RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Cosmopolitan, September 1913, with "The Death House"

Have you ever served on the jury? Did it happen to be a capital case? Then you know for yourself how much value and importance are usually attached to alleged "expert" testimony. A shrewd lawyer can always make a joke of the best of it. In this story there is expert testimony of a different kind—testimony based upon the most up-to-the-minute scientific discovery which, in the hands of Craig Kennedy, actually delivers the goods and solves a strange murder mystery. Like all the Craig Kennedy stories, this one has the double advantage of telling something new in modern detective methods—and of gripping your interest hard.

"HERE'S a case that begins at the other end, Walter—with the conviction."

Kennedy handed me a letter in the angular hand affected by many women. It was dated at Sing Sing, or rather Ossining. Craig seemed to appreciate the surprise which my face must have betrayed at the curious combination of circumstances.

"Nearly always there is the wife or mother of a condemned man who lives in the shadow of the prison," he remarked quietly, adding, "where she can look down at the grim walls, hoping and fearing."

I said nothing, for the letter spoke for itself.

I have read of your success as a scientific detective and hope that you will pardon me for writing to you, but it is a matter of life or death for one who is dearer to me than all the world.

Perhaps you recall reading of the trial and conviction of my husband, Sanford Godwin, at East Point. The case did not attract much attention in New York papers, although he was defended by an able lawyer from the city.

Since the trial, I have taken up my residence here in Ossining in order to be near him. As I write I can sec the cold, gray walls of the state prison that holds all that is dear to me. Day after day, I have watched and waited, hoped against hope. The courts are so slow, and lawyers are so technical. There have been executions since I came here, too—and I shudder at them. Will his appeal be denied, also?

My husband was accused of murdering by poison—hemlock, they alleged—his adoptive parent, the retired merchant, Parker Godwin, whose family name he took when he was a boy. After the death of the old man, a later will was discovered in which my husband's inheritance was reduced to a small annuity. The other heirs, the Elmores, asserted, and the state made out its case on the assumption, that the new will furnished a motive for killing old Mr. Godwin, and that only by accident had it been discovered.

Sanford is innocent. He could not have done it. It is not in him to do such a thing. I am only a woman, but about some things I know more than all the lawyers and scientists, and I know that he is innocent.

I cannot write all. My heart is too full. Cannot you come and advise me? Even if you cannot take up the case to which I have devoted my life, tell me what to do. I am enclosing a check for expenses, all I can spare at present.

Sincerely yours,

Nella Godwin.

"Are you going?" I asked, watching Kennedy as he tapped the check thoughtfully on the desk.

"I can hardly resist an appeal like that," he replied, replacing the check in the envelope with the letter.

IN the early forenoon, we were on our way by train "up the

river" to Sing Sing, where, at the station, a line of

old-fashioned cabs and red-faced cabbies greeted us, for the town

itself is hilly.

The house to which we had been directed was on the hill, and from its windows one could look down on the barracks-like pile of stone with the evil little black-barred slits of windows, below and perhaps a quarter of a mile away.

There was no need to be told what it was. Its very atmosphere breathed the word "prison." Even the ugly clutter of tall-chimneyed workshops did not destroy it. Every stone, every grill, every glint of a sentry's rifle spelt "prison."

Mrs. Godwin was a pale, slight little woman, in whose face shone an indomitable spirit, unconquered even by the slow torture of her lonely vigil. Except for such few hours that she had to engage in her simple household duties, with now and then a short walk in the country, she was always watching that bleak stone house of atonement.

Yet, though her spirit was unconquered, it needed no physician to tell one that the dimming of the lights at the prison on the morning set for the execution would fill two graves instead of one. For she had come to know that this sudden dimming of the corridor lights, and then their almost as sudden flaring-up, had a terrible meaning, well known to the men inside. Hers was no less an agony than that of the men in the curtained cells, since she had learned that when the lights grow dim at dawn at Sing Sing, it means that the electric power has been borrowed for just that little while to send a body straining against the straps of the electric chair, snuffing out the life of a man.

To-day she had evidently been watching in both directions, watching eagerly the carriages as they climbed the hill, as well as in the direction of the prison.

"How can I ever thank you, Professor Kennedy?" she greeted us at the door, keeping back with difficulty the tears that showed how much it meant to have anyone interest himself in her husband's case.

There was that gentleness about Mrs. Godwin that comes only to those who have suffered much.

"It has been a long fight," she began, as we talked in her modest little sitting-room, into which the sun streamed brightly with no thought of the cold shadows in the grim building below. "Oh, and such a hard, heartbreaking fight! Often it seems as if we had exhausted every means at our disposal, and yet we shall never give up. Why cannot we make the world see our case as we see it? Everything seems to have conspired against us—and yet I cannot, I will not believe that the law and the science that have condemned him are the last words in law and science."

