RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Cosmopolitan, November 1913, with "The Bomb-Maker"

It is not difficult to tell why these Craig Kennedy stories "get across." Mr. Reeve shows us how all science may ultimately find practical application in detecting crime. It is a new idea, an interesting and fascinating theme. Craig is the most up-to-the-minute character in fiction to-day. A new discovery or invention is announced—Kennedy is right on the job, and makes it a part of his own business equipment. In the story he does some wonderful stunts with new electrical devices and runs a notorious criminal to earth.

"DISTRICT ATTORNEY CARTON wants to see me immediately at the Criminal Courts Building, Walter," announced Kennedy, early one morning. "I know that this is your day of rest. Better come along, though."

Clothed, and as much in my right mind as possible after a late assignment on the Star the night before, I needed no urging, and joined him quickly in a hasty ride down-town in the rush hour.

On the table before the square-jawed, close-cropped, fighting prosecutor, whom I knew already after many a long and hard-fought campaign both before and after election, lay a little package which had evidently come to him in the morning's mail by parcel-post.

"What do you suppose is in that, Kennedy?" he asked, tapping it gingerly. "I haven't opened it yet, but I think it's a bomb. Wait—I'll have a pail of water sent in here so that you can open it, if you will. You understand such things."

"No—no," hastened Kennedy, "that's exactly the wrong thing to do. Some of these modern chemical bombs are set off in precisely that way. No. Let me dissect the thing carefully. I think you may be right. It does look as if it might be an infernal machine. You see the evident disguise of the roughly written address?"

Carton nodded, for it was that that had excited his suspicion in the first place. Meanwhile, Kennedy, without further ceremony, began carefully to remove the wrapper of brown Manila paper, preserving everything as he did so. Carton and I instinctively backed away. Inside, Craig had disclosed an oblong wooden box.

"I realize that opening a bomb is dangerous business," he pursued slowly, engrossed in his work and almost oblivious to us, "but I think I can take a chance safely with this fellow. The dangerous part is what might be called drawing the fangs. No bombs are exactly safe toys to have around until they are wholly destroyed, and before you can say you have destroyed one, it is rather a ticklish business to take out the dangerous element."

He had removed the cover in the deftest manner without friction, and seemingly without disturbing the contents in the least. I do not pretend to know how he did it; but the proof was that we could see him still working from our end of the room.

On the inside of the cover was roughly drawn a skull and cross-bones, showing that the miscreant who sent the thing had at least a sort of grim humor. For, where the teeth should have been in the skull were innumerable match-heads. Kennedy picked them out with as much sang-froid as if he were not playing jackstraws with life and death.

Then he removed the explosive itself and the various murderous slugs and bits of metal embedded in it, carefully separating each as if to be labeled "Exhibit A," "B," and so on for a class in bomb dissection. Finally, he studied the sides and bottom of the box.

"My heavens!" breathed Carton. "I would rather go through a campaign again."

"Evidence of chlorate-of-potash mixture," Kennedy muttered to himself, still examining the bomb. "The inside was a veritable arsenal—a very unusual and clever construction."

We stared at each other in blank awe, at the various parts, so innocent looking in the heaps on the table, now safely separated, but together a combination ticket to perdition.

"Who do you suppose could have sent it?" I blurted out when I found my voice, then, suddenly recollecting the political and legal fight that Carton was engaged in at the time, I added, "The white slavers?"

"Not a doubt," he returned laconically. "And," he exclaimed, bringing down both hands vigorously in characteristic emphasis on the arms of his office chair, "I've got to win this fight against the vice trust, as I call it, or the whole work of the district attorney's office in clearing up the city will be discredited—to say nothing of the risk the present incumbent runs at having such grateful friends about the city send marks of their affection and esteem like this."

I knew something already of the situation, and Carton continued thoughtfully: "All the powers of vice are fighting a last-ditch battle against me now. I think I am on the trail of the man or men higher up in this commercialized-vice business—and it is a business, big business, too. You know, I suppose, that they seem to have a string of hotels in the city, of the worst character. There is nothing that they will stop at to protect themselves. Why, they are using gangs of thugs to terrorize anyone who informs on them. The gunmen, of course, hate a snitch worse than poison. There have been bomb outrages, too—nearly a bomb a day lately—against some of those who look shaky and seem to be likely to do business with my office. But I'm getting closer all the time."

"How do you mean?" asked Kennedy.

"Well, one of the best witnesses, if I can break him down by pressure and promises, ought to be a man named Haddon, who is running a place in the Fifties, known as the Mayfair. Haddon knows all these people. I can get him in half an hour if you think it worth while—not here, but somewhere uptown, say at the Prince Henry."

