RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Cosmopolitan, January 1914, with "The Air-Pirate"

You don't have to read dry scientific journals to keep in touch with the marvelous twentieth-century progress of inventions and discovery—you find it recorded in these Craig Kennedy stories. Jules Verne never dreamed of some of the feats that Kennedy performs with his modern apparatus and methods. And yet everything he does is possible and practical—based on the very latest scientific developments throughout the world. In this story, his detective skill is called upon to solve a mystery that is terrorizing a fashionable summer colony.

"CAN you arrange to spend the week-end with me at the Stuyvesant Verplancks at Bluffwood?" asked Kennedy, over the telephone one afternoon, as I was just completing my work on the Star.

"How long since society took you up?" I asked airily, adding, "Is it a large house-party you're getting up?"

"You have heard of the so-called 'phantom bandit' of Bluffwood, haven't you?" he returned rather brusquely, as though there were no time now for bantering.

I confess that I had forgotten it, but now I recalled that, for several days, I had been reading little paragraphs about robberies of the big estates on the Long Island shore of the Sound. One of the newspaper correspondents had called the robber a "phantom bandit," but I had thought it nothing more than an attempt to make good copy out of a rather ordinary occurrence.

"Well," he hurried on, "that's the reason why I have been 'taken up by society,' as you so elegantly phrase it. From the secret hiding-places of the boudoirs and safes of fashionable women at Bluffwood, thousands of dollars' worth of jewels and other trinkets have mysteriously vanished. Of course you'll come along. Why, it will be just the story to tone up that alleged page of society news you hand out in the Sunday Star. There—we're quits, now. Seriously, though, Walter, it really seems to be a very baffling case, or rather series of cases. The whole colony out there is terrorized. They don't know who the robber is, or how he operates, or who will be the next victim, but his skill and success seem almost uncanny. Mr. Verplanck has put one of his cars at my disposal, and I'm up here at the laboratory gathering some apparatus that may be useful. I'll pick you up anywhere between this and the Bridge—how about Columbus Circle in half an hour?"

"Good," I agreed, deciding quickly from his tone and manner of assurance that it would be a case I could not afford to miss.

THE Stuyvesant Verplancks, I knew, were among the leaders of

the rather recherchée society at Bluffwood, and the pace

at which Bluffwood moved and had its being was such as to

guarantee a good story in one way or another.

"Why," remarked Kennedy, as we sped out over the picturesque roads of the north shore of Long Island, "this fellow, or fellows, seems to have taken the measure of all the wealthy members of the exclusive organizations out there—the Westport Yacht Club, the Bluffwood Country Club, the North Shore Hunt, and all of them. It's a positive scandal—the ease with which he seems to come and go without detection, striking now here, now there, often at places that it seems physically impossible to get at, and yet always with the same diabolical skill and success. One night he will take some baubles worth thousands; the next, pass them by for something apparently of no value at all, a piece of bric-à-brac, a bundle of letters, anything."

"Seems purposeless, insane, doesn't it?" I put in.

"Not when he always takes something—often more valuable than money," returned Craig. He leaned back in the car and surveyed the glimpses of bay and countryside as we were whisked by the breaks in the trees.

"Walter," he remarked meditatively, "have you ever considered the possibilities of blackmail if the right sort of evidence were obtained under this new 'white-slave' act? Scandals that some of the fast set may be inclined to wink at, that, at worst, used to end in Reno, become felonies, with federal-prison sentences looming up in the background. Think it over."

Stuyvesant Verplanck had telephoned rather hurriedly to Craig earlier in the day, retaining his services, but telling in the briefest way only of the extent of the depredations, and hinting that more than jewelry might be at stake.

It was a pleasant ride, but we finished it in silence. Verplanck was, as I recalled, a large, masterful man, one of those who demanded and liked large things—such as the estate of several hundred acres which we at last entered.

It was on a neck of land with the restless waters of the Sound on one side and the calmer waters of the bay on the other. Westport Bay lay in a beautifully wooded, hilly country, and the house itself was on an elevation, with a huge sweep of terraced lawn before it down to the water's edge.

AS we pulled up under the broad stone porte-cochère,

Verplanck, who had been expecting us, led the way into his

library, a great room, literally crowded with curios and objects

of art which he had collected on his travels.

"You will recall," began Verplanck, wasting no time over preliminaries, but plunging directly into the subject, "that the prominent robberies of late have been at sea-coast resorts, especially on the shores of Long Island Sound within, say, a hundred miles of New York. There has been a great deal of talk about dark and muffled automobiles that have conveyed mysterious parties swiftly and silently across country.