"You said in your letter that the courts were so slow and the lawyers so—"

"Yes, so cold, so technical. They do not seem to realize that a human life is at stake. With them it is almost like a game in which we arc the pawns. And sometimes I fear, in spite of what the lawyers say, that without some new evidence, it—it will go hard with him."

"You have not given up hope in the appeal?" asked Kennedy gently.

"It is merely on technicalities of the law," she replied with quiet fortitude, "that is, as nearly as I can make out from the language of the papers. Our lawyer is Salo Kahn, of the big firm of criminal lawyers, Smith, Kahn & Smith."

"A good lawyer," encouraged Kennedy.

"Yes, I know. He has done all that lawyers can do. But the evidence was—what you would call, scientific—absolutely. Three expert chemists testified for the people that they found the alkaloid, conine, in the body. You see, I have thought and re-thought, read and reread the case so much that I can talk like a—a man about it. Yes, they found the alkaloid in the body and try as he did there was no way that Mr. Kahn could shake their testimony. The jury believed them.

"And yet, oh, Professor Kennedy, is there nothing higher than this cold science of theirs? It cannot be—it cannot be. Sanford has told me the truth, and I know I would know if he had not been telling me what was true."

It was splendid, this exhibition of a woman's faithfulness, of this wife fighting against such tremendous weight of odds, fighting his fight, daring both law and science in her intrepid belief in him.

"Conine," mused Kennedy, half to himself. I could not tell whether he was thinking of what he repeated or of the little woman.

"Yes, the active principle of hemlock," she went on. "That was what the experts discovered, they swore. In the pure state, I believe, it is more poisonous than anything except the cyanides. And it was absolutely scientific evidence. They repeated the tests in court. There was no doubt of it. But, oh, he did not do it. Some one else did it. He did not—he could not."

Kennedy said nothing for a few minutes, but from his tone when he did speak it was evident that he was deeply touched.

"Since our marriage we lived with old Mr. Godwin in the historic Godwin House at East Point," she resumed, as he renewed his questioning. "Sanford—that was my husband's real last name until he came as a boy to work for Mr. Godwin in the office of the factory and was adopted by his employer—Sanford and I kept house for him.

"About a year ago he began to grow feeble and seldom went to the factory, which Sanford managed for him. One night Mr. Godwin was taken suddenly ill. I don't know how long he had been ill before we heard him groaning, but he died almost before we could summon a doctor. There was really nothing suspicious about it, but there had always been a great deal of jealousy of my husband in the town and especially among the few distant relatives of Mr. Godwin. What must have started as an idle, gossipy rumor developed into a serious charge that my husband had hastened his old guardian's death.

"The original will—the will, I call it—had been placed in the safe in the factory several years ago. But when the gossip in the town grew bitter, one day when we were out some private detectives entered the house with a warrant—and they did actually find a will, another will about which we knew nothing, dated later than the first and hidden with some papers in the back of a closet, or sort of fireproof box, built into the wall of the library. The second will was identical with the first in language except that its terms were reversed and instead of being the residuary legatee, Sanford was given a comparatively small annuity, and the Elmores were made residuary legatees instead of annuitants."

"And who are these Elmores?" asked Kennedy curiously.

"There are three, two grandnephews and a grandniece, Bradford, Lambert, and their sister Miriam."

"And they live—"

"In East Point, also. Old Mr. Godwin was not very friendly with his sister, whose grandchildren they were. They were the only other heirs living, and although Sanford never had anything to do with it, I think they always imagined that he tried to prejudice the old man against them."

"I shall want to see the Elmores, or at least some one who represents them, as well as the district attorney up there who conducted the case. But now that I am here, I wonder if it is possible that I could bring any influence to bear to see your husband?"

Mrs. Godwin sighed.

"Once a month," she replied, "I leave this window, walk to the prison, where the warden is very kind to me, and then I can see Sanford. Of course there are the bars between us besides the regular screen. But I can have an hour's talk, and in those talks he has described to me exactly every detail of his life in the—the prison. We have even agreed on certain hours when we think of each other. In those hours I know almost what he is thinking." She paused to collect herself. "Perhaps there may be some way if I plead with the warden. Perhaps—you may be considered his counsel now—you may see him."

A HALF-HOUR later we sat in the big registry room of the

prison and talked with the big-hearted, big-handed warden. Every

argument that Kennedy could summon was brought to bear. He even

talked over long distance with the lawyers in New York. At last

the rules were relaxed and Kennedy was admitted on some

technicality as counsel. Counsel can see the condemned as often

as necessary.

We were conducted down a flight of steps and past huge steel-barred doors, along corridors and through the regular prison until at last we were in what the prison officials call the section for the condemned. Everyone else calls this secret heart of the grim place the death house.

It is made up of two rows of cells, some eighteen or twenty in all, a little more modern in construction than the twelve hundred archaic caverns that pass for cells in the main prison.