Kennedy nodded. We had heard of Haddon before, a notorious character in the white-light district. A moment later Carton had telephoned to the Mayfair and had found Haddon.

"How did you get him so that he is even considering turning state's evidence?" asked Craig.

"Well," answered Carton slowly, "I suppose it was partly through a cabaret singer and dancer, Loraine Keith, at the Mayfair. You know you never get the truth about things in the underworld except in pieces. As much as anyone, I think we have been able to use her to weave a web about him. Besides, she seems to think that Haddon has treated her shamefully. According to her story, he seems to have been lavishing everything on her, but lately, for some reason, has deserted her. Still, even in her jealousy she does not accuse any other woman of winning him away."

"Perhaps it is the opposite—another man winning her," suggested Craig dryly.

"It's a peculiar situation," shrugged Carton. "There is another man. As nearly as I can make out there is a fellow named Brodie who does a dance with her. But he seems to annoy her, yet at the same time exercises a sort of fascination over her."

"Then she is dancing at the Mayfair yet?" hastily asked Craig.

"Yes. I told her to stay, not to excite suspicion."

"And Haddon knows?"

"Oh, no. But she has told us enough about him already so that we can worry him, apparently, just as what he can tell us would worry the others interested in the hotels. To tell the truth, I think she is a drug fiend. Why, my men tell me that they have seen her take just a sniff of something and change instantly—become a willing tool."

"That's the way it happens," commented Kennedy.

"Now, I'll go up there and meet Haddon," resumed Carton. "After I have been with him long enough to get into his confidence, suppose you two just happen along."

HALF an hour later Kennedy and I sauntered into the Prince

Henry, where Carton had made the appointment in order to avoid

suspicion that might arise if he were seen with Haddon at the

Mayfair.

The two men were waiting for us—Haddon, by contrast with Carton, a weak-faced, nervous man, with bulgy eyes.

"Mr. Haddon," introduced Carton, "let me present a couple of reporters from the Star—off duty, so that we can talk freely before them, I can assure you. Good fellows, too, Haddon."

The hotel and cabaret keeper smiled a sickly smile and greeted us with a covert, questioning glance.

"This attack on Mr. Carton has unnerved me," he shivered. "If anyone dares to do that to him, what will they do to me?"

"Don't get cold feet, Haddon," urged Carton. "You'll be all right. I'll swing it for you."

Haddon made no reply. At length he remarked: "You'll excuse me for a moment. I must telephone to my hotel."

He entered a booth in the shadow of the back of the cafe, where there was a slot-machine pay-station. "I think Haddon has his suspicions," remarked Carton, "although he is too prudent to say anything yet." A moment later he returned. Something seemed to have happened. He looked less nervous. His face was brighter and his eyes clearer. What was it, I wondered? Could it be that he was playing a game with Carton and had given him a double-cross? I was quite surprised at his next remark.

"Carton," he said confidently, "I'll stick."

"Good," exclaimed the district attorney, as they fell into a conversation in low tones.

"By the way," drawled Kennedy, "I must telephone to the office in case they need me."

He had risen and entered the same booth.

Haddon and Carton were still talking earnestly. It was evident that, for some reason, Haddon had lost his former halting manner. Perhaps, I reasoned, the bomb episode had, after all, thrown a scare into him, and he felt that he needed protection against his own associates, who were quick to discover such dealings as Carton had forced him into. I rose and lounged back to the booth and Kennedy.

"Whom did he call?" I whispered, when

Craig emerged perspiring from the booth, for I knew that that was his purpose.

Craig glanced at Haddon, who now seemed absorbed in talking to Carton. "No one," he answered quickly. "Central told me there had not been a call from this pay-station for half an hour."

"No one?" I echoed almost incredulously. "Then what did he do? Something happened, all right."

Kennedy was evidently engrossed in his own thoughts, for he said nothing.

"Haddon says he wants to do some scouting about," announced Carton, when we rejoined them. "There are several people whom he says he might suspect. I've arranged to meet him this afternoon to get the first part of this story about the inside working of the vice trust, and he will let me know if anything develops then. You will be at your office?"

"Yes, one or the other of us," returned Craig, in a tone which Haddon could not hear.

IN the mean time we took occasion to make some inquiries of

our own about Haddon and Loraine Keith. They were evidently well

known in the select circle in which they traveled. Haddon had

many curious characteristics, chief of which to interest Kennedy

was his speed mania. Time and again he had been arrested for

exceeding the speed limit in taxi-cabs and in a car of his own,

often in the past with Loraine Keith, but lately alone.

