RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Cosmopolitan, February 1914, with "The Billionaire Baby"

Do you realize what may be learned from the dreams of an anxious, worried person? Their importance in diagnosis is known to the nerve specialist, and, in this remarkable story, Craig Kennedy shows how the results of their scientific interpretation may be used in crime investigation as a sure, quick means of getting at a certain type of baffling facts. It is all very wonderful and fascinating—this dabbling in the "new psychology;" and in this region of knowledge, Craig shows himself to be a master.

"I SUPPOSE you have heard of the 'billionaire baby,' Morton

Hazleton, Third?" asked Kennedy of me one afternoon.

The mere mention of the name conjured up in my mind a picture of the lusty two-year-old heir to two fortunes, as the feature articles in the Star had described that little scion of wealth—his luxurious nursery, his magnificent toys, his own motor-car, a trained nurse and a detective on guard every hour of the day and night, every possible precaution for his health and safety.

"Gad, what a lucky kid!" I exclaimed involuntarily.

"Oh, I don't know about that," put in Kennedy. "The fortune may be exaggerated. His happiness is, I'm sure."

He had pulled from his pocketbook a card and handed it to me. It read: "Gilbert Butler, American Representative, Lloyd's."

"Lloyd's?" I queried. "What has Lloyd's to do with the billion-dollar baby?"

"Very much. The child has been insured with them for some fabulous sum against accident including kidnaping."

"Yes?" I prompted, sensing a story.

"Well, there seem to have been threats of some kind, I understand. Mr. Butler has called on me once already to-day to retain my services and is going to—ah—there he is again, now."

Kennedy had answered the door-buzzer himself, and Mr. Butler, a tall, sloping-shouldered Englishman, entered.

"Has anything new developed?" asked Kennedy, introducing me.

"I can't say," replied Butler dubiously. "I rather think we have found something that may have a bearing on the case. You know Miss Haversham—Veronica Haversham?"

"The actress and professional beauty? Yes—at least, I have seen her. Why?"

"We hear that Morton Hazleton knows her, anyhow," remarked Butler dryly.

"Well?"

"Then you don't know the gossip?" he cut in. "She is said to be in a sanatorium near the city. I'll have to find that out for you. It's a fast set she has been traveling with lately, including not only Hazleton but Doctor Maudsley, the Hazletons' physician, and one or two others, who, if they were poorer, might be called desperate characters."

"Does Mrs. Hazleton know of this?"

"I can't say that, either. I presume that she is no fool."

Morton Hazleton, Junior, I knew, belonged to a rather smart group of young men. He had been mentioned in several near-scandals, but, as far as I knew, there had been nothing quite as public and definite as this one.

"Wouldn't that account for her fears?" I asked.

"Hardly," replied Butler, shaking his head. "You see, Mrs. Hazleton is a nervous wreck, but it's about the baby, and caused, she says, by her fears for its safety. It came to us only in a roundabout way—through a servant in the house who keeps us in touch. The curious feature is that we can seem to get nothing definite from her about her fears. They may be groundless."

Butler shrugged his shoulders and proceeded: "And they may be well founded. But we prefer to run no chances in a case of this kind. The child, you know, is guarded in the house. In his perambulator he is doubly guarded, and when he goes out for his airing in the automobile, two men, the chauffeur and a detective, are always there, besides his nurse, and often his mother or grandmother. Even in the nursery suite they have iron shutters which can be pulled down and padlocked at night, and are constructed so as to give plenty of fresh air, even to a scientific baby. Master Hazleton was the best sort of risk, we thought. But now—we don't know."

"You can protect yourselves, though," suggested Kennedy.

"Yes, we have, under the policy, the right to take certain measures to protect ourselves in addition to the precautions taken by the Hazletons. We have added our own detective to those already on duty. But we—we don't know what to guard against," he concluded, perplexed. "We'd like to know—that's all. It's too big a risk."

"I may see Mrs. Hazleton?" mused Kennedy.

"Yes. Under the circumstances she can scarcely refuse to see anyone we send. I've arranged already for you to meet her within an hour. Is that all right?"

"Certainly."

THE Hazleton town house was up-town, facing the river. The

large grounds adjoining made the Hazletons quite independent of

the daily infant parade along Riverside Drive.

As we entered the grounds, we could almost feel the very atmosphere on guard. We did not see the little subject of so much concern, but I remembered his much heralded advent, when his grandparents had settled a cold million on him, just as a reward for coming into the world. Evidently Morton, Senior, had hoped that Morton, Junior, would calm down, now that there was a third generation to consider. It seemed that he had not. I wondered if that had really been the occasion of the threats, or whatever it was, that had caused Mrs. Hazleton's fears, and whether Veronica Haversham or any of the fast set around her had anything to do with it.