"My theory," he went on self-assertively, "is that the attack has been made always along water routes. Under shadow of darkness, it is easy to slip into one of the sheltered coves or miniature fiords with which the north coast of the island abounds, and land a cutthroat crew primed with exact information of the treasure on some of these estates. Once the booty is secured, the criminal could put out again into the Sound without leaving a clue."

He seemed to be considering his theory. "Perhaps the robberies last summer at Narragansett, Newport, and a dozen other New England places were perpetrated by the same cracksmen. I believe," he concluded, lowering his voice, "that there plies to-day on the wide waters of the Sound a slim, swift motor-boat which wears the air of a pleasure craft, yet is as black a pirate as ever flew the Jolly Roger. She may at this moment be anchored off some exclusive yacht club, flying the respectable burgee of the club—who knows?"

He paused as if his deductions settled the case so far. He would have resumed in the same vein if the door had not opened. A lady in a cobwebby gown entered the room. She was of middle age, but had retained her youth with a skill that her sisters of less leisure always envy. Evidently she had not expected to find anyone, yet nothing seemed to disconcert her.

"Mrs. Verplanck," her husband introduced. "Professor Kennedy and his associate, Mr. Jameson—the detectives we have heard about. We were discussing the robberies."

"Oh, yes," she said, smiling, "my husband has been thinking of forming himself into a vigilance committee. The local authorities are all at sea."

"You have not been robbed yourself?" queried Craig tentatively.

"Indeed we have," exclaimed Verplanck quickly. "The other night I was awakened by the noise of some one down here in this very library. I fired a shot, wild, and shouted, but before I could get down here, the intruder had fled through a window. Mrs. Verplanck was awakened by the rumpus, and both of us heard a peculiar whirring noise.

"Like an automobile muffled down," she put in.

"No," he asserted vigorously, "more like a powerful motor-boat, one with the exhaust under water."

"Did the intruder get anything?" asked Kennedy.

"That's the lucky part. He had just opened this safe, apparently, and begun to ransack it. This is my private safe. Mrs. Verplanck has another built into her own room up-stairs where she keeps her jewels."

"It is not a very modern safe, is it?" ventured Kennedy. "The fellow ripped off the outer casing with what they call a 'can-opener.'"

"No. I keep it against fire rather than burglars. But he overlooked a box of valuable heirlooms, some silver with the Verplanck arms. I think I must have scared him off just in time. He seized a package in the safe, but it was only some business correspondence. I don't relish having it lost, particularly. It related to a gentleman's agreement a number of us had in the recent cotton-corner. I suppose the government would like to have it. But—here's the point: If it is so easy to get in and get away, no one in Bluffwood is safe."

"Why, they robbed the Montgomery Carter place the other night," remarked Mrs. Verplanck, "and almost got a lot of old Mrs. Carter's jewels as well as stuff belonging to her son, Montgomery, Junior. That was the first robbery. Mr. Carter, that is, Junior—'Monty,' everyone calls him—and his chauffeur almost captured the fellow, but he managed to escape into the woods."

"Oh, no one is safe any more," reiterated Verplanck. "Carter seems to be the only one who has had a real chance at him, and he was able to get away neatly."

"But he's not the only one who got off without a loss," Mrs. Verplanck put in. "The last visit—" Then she paused.

"Where was the last attempt?" asked Kennedy.

"At the house of Mrs. Hollingsworth—around the point on this side of the bay. You can't see it from here."

"I'd like to go there," remarked Kennedy.

"Very well. Car or boat?"

"Boat, I think."

"Suppose we go in my little runabout, the Streamline II? She's as fast as any ordinary automobile."

"Very good. Then we can get an idea of the harbor."

"I'll telephone first that we are coming," said Verplanck.

"I think I'll go, too," considered Mrs. Verplanck, ringing for a heavy wrap.

"Just as you please," said Verplanck.

THE Streamline was a three-stepped boat which

Verplanck had built for racing, a beautiful craft, managed much

like a racing automobile. As she started from the dock, the

purring drone of her eight cylinders sent her feathering over the

waves like a skipping-stone. She sank back into the water, her

bow leaping upward, a cloud of spray in her wake, like a

waterspout.

The Hollingsworth house was a beautiful little place down the bay from the yacht club but not as far as Verplancks or the Carter estate, which was opposite.

Mrs. Hollingsworth was a wealthy divorcee, living rather quietly with her two children, of whom the courts had awarded her the care. She was a striking woman. I gathered, however, that she was not on very good terms with the little Westport clique in which the Verplancks moved, or, at least, not with Mrs. Verplanck. The two women seemed to regard each other rather coldly, I thought, although Mr. Verplanck, manlike, seemed to scorn any distinctions and was more than cordial. I wondered why Mrs. Verplanck had come.