It was toward the close of the afternoon that Carton called up hurriedly. As Kennedy hung up the receiver, I read on his face that something had gone wrong.

"Haddon has disappeared," he announced, "mysteriously and suddenly, without leaving so much as a clue. It seems that he found in his office a package exactly like that which was sent to Carton earlier in the day. He didn't wait to say anything about it, but left. Carton is bringing it over here."

Perhaps a quarter of an hour later, Carton himself deposited the package on the laboratory table with an air of relief. We looked eagerly. It was addressed to Haddon at the Mayfair in the same disguised handwriting and was done up in precisely the same fashion.

"Lots of bombs are just scare bombs," observed Craig. "But you never can tell."

Again Kennedy had started to dissect.

"Ah," he went on, "this is the real thing, though, only a little different from the other. A dry battery gives a spark when the lid is slipped back. See, the explosive is in a steel pipe. Sliding the lid off is supposed to explode it. Why, there is enough explosive in this to have silenced a dozen Haddons."

"Do you think he could have been kidnaped or murdered?" I asked. "What is this, anyhow—gang-war?"

"Or perhaps bribed?" suggested Carton.

"I can't say," ruminated Kennedy. "But I can say this: that there is at large in this city a man of great mechanical skill and practical knowledge of electricity and explosives. He is trying to make sure of hiding something from exposure. We must find him."

"And especially Haddon," Carton added quickly. "He is the missing link. His testimony is absolutely essential to the case I am building up."

"I think I shall want to observe Loraine Keith without being observed," planned Kennedy, with a hasty glance at his watch. "I think I'll drop around at this Mayfair I have heard so much about. Will you come?"

"I'd better not," refused Carton. "You know they all know me, and everything quits wherever I go. I'll see you soon."

AS we drove in a cab over to the Mayfair, Kennedy said

nothing. I wondered how and where Haddon had disappeared. Had the

powers of evil in the city learned that he was weakening and

hurried him out of the way at the last moment? Just what had

Loraine Keith to do with it? Was she in any way responsible? I

felt that there were, indeed, no bounds to what a jealous woman

might dare.

Beside the ornate grilled doorway of the carriage entrance of the Mayfair stood a gilt-and-black easel with the words, "Tango Tea at Four." Although it was considerably after that time, there was a line of taxi-cabs before the place and, inside, a brave array of late-afternoon and early-evening revelers. The public dancing had ceased, and a cabaret had taken its place.

We entered and sat down at one of the more inconspicuous of the little round tables. On a stage, at one side, a girl was singing one of the latest syncopated airs.

"We'll just stick around a while, Walter," whispered Craig. "Perhaps this Loraine Keith will come in."

Behind us, protected both by the music and the rustle of people coming am going, a couple talked in low tones. Now and then a word floated over to me in a language which was English, sure enough, but not of a kind that I could understand.

"Dropped by a flatty," I caught once, then something about a "mouthpiece," and the "bulls," and "making a plant."

"A dip—pickpocket—and his girl, or gun-moll, as they call them," translated Kennedy. "One of their number has evidently been picked up by a detective and he looks to them for a good lawyer, or mouthpiece."

Besides these two there were innumerable other interesting glimpses into the life of this meeting-place for the half- and underworlds. A motion in the audience attracted me, as if some favorite performer were about to appear, and heard the "gun-moll" whisper, "Loraine Keith."

There she was, a petite, dark-haired, snappy-eyed girl, chic, well groomed, and gowned so daringly that every woman in the audience envied and every man craned his neck to see her better. Loraine wore a tight-fitting black dress, slashed to the knee. In fact, everything was calculated to set her off at best advantage, and on the stage, at least, there was something recherchée about her. Yet, there was also something gross about her, too.

Accompanying her was a nervous-looking fellow whose washed-out face was particularly unattractive. It seemed as if the bone in his nose was going, due to the shrinkage of the blood vessels. Once, just before the dance began, I saw him rub some thing on the back of his hand, raise it to his nose, and sniff. Then he took a sip of a liqueur.

THE dance began, wild from the first step, and as it

developed, Kennedy leaned over and whispered, "The danse des

Apaches."

It was acrobatic. The man expressed brutish passion and jealousy; the woman, affection and fear. It seemed to tell a story—the struggle of love, the love of the woman against the brutal instincts of the thug, her lover. She was terrified as well as fascinated by him in his mad temper and tremendous super-human strength. I wondered if the dance portrayed the fact.

The music was a popular air with many rapid changes, but through all there was a constant rhythm which accorded well with the abandon of the swaying dance. Indeed, I could think of nothing so much as of Bill Sikes and Nancy as I watched these two.