At each end of the corridor sat a guard, armed, with eyes never off the rows of cells day or night.

In the wall, on one side, was a door—the little green door—the door from the death house to the death chamber.

While Kennedy was talking to the prisoner, a guard volunteered to show me the death chamber and the "chair." No other furniture was there in the little brick house of one room except this awful chair, of yellow oak, with broad, leather straps. There it stood, the sole article in the brightly varnished room of about twenty-five feet square with walls of clean blue, this grim acolyte of modern scientific death. There were the wet electrodes that are fastened to the legs through slits in the trousers at the calves; above was the pipe-like fixture, like a gruesome helmet of leather that fits over the head, carrying the other electrode.

Back of the condemned was the switch which lets loose a lethal store of energy, and back of that the prison morgue where the bodies are taken. I looked about. In the wall to the left toward the death house was also a door, on this side yellow. Somehow I could not get from my mind the fascination of that door—the threshold of the grave.

Meanwhile Kennedy sat in the little cage and talked with the convicted man across the three-foot distance between cell and screen. I did not see him at that time, but Kennedy repeated afterward what passed, and it so impressed me that I will set it down as if I had been present.

Sanford Godwin was a tall, ashen-faced man, in the prison pallor of whose face was written the determination of despair, a man in whose blue eyes was a queer, half-insane light of hope. One knew that if it had not been for the little woman at the window at the top of the hill, the hope would probably long ago have faded. But this man knew she was always there, thinking, watching, eagerly planning in aid of any new scheme in the long fight for freedom.

"The alkaloid was present, that is certain," he told Kennedy. "My wife has told you that. It was scientifically proved. There is no use in attacking that."

Later on he remarked: "Perhaps you think it strange that one in the very shadow of the death chair"—the word stuck in his throat—"can talk so impersonally of his own case. Sometimes I think it is not my case, but someone else's. And then— that door."

He shuddered and turned away from it. On one side was life, such as it was; on the other, instant death. No wonder he pleaded with Kennedy.

"Why, Walter," exclaimed Craig, as we walked back to the warden's office to telephone to town for a car to take us up to East Point, "whenever he looks out of that cage he sees it. He may close his eyes—and still see it. When he exercises, he sees it. Thinking by day and dreaming by night, it is always there. Think of the terrible hours that man must pass, knowing of the little woman eating her heart out. Is he really guilty? I must find out. If he is not, I never saw a greater tragedy than this slow, remorseless approach of death, in that daily, hourly shadow of the little green door."

EAST POINT was a queer old town on the upper Hudson, with a

varying assortment of industries. Just outside, the old house of

the Godwins stood on a bluff overlooking the majestic river.

Kennedy had wanted to see it before anyone suspected his mission,

and a note from Mrs. Godwin to a friend had been sufficient.

Carefully he went over the deserted and now half-wrecked house, for the authorities had spared nothing in their search for poison, even going over the garden and the lawns in the hope of finding some of the poisonous shrub, hemlock, which it was contended had been used to put an end to Mr. Godwin.

As yet nothing had been done to put the house in order again and, as we walked about, we noticed a pile of old tins in the yard which had not been removed.

Kennedy turned them over with his stick. Then he picked one up and examined it attentively.

"Hm—a blown can," he remarked.

"Blown?" I repeated.

"Yes. When the contents of a tin begin to deteriorate they sometimes give off gases which press out the ends of the tin. You can see how these ends bulge."

OUR next visit was to the district attorney, a young man,

Gordon Kilgore, who seemed not unwilling to discuss the case

frankly.

"I want to make arrangements for disinterring the body," explained Kennedy. "Would you fight such a move?"

"Not at all, not at all," he answered brusquely. "Simply make the arrangements through Kahn. I shall interpose no objection. It is the strongest, most impregnable part of the case, the discovery of the poison. If you can break that down you will do more than anyone else has dared to hope. But it can't be done. The proof was too strong. Of course it is none of my business, but I'd advise some other point of attack."

I must confess to a feeling of disappointment when Kennedy announced after leaving Kilgore that, for the present, there was nothing more to be done at East Point until Kahn had made the arrangements for reopening the grave.

WE motored back to Ossining, and Kennedy tried to be

reassuring to Mrs. Godwin.

"By the way," he remarked, just before we left, "you used a good deal of canned goods at the Godwin house, didn't you?"

"Yes, but not more than other people, I think," she said.

"Do you recall using any that were—well, perhaps not exactly spoiled, but that had anything peculiar about them?"

"I remember once we thought we found some cans that seemed to have been attacked by mice—at least they smelt so, though how mice could get through a tin can we couldn't see."

"Mice?" queried Kennedy. "Had a mousey smell? That's interesting. Well, Mrs. Godwin, keep up a good heart. Depend on me. What you have told me to-day has made me more than interested in your case. I shall waste no time in letting you know when anything encouraging develops."