"Yes," replied Mrs. Hollingsworth, when the reason for our visit had been explained, "the attempt was a failure. I happened to be awake, rather late, or perhaps you would call it early. I thought I heard a noise as if some one was trying to break into the drawing-room through the window. I switched on all the lights. I have them arranged so, for just that purpose of scaring off intruders. Then, as I looked out of my window on the second floor, I fancied I could see a dark figure slink into the shadow of the shrubbery at the side of the house. Then there was a whir. It might have been an automobile, although it sounded differently from that-more like a motor-boat. At any rate, there was no trace of a car that we could discover in the morning. The road had been oiled, too, and a car would have left marks. And yet some one was here. There were marks on the drawing-room window, just where I heard the sounds."

Who could it be? I asked myself, as we left. I knew that the great army of chauffeurs was infested with thieves, thugs, and gunmen. Then, too, there were maids, always useful as scouts for these corsairs who prey on the rich. Yet so adroitly had everything been done in these cases, that not a clue seemed to have been left behind.

WE returned to Verplanck's in the Streamline in

record time, dined, and then found McNeill, a local detective,

waiting to supply his quota of information. McNeill was of the

square-toed, double-chinned, bull-necked variety, just the man to

take along if there was to be any fighting. He had, however, very

little to add to the solution of the mystery, apparently

believing in the chauffeur-and-maid theory.

It was too late to do anything more that night, and we sat on the Verplancks' porch, overlooking the beautiful harbor. It was a black, inky night, with no moon—one of those nights when the myriad lights on the boats were mere points in the darkness. As we looked out over the water, considering the case which, as yet, we had scarcely started on, Kennedy seemed engrossed in the study in black.

"I thought I saw a moving light for an instant across the bay, above the boats, and as though it were in the darkness of the hills on the other side. Is there a road over there, above the Carter house?" he asked suddenly.

"I thought I saw a moving light for an instant across the bay, above the boats.

"There is a road part of the way on the crest of the hill," replied Mrs. Verplanck. "You can see a car on it, now and then, through the trees, like a moving light."

"Over there, I mean," reiterated Kennedy, indicating the light as it flashed now faintly, then disappeared, to reappear farther along, like a gigantic firefly.

"N-no," said Verplanck. "I don't think the road runs down so far as that. It is farther up the bay."

"What is it, then?" asked Kennedy, half to himself. "It seems to be traveling rapidly. There—it has gone!"

We continued to watch for several minutes, but it did not reappear. Could it have been a light on the mast of a boat moving rapidly up the bay and perhaps nearer to us than we suspected? Nothing further happened, however, and we retired early, expecting to start with fresh minds on the case in the morning. Several watchmen whom Verplanck employed, both on the shore and along the driveways, were left guarding every possible entrance to the estate.

YET the next morning, as we met in the cheery east

breakfast-room, Verplanck's gardener came in, hat in hand, with

much suppressed excitement.

In his hand he held an orange which he had found in the shrubbery beneath the windows of the house. In it was stuck a long nail and to the nail was fastened a tag.

Kennedy read it quickly.

If this had been a bomb, you and your detectives would never have known what struck you.

Aquaero.

"Good Gad, man!" exclaimed Verplanck, who had read the words over Craig's shoulder. "What do you make of that?"

"Good Gad, man!" exclaimed. Verplanck, who had read the

words over Craig's shoulder. "What do you make of that?"

Kennedy merely shook his head. Mrs. Verplanck was the calmest of all.

"The light!" I cried. "You remember the light? Could it have been a signal to some one on this side of the bay, a signal-light in the woods?"

"Possibly," commented Kennedy, absently, adding: "Robbery with this fellow seems to be an art as carefully strategized as a promoter's plan or a merchant's trade-campaign. I think I'll run over this morning and see if there is trace of anything on the Carter estate."

JUST then the telephone-bell rang insistently. It was McNeill,

much excited, though he had not heard of the orange incident.

Verplanck answered the call.

"Have you heard the news?" asked McNeill. "That fellow must have turned up last night at Belle Aire."

"Belle Aire? Why, man, that's fifty miles away and on the other side of the island. He was here last night," and Verplanck related briefly the find of the morning. "No boat could get around the island in that time, and, as for a car, those roads are almost impassable at night."

"Can't help it," returned McNeill doggedly. "The Halstead estate at Belle Aire was robbed last night. It's spooky, all right."

"Tell McNeill I want to see him—will meet him in the village directly," cut in Craig, before Verplanck had finished.

We bolted a hasty breakfast, and in one of the Verplanck cars hurried to meet McNeill.

"What do you intend doing?" he asked helplessly, as Kennedy finished his recital of the queer doings of the night before.

"I'm going out now to look around the Carter place. Can you come along?"

"Surely," agreed McNeill, climbing into the car. "You know him?"

"No."