Marguerite Hazleton was a very pretty little woman, in whom one saw instinctively the artistic temperament. She had been an actress, too, when young Morton Hazleton married her, and at first, at least, they had seemed very devoted.

We were admitted to see her in her own library, a tastefully furnished room on the second floor of the house, facing a garden at the side.

"Mrs. Hazleton," began Butler, smoothing the way for us, "of course you realize that we are working in your interests. Professor Kennedy, therefore, in a sense, represents both of us."

"I am quite sure I shall be delighted to help you," she said, with an absent expression, though not ungraciously.

Butler, having introduced us, courteously withdrew. "I leave this entirely in your hands," he said, as he excused himself. "If you want me to do anything more, call on me."

I must say that I was much surprised at the way she had received us. Was there in it, I wondered, an element of fear lest, if she refused to talk, suspicion might grow even greater? One could see anxiety plainly enough on her face, as she waited for Kennedy to begin.

A few moments of general conversation followed.

"Just what is it you fear?" he asked, after having gradually led around to the subject. "Have there been any threatening letters?"

"N-no," she hesitated, "at least nothing—definite."

"Gossip?" he hinted.

"No." She said it so positively that I fancied it might be taken for a plain "yes."

"Then, what is it?" he asked very deferentially, but firmly.

She had been looking out at the garden. "You couldn't understand," she remarked. "No detective—" she stopped.

"You may be sure, Mrs. Hazleton, that I have not come here unnecessarily to intrude," he reassured her. "It is exactly as Mr. Butler put it. We—want to help you."

I fancied there seemed to be something compelling about his manner. It was at once sympathetic and persuasive. Quite evidently he was taking pains to break down the prejudice in her mind which she had already shown toward the ordinary detective.

"You would think me crazy," she remarked slowly, "but it is just a—a dream—just dreams."

I don't think she had intended to say anything, for she stopped short and looked at him quickly, as if to make sure whether he could understand. As for myself, I must say I felt a little skeptical. To my surprise, Kennedy seemed to take the statement at its face value.

"Ah," he remarked, "an anxiety dream? You will pardon me, Mrs. Hazleton, but, before we go further, let me tell you frankly that I am much more than an ordinary detective. If you will permit me, I should rather have you think of me as a psychologist, a specialist, one who has come to set your mind at rest rather than to worm things from you by devious methods against which you have to be on guard. It is just for such an unusual case as yours that Mr. Butler has called me in. By the way, as our interview may last a few minutes, would you mind sitting down? I think you'll find it easier to talk if you can get your mind perfectly at rest, and for the moment trust to the nurse and the detectives who are guarding the garden."

She had been standing by the window during the interview and was quite evidently growing more and more nervous. With a bow, Kennedy placed her at her ease on a chaise longue.

"Now," he continued, standing near her, but out of sight, "you must try to remain free from all external influences and impressions. Don't move. Avoid every use of a muscle. Don't let anything distract you. Just concentrate your attention on your psychic activities. Don't suppress one idea as unimportant, irrelevant, or nonsensical. Simply tell me what occurs to you in connection with the dreams—everything," emphasized Craig.

I could not help feeling surprised to find that she accepted Kennedy's deferential commands, for, after all, that was what they amounted to. Almost I felt that she was turning to him for help, that he had broken down some barrier to her confidence. He seemed to exert a sort of hypnotic influence over her.

"I have had cases before which involved dreams," he was saying quietly and reassuringly. "Believe me, I do not share the world's opinion that dreams are nothing. Nor yet do I believe in them superstitiously. I can readily understand how a dream can play a mighty part in shaping the feelings of a high-tensioned woman. Might I ask exactly what it is you fear in your dreams?"

She sank her head back in the cushions.

"Oh, I have such horrible dreams," she said, at length, "full of anxiety and fear for Morton and little Morton. I can't explain it. But they are so horrible."

Kennedy said nothing. She was talking freely at last.

"Only last night," she went on, "I dreamt that Morton was dead. I could see the funeral—all the preparations and the procession. It seemed that in the crowd there was a woman I could not see her face, but she had fallen down and the crowd was around her. Then Doctor Maudsley appeared, and all of a sudden the dream changed. I thought I was on the sand at the seashore, or perhaps by a lake. I was with Junior, and it seemed as if he were wading in the water—his head bobbing up and down in the waves. It was like a desert, too—the sand. I turned, and there was a lion behind me. I did not seem to be afraid of him, although I was so close that I could almost feel his shaggy mane. Yet I feared that he might bite Junior. The next I knew I was running with the child in my arms. I escaped—and—oh, the relief!"

She sank back, half exhausted, half terrified still by the recollection.

"In your dream when Doctor Maudsley appeared," asked Kennedy, "what did he do?"

"Do?" she repeated. "In the dream? Nothing."

"Are you sure?" he asked.