CRAIG had never had much patience with red tape that barred

the way to the truth, yet there were times when law and legal

procedure had to be respected, no matter how much they hampered,

and this was one of them. At last the order was obtained

permitting the opening again of the grave of old Mr. Godwin. The

body was exhumed, and Kennedy set about his examination of what

secrets it might hide.

Meanwhile, it seemed to me that the suspense was terrible. Kennedy was moving slowly, I thought. Not even the courts themselves could have been more deliberate. Also, he was keeping much to himself.

Still, day after day, there was the slow, inevitable approach of the thing that now, I, too, had come to dread—the handing down of the final decision on the appeal.

Yet what could Craig do otherwise, I asked myself. I had become deeply interested in the case by this time and had read all the evidence, hundreds of pages of it. It was cold, hard, brutal, scientific fact, and as I read I felt that hope faded for the ashen-faced man and the pallid little woman. It seemed the last word in science. Was there any way of escape?

Impatient as I was, I often wondered what must have been the suspense of those to whom the case meant everything.

"How are the tests coming along?" I ventured one night, after Kahn had arranged for the uncovering of the grave.

It was now several days since Kennedy had gone up to East Point to superintend the exhumation and had returned to the city with the materials which had caused him to keep later hours in the laboratory than I had ever known even the indefatigable Craig to spend on a stretch before.

He shook his head doubtfully.

"Walter," he admitted, "I'm afraid I have reached the limit on the line of investigation I had planned at the start."

I looked at him in dismay. "What then?" I managed to gasp.

"I am going up to East Point again tomorrow to look over that house and start a new line. You can go."

NO urging was needed, and the following day saw us again on

the ground. The house, as I have said, had been almost torn to

pieces in the search for the will and the poison evidence. As

before, we went to it unannounced, and this time we had no

difficulty in getting in. Kennedy, who had brought with him a

large package, made his way directly to a sort of drawing-room

next to the large library, in the closet of which the will had

been discovered.

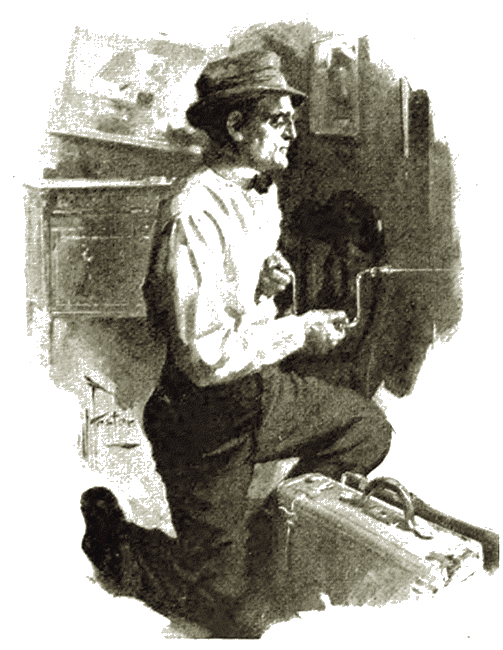

He unwrapped the package and took from it a huge brace and bit, the bit a long, thin, murderous looking affair such as might have come from a burglar's kit. I regarded it much in that light.

"What's the lay?" I asked, as he tapped over the walls to ascertain of just what they were composed.

Without a word he was now down on his knees, drilling a hole in the plaster and lath. When he struck an obstruction he stopped, removed the bit, inserted another, and began again.

Without a word he was now down on his knees,

drilling a hole in the plaster and lath.

"Are you going to put in a detectaphone?" I asked again.

He shook his head. "A detectaphone wouldn't be of any use here," he replied. "No one is going to do any talking in that room."

Again the brace and bit were at work. At last the wall had been penetrated, and he quickly removed every trace from the other side that would have attracted attention to a little hole in an obscure corner of the flowered wall-paper.

Next, he drew out what looked like a long putty-blower, perhaps a foot long and three-eighths of an inch in diameter.

"What's that?" I asked, as he rose after carefully inserting it.

"Look through it," he replied simply, still at work on some other apparatus he had brought.

I looked. In spite of the smallness of the opening at the other end, I was amazed to find that I could see nearly the whole room on the other side of the wall.

"It's a detectascope," he explained, "a tube with a fish-eye lens which I had an expert optician make for me."

"A fish-eye lens?" I repeated.

"Yes. The focus may be altered in range so that anyone in the room may be seen and recognized and any action of his may be detected. The original of this was devised by Gaillard Smith, the adapter of the detectaphone. The instrument is something like the cytoscope, which the doctors use to look into the human interior. Now, look through it again. Do you see the closet?"

Again I looked. "Yes," I said, "but will one of us have to watch here all the time?"

He had been working on a black box in the mean time, and now he began to set it up, adjusting it to the hole in the wall which he enlarged on our side.