"Then I'll introduce you. Queer chap, Carter. He's a lawyer, although I don't think he has much practise except managing his mother's estate."

McNeill settled back in the luxurious car with an exclamation of satisfaction.

"What do you think of Verplanck?" he asked.

"He seems to me to be a very public-spirited man," answered Kennedy discreetly.

That, however, was not what McNeill meant, and he ignored it. And so, for the next ten minutes, we were entertained with a little retail scandal of Westport and Bluffwood, including a tale that seemed to have gained currency that Verplanck and Mrs. Hollingsworth were too friendly to please Mrs. Verplanck. I set the whole thing down to the hostility and jealousy of the townspeople, who misinterpret everything possible in the smart set, although I could not help recalling how quickly she had spoken when we had visited the Hollingsworth house in the Streamline the day before.

Montgomery Carter happened to be at home and, at least openly, interposed no objection to our going about the grounds.

"You see," explained Kennedy, watching the effect of his words as if to note whether Carter himself had noticed anything unusual the night before, "we saw a light moving over here last night. To tell the truth, I half expected you would have a story to add to ours, of a second visit."

Carter smiled. "No objection at all. I'm simply nonplused at the nerve of this fellow coming back again. I guess you've heard what a narrow squeak he had with me. You're welcome to go anywhere, just so long as you don't disturb my study down there in the boat-house. I use that because it overlooks the bay—just the place to study over knotty legal problems."

BACK of, or in front of the Carter house, according as you

fancied it faced the bay or not, was the boat-house, built by

Carter's father, who had been a great yachtsman in his day and

commodore of the club. His son had not gone in much for water

sports and had converted the corner underneath a sort of

observation tower into a law office.

"There has always seemed to me to be something strange about that boat-house since the old man died," remarked McNeill, in a half-whisper, as we left Carter. "He always keeps it locked and never lets anyone go in there."

Kennedy had been climbing the hill back of the house and now paused to look about. Below was the Carter garage.

"By the way," exclaimed McNeill, as if he had at last hit on a great discovery, "Carter has a new chauffeur, a fellow named Wickham. I just saw him driving down to the village. He's a chap that it might pay us to watch—a newcomer, smart as a steel trap, they say, but not much of talker."

"Suppose you take that job—watch him," encouraged Kennedy. "We can't know too much about strangers here, McNeill."

"That's right," agreed the detective; "I'll get a line on him."

"Don't be easily discouraged," added Kennedy, as McNeill started down the hill to the garage. "If he is a fox, he'll try to throw you off the trail. Hang on."

"What was that for?" I asked, as the detective disappeared. "Did you want to get rid of him?"

"Partly," replied Craig, descending slowly, after a long survey of the surrounding country. We had reached the garage, deserted now, except for our own car.

"I'd like to investigate that tower," remarked Kennedy, with a keen look at me, "if it could be done without seeming to violate Mr. Carter's hospitality."

"Well," I observed, my eye catching a ladder beside the garage, "there's a ladder."

He walked over to the automobile, took a little package out, slipped it into his pocket, and a few minutes later we had set the ladder up against the side of the boat-house farthest away from the house. It was the work of only a moment for Kennedy to scale it and prowl across the roof to the tower, while I stood guard at the foot.

"No one has been up there recently," he panted breathlessly, as he rejoined me. "There isn't a sign."

We took the ladder quietly back to the garage; then Kennedy led the way down the shore to a sort of little summer house, cutoff from the boat-house and garage by the trees, though over the top of a hedge one could still see the boat-house tower.

We sat down, and Craig filled his lungs with the good salt air.

"Walter," he said, at length, "I wish you'd take the car and go around to Verplanck's. I don't think you can see the tower through the trees, but I should like to be sure."

I found that it could not be seen, though I tried all over the place and got myself disliked by the gardener and suspected by a watchman with a dog.

It could not have been on the tower of the boat-house that we had seen the light, and I hurried back to Craig to tell him so. But when I returned, I found that he was impatiently pacing the little rustic summer house, no longer interested in what he had sent me to find out.

"What has happened?" I asked eagerly.

"Just come out here and I'll show you something," he replied, leaving the summer-house and approaching the boat-house from the other side of the hedge, on the beach, so that the house itself cut us off from observation at Carter's. "I fixed a lens on the top of that tower when I was up there," he explained, pointing up at it. "It must be about fifty feet high. From there, you see, it throws a reflection down to this mirror. I did it because, through a skylight in the tower, I could read whatever was written by anyone sitting at Carter's desk in the corner under it."

"Read?" I repeated, mystified.

"Yes, by invisible light," he continued. "This invisible-light business, you know, is pretty well understood by this time. I was only repeating what was suggested once by Professor Wood, of Johns Hopkins. Practically all sources of light, you understand, give out more or less ultraviolet light, which plays no part in vision whatever. The human eye is sensitive to but few of the light-rays that reach it, and if our eyes were constituted just the least bit differently, we should have an entirely different set of images.