"Yes. That part of the dream became indistinct. I'm sure he did nothing except to shoulder through the crowd. I think he had just entered. Then that dream ended, and the second part began."

Piece by piece, Kennedy went over it, putting it together as if it were a mosaic.

"Now, the woman. You say her face was hidden?"

She hesitated. "N-no. I saw it. But it was no one I knew."

Kennedy did not dwell on the contradiction, but added, "And the crowd?"

"Strangers, too."

"Doctor Maudsley is your family physician?" he questioned. "Yes."

"Did he call—er—yesterday?"

"He calls every day to supervise the nurse who has Junior in charge."

"Could one always be true to oneself in the face of any temptation?" he asked suddenly.

It was a bold question. Yet such had been the gradual manner of his leading-up to it that, before she knew it, she had answered quite frankly, "Yes—if one always thought of home and her child, I cannot see how one could help controlling herself."

She seemed to catch her breath, almost as though the words had escaped her before she knew it.

"Is there anything besides your dream that alarms you," Kennedy asked, changing the subject quickly, "any suspicion of—say the servants?"

"No," she said, watching him now. "But some time ago we caught a burglar up-stairs here. He managed to escape. That has made me nervous."

"Anything else?"

"No," she said positively, this time on her guard. Kennedy saw that she had made up her mind to say no more.

"Mrs. Hazleton," he said, rising, "I can hardly thank you too much for the manner in which you have met my questions. It will make it much easier for me to quiet your fears. And if anything else occurs to you, you may rest assured I shall violate no confidences in your telling me."

I could not help the feeling, however, that there was just a little air of relief on her face as we left.

"H-m," mused Kennedy, as we walked along after leaving the house. "There were several complexes, as they are called, there—the most interesting and important being the erotic, as usual. Now, take the lion in the dream, with his mane. That, I suspect, was Doctor Maudsley. If you are acquainted with him, you will recall his heavy, almost tawny beard."

Kennedy seemed to be revolving something in his mind, and I did not interrupt.

"In spite of the work of thousands of years, little progress has been made in the scientific understanding of dreams," he remarked, a few moments later. "Freud, of Vienna—you recall the name?—has done most, I think, in that direction."

I recalled something of the theories of the Freudists, but said nothing.

"It is an unpleasant feature of Freud's philosophy," he went on, "but he finds the conclusion irresistible that all humanity, underneath the shell, is sensuous and sensual in nature. Practically all dreams betray some delight of the senses. There is, according to the theory, always a wish hidden or expressed in a dream. The dream is one of three things—the open, the disguised, or the distorted fulfilment of a wish, sometimes recognized, sometimes repressed.

"Often dreams, apparently harmless, turn out to be sinister, if we take pains to interpret them. All have the mark of the beast. For example, there was that unknown woman who had fallen down and was surrounded by a crowd. If a woman dreams that, it can mean only a fallen woman. That is the symbolism. The crowd always denotes a secret.

"Take, also, the dream of death. If there is no sorrow felt, then there is another cause for it. But if there is sorrow, then the dreamer really desires death or absence. I expect to have you quarrel with that. But read Freud, and remember that, in childhood, death is synonymous with being away. Thus, for example, if a girl dreams that her mother is dead, perhaps it means only that she wishes her away so she can enjoy some pleasure that, her strict parent, by her presence, denies.

"Then there was that dream about the baby in the water. That, I think, was a dream of birth. You see, I asked her practically to repeat the dreams, because there were several gaps. At such points, one usually finds, first, hesitation, then something that shows one of the main complexes.

"Now, from the tangle of the dream-thought, I find that she fears that her husband is friendly with another woman, and that, perhaps unconsciously, she has turned to Doctor Maudsley for sympathy. Doctor Maudsley, as I said, is not only bearded, but somewhat of a social lion. He had called on her the day before. Of such stuff are all dream-lions when there is no fear. But she shows that she has been guilty of no wrong doing—she escaped and felt relieved."

"I'm glad of that," I put in. "I don't like these scandals. On the Star, when I have to report them, I do it always under protest. I don't know what your psychoanalysis is going to show in the end, but I, for one, have the greatest sympathy for that poor little woman in the big house alone, surrounded by and dependent on servants, while her husband is out collecting scandals."

"Which suggests our next step," he said, turning the subject. "I hope that Butler has found out the retreat of Veronica Haversham."

WE discovered Miss Haversham, at last, at Doctor Klemm's

sanatorium, up in the hills of Westchester County, a delightful

place with a reputation for its rest-cures. Doctor Klemm was an

old friend of Kennedy's, having had some connection with the

medical school at the university.

She had gone up there rather suddenly, it seemed, to recuperate. At least, that was what was given out, though there seemed to be much mystery about her, and she was taking no treatment, so far as was known.

"Who is her physician?" asked Kennedy, of Doctor Klemm, as we sat in his luxurious office.

