing, I want to be perfectly sure just how much radium the corporation owns, or rather owned before the robbery."

"The books will show it," she said.

"They will," commented Kennedy. "Then, if you will explain to me briefly just the system you used in keeping account of it, perhaps I need not trouble you any more."

"I'll go down there with you," she answered bravely. "I'm better to-day."

She had risen, but it was evident that she was not as strong as she wished us to think.

"The least I can do is to make it as easy as possible by going in a car," remarked Kennedy, following her into the hall where there was a telephone.

The hallway was perfectly dark, yet, as she preceded us, I could see that the diamond pin which held her collar in the back sparkled as if a lighted candle had been brought near it. I had noticed in the parlor that she wore a handsome tortoise-shell comb set with what I thought were other brilliants, but when I looked I saw, now, that there was not the same sparkle to the comb which held her dark hair in a soft mass. I noticed these little things at the time, not because I thought they had any importance, but merely by chance, wondering at the sparkle of the one diamond which had caught my eye.

"What do you make of her?" I asked, as Kennedy finished telephoning.

"A very charming and capable girl," he answered non-committally.

"Did you notice how that diamond in her neck sparkled?" I asked quickly.

He nodded.

"What makes it?" I pursued.

"Well, you know radium rays will make a diamond fluoresce in the dark."

"Yes," I objected, "but how about those in the comb?"

"Paste, probably," he answered tersely, as we heard the girl's foot on the landing. "The rays won't affect paste."

It was indeed a shame to take advantage of Miss Wallace's loyalty to Denison, but she was so game about it that I knew that only the utmost necessity on Kennedy's part would have prompted him to do it. She had a key to the office, so that it was not necessary to wait for Denison.

Together, she and Kennedy went over the records. It seemed that there were in the safe twenty-five platinum tubes of one hundred milligrams each, and that there had been twelve of the same amount in Pittsburgh. Little as it seemed in weight, it represented a fabulous fortune.

"You have not the combination?" inquired Kennedy.

"No. Only Mr. Denison has that. What are you going to do to protect the safe to-night?" she asked.

"I have a plan," said Kennedy, watching her intently. "Miss Wallace, it was too much to ask you to come down here. You are ill."

She was indeed quite pale, as if the excitement had overtaxed her strength.

"No indeed," she persisted. Then, feeling her own weakness, she moved toward the door of Denison's office, where there was a leather couch. "Let me rest here a moment. I do feel queer. I..."

She would have fallen if he had not sprung forward and caught her.

Together we carried her in on the couch, and, as we did so, the comb from her hair clattered to the floor.

Craig threw open the window, and bathed her face with water until there was a faint flutter of the eyelids.

"Walter," he said, as she began to revive, "I leave her to you. Keep her quiet for a few moments. She has unintentionally given me just the opportunity I want."

While she was yet hovering between consciousness and unconsciousness on the couch, he had unwrapped the package which he had brought with him. For a moment he held the comb which she had dropped near the radioscope. With a low exclamation of surprise, he shoved it into his pocket.

Then from the package he drew a heavy piece of apparatus, which looked as if it might be the motor part of an electric fan, only, in place of the fan, he fitted a long, slim, vicious-looking steel bit. A flexible wire attached the thing to the electric-light circuit, and I knew that it was an electric drill. With his coat off, he tugged at the little radium safe until he had moved it out, then dropped on his knees behind it and switched the current on in the electric drill. It was a tedious process to drill through the steel of the outer casing of the safe, and it was getting late. I shut the door so that Miss Wallace could not see.

At last, by the cessation of the low hum of the boring, I knew that he had struck the inner lead lining. Quietly I opened the door and stepped out. Craig was injecting something from a hermetically sealed lead tube into the opening he had made and allowing it to run between the two linings of lead and steel. Then, using the tube itself, he sealed the opening he had made and dabbed a little black over it.

Quickly he shoved the safe back; then around it concealed several small coils with wires, also concealed and leading out through a window to a court.

"We'll catch the fellow this time," he remarked, as he worked. "If you ever have any idea, Walter, of going into the burglary business, it would be well to ascertain if the safes have any of these little selenium cells as suggested by my friend, Mr. Hammer, the inventor. For, by them, an alarm can be given miles away the moment an intruder's bull's-eye falls on a hidden cell sensitive to light."

While I was delegated to take Miss Wallace home, Kennedy made arrangements with a small shopkeeper on the ground floor of a building that backed up on the court for the use of his back room that night, and had already set up a bell, actuated by a system of relays which the weak current from the selenium cells could operate.

It was not until nearly midnight that he was ready to leave the laboratory again, where he had been busily engaged in studying the tortoise-shell comb which Miss Wallace, in her weakness, had forgotten.