"But by the use of various devices we can, as it were, translate these ultraviolet rays into terms of what the human eye can see. In order to do it, all the visible light-rays which show us the thing as we see it—the tree green, the sky blue—must be cut off. So, in taking an ultraviolet photograph, a screen must be used which will be opaque to these visible rays and yet will let the ultraviolet rays through' to form the image. That gave Professor Wood a lot of trouble. Glass won't do, for glass cuts off the ultraviolet rays entirely. Quartz is a very good medium, but it does not cut off all the visible light. In fact, there is only one thing that will do the work, and that is metallic silver."

I could not fathom what he was driving at, but the fascination of Kennedy himself was quite sufficient.

"Silver," he went on, "is all right if the objects can be illuminated by an electric spark or some other source rich in the rays. But it isn't entirely satisfactory when sunlight is concerned, for various reasons that I need not bore you with. Professor Wood has worked out a process of depositing nickel on glass. That's it up there," he concluded, wheeling a lower reflector about until it caught the image of the afternoon sun thrown from the lens on the top of the tower.

"You see," he resumed, "that upper lens is concave so that it enlarges tremendously. I can do some wonderful tricks with that."

I had been lighting a cigarette and held a box of safety wind-matches in my hand.

"Give me that match-box," he asked.

He placed it at the foot of the tower. Then he went off, I should say, without exaggeration, a hundred feet.

The lettering on the match-box could be seen in the silvered mirror, enlarged to such a point that the letters were plainly visible.

"Think of the possibilities in that!" he added excitedly. "I saw them at once. You can read what some one is writing at a desk a hundred, perhaps two hundred feet away."

"Yes," I cried. "What have you found?"

"Some one came into the boat-house while you were away," he said. "He had a note. It read, 'Those new detectives are watching everything. We must have the evidence. You must get those letters tonight, without fail.'"

"Letters—evidence," I repeated. "Who wrote it? Who received it?"

"I couldn't see over the hedge who had entered the boat-house, and by the time I got around here, he was gone."

"Was it Wickham—or intended for Wickham?" I asked.

Kennedy shrugged his shoulders.

"We'll gain nothing by staying here," he said. "There is just one possibility in the case, and I can guard against that only by returning to Verplanck's and getting some of that stuff I brought up here with me."

LATE in the afternoon though it was, after our return, Kennedy

insisted on hurrying from Verplanck's up the bay to the yacht

club—a large building, extending out into the water on made

land, from which ran a long, substantial dock. He had stopped

long enough only to ask Verplanck to lend him the services of his

best mechanician, a Frenchman named Armand.

On the end of the yacht-club dock, Kennedy and Armand set up a large affair which looked like a mortar. I watched curiously.

"What is this?" I asked, finally. "Fireworks?"

"A rocket-mortar of light weight," explained Kennedy, then dropped into French as he explained to Armand its manipulation.

There was a searchlight on the dock.

"You can use that?" queried Kennedy.

"Oh, yes. Mr. Verplanck, he is vice-commodore of the club. Oh, yes, I can use that. Why, monsieur?"

Kennedy had uncovered a round brass case. In it was a four-sided prism of glass, I should have said, cut off the corner of a huge glass cube.

"Look in it," he said.

It certainly was about the most curious piece of crystal gazing I had ever done. Turn the thing any way I pleased, I could see my face in it, just as in an ordinary mirror.

"What do you call it?" Armand asked.

"A triple mirror," replied Kennedy, and again, half in English and half in French, neither of which I could follow, he explained the use of the mirror to the mechanician.

We were returning up the dock, leaving Armand with instructions to be at the club at dusk, when we met McNeill.

"What luck?" asked Kennedy.

"Nothing," he returned. "I had a 'short' shadow and a 'long' shadow at Wickham's heels all day. You know what I mean. Instead of one man, two—the second sleuthing in the other's tracks. If he escaped Number One, Number Two would take it up, and I was ready to move up into Number Two's place. They kept him in sight about all the time. Not a fact. But then, of course, we don't know what he was doing before we took up trailing him. Say," he added, "I have just got word from an agency with which I correspond in New York, that it is reported that a yeggman named 'Australia Mac,' a very daring and clever chap, has been attempting to dispose of some of the goods which we know have been stolen, through one of the worst 'fences' in New York."

"Is that so?" asked Craig, with the mention of Australia Mac showing the first real interest in anything that McNeil had done since we met him. "Anything else?"

"All, so far. I wired for more details immediately."

"Do you know anything about this Australia Mac?"

"Not much. No one does. He's a new man, it seems, to the police here."