It was the fight of two frenzied young animals. He would approach stealthily, seize her, and whirl her about, lifting her to his shoulder. She was agile, docile, and fearful. He untied a scarf and passed it about her; she leaned against it, and they whirled giddily about. Suddenly, it seemed that he became jealous. She would run; he follow and catch her. She would try to pacify him; he would become more enraged. The dance became faster and more furious. His violent efforts seemed to be to throw her to the floor, and her streaming hair now made it seem more like a fight than a dance. The audience hung breathless. It ended with her dropping exhausted, a proper finale to this lowest and most brutal dance.

Panting, flushed, with an unnatural light in their eyes, they descended to the audience and, scorning the roar of applause to repeat the performance, sat at a little table.

I saw a couple of girls come over toward the man.

"Give us a deck, Coke," said one, in a harsh voice.

He nodded. A silver quarter gleamed momentarily from hand to hand, and he passed to one girl stealthily a small white-paper packet. Others came to him, both men and women. It seemed to be an established thing.

"Who is that?" asked Kennedy, in a low tone, of the pickpocket back of us.

"Coke Brodie," was the laconic reply.

"A cocaine friend?"

"Yes, and a lobbygow for the grapevine system of selling the dope under this new law."

"Where does he get the supply to sell?" asked Kennedy, casually.

The pickpocket shrugged his shoulders.

"No one knows, I suppose," Kennedy commented to me. "But he gets it in spite of the added restrictions and peddles it in little packets, adulterated, and at a fabulous price for such cheap stuff. The habit is spreading like wildfire. It is a fertile means of recruiting the inmates in the vice-trust hotels. A veritable epidemic it is, too. Cocaine is one of the most harmful of all habit-forming drugs. It used to be a habit of the underworld, but now it is creeping up, and gradually and surely reaching the higher strata of society. One thing that causes its spread is the ease with which it can be taken. It requires no smoking-dens, no syringe, no paraphernalia—only the drug itself."

Another singer had taken the place of the dancers. Kennedy leaned over and whispered to the dip,

"Say, do you and your gun-moll want to pick up a piece of change to get that mouthpiece I heard you talking about?"

Kennedy leaned over and whispered to the dip.

The pickpocket looked at Craig suspiciously.

"Oh, don't worry; I'm all right," laughed Craig. "You see that fellow, Coke Brodie? I want to get something on him. If you will frame that sucker to get away with a whole front, there's a fifty in it."

The dip looked, rather than spoke, his amazement. Apparently Kennedy satisfied his suspicions.

"I'm on," he said quickly. "When he goes, I'll follow him. You keep behind us, and we'll deliver the goods."

"What's it all about?" I whispered.

"Why," he answered, "I want to get Brodie, only I don't want to figure in the thing so that he will know me or suspect anything but a plain hold-up. They will get him; take everything he has. There must be something on that man that will help us."

SEVERAL performers had done their turns, and the supply of the

drug seemed to have been exhausted. Brodie rose and, with a nod

to Loraine, went out, unsteadily, now that the effect of the

cocaine had worn off. One wondered how this shuffling person

could ever have carried through the wild dance. It was not Brodie

who danced. It was the drug.

The dip slipped out after him, followed by the woman. We rose and followed also. Across the city Brodie slouched his way, with an evident purpose, it seemed, of replenishing his supply and continuing his round of peddling the stuff.

He stopped under the brow of a thickly populated tenement row on the upper East Side, as though this was his 'destination. There he stood at the gate that led down to a cellar, looking up and down as if wondering whether he was observed. We had slunk into a doorway.

A woman coming down the street, swinging a chatelaine, walked close to him, spoke, and for a moment they talked.

"It's the gun-moll," remarked Kennedy. "She's getting Brodie off his guard. This must be the root of that grapevine system, as they call it."

Suddenly from the shadow of the next house a stealthy figure sprang out on Brodie. It was our dip, a dip no longer but a regular stick-up man, with a gun jammed into the face of his victim and a broad hand over his mouth. Skilfully the woman went through Brodie's pockets, her nimble fingers missing not a thing.

"Now—beat it," we heard the dip whisper hoarsely, "and if you raise a holler, we'll get you right, next time."

Brodie fled as fast as his weakened nerves would permit his shaky limbs to move. As he disappeared, the dip sent something dark hurtling over the roof of the house across the street and hurried toward us.

"What was that?" I asked.

"I think it was the pistol on the end of a stout cord. That is a favorite trick of the gunmen after a job. It destroys at least a part of the evidence. You can't throw a gun very far alone, you know. But with it at the end of a string you can lift it up over the roof of a tenement. If Brodie squeals to a copper and these people are caught, they can't hold them under the pistol law, anyhow."