THE little shopkeeper let us in sleepily, and Kennedy

deposited a large round package on a chair in the back of the

shop, as well as a long piece of rubber tubing. Nothing had

happened so far.

As we waited, the shopkeeper, now wide awake and not at all unconvinced that we were bent on some criminal operation, hung around. Kennedy did not seem to care. He drew from his pocket a little shiny brass instrument in a lead case, which looked like an abbreviated microscope.

"Look through it," he said, handing it to me. I looked and could see thousands of minute sparks.

"What is it?" I asked.

"A spinthariscope. In that, it is possible to watch the bombardment of the countless little corpuscles thrown off by radium as they strike on the zinc-blende crystal which forms the base. When radium was originally discovered, the interest was merely in its curious properties— its power to emit invisible rays which penetrated solid substances and rendered things fluorescent, of expending energy without apparent loss.

"Then came the discovery," he went on, "of its curative powers. But the first results were not convincing. Still, now that we know the reasons why radium may be dangerous and how to protect against them, we know we possess one of the most wonderful curative agencies."

I was thinking rather of the dangers than of the beneficence of radium just now, but Kennedy continued.

"It has cured many malignant growths that seemed hopeless, brought back destroyed cells, exercised good effects in diseases of the liver and intestines, and even the baffling diseases of the arteries. The reason why harm, at first, as well as good, came, is now understood. Radium emits, as I told you before, three kinds of rays, the alpha, beta, and gamma rays, each with different properties. The emanation is another matter. It does not concern us in this case, as you will see."

I began to see that he was gradually arriving at an explanation which had baffled everyone else.

"Now, the alpha rays are the shortest," he launched forth, "in length, let us say, one inch. They exert a very destructive effect on healthy tissue. That is the cause of injury. They are stopped by glass, aluminium, and other metals, and are really particles charged with positive electricity. The beta rays come next, say, about an inch and a half. They stimulate cell-growth. Therefore they are dangerous in cancer, though good in other ways. They can be stopped by lead, and are really particles charged with negative electricity. The gamma rays are the longest, perhaps three inches long, and it is these rays which effect cures, for they check the abnormal and stimulate the normal cells. They penetrate lead. Lead seems to filter them out from the other rays. And at three inches the other rays don't reach, anyhow. The gamma rays are not charged with electricity at all, apparently."

He had brought a little magnet near the spinthariscope. I looked into it.

"A magnet," he explained, "shows the difference between the alpha, beta, and gamma rays. You see those weak and wobbly rays that seem to fall to one side? Those are the alpha rays. They have a strong action, though, on tissues and cells. Those falling in the other direction are the beta rays. The gamma rays seem to flow straight."

"Then it is the alpha rays with which we are concerned mostly, now?" I queried, looking up.

"Exactly. That is why, when radium is unprotected or insufficiently protected and comes too near, it is destructive of healthy cells, produces burns, sores, which are most difficult to heal. It is with the explanation of such sores that we must deal."

IT was growing late. We waited patiently, now, for some

time. Kennedy had evidently reserved this explanation, knowing we

should have to wait. Still, nothing happened.

Added to the mystery of the violet-colored glass plate was now that of the luminescent diamond. I was about to ask Kennedy point-blank what he thought of them, when suddenly the little bell before us began to buzz feebly under the influence of a current.

I gave a start. The faithful little selenium-cell burglar-alarm had done the trick. I knew that selenium was a good conductor of electricity in the light, poor in the dark. Some one had, therefore, flashed a light on one of the cells in the corporation office. It was the moment for which Kennedy had prepared.

Seizing the round package and the tubing, he dashed out on the street and around the corner. He tried the door opening into the Radium Corporation hallway. It was closed, but unlocked. As it yielded and we stumbled in, up the old worn wooden stairs of the building, I knew that there must be some one there.

A terrific, penetrating, almost stunning odor seemed to permeate the air, even in the hall.

Kennedy paused at the door of the office, tried it, found it unlocked, but did not open it.

"That smell is ethyl dichloracetate," he explained. "That was what I injected into the air cushions of that safe, between the two linings. I suppose my man, here, used an electric drill. He might have used thermit or an oxyacetylene blowpipe for all I would care. These fumes would discourage a cracksman from 'soup' to 'nuts'" he laughed.

As we stood an instant by the door, I realized what had happened. He had captured our man, who was asphyxiated!

Yet how were we to get to him? To go in ourselves meant to share his fate, whatever might be the effect of the drug.

Kennedy had torn the wrapping off the package. From it he drew a huge globe with bulging windows of glass in the front, and several curious arrangements on it at other points. To it he fitted the rubber tubing and a little pump. Then he placed the globe over his head, like a diver's helmet, and fastened some air-tight rubber arrangement about his neck and shoulders.