"A Doctor Maudsley, in the city." Kennedy glanced quickly at me in time to check an exclamation.

"I wonder if I could see her?"

"Why, of course—if she is willing," replied Doctor Klemm.

"I will have to have some excuse," ruminated Kennedy. "Tell her I am a specialist in nervous troubles from the city—have been visiting one of the other patients—anything."

Doctor Klemm pulled down a switch on a large, oblong oak box on his desk, asked for Miss Haversham, and waited a moment.

"What is that?" I asked.

"A vocaphone," replied Kennedy. "This sanatorium is quite up to date, Klemm."

The doctor nodded and smiled. "Yes, Kennedy," he replied. "Communicating with every suite of rooms we have the vocaphone. I find it very convenient to have these microphones, as I suppose you would call them, catching your words without talking into them directly as you have to do into the telephone, and then, at the other end, emitting the words without the use of an ear-piece, from the box itself, as if from a megaphone horn—Miss Haversham, this is Doctor Klemm. There is a Doctor Kennedy here, a specialist from New York, visiting another patient. He'd like very much to see you, if you can spare a few minutes."

"Tell him to come up." The voice seemed to come from the vocaphone as though it were in the room with us.

Veronica Haversham was indeed wonderful, one of the leading figures in the night life of New York, a statuesque brunette of striking beauty, though, I had heard, of often ungovernable temper. Yet there was something strange about her face, here. It seemed perhaps a little yellow, and I am sure that her nose had a peculiar look as if she were suffering from an incipient rhinitis. The pupils of her eyes were as fine as pin-heads; her eyebrows were slightly elevated. Indeed, I felt that she had made no mistake in taking a rest if she would preserve the beauty which had made her popularity so meteoric.

"Miss Haversham," began Kennedy, "they tell me that you are suffering from nervousness. Perhaps I can help you. At any rate, it will do no harm to try. I know Doctor Maudsley well, and if he doesn't approve—well, you may throw the treatment into the waste-basket."

"I'm sure I have no reason to refuse," she said. "What would you suggest?"

"Well, first of all, there is a very simple test I'd like to try. You won't find that it bothers you in the least. And if I can't help you—then no harm is done."

Again I watched Kennedy, as he tactfully went through the preparations for another kind of psychoanalysis, placing Miss Haversham at her ease on a davenport, in such a way that nothing would distract her attention. As she reclined against the leather pillows in the shadow, it was not difficult to understand the lure by which she held together the little coterie of her intimates. One beautiful white arm, bare to the elbow, hung carelessly over the edge of the davenport, displaying a plain gold bracelet.

"Now," began Kennedy, on whom I knew the charms of Miss Haversham produced a negative effect, although one would never have guessed it from his manner, "as I read off from this list of words, I wish that you would repeat the first thing—anything," he emphasized, "that comes into your head, no matter how trivial it may seem. Don't force yourself to think. Let your ideas flow naturally. It depends altogether on your paying attention to the words and answering as quickly as you can. Remember: the first word that comes into your mind. It is easy to do. We'll call it a game," he reassured.

Kennedy handed a copy of the list to me to record the answers. There must have been some fifty words, apparently senseless, chosen at random, it seemed. They were:

"The Jung association word-test is part of the Freud psychoanalysis, also," he whispered to me. "You remember we tried something based on the same idea once before?"

I nodded. I had heard of the thing in connection with blood-pressure tests, but not this way.

Kennedy called out the first word, "head," while in his hand he held a stopwatch which registered to one-fifth of a second.

Quickly she replied, "ache," with an involuntary movement of her hand toward her beautiful forehead.

"Good!" exclaimed Kennedy. "You seem to grasp the idea better than most of my patients."

I had recorded the answer, he the time, and we found out, I recall afterward, that the time averaged something like two and two-fifth seconds.

I thought her reply to the second word, "green," was curious. It came quickly—"envy."

I shall not attempt to give all the replies, but merely some of the most significant. There did not seem to be any hesitation about most of the words, but whenever Kennedy tried to question her about a word that seemed to him interesting, she made either evasive or hesitating answers, until it became evident that, in the back of her head, there was some idea which she was repressing and concealing from us—something that she set off with a mental "No Thoroughfare."

Kennedy had finished going through the list, and was now studying over the answers and comparing the time-records.

"Now," he said, at length, running his eyes over the words again, "I want to repeat the performance. Try to remember and duplicate your first replies," he said.

Again he went through what at first had seemed to me to be a solemn farce, but which I began to see was quite important. Sometimes she would repeat the answer exactly as before. At other times a new word would occur to her. Kennedy was keen to note all the differences in the two lists.

One which I recall, because the incident made an impression on me, had to do with the trio, "death—life—inevitable."

"Why that?" he asked casually.