The dip had caught sight of us, with his ferret eyes, in the doorway. Quickly Kennedy passed over the money in return for the motley array of objects taken from Brodie. The dip and his gun-moll disappeared into the darkness as quickly as they had emerged.

THERE was a curious assortment—the paraphernalia of a

drug fiend, old letters, a key, and several other useless

articles. The pickpocket had retained the money from the sale of

the dope as his own particular honorarium.

"Brodie has led us up to the source of his supply," remarked Kennedy, thoughtfully regarding the stuff. "And the dip has given us the key to it. Are you game to go in?"

A glance up and down the street showed it still deserted. We wormed our way in the shadow to the cellar before which Brodie had stood. The outside door was open. We entered, and Craig stealthily struck a match, shading it in his hands.

At one end we were confronted by a little door of mystery, barred with iron and held by an innocent enough looking padlock. It was this lock, evidently, to which the key fitted, opening the way into the subterranean vault of brick and stone.

Kennedy opened it and pushed back the door. There was a little square compartment, dark as pitch and delightfully cool and damp. He lighted a match, then hastily blew it out and switched on an electric bulb which it disclosed.

"Can't afford risks like that here," he exclaimed, carefully disposing of the match, as our eyes became accustomed to the light.

On every side were pieces of gas-pipe, boxes, and paper, and on shelves were jars of various materials. There was a work-table littered with tools, pieces of wire, boxes, and scraps of metal.

"My word!" exclaimed Kennedy, as he surveyed the curious scene before us, "this is a regular bomb factory—one of the most amazing exhibits that the history of crime has ever produced."

I followed him in awe as he made a hasty inventory of what we had discovered. There were as many as a dozen finished and partly finished infernal machines of various sizes and kinds, some of tremendous destructive capacity. Kennedy did not even attempt to study them. All about were high explosives, chemicals, dynamite. There was gunpowder of all varieties, antimony, blasting-powder, mercury cyanide, chloral hydrate, chlorate of potash, samples of various kinds of shot, some of the outlawed soft-nosed dumdum bullets, cartridges, shells, pieces of metal purposely left with jagged edges, platinum, aluminium, iron, steel—a conglomerate mass of stuff that would have gladdened an anarchist.

Kennedy was examining a little quartz-lined electric furnace, which was evidently used for heating soldering-irons and other tools. Everything had been done, it seemed, to prevent explosions. There were no open lights and practically no chance for heat to be communicated far among the explosives. Indeed, everything had been arranged to protect the operator himself in his diabolical work.

Kennedy had switched on the electric furnace, and from the various pieces of metal on the table selected several. These he was placing together in a peculiar manner, and to them he attached some copper wire which lay in a corner in a roll.

Under the work-table, beneath the furnace, one could feel the warmth of the thing slightly. Quickly he took the curious affair, which he had hastily shaped, and fastened it under the table at that point, then led the wires out through a little barred window to an air-shaft, the only means of ventilation of the place except the door.

While he was working I had been gingerly inspecting the rest of the den. In a corner, just beside the door, I had found a set of shelves and a cabinet. On both were innumerable packets done up in white paper. I opened one and found it contained several pinches of a white, crystalline substance.

"Little portions of cocaine," commented Kennedy, when I showed him what I had found. "In the slang of the fiends, 'decks.'"

On the top of the cabinet he discovered a little enameled box, much like a snuff-box, in which were also some of the white flakes. Quickly he emptied them out and replaced them with others from jars which had not been made up into packets.

"Why, there must be hundreds of ounces of the stuff here, to say nothing of the various things they adulterate it with," remarked Kennedy. "No wonder they are so careful when it is a felony even to have it in your possession in such quantities. See how careful they are about the adulteration, too. You could never tell except from the effect whether it was the pure or only a few-per-cent.-pure article."

Kennedy took a last look at the den, to make sure that nothing had been disturbed that would arouse suspicion.

"We may as well go," he remarked. "To-morrow, I want to be free to make the connection outside with that wire in the shaft."

IMAGINE our surprise, the next morning, when a tap at our door

revealed Loraine Keith herself.

"Is this Professor Kennedy?" she asked, gazing at us with a half-wild expression which she was making a tremendous effort to control. "Because if it is, I have something to tell him that may interest Mr. Carton."

We looked at her curiously. Without her make-up she was pallid and yellow in spots, her hands trembling, cold, and sweaty, her eyes sunken and glistening, with pupils dilated, her breathing short and hurried, restless, irresolute, and careless of her personal appearance.