"No, that is my own improvement on it. You remember once we used a quick-shutter camera with an electric attachment, which moved the shutter on the contact of a person with an object in the room? Well, this, camera has that quick shutter. But, in addition, I have adapted to the detectascope an invention by Professor Robert Wood, of Johns Hopkins. He has devised a fish-eye camera that 'sees' over a radius of one hundred and eighty degrees—not only straight in front, but over half a circle, every point in that room.

"You know the refracting power of a drop of water. Since it is a globe, it refracts the light which reaches it from all directions. If it is placed like the lens of a camera, as Dr. Wood tried it, so that one half of it catches the light, all the light caught will be refracted through it. Fishes, too, have a wide range of vision. Some have eyes that see over half a circle. So the lens gets its name. Ordinary cameras, because of the flatness of their lenses, have a range of only a few degrees, the widest in use, I believe, taking in only ninety-six, or a little more than a quarter of a circle. So, you see, my detectascope has a range almost twice as wide as that of any other."

Though I did not know what he expected to discover and knew that it was useless to ask, the thing seemed very interesting. Craig did not pause, however, to enlarge on the new machine, but gathered up his tools and announced that our next step would be a visit to a lawyer whom the Elmores had retained as their personal counsel to look after their interests, now that the district attorney seemed to have cleared up the criminal end of the case.

HOLLINS was one of the prominent attorneys of East Point, and

before the election of Kilgore as prosecutor had been his

partner. Unlike Kilgore, we found him especially uncommunicative

and inclined to resent our presence in the case as intruders.

The interview did not seem to me to be productive of anything. In fact, it seemed as if Craig were giving Hollins much more than he was getting.

"I shall be in town over night," remarked Craig. "In fact, I am thinking of going over the library up at the Godwin house soon, very carefully." He spoke casually. "There may be, you know, some finger-prints on the walls around that closet which might prove interesting."

A quick look from Hollins was the only answer. In fact, it was seldom that he uttered more than a monosyllable as we talked over the various aspects of the case.

A half-hour later, when we had left and had gone to the hotel, I asked Kennedy suspiciously, "Why did you expose your hand to Hollins, Craig?"

He laughed. "Oh, Walter," he remonstrated, "don't you know that it is nearly always useless to look for finger-prints, except under some circumstances, even a few days afterward? This is months, not days. Why on iron and steel they last with tolerable certainty only a short time, and not much longer on silver, glass, or wood. But they are seldom permanent unless they are made with ink or blood or something that leaves a more or less indelible mark. That was a 'plant'."

"But what do you expect to gain by it?"

"Well," he replied enigmatically, "no one is necessarily honest."

IT was late in the afternoon when Kennedy again visited the

Godwin house and examined the camera. Without a word he pulled

the detectascope from the wall and carried the whole thing to the

developing-room of the local photographer.

There he set to work on the film and I watched him in silence. He seemed very much excited as he watched the film develop, until at last he held it up, dripping, to the red light.

"Someone has entered that room this afternoon and attempted to wipe off the walls and woodwork of that closet, as I expected," he exclaimed.

"Who was it?" I asked, leaning over.

Kennedy said nothing, but pointed to a figure on the film. I bent closer. It was the figure of a woman.

"Miriam!" I exclaimed in surprise.

I looked aghast at him. If it had been either Bradford or Lambert, all of whom we had come to know since Kennedy had interested himself in the case, or even Hollins or Kilgore, I should not have been surprised. But Miriam!

"How could she have any connection with the case?" I asked incredulously.

Kennedy did not attempt to explain. "It is a fatal mistake, Walter, for a detective to assume that he knows what anybody would do in any given circumstances. The only safe course for him is to find out what the persons in question did do. People are always doing the unexpected. This is a case of it, as you see. I am merely trying to get back at facts. Come; I think we might as well not stay over night, after all. I should like to drop off on the way back to the city to see Mrs. Godwin."

As we rode up the hill I was surprised to see that there was no one at the window, or did anyone seem to pay attention to our knocking at the door.

Kennedy turned the knob quickly and strode in.

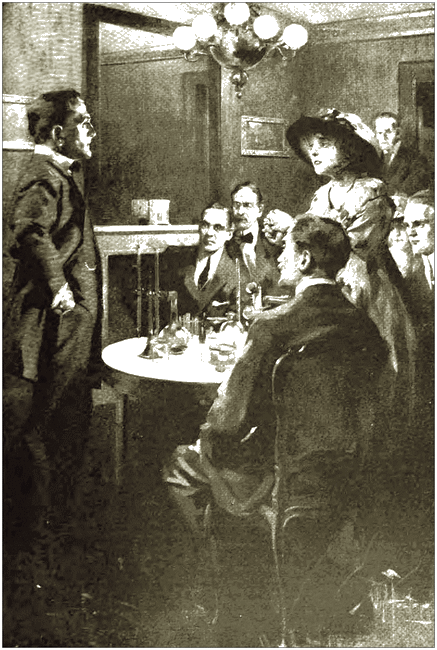

Seated in a chair, as white as a wraith from the grave, was Mrs. Godwin, staring straight ahead, seeing nothing, hearing nothing.