"Haven't you ever heard the saying: 'One should let nothing which one can have escape, even if a little wrong is done; no opportunity should be missed. Life is so short; death inevitable'?"

There were several others which to Kennedy seemed more important, but long after we had finished I pondered this answer. Was that her philosophy of life? Undoubtedly she would never have remembered the phrase if it had not been so, at least in a measure.

She had begun to show signs of weariness, and Kennedy quickly brought the conversation around to subjects of apparently a general nature, but skilfully contrived so as to lead the way along lines her answers had indicated.

Kennedy had risen to go, still chatting. Almost unintentionally he picked up from a dressing-table a bottle of white tablets, without a label, shaking it to emphasize an entirely, and I believe purposely, irrelevant remark.

"By the way," he said, breaking off naturally, "what is that?"

"Only something Doctor Maudsley has prescribed for me," she answered quickly.

As he replaced the bottle and went on with the thread of the conversation, I saw that, in shaking the bottle, he had abstracted a couple of the tablets before she realized it.

"I can't tell you just what to do without thinking the case over," he concluded. "Yours is a peculiar case, Miss Haversham, baffling. I'll have to study it over, perhaps ask Doctor Maudsley if I may see you again. Meanwhile, I am sure what he is doing is the correct thing."

Inasmuch as she had said nothing about what Doctor Maudsley was doing, I wondered whether there was not just a trace of suspicion in her glance at him from under her long, dark lashes.

"I can't see that you have done anything," she remarked pointedly. "But then doctors are queer—queer."

That parting shot also had in it, for me, something to ponder over. In fact, I began to wonder if she might not be a great deal more clever than even Kennedy gave her credit for being, whether she might not have submitted to his tests for pure love of pulling the wool over his eyes.

Down-stairs again, Kennedy paused only long enough to speak a few words with Doctor Klemm.

"I suppose you have no idea what Doctor Maudsley has prescribed for her?" he asked carelessly.

"Nothing, as far as I know, except rest and simple food."

He seemed to hesitate, then he said under his voice, "I suppose you know that she is a regular dope fiend, seasons her cigarettes with opium, and all that."

"I guessed as much," remarked Kennedy, "but how does she get it here?"

"She doesn't."

"I see," remarked Craig, apparently weighing now the man before him. At length he seemed to decide to risk something.

"Klemm," he said, "I wish you would do something for me. I see you have the vocaphone here. Now if—say Hazleton—should call—will you listen in on that vocaphone for me?"

Doctor Klemm looked squarely at him.

"Kennedy," he said, "it's unprofessional, but..."

"So it is to let her be doped up under guise of a cure."

"What?" he asked, startled. "She's getting the stuff now?"

"No, I didn't say she was getting opium, or from anyone here. All the same, if you would just keep an ear open..."

"It's unprofessional, but—you'd not ask it without a good reason. I'll try."

It was very late when we got back to the city, and we dined at an up-town restaurant, which we had almost to ourselves.

KENNEDY had placed the little whitish tablets in a small paper

packet for safekeeping. As we waited for our order, he drew one

from his pocket, and after looking at it a moment, crushed it in

a powder in the paper.

"What is it?" I asked curiously. "Cocaine?"

"No." He had tried to dissolve a little of the powder in some water from the glass before him, but it would not dissolve.

As he continued to look at it, his eye fell on the cut-glass vinegar-cruet before us. It was full of white vinegar.

"Really acetic acid," he remarked, pouring out a little.

The white powder dissolved. For several minutes he continued looking at the stuff.

"That, I think," he remarked finally, "is heroin."

"Oh, I've heard of heroin," I replied, with added interest now. "It's a new drug that has produced a new habit, isn't it? What is the stuff?"

"Yes," he replied, "the habit is comparatively new, although in Paris, I believe, they call the drug fiends, 'heroinomaniacs.' It is a derivative of morphine. Its scientific name is diacetyl-morphine. It is New York's newest peril, one of the most dangerous drugs yet. Thousands are slaves to it, although its sale is supposedly restricted. It is rotting the heart out of the Tenderloin. Did you notice Veronica Haversham's yellowish whiteness, her down-drawn mouth, elevated eyebrows, and contracted eyes? She may have taken it up to escape other drugs. Some people have—and have just got a new habit. It can be taken hypodermically, or in a tablet, or by powdering the tablet to a white crystalline powder and snuffing up the nose. That's the way she takes it. It produces rhinitis of the nasal passages, which I see you observed but did not understand. It has a more profound effect than morphine, and is ten times as powerful as codeine. And one of the worst features is that so many people start with it thinking it is as harmless as it has been advertised. I wouldn't be surprised if she used from seventy-five to a hundred one-twelfth-grain tablets a day. Some of them do."

"And Doctor Maudsley," I asked quickly, "do you think it is through him or in spite of him?"