"Perhaps you wonder how I heard of you and why I have come to you," she went on. "It is because I have a confession to make. I saw Mr. Haddon just before he was—kidnapped."

She seemed to hesitate over the word.

"How did you know I was interested?" asked Kennedy keenly.

"I heard him mention your name with Mr. Carton's."

"Then he knew that I was more than a reporter for the Star," remarked Kennedy. "Kidnapped, you say? How?"

She shot a glance half of suspicion, half of frankness, at us.

"That's what I must confess. Whoever did it must have used me as a tool. Mr. Haddon and I used to be good friends—I would be yet."

There was evident feeling in her tone which she did not have to assume. "All I remember yesterday was that, after lunch, I was in the office of the Mayfair when he came in. On his desk was a package. I don't know what has become of it. But he gave one look at it, seemed to turn pale, then caught sight of me. 'Loraine,' he whispered, 'we used to be good friends. Forgive me for turning you down. But you don't understand. Get me away from here—come with me—call a cab.'

"Well, I got into the cab with him. We had a chauffeur whom we used to have in the old days. We drove furiously, avoiding the traffic men. He told the driver to take us to my apartment—and—and that is the last I remember, except a scuffle in which I was dragged from the cab on one side and he on the other."

She had opened her handbag and taken from it a little snuff-box, like that which we had seen in the den.

"I—I can't go on," she apologized, "without this stuff."

"So you are a cocaine fiend, also?" remarked Kennedy.

"Yes, I can't help it. There is an indescribable excitement to do something great, to make a mark, that goes with it. It's soon gone, but while it lasts I can sing and dance, do anything until every part of my body begins crying for it again. I was full of the stuff when this happened yesterday; had taken too much, I guess."

The change in her after she had snuffed some of the crystals was magical. From a quivering wretch she had become now a self-confident neurasthenic.

"You know where that stuff will land you, I presume?" questioned Kennedy.

"I don't care," she laughed hollowly. "Yes, I know what you are going to tell me. Soon I'll be hunting for the cocaine bug, as they call it, imagining that in my skin, under the flesh, are worms crawling, perhaps see them, see the little animals running around and biting me. Oh, you don't know. There are two souls to the cocainist. One is tortured by the suffering which the stuff brings; the other laughs at the fears and pains. But it brings such thoughts! It stimulates my mind, makes it work without, against my will, gives me such visions—oh, I cannot go on. They would kill me if they knew I had come to you. Why have I? Has not Haddon cast me off? What is he to me, now?"

It was evident that she was growing hysterical. I wondered whether, after all, the story of the kidnaping of Haddon might not be a figment of her brain, simply an hallucination due to the drug.

"They?" inquired Kennedy, observing her narrowly. "Who?"

"I can't tell. I don't know. Why did I come? Why did I come?"

She was reaching again for the snuff-box, but Kennedy restrained her.

"Miss Keith," he remarked, "you are concealing something from me. There is some one," he paused a moment, "whom you are shielding."

"No, no," she cried. "He was taken. Brodie had nothing to do with it, nothing. That is what you mean. I know. This stuff increases my sensitiveness. Yet I hate Coke Brodie—oh—let me go. I am all unstrung. Let me see a doctor. To-night, when I am better, I will tell all."

Loraine Keith had torn herself from him, had instantly taken a pinch of the fatal crystals, with that same ominous change from fear to self-confidence. What had been her purpose in coming at all? It had seemed at first to implicate Brodie, but she had been quick to shield him when she saw that danger. I wondered what the fascination might be which the wretch exercised over her.

"To-night—I will see you to-night," she cried, and a moment later she was gone, as unexpectedly as she had come.

I looked at Kennedy blankly.

"What was the purpose of that outburst?" I asked.

"I can't say," he replied. "It was all so incoherent that, from what I know of drug fiends, I am sure she had a deep-laid purpose in it all. It does not change my plans."

TWO hours later we had paid a deposit on an empty flat in the

tenement-house in which the bomb-maker had his headquarters, and

had received a key to the apartment from the janitor. After

considerable difficulty, owing to the narrowness of the

air-shaft, Kennedy managed to pick up the loose ends of the wire

which had been led out of the little window at the base of the

shaft, and had attached it to a couple of curious arrangements

which he had brought with him. One looked like a large taximeter

from a motor cab; the other was a diminutive gas-meter, in looks

at least. Attached to them were several bells and lights.

He had scarcely completed installing the thing, whatever it was, when a gentle tap at the door startled me. Kennedy nodded, and I opened it. It was Carton.