Seated in a chair, as white as a wraith from

the grave, was Mrs. Godwin, staring straight ahead.

"What's the matter?" demanded Kennedy, leaping to her side and grasping her icy hand.

The stare on her face seemed to change slightly as she recognized him.

"Walter—some water—and a little brandy—if there is any. Tell me—what has happened?"

From her lap a yellow telegram had fluttered to the floor, but before he could pick it up, she gasped, "The appeal—it has been denied." Kennedy picked up the paper. It was a message, unsigned, but not from Kahn, as its wording and in fact the circumstances plainly showed.

"The execution is set for the week beginning the twenty-fifth," she continued, in the same hollow, mechanical voice. "My God —that's next Monday!"

She had risen now and was pacing the room.

"No! I'm not going to faint. I wish I could. I wish I could cry. I wish I could do something. Oh, those Elmores—they must have sent it. No one would have been so cruel but them."

She stopped and gazed wildly out of the window at the prison. Neither of us knew what to say for the moment.

"Many times from this window," she cried, "I have seen a man walk out of that prison gate. I always watch to see what he does, though I know it is no use. If he stands in the free air, stops short, and looks up suddenly, taking a long look at every house—I hope. But he always turns for a quick, backward look at the prison and goes half running down the hill. They always stop in that fashion, when the steel door opens outward. Yet I have always looked and hoped. But I can hope no more—no more. The last chance is gone."

"No—not the last chance," exclaimed Craig, springing to her side lest she should fall. Then he added gently, "You must come with me to East Point—immediately."

"What—leave him here—alone—in the last days? No—no—no. Never. I must see him. I wonder if they have told him yet."

It was evident that she had lost faith in Kennedy, in everybody, now.

"Mrs. Godwin," he urged. "Come—you must. It is a last chance."

Eagerly he was pouring out the story of the discovery of the afternoon by the little detectascope.

"Miriam?" she repeated, dazed. "She—know anything—it can't be. No—don't raise a false hope now."

"It is the last chance," he urged again. "Come. There is not an hour to waste now."

THERE was no delay, no deliberation about Kennedy now. He had

been forced out into the open by the course of events, and he

meant to take advantage of every precious moment.

Down the hill our car sped to the town, with Mrs. Godwin still protesting, but hardly realizing what was going on. Regardless of tolls, Kennedy called up his laboratory in New York and had two of his most careful students pack up the stuff which he described minutely to be carried to East Point immediately by train. Kahn, too, was at last found and summoned to meet us there, also.

Miles never seemed longer than they did to us as we tore over the country from Ossining to East Point, a silent party, yet keyed up by an excitement that none of us had ever felt before.

Impatiently we awaited the arrival of the men from Kennedy's laboratory, while we made Mrs. Godwin as comfortable as possible in a room at the hotel. In one of the parlors Kennedy was improvising a laboratory as best he could. Meanwhile, Kahn had arrived, and together we were seeking those whose connection with, or interest in, the case made necessary their presence.

IT was well along toward midnight before the hasty conference

had been gathered; besides Mrs. Godwin, Salo Kahn, and ourselves,

the three Elmores, Kilgore, and Hollins.

Strange though it was, the room seemed to me almost to have assumed the familiar look of the laboratory in New York. There was the same clutter of tubes and jars on the tables, but above all that same feeling of suspense in the air which I had come to associate with the clearing-up of a case. There was something else in the air, too. It was a peculiar mousey smell, disagreeable, and one which made it a relief to have Kennedy begin in a low voice to tell why he had called us together so hastily.

"I shall start," announced Kennedy, "at the point where the state left off—with the proof that Mr. Godwin died of conine, or hemlock poisoning. Conine, as every chemist knows, has a long and well-known history. It was the first alkaloid to be synthesized. Here is a sample, this colorless, oily fluid. No doubt you have noticed the mousey odor in this room. As little as one part of conine to fifty thousand of water gives off that odor—it is characteristic.

"I have proceeded with extraordinary caution in my investigation of this case," he went on. "In fact, there would have been no value in it, otherwise, for the experts for the people seem to have established the presence of conine in the body with absolute certainty."

He paused and we waited expectantly.

"I have had the body exhumed and have repeated the tests. The alkaloid which I discovered had given precisely the same results as in their tests."

My heart sank. What was he doing—convicting the man over again?