"That's what I'd like to know. About those words," he continued, "what did you make of the list and the answers?"

I had made nothing and said so, rather quickly.

"Those," he explained, "were words selected and arranged to strike almost all the common complexes in analyzing and diagnosing. You'd think any intelligent person could give a fluent answer to them,—perhaps a misleading answer. But try it yourself, Walter. You'll find you can't. You may start all right, but not all the words will be reacted to in the same time or with the same smoothness and ease. Yet, like the expressions of a dream, they often seem senseless. But they have a meaning as soon as they are psychoanalyzed. All the mistakes in answering the second time, for example, have a reason, if we can only get at it. They are not arbitrary answers, but betray the inmost subconscious thoughts—those things marked, split off from consciousness, and repressed into the unconscious. Associations, like dreams, never lie. You may try to conceal the emotions and unconscious actions, but you can't."

I listened, fascinated by Kennedy's explanation.

"Anyone can see that that woman has something on her mind besides the heroin habit. It may be that she is trying to shake the habit off in order to do it; it may be that she seeks relief from her thoughts by refuge in the habit, and it may be that some one has purposely caused her to contract this new habit in the guise of throwing off an old one. The only way to tell is to study the case."

He paused. He had me keenly on edge, but I knew that he was not yet in a position to answer his queries positively.

"Now I found," he went on, "that the religious complexes were extremely few; as I expected, the erotic were many. If you will look over the three lists you will find something queer about every such word as 'child,' 'to marry,' 'bride,' 'to lie,' 'stork,' and so on. We're on the right track. That woman does know something about that child."

"My eye catches the words, 'to sin,' 'to fall,' 'pure,' amid others," I remarked, glancing over the list.

"Yes; there's something there, too. I got the hint for the drug from her hesitation over 'needle' and 'white.' But the main complex has to do with words relating to that child and to love. In short, I think we are going to find it to be the reverse of the rule of the French—that it will be a case of cherchez les hommes."

Early the next day Kennedy, after a night of studying over the case, journeyed up to the sanatorium again. We found Doctor Klemm eager to meet us.

"What is it?" asked Kennedy, equally eager.

"I overheard some surprising things over the vocaphone," he hastened. "Hazleton called. Why, there must have been some wild orgies in that precious set of theirs, and—would you believe it? many of them seem to have been at what Doctor Maudsley calls his' stable studio,' a den he has fixed up artistically over his garage on a side street."

"Indeed?"

"I couldn't get it all, but I did hear her repeating once, over and over, to Hazleton, 'Aren't you all mine? Aren't you all mine?' There must be some vague jealousy lurking in the heart of that ardent woman. I can't figure it out."

"I'd like to see her again," re-marked Kennedy. "Will you ask her if I may?"

A FEW moments later we were in the sitting-room of her suite.

She received us rather ungraciously, I thought.

"Do you feel any better?" asked Kennedy.

"No," she replied curtly. "Excuse me for a moment. I wish to see that maid of mine. Clarisse!"

She had scarcely left the room when Kennedy was on his feet. The bottle of white tablets, nearly empty, was still on the table. I saw him take some very fine white powder and dust it quickly over the bottle. It seemed to adhere, and from his pocket he hastily drew a piece of what seemed to be specially prepared paper, laid it over the bottle where the powder adhered, fitting it over the curves. He withdrew it quickly, for outside we heard her light step returning. I am sure she either saw or suspected that Kennedy had been touching the bottle of tablets, for there was a look of startled fear on her face.

"Then you do not feel like continuing the tests we abandoned last evening?" asked Kennedy, apparently not noticing her look.

"No, I do not," she almost snapped. "You—you are detectives. Mrs. Hazleton has sent you."

"Indeed, Mrs. Hazleton has not sent us," insisted Kennedy, never for an instant showing his surprise at her mention of the name.

"You are. You can tell her, you can tell everybody. I'll tell—I'll tell, myself. I won't wait. That child is mine—mine—not hers. Now—go!"

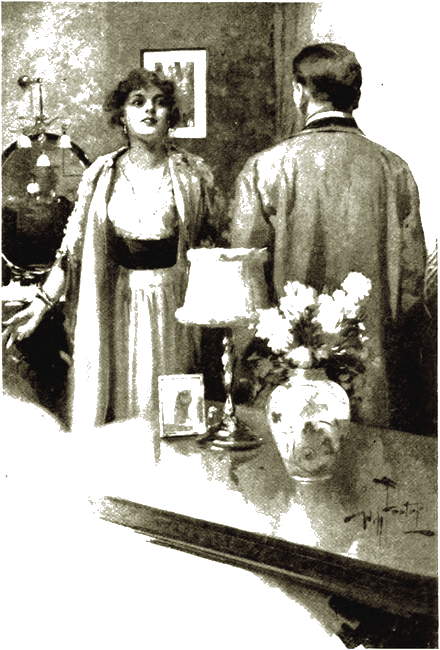

Veronica Haversham, on the stage, never towered in a fit of passion as she did now in real life, as her ungovernable feelings broke forth on us.