"I have had my men watching the Mayfair," he announced. "There seems to be a general feeling of alarm there, now. They can't even find Loraine Keith. Brodie, apparently, has not shown up in his usual haunts since the episode of last night."

"I wonder if the long arm of this vice trust could have reached out and gathered them in, too?" I asked.

"Quite likely," replied Carton, absorbed in watching Kennedy. "What's this?"

A little bell had tinkled sharply, and a light had flashed up on the attachments to the apparatus.

"Nothing. I was just testing it to see if it works. It does, although the end which I installed down below was necessarily only a makeshift. It is not this red light with the shrill bell that we are interested in. It is the green light and the low-toned bell. This is a thermopile."

"And what is a thermopile?" queried Carton.

"For the sake of one who has forgotten his physics," smiled Kennedy, "I may say this is only another illustration of how all science ultimately finds practical application. You probably have forgotten that when two half-rings of dissimilar metals are joined together and one is suddenly heated or chilled, there is produced at the opposite connecting point a feeble current which will flow until the junctures are both at the same temperature. You might call this a thermo-electric thermometer, or a telethermometer, or a microthermometer, or any of a dozen names."

"Yes," I agreed mechanically, only vaguely guessing at what he had in mind.

"The accurate measurement of temperature is still a problem of considerable difficulty," he resumed, adjusting the thermometer. "A heated mass can impart vibratory motion to the ether which fills space, and the wave-motions of ether are able to reproduce in other bodies motions similar to those by which they are caused. At this end of the line I merely measure the electromotive force developed by the difference in temperature of two similar thermo-electric junctions, opposed. We call those junctions in a thermopile 'couples,' and by getting the recording instruments sensitive enough, we can measure one one-thousandth of a degree.

"Becquerel was the first, I believe, to use this property. But the machine which you see here was one recently invented for registering the temperature of sea water so as to detect the approach of an iceberg. I saw no reason why it should not be used to measure heat as well as cold.

"You see, down there I placed the couples of the thermopile beneath the electric furnace on the table. Here I have the mechanism operated by the feeble current from the thermopile, opening and closing switches, and actuating bells and lights. Then, too, I have the recording instrument. The thing is fundamentally very simple and is based on well-known phenomena. It is not uncertain and can be tested at any time, just as I did then, when I showed a slight fall in temperature. Of course it is not the slight changes I am after, not the gradual but the sudden changes in temperature."

"I see," said Carton. "If there is a drop, the current goes one way and we see the red light; a rise and it goes the other, and we see a green light."

"Exactly," agreed Kennedy. "No one is going to approach that chamber down-stairs as long as he thinks anyone is watching, and we do not know where they are watching. But the moment any sudden great change is registered, such as turning on that electric furnace, we shall know it here."

IT must have been an hour that we sat there discussing the

merits of the case and speculating on the strange actions of

Loraine Keith.

Suddenly the red light flashed out brilliantly.

"What's that?" asked Carton quickly.

"I can't tell, yet," remarked Kennedy. "Perhaps it is nothing at all. Perhaps it is a draught of cold air from opening the door. We shall have to wait and see."

We bent over the little machine, straining our eyes and ears to catch the visual and audible signals which it gave.

Gradually the light faded, as the thermopile adjusted itself to the change in temperature.

Suddenly, without warning, a low-toned bell rang before us and a bright-green light flashed up.

"That can have only one meaning," cried Craig excitedly. "Some one is down there in that inferno—perhaps the bomb-maker himself."

The bell continued to ring and the light to glow, showing that whoever was there had actually started the electric furnace. What was he preparing to do? I felt that, even though we knew there was some one there, it did us little good. I, for one, had no relish for the job of bearding such a lion in his den.

We looked at Kennedy, wondering what he would do next. From the package in which he had brought the two registering machines he quietly took another package, wrapped up, about eighteen inches long and apparently very heavy. As he did so he kept his attention fixed on the telethermometer. Was he going to wait until the bomb-maker had finished what he had come to accomplish?

It was perhaps fifteen minutes after our first alarm that the signals began to weaken.

"Does that mean that he has gone—escaped?" inquired Carton anxiously.

"No. It means that his furnace is going at full power and that he has forgotten it. It is what I am waiting for. Come on."

Seizing the package as he hurried from the room, Kennedy hurried out on the street and down the outside cellar stairs, followed by us.

He paused at the thick door and listened. Apparently there was not a sound from the other side, except a whir of a motor and a roar which might have been from the furnace. Softly he tried the door. It was locked on the inside.

Was the bomb-maker there still? He must be. Suppose he heard us. Would he hesitate a moment to send us all to perdition along with himself?