"Be here at eight o'clock, McNeill," said Craig, as we left the club for Verplanck's. "If you can find out more about this yegg-man, so much the better."

"Have you made any progress?" asked Verplanck, as we entered the estate a few minutes later.

"Yes," returned Craig, telling only enough to whet his interest. "There's a clue, as I half expected—from New York, too. You can trust Armand?"

"Absolutely."

"Then we shall transfer our activity to the yacht club to-night," was all that Kennedy vouchsafed.

IT was the regular Saturday-night dance at the club: a

brilliant spectacle; faces that radiated pleasure; gowns that,

for striking combinations of color, would have startled a

futurist; music that set the feet tapping irresistibly—a

scene which I shall pass over because it really has no part in

the story.

The fascination of the ballroom was utterly lost on Craig. "Think of all the houses only half guarded about here tonight," he mused, as we joined Armand and McNeill on the end of the dock.

In front of the club was strung out a long line of cars, and at the dock several speedboats of national and international reputation, among them the famous Streamline II, at our instant beck and call. In it Craig had already placed some rather bulky pieces of apparatus, as well as a brass case containing a second triple mirror, like that which he had left with Armand.

With O'Neill, I walked back along the pier, leaving Kennedy with Armand, until we came to the wide porch, where we joined the wallflowers and the rocking-chair fleet. Mrs. Verplanck, I observed, was a beautiful dancer. I picked her out in the throng immediately, dancing with Carter.

McNeill tugged at my sleeve. Without a word, I saw what he meant me to see. Verplanck and Mrs. Hollingsworth were dancing together. Just then, across the porch, I caught sight of Kennedy at one of the wide windows. He was trying to attract Verplanck's attention, and, as he did so, I worked my way through the throng of chatting couples leaving the floor, until I reached him. Verplanck, oblivious, finished the dance, then, seeming to recollect that he had something to attend to, caught sight of us and ran off during the intermission from the gay crowd to which he resigned Mrs. Hollingsworth.

"What is it?" he asked.

"There's that light down the bay," whispered Kennedy.

Instantly Verplanck forgot about the dance. "Where?" he asked.

"In the same place."

I had not noticed, but Mrs. Verplanck, womanlike, had been able to watch several things at once. She had seen us and had joined us.

"Would you like to run down there in the Streamline?" Verplanck asked. "It will only take a few minutes."

"Very much."

"What is it—that light again?" Mrs. Verplanck put in, as she joined us in walking down the dock.

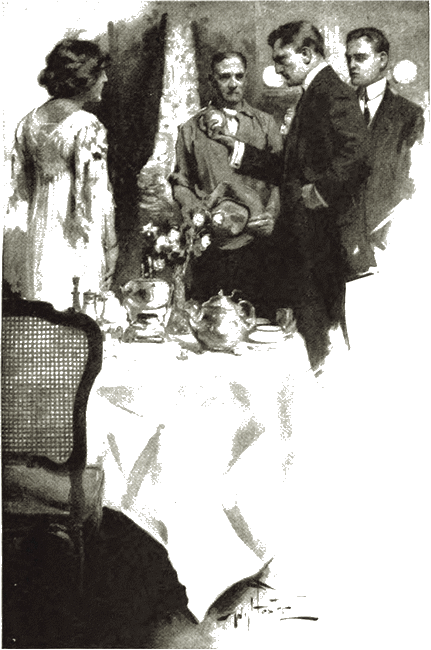

"Yes," answered her husband, pausing to look for a moment at the stuff Kennedy had left with Armand. Mrs. Verplanck leaned over the Streamline, turned as she saw me, and said: "I wish I could go with you. But evening dress is not the thing for a shivery night in a speed-boat. I think I know as much about boats as Mr. Verplanck. Are you going to leave Armand?"

"Evening dress is not the thing for a shivery night in a speed-boat."

"Yes," replied Kennedy, taking his place beside Verplanck, who was seated at the steering wheel. "Walter, and O'Neill—if you two will sit back there, we're ready. All right?"

Armand had cast us off, and Mrs. Verplanck waved from the end of the float as the Streamline quickly shot out into the night. It took her seconds, only, to eat into the miles.

"A little more to port," said Kennedy, as Verplanck swung her around.

JUST then, the steady droning of the engine seemed a bit less

rhythmical. Verplanck throttled her down, but it had no effect.

He shut her off. Something was wrong. As he crawled out into the

space forward of us where the engine was, it seemed as if the

Streamline had broken down suddenly and completely.

Here we were, floundering around in the middle of the bay.

"Chuck-chuck-chuck," came in quick staccato, out of the night. It was Montgomery Carter, alone, on his way across the bay from the club, in his own boat.

"Hello, Carter!" called Verplanck.