Veronica Haversham, on the stage, never towered

in a fit of passion as she did now in real life.

I was astounded, bewildered, at the revelation, the possibilities in those simple words, "The child is mine." For a moment I was stunned. Then, as the full meaning dawned on me, I wondered, in a flood of consciousness, whether it was true. Was it the product of her drug-disordered brain? Had her desperate love for Hazleton produced an hallucination?

Kennedy, silent, saw that the case demanded quick action. I shall never forget the breathless ride down from the sanatorium to the Hazleton house on Riverside Drive.

"Mrs. Hazleton," he cried, as we hurried in, "you will pardon me for this unceremonious intrusion, but it is most important. May I trouble you to place your fingers on this paper—so?"

He held out to her a piece of the prepared paper. She looked at him once, then saw from his face that he was not to be questioned. Almost tremulously she did as he said, saying not a word.

"Thank you," he said quickly. "Now, if I may see little Morton..."

It was the first time we had seen the baby about whom the rapidly thickening events were crowding. He was a perfect specimen of the well-cared-for, scientific infant.

Kennedy took the little chubby fingers playfully in his own. He seemed at once to win the child's confidence, though he may have violated scientific rules. One by one he pressed the little fingers on the paper until little Morton crowed with delight as one little piggy after another "went to market." He had deserted thousands of dollars' worth of toys just to play with the simple piece of paper Kennedy had brought with him. As I looked at him, I thought of what Kennedy had said at the start. Perhaps this innocent child was not to be envied, after all. I could hardly restrain my excitement over the astounding situation which had suddenly developed.

"That will do," announced Kennedy finally, carelessly folding up the paper and slipping it into his pocket. "You must excuse me now."

"You see," he explained, on the way to the laboratory, "that powder adheres to fresh finger-prints, taking all the gradations. Then the paper with its paraffin-and-glycerin coating takes off the powder."

In the laboratory he buried himself in work, with microscope, compasses and calipers."

"Walter," he called suddenly, "get Doctor Maudsley on the telephone. Tell him to come immediately to the laboratory."

Meanwhile, Kennedy was busy arranging what he had discovered in logical order and putting on it the finishing touches.

As Doctor Maudsley entered, Kennedy greeted him, and began by plunging directly into the case, in answer to his rather discourteous inquiry as to why he had been so hastily summoned.

"Doctor Maudsley," said Craig, "I have asked you to call alone because, while I am on the verge of discovering the truth in an important case affecting Morton Hazleton and his wife, I am frankly perplexed as to how to go ahead."

The doctor seemed to shake with excitement as Kennedy proceeded.

"Doctor Maudsley," Craig added, dropping his voice, "Is Morton, Third, the son of Marguerite Hazleton or not? You were the physician in attendance on her at the birth. Is he?"

Maudsley had been watching Kennedy furtively at first, but, as he rapped out the words, I thought the doctor's eyes would pop out of his head. Perspiration in great beads collected on his face.

"P-Professor K-Kennedy," he muttered, frantically rubbing his face and lower jaw as if to compose the agitation he could so ill conceal, "let me explain."

"Yes, yes—go on," urged Kennedy.

"Mrs. Hazleton's baby was born—dead. I knew how much she and the rest of the family had longed for an heir, how much it meant. And I—substituted for the dead child a new-born baby from the maternity hospital. It—it belonged to Veronica Haversham—then a poor chorus girl. I did not intend that she should ever know it. I intended that she should think her baby was dead. But in some way she found out. Since then she has become a famous beauty, has numbered among her friends even Hazleton himself. For nearly two years I have tried to keep her from divulging the secret. From time to time, hints of it have leaked out. I knew that if Hazleton, with his infatuation for her, were to learn—"

"And Mrs. Hazleton, has she been told?" interrupted Kennedy.

"I have been trying to keep it from her as long as I can, but it has been difficult to keep Veronica from telling it. Hazleton himself is so wild over her. And she wanted her son, as she——"

"Maudsley," snapped out Kennedy, slapping down on the table the mass of prints and charts which he had hurriedly collected and was studying, "you lie! Morton is Marguerite Hazleton's son. The whole story is blackmail. I knew it when she told me of her dreams, and I suspected first some such devilish scheme as yours. Now I know it scientifically."

"Maudsley," snapped out Kennedy, slapping down on

the table the mass of prints and charts, "you lie!"

He turned over the prints.