"Pump, Walter," he shouted. "This is an oxygen helmet."

Without another word he was gone into the blackness of the noxious stifle which filled the Radium Corporation office since the cracksman had struck the unexpected pocket of rapidly evaporating stuff.

I pumped furiously.

Inside, I could hear him blundering around. What was he doing?

He was coming back slowly. Was he, too, overcome? As he emerged into the darkness of the hallway where I myself was almost sickened, I saw that he was dragging with him a limp form.

A rush of outside air from the street door seemed to clear things a little. Kennedy tore off the oxygen helmet and dropped down on his knees beside the figure, working its arms in the most approved manner of resuscitation.

"I think we can do it without calling on the pulmotor," he panted. "Walter, the fumes have cleared away enough now in the outside office. Open a window—and keep that street door open, too."

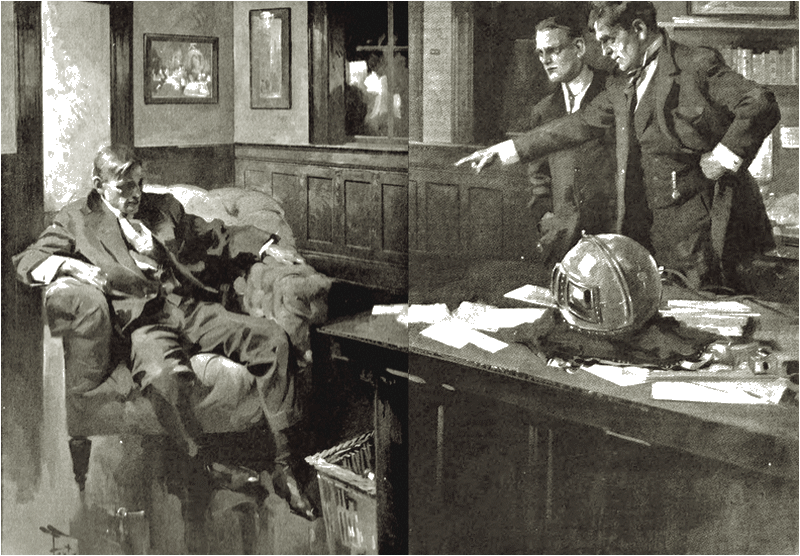

I did so, found the switch, and turned on the lights. It was Denison himself!

FOR many minutes Kennedy worked over him. I bent down,

loosened his collar and shirt, and looked eagerly at his chest

for the telltale marks of the radium which I felt sure must be

there. There was not even a discoloration.

Not a word was said, as Kennedy brought the stupefied little man around.

Denison, pale, shaken, was leaning back now in a big office-chair, gasping and holding his head. Kennedy, before him, reached down into his pocket and handed him the spinthariscope.

"You see that?" he demanded.

Denison looked through the eyepiece.

"Wh-where did you get so much of it?" he asked, a queer look on his face.

"I got that bit of radium from the base of the collar button of Hartley Haughton," replied Kennedy quietly, "a collar button which some one intimate with him had substituted for his own, bringing that deadly radium with only the minutest protection of a thin strip of metal close to the back of his neck, near the spinal cord and the medulla oblongata which controls blood pressure. That collar button was worse than the poisoned rings of the Borgias. And there is more radium in the pretty gift of a tortoise-shell comb with its paste diamonds which Miss Wallace wore in her hair. Only a fraction of an inch, not enough to cut off the deadly alpha rays, protected the wearers of those articles.

"Besides," went on Kennedy remorselessly, "when I went in there to drag you out, I saw the safe open. I looked. There was nothing in those pretty platinum tubes, as I suspected. European trust— bah! All the cheap devices of a faker with a confederate in London to send a cablegram—and another in New York to send a threatening letter!"

Kennedy extended an accusing forefinger at the man cowering before him.

Kennedy extended an accusing forefinger at the man cowering before him.

"This is nothing but a get-rich-quick scheme, Denison. There never was a milligram here in all the carefully kept reports of Miss Wallace—except what was bought outside by the corporation with the money it collected from its dupes. Haughton has been fleeced. Miss Wallace, blinded by her loyalty to you—has been fooled.

"And how did you repay it? What was cleverer, you said to yourself, than to seem to be robbed of what you never had, to blame it on a bitter rival who never existed? Then to make assurance doubly sure, you planned to disable, perhaps get rid of the come-on whom you had trimmed, and the faithful girl whose eyes you had blinded to your gigantic swindle.

"Denison," concluded Kennedy, as the man drew back, his very face convicting him, "Denison, you are the radium robber—robber, in another sense!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.