"Hello, Verplanck! What's the matter?"

"Don't know. Engine trouble of some kind. Can you give us a line?"

"I've got to go down to the house," he said, ranging up near us. "Then I can take you back. Perhaps I'd better get you out of the way of any other boats, first You don't mind going over and then back?"

Verplanck looked at Craig. "On the contrary," muttered Craig, as he made fast the welcome line.

The Carter dock was some three miles from the club on the other side of the bay. As we came up to it, Carter shut off his engine, bent over it a moment, made fast, and left us with a hurried, "Wait here."

SUDDENLY, overhead, we heard a peculiar whirring noise that

seemed to vibrate through the air. Something huge, black,

monster-like, slid down a board runway into the water, traveled a

few feet, in white suds and spray, rose—and was gone!

As the thing disappeared, I thought I could hear a mocking laugh flung back at us. "What is it?" I asked, straining my eyes at what had seemed, for an instant, like a great flying fish.

"'Aquaero'," quoted Kennedy quickly. "Don't you understand—a hydro-aeroplane—a flying boat. There are hundreds of privately owned flying boats now, wherever there is navigable water. That was the secret of Carter's boat-house, of the light we saw in the air."

"But this Aquaero—who is he?" persisted McNeill. "Carter—Wickham—Australia Mac?"

We looked at each other blankly. No one said a word. We were captured, just as effectively as if we were ironed in a dungeon.

Kennedy had sprung into Carter's boat.

"The deuce!" he exclaimed. "He's put her out of business."

Verplanck, chagrined, had been going over his own engine feverishly. "Do you see that?" he asked suddenly, holding up in the light of a lantern a little nut which he had picked out of the complicated machinery. "It never belonged to this engine. Some one placed it here, knowing it would work its way into a vital part with the vibration."

WHO was the person, the only one who could have done it? The

answer was on my lips, but I repressed it. Mrs. Verplanck herself

had been bending over the engine when last I saw her. All at once

it flashed over me that she knew more about the phantom bandit

than she had admitted. Yet, what possible object could she have,

had in putting the Streamline out of commission?

My mind was working rapidly, piecing together the fragmentary facts. The remark of Kennedy, long before, instantly assumed new significance. What were the possibilities of blackmail in the right sort of evidence? The yeggman had been after what was more valuable than jewels—letters! Whose? Suddenly I saw the situation. Carter had not been robbed at all. He was in league with the robber. That much was a blind, to divert suspicion. He was a lawyer—some one's lawyer. I recalled the message about letters and evidence, and, as I did so, there came to mind a picture of Carter and the woman he had been dancing with. In return for his inside information about the jewels of the wealthy homes of Bluff wood, the yeggman was to get something of interest and importance for his client, Carter.

The situation called for instant action. Yet what could we do, marooned on the other side of the bay?

FROM the club dock, a long finger of light swept out into the

night, plainly enough near the dock, but diffused and disclosing

nothing in the distance. Armand had trained it down the bay in

the direction we had taken, but by the time the beam reached us,

it was so weak that it was lost.

Craig had leaped up on the Carter dock and was capping and uncapping with the brass cover the package which contained the triple mirror.

Still in the distance I could see the wide path of light, aimed toward us but of no avail.

"What are you doing?" I asked.

"Using the triple mirror to signal to Armand. It is something better than wireless. Wireless requires heavy and complicated apparatus. This is portable, heat-less, almost weightless, a source of light depending for its power on another source of light at a great distance."

I wondered how Armand could ever detect its feeble ray.

"Even from a rolling ship," Kennedy continued, alternately covering and recovering the mirror, "the beam of light which this mirror reflects always goes back, unerring, to its source. It would do so from an aeroplane, so high in the air that it could not be located. The returning beam is invisible to anyone not immediately in the path of the ray, and the ray always goes to the observer. It is simply a matter of pure mathematics practically applied. The angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection. There is not the variation of a foot in two miles."

"What message are you sending him?" asked Verplanck.

"To tell Mrs. Hollingsworth to hurry home immediately," Kennedy replied, still flashing the letters according to his code.

"Mrs. Hollingsworth?" repeated Verplanck, looking up.

"Yes. This hydro-aeroplane yeggman is after something besides jewels to-night. Were those letters that were stolen from you the only ones you had in the safe?"

Verplanck looked up quickly. "Why, yes."

"You had none from a woman?"

"No," he almost shouted. Of a sudden, it seemed to dawn on him what Kennedy was driving at—the robbery of his own house, with no loss except of a packet of letters on business, followed by the attempt on Mrs. Hollingsworth. "Do you think I'd keep dynamite, even in the safe?" he added. To hide his confusion, he had turned and was bending again over the engine.

"How is it?" asked Kennedy, his signaling over.