How were we to get past that door? Really, the deathlike stillness on the other side was more mysterious than would have been the detonation of some of the criminal's explosive.

Kennedy had evidently satisfied himself on one point. If we were to get into that chamber we must do it ourselves, and we must do it quickly.

From the package which he carried he pulled out a stubby little cylinder, perhaps eighteen inches long, very heavy, with a short stump of a lever projecting from one side. Between the stonework of a chimney and the barred door he laid it horizontally, jamming in some pieces of wood to wedge it tighter.

Then he began to pump on the handle vigorously. The almost impregnable door seemed slowly to bulge. Still there was no sign of life from within. Had the bomb-maker left before we arrived?

"This is my scientific sledge-hammer," panted Kennedy, as he worked the little lever backward and forward more quickly— "a hydraulic ram. There is no swinging of axes or wielding of crowbars necessary in breaking down an obstruction like this, nowadays. Such things are obsolete. This little jimmy, if you want to call it that, has a power of ten tons. That ought to be enough."

It seemed as if the door were slowly being crushed in before the irresistible ten-ton punch of the hydraulic ram.

Kennedy stopped. Evidently he did not dare to crush the door in altogether. Quickly he released the ram and placed it vertically. Under the now-yawning door-jamb he inserted a powerful claw of the ram and again he began to work the handle.

A moment later the powerful door buckled, and Kennedy deftly swung it outward so that it fell with a crash on the cellar floor.

As the noise reverberated, there came a sound of a muttered curse from the cavern. Some one was there.

We pressed forward.

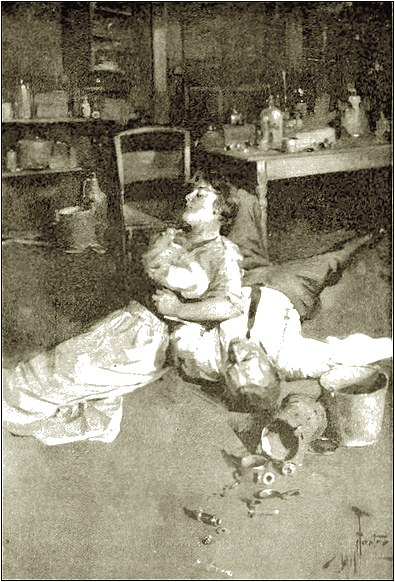

On the floor, in the weird glare of the little furnace, lay a man and a woman, the light playing over their ghastly, set features.

On the floor, in the weird glare of the little furnace, lay a man and a woman.

Kennedy knelt over the man, who was nearest the door.

"Call a doctor, quick," he ordered, reaching over and feeling the pulse of the woman, who had half fallen out of her chair. "They will be all right soon. They took what they thought was their usual adulterated cocaine—see, here is the box in which it was. Instead, I filled the box with the pure drug. They'll come around. Besides, Carton needs both of them in his fight."

"Don't take any more," muttered the woman, half conscious. "There's something wrong with it, Haddon."

I looked more closely at the face in the half-darkness.

It was Haddon himself.

"I knew he'd come back when the craving for the drug became intense enough," remarked Kennedy.

CARTON looked at Kennedy in amazement. Haddon was the last

person in the world whom he had evidently expected to discover

here.

"How—what do you mean?"

"The episode of the telephone booth gave me the first hint. That is the favorite stunt of the drug fiend—a few minutes alone, and he thinks no one is the wiser about his habit. Then, too, there was the story about his speed mania. That is a frequent failing of the cocainist. The drug, too, was killing his interest in Loraine Keith—that is the last stage. Yet under its influence, just as with his lobbygow and lieutenant, Brodie, he found power and inspiration. With him it took the form of bombs to protect himself in his graft."

"He can't—escape this time—Loraine. We'll leave it—at his house—you know—Carton—"

We looked quickly at the work-table. On it was a gigantic bomb of clockwork over which Haddon had been working. The cocaine which was to have given him inspiration had, thanks to Kennedy, overcome him.

Beside Loraine Keith were a suit-case and a Gladstone. She had evidently been stuffing the corners full of their favorite nepenthe, for, as Kennedy reached down and turned over the closely packed woman's finery and the few articles belonging to Haddon, innumerable packets from the cabinet dropped out.

"Hulloa—what's this?" he exclaimed, as he came to a huge roll of bills and a mass of silver and gold coin. "Trying to double-cross us all the time. That was her clever game—to give him the hours he needed to gather what money he could save and make a clean getaway. Even cocaine doesn't destroy the interest of men and women in that," he concluded, turning over to Carton the wealth that Haddon had amassed as one of the meanest grafters of the city of graft.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.