"There is one other test which I tried," he continued, "but which I cannot take time to duplicate to-night. It was testified at the trial that conine, the active principle of hemlock, is intensely poisonous. No chemical antidote is known. A fifth of a grain has serious results; a drop is fatal. An injection of a most minute quantity of real conine will kill a mouse, for instance, almost instantly. But the conine which I have isolated in the body is inert!"

It came like a bombshell to the prosecution, so bewildering was the discovery.

"Inert?" cried Kilgore and Hollins almost together. "It can't be. You are making sport of the best chemical experts that money could obtain. Inert? Read the evidence—read the books."

"On the contrary," resumed Craig, ignoring the interruption, "all the reactions obtained by the experts have been duplicated by me. But, in addition, I tried this one test which they did not try. I repeat: the conine isolated in the body is inert."

We were too perplexed to question him. "Alkaloids," he continued quietly, "as you know, have names that end in 'in' or 'ine'—morphine, strychnine, and so on. Now there are two kinds of alkaloids which are sometimes called vegetable and animal. Moreover, there is a large class of which we are learning much which are called the ptomaines—from ptoma, a corpse. Ptomaine poisoning, as everyone knows, results when we eat food that has begun to decay.

"Ptomaines are chemical compounds of an alkaloidal nature formed in protein substances during putrefaction. They are purely chemical bodies and differ from the toxins. There are also what are called leucomaines, formed in living tissues, and when not given off by the body they produce auto-intoxication.

"There are more than three score ptomaines, and half of them are poisonous. In fact, illness due to eating infected foods is much more common than is generally supposed. Often there is only one case in a number of those eating the food, due merely to that person's inability to throw off the poison. Such cases are difficult to distinguish. They are usually supposed to be gastro-enteritis. Ptomaines, as their name shows, are found in dead bodies. They are found in all dead matter after a time, whether it is decayed food or a decaying corpse.

"No general reaction is known by which the ptomaines can be distinguished from the vegetable alkaloids. But we know that animal alkaloids always develop either as a result of decay of food or of the decay of the body itself."

AT one stroke Kennedy had reopened the closed case and had

placed the experts at sea.

"I find that there is an animal conine as well as the true conine," he hammered out. "The truth of this matter is that the experts have confounded vegetable conine with cadaveric conine. That raises an interesting question. Assuming the presence of conine, where did it come from?"

He paused and began a new line of attack. "As the use of canned goods becomes more and more extensive, ptomaine poisoning is more frequent. In canning, the cans are heated. They are composed of thin sheets of iron coated with tin, the seams pressed and soldered with a thin line of solder. They are filled with cooked food, sterilized, and closed. The bacteria are usually all killed, but now and then, the apparatus does not work, and they develop in the can. That results in a 'blown can'—the ends bulge a little bit. On opening, a gas escapes, the food has a bad odor and a bad taste. Sometimes people say that the tin and lead poison them; in practically all cases the poisoning is of bacterial, not metallic, origin. Mr. Godwin may have died of poisoning, probably did. But it was ptomaine poisoning. The blown cans which I have discovered would indicate that."

I was following him closely, yet though this seemed to explain a part of the case, it was far from explaining all.

"Then followed," he hurried on, "the development of the usual ptomaines in the body itself. These, I may say, had no relation to the cause of death itself. The putrefactive germs began their attack. Whatever there may have been in the body before, certainly they produced a cadaveric ptomaine conine. For many animal tissues and fluids, especially if somewhat decomposed, yield not infrequently compounds of an oily nature with a mousey odor, fuming with hydrochloric acid and in short, acting just like conine. There is ample evidence, I have found, that conine or a substance possessing most, if not all, of its properties is at times actually produced in animal tissues by decomposition. And the fact is, I believe, that a number of cases have arisen, in which the poisonous alkaloid was at first supposed to have been discovered which were really mistakes."

The idea was startling in the extreme. Here was Kennedy, as it were, overturning what had been considered the last word in science as it had been laid down by the experts for the prosecution, opinions so impregnable that courts and juries had not hesitated to condemn a man to death.

"There have been cases," Craig went on solemnly, "and I believe this to be one, where death has been pronounced to have been caused by wilful administration of a vegetable alkaloid, which toxicologists would now put down as ptomaine-poisoning cases. Innocent people have possibly already suffered and may in the future. But medical experts—" he laid especial stress on the word—"are much more alive to the danger of mistake than formerly. This was a case where the danger was not considered, either through carelessness, ignorance, or prejudice.

"Indeed, ptomaines are present probably to a greater or less extent in every organ which is submitted to the toxicologist for examination. If he is ignorant of the nature of these substances, he may easily mistake them for vegetable alkaloids. He may report a given poison present when it is not present. It is even yet a new line of inquiry which has only recently been followed, and the information is still comparatively small and inadequate.

"It is very difficult, perhaps impossible, for the chemist to state absolutely that he has detected true conine. Before he can do it, the symptoms and the post-mortem appearance must agree; analysis must be made before, not after, decomposition sets in, and the amount of the poison found must be sufficient to experiment with, not merely to react to a few usual tests.