"Able to run on four cylinders and one propeller," replied Verplanck.

"Then let's try her. Watch the engine. I'll take the wheel."

LIMPING along, the engine skipping and missing, the once

peerless Streamline started back across the bay. Instead

of heading toward the club, Kennedy pointed her bow somewhere

between that and Verplanck's.

"I wish Armand would get busy," he remarked, after glancing, now and then, in the direction of the club. "What can be the matter?" "What do you mean?" I asked. There came the boom, as if of a gun far away, in the direction in which he was looking—then another.

"Oh, there it is! Good fellow! I suppose he had to deliver my message to Mrs. Hollingsworth himself first."

From every quarter showed huge balls of fire, rising from the sea, as it were, with a brilliantly luminous flame.

"What is it?" I asked, somewhat startled. "A German invention, for use at night against torpedo and aeroplane attacks. From that mortar Armand has shot half a dozen bombs of phosphide of calcium, which are hurled far into the darkness. They are so constructed that they float, after a short plunge, and are ignited on contact by the action of the salt water itself."

It was a beautiful pyrotechnic display, lighting up the shore and hills of the bay as if by an unearthly flare.

"There's that thing now!" exclaimed Kennedy. In the glow, we could see a peculiar, birdlike figure flying through the air over toward the Hollingsworth house. It was the hydro-aeroplane.

Out from the little stretch of lawn, under the accentuated shadow of the trees, she streaked into the air, swaying from side to side as the pilot operated the stabilizers on the ends of the planes to counteract the puffs of wind off the land.

How could she ever be stopped?

The Streamline, halting and limping though she was, had almost crossed the bay before the light-bombs had been fired by Armand. Every moment brought the flying boat nearer.

She swerved. Evidently the pilot had seen us at last and realized who we were. I was so engrossed, watching the thing, that I had not noticed that Kennedy had given the wheel to Verplanck and was standing in the bow, endeavoring to sight what looked like a huge gun.

In rapid succession half a dozen shots rang out. I fancied I could almost hear the ripping and tearing of the tough rubber-coated silken wings of the hydro-aeroplane, as the wind widened the perforations the gun had made.

She had not been flying high, but now she swooped down almost like a gull, seeking to rest on the water. We were headed toward her now, and, as the flying boat sank, I saw one of the passengers rise, swing his arm, and something splashed in the bay.

On the water, with wings helpless, the flying boat was no match for the Streamline now. She struck at an acute angle, rebounded in the air for a moment, and, with a hiss, skidded along over the waves, planing, with the help of her exhaust, under the step of the boat.

There she was: a hull—narrow, scow-bowed, like a hydroplane—with a long, pointed stern, and a cockpit for two men near the bow. There were two wide, winglike planes, on a light latticework of wood covered with silk, trussed and wired like a kite-frame, the upper plane about five feet above the lower, which was level with the boat deck. We could see the eight-cylindered engine which drove a two-bladed wooden propeller, and over the stern were the air-rudder and the horizontal planes. There she was, the hobbled steed, now, of the phantom bandit.

In spite of everything, however, the flying boat reached the shore a trifle ahead of us. As she did so, both figures in her jumped, and one disappeared quickly up the bank, leaving the other alone.

"Verplanck, McNeill—get him!" cried Kennedy, as our own boat grated on the beach. "Come, Walter; we'll take the other one."

The man had seen that there was no safety in flight. Down the shore, he stood, without a hat, his hair blown pompadour by the wind.

As we approached, Carter turned superciliously, unbuttoning his bulky khaki life-preserver jacket.

"Well?" he asked coolly.

Not for a moment did Kennedy allow the assumed coolness to take him back, knowing that Carter's delay was merely to cover the retreat of the other man.

"So," Craig exclaimed, "you are the—the air-pirate?" Carter disdained to reply.

"It was you who suggested the millionaire households, full of jewels, silver, and gold, only half guarded; you, who knew the habits of the people, you, who traded that information in return for another piece of thievery by your partner, Australia Mac—Wickham, he called himself here in Bluff-wood. It was you—"

A car drove up hastily, and I noted that we were still on the Hollingsworth estate. Mrs. Hollingsworth had seen us and had driven over toward us.

"Montgomery!" she cried, startled.

"Yes," said Kennedy quickly, "air-pirate and lawyer for Mrs. Verplanck in the suit which she contemplated bringing."

Mrs. Hollingsworth grew pale under the ghastly, flickering light from the bay.

"Oh!" she cried, realizing at what Kennedy hinted, "the letters!"

"At the bottom of the harbor, now," said Kennedy. "Mr. Verplanck tells me he has destroyed his. The past is blotted out as far as that is concerned. The future is for you three to determine. For the present, I've caught a yeggman and a blackmailer."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.