"I suppose that study of these prints, Maudsley, will convey nothing to you. I know that it is usually stated that there are no two sets of finger-prints in the world that are identical or that can be confused. Still, there are certain similarities of fingerprints and other characteristics, and these similarities have recently been exhaustively studied by Bertillon, who has found that there are clear relationships, sometimes, between mother and child in these respects. If Solomon were alive, Doctor, he would not now have to resort to the expedient to which he did when the two women disputed over the right to the living child. Modern science is now deciding by exact laboratory methods the same problem as he solved by his unique knowledge of feminine psychology.

"I saw how this case was tending and not a moment too soon. I said to myself, 'The hand of the child will tell.' By the very variations in unlike things, such as finger- and palm-prints, as tabulated and arranged by Bertillon after study in thousands of cases, by the very loops, whorls, arches, and composites, I have proved my case.

"The dominance, not the identity, of heredity through the infinite varieties of finger markings is sometimes very striking. Unique patterns in a parent have been repeated with marvelous accuracy in the child. I knew that negative results might prove nothing in regard to parentage—a caution which it is important to observe. But I was prepared to meet even that.

"I would have gone on into other studies, such as Tammasia's, of heredity in the veining of the back of the hands; I would have measured the hands, compared the relative proportion of the parts; I would have studied them under the X-ray as they are being studied to-day; I would have tried the Reichert blood-crystal test, which is being perfected now so that it will tell heredity itself. There is no scientific stone I would have left unturned until I had delved at the truth of this riddle. Fortunately, it was not necessary. Simple finger-prints have told me enough. And, best of all, it has been in time to frustrate that devilish scheme you and Veronica Haversham have been slowly unfolding."

Maudsley crumpled up, as it were, at Kennedy's denunciation.

"Yes," cried Kennedy, with extended forefinger, "you may go—for the present. Don't try to run away. You're watched from this moment on."

Maudsley had retreated precipitately.

I looked at Kennedy inquiringly. What to do? It was indeed a delicate situation, requiring the utmost care to handle. If the story had been told to Hazleton, what might he not have already done? He must be found, first of all, if we were to meet the conspiracy of these two.

Kennedy reached quickly for the telephone. "There is one stream of scandal that can be dammed at its source," he remarked, calling a number. "Hello, Klemm's Sanatorium? I'd like to speak with Miss Haversham. What—gone? Disappeared? Escaped?"

He hung up the receiver blankly.

A thousand ideas flew through our minds at once. Had she perceived the import of our last visit, and was she now on her way to complete her plotted slander of Marguerite Hazleton, though it pulled down on herself in the end the whole structure?

Hastily, Kennedy called Hazleton's home, Butler, and one after another of Hazleton's favorite clubs. It was not until noon that Butler himself found Hazleton and came with him, under protest, to the laboratory.

"What is it—what have you found?" cried Butler, his lean form aquiver with suppressed excitement.

Briefly, one fact after another, sparing Hazleton nothing, Kennedy poured forth the story, how by hint and innuendo Maudsley had been working on Marguerite, undermining her, little knowing that he had attacked in her a very tower of strength, how Veronica, infatuated by Hazleton, had infatuated him, had led him on step by step.

Pale and agitated, with nerves unstrung by the life he had been leading, Hazleton listened.

"The scoundrels," he ground out, as Kennedy finished by painting the picture of the brave little broken-hearted woman fighting off she knew not what, and the golden-haired, innocent baby stretching out his arms in glee at the very chance to prove that he was what he was. "The scoundrels—take me to Maudsley—now! I must see Maudsley. Quick!"

AS we pulled up before the door of the reconstructed

stable-studio, Kennedy jumped out. The door was unlocked. Up the

broad flight of stairs, Hazleton went, two at a time. We followed

closely.

On the divan in the room that had been the scene of so many orgies, were two figures—Veronica Haversham and Doctor Maudsley.

On the divan in the room were two figures—Veronica Haversham and Doctor Maudsley.

She must have gone there directly after our visit to Doctor Klemm's, must have been waiting for him when he returned with his story of the exposure to add to her fears of us as Mrs. Hazleton's detectives.

Hazleton looked, aghast.

He leaned over and took hold of them, one after the other.

The two were cold and rigid.

"An overdose of heroin, this time," muttered Kennedy.

My head was in a whirl.

Hazleton stared blankly at the two figures before him, as the truth burned itself indelibly into his soul. He covered his face with his hands. And still he saw it all.

Craig said nothing. He was content to let what he had shown work in the man's mind.

"For the sake of—that baby—would she—would she forgive?" asked Hazleton, turning desperately toward Kennedy.

Deliberately, Kennedy faced him, not as scientist to millionaire, but as man to man.

"From my psychoanalysis," he said slowly, "I should say that it is within your power, in time, to change those dreams."

Hazleton grasped Kennedy's hand before he knew it.

"Kennedy—home—quick! This is the first manful impulse I have had for two years. And, Jameson—you'll tone down that part of it in the newspapers that Junior—might read—when he grows up?"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.