"What the experts asserted so positively, I would not dare to assert. Was he killed by ordinary ptomaine poisoning, and had conine, or rather its double, developed first in his food along with other ptomaines that were not inert? Or did the cadaveric conine develop only in the body after death? Chemistry alone cannot decide the question so glibly as the experts did. Further proof must be sought. Other sciences must come to our aid."

I WAS sitting next to Mrs. Godwin. As Kennedy's words rang

out, her hand, trembling with emotion, pressed my arm. I turned

quickly to see if she needed assistance. Her face was radiant.

All the fees for big cases in the world could never have

compensated Kennedy for the mute, unrestrained gratitude which

the little woman shot at him.

Kennedy saw it, and in the quick shifting of his eyes to my face, I read that he relied on me to take care of Mrs. Godwin while he plunged again into the clearing up of the mystery.

"I have here the will—the second one," he snapped out, turning and facing the others in the room.

Craig turned a switch in an apparatus which his students had brought from New York. From a tube on the table came a peculiar bluish light.

"This," he explained, "is a source of ultraviolet rays. They are not the bluish light which you see, but rays contained in it which you cannot see.

"Ultraviolet rays have recently been found very valuable in the examination of questioned documents. By the use of a lens made of quartz covered with a thin film of metallic silver, there has been developed a practical means of making photographs by the invisible rays of light above the spectrum—these ultraviolet rays. The quartz lens is necessary, because these rays will not pass through ordinary glass, while the silver film acts as a screen to cut off the ordinary light rays and those below the spectrum. By this means, most white objects are photographed black and even transparent objects like glass are black.

"I obtained the copy of this will, but under the condition from the surrogate that absolutely nothing must be done to it to change a fiber of the paper or a line of a letter. It was a difficult condition. While there are chemicals which are frequently resorted to for testing the authenticity of disputed documents such as wills and deeds, their use frequently injures or destroys the paper under test. So far as I could determine, the document also defied the microscope.

"But ultraviolet photography does not affect the document tested in any way, and it has lately been used practically in detecting forgeries. I have photographed the last page of the will with its signatures, and here it is. What the eye itself cannot see, the invisible light reveals."

He was holding the document and the copy, just an instant, as if considering how to announce with best effect what he had discovered.

"In order to unravel this mystery," he resumed, looking up and facing the Elmores, Kilgore, and Hollins squarely, "I decided to find out whether anyone had had access to that closet where the will was hidden. It was long ago, and there seemed to be little that I could do. I knew it was useless to look for finger-prints.

"So I used what we detectives now call the law of suggestion. I questioned closely one who was in touch with all those who might have had such access. I hinted broadly at seeking finger-prints which might lead to the identity of one who had entered the house unknown to the Godwins, and placed a document where private detectives would subsequently find it under suspicious circumstances.

"Naturally, it would seem to one who was guilty of such an act, or knew of it, that there might, after all, be finger-prints. I tried it. I found out through this little tube, the detectascope, that one really entered the room after that, and tried to wipe off any supposed finger-prints that might still remain. That settled it. The second will was a forgery, and the person who entered that room so stealthily this afternoon knows that it is a forgery."

AS Kennedy slapped down on the table the film from his camera,

which had been concealed, Mrs. Godwin turned her now large and

unnaturally bright eyes and met those of the other woman in the

room.

"Oh—oh—heaven help us—me, I mean!" cried Miriam, unable to bear the strain of the turn of events longer. "I knew there would be retribution—I knew—I knew—"

Mrs. Godwin was on her feet in a moment.

Mrs. Godwin was on her feet in a moment.

"Once my intuition was not wrong, though all science and law was against me," she pleaded with Kennedy. There was a gentleness in her tone that fell like a soft rain on the surging passions of those who had wronged her so shamefully. "Professor Kennedy, Miriam could not have forged—"

Kennedy smiled. "Science was not against you, Mrs. Godwin. Ignorance was against you. And your intuition does not go contrary to science this time, either."

It was a splendid exhibition of fine feeling which Kennedy waited to have impressed on the Elmores, as though burning it into their minds.

"Miriam Elmore knew that her brothers had forged a will and hidden it. To expose them was to convict them of a crime. She kept their secret, which was the secret of all three. She even tried to hide the finger-prints which would have branded her brothers.

"For ptomaine poisoning had unexpectedly hastened the end of old Mr. Godwin. Then gossip and the 'scientists' did the rest. It was accidental, but Bradford and Lambert Elmore were willing to let events take their course and declare genuine the forgery which they had made so skilfully, even though it convicted an innocent man of murder and killed his faithful wife. As soon as the courts can be set in motion to correct an error of science by the truth of later science, Sing Sing will lose one prisoner from the death house and gain two forgers in his place."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.