RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Cosmopolitan, July 1913, with "The Elixir of Life"

There are to-day more ways of taking human life with impunity than were ever known before. And this knowledge is so common that almost any man of intelligence may take advantage of it. Do you remember the recent wonderful discoveries by Dr Carrel, of the Rockefeller Institute? Some of these triumphs of medicine were hailed as universal blessings to mankind, particularly that method of healing which, if perfected, will rob anything but a fatal wound of half its terrors. It would not seem possible for a criminal to profit by such a beneficent discovery; but you must remember that the modern criminal fights with science as science fights him. In this story Craig Kennedy solves a murder mystery that involves a man high up in the professional world, a man who knows the secrets of prolonging life—and of taking it...

"NOT even a blood spot has been disturbed in the kitchen. Nothing has been altered since the discovery of the murdered chef, except that his body has been moved into the next room."

Emery Pitts, one of the "thousand millionaires of steel," overwrought as he was by a murder in his own household in the large Fifth Avenue mansion, sank back in his easy-chair, exhausted.

Pitts was not an old man; indeed, in years he was in the prime of life. Yet by his looks he might almost have been double his age, the more so in contrast with Minna Pitts, his young and very pretty wife, who stood near him in the quaint breakfast-room and solicitously moved a pillow back of his head.

Kennedy and I looked on in amazement. We knew that he had recently retired from active business, giving as a reason his failing health. But neither of us had thought, when the hasty summons came early one morning to visit him immediately at his house, that his condition was as serious as it now appeared.

"In the kitchen?" repeated Kennedy, evidently not prepared for any trouble in that part of the house.

Pitts, who had closed his eyes, now reopened them slowly and I noticed how contracted were the pupils.

"Yes," he answered somewhat wearily, "my private kitchen which I have had fitted up. You know, I am on a diet, have been ever since I offered the one hundred thousand dollars for the sure restoration of youth. I shall have you taken out there presently."

He lapsed again into a half dreamy state, his head bowed on one hand resting on the arm of his chair. The morning's mail still lay on the table, some letters open, as they had been when the discovery had been announced. Mrs. Pitts was apparently much excited and unnerved by the gruesome discovery in the house.

"You have no idea who the murderer might be?" asked Kennedy, addressing Pitts, but glancing keenly at his wife.

"No," replied Pitts, "if I had I should have called the regular police. I wanted you to take it up before they spoiled any of the clues. In the first place we do not think it could have been done by any of the other servants. At least, Minna says that there was no quarrel."

"How could anyone have got in from the outside?" asked Craig.

"There is a back way, a servants' entrance, but it is usually locked. Of course, some one might have obtained a key to it."

Mrs. Pitts had remained silent throughout the dialogue. I could not help thinking that she suspected something, perhaps was concealing something. Yet each of them seemed equally anxious to have the marauder apprehended, whoever he might be.

"My dear," he said to her at length, "will you call some one and have them taken to the kitchen?"

AS Minna Pitts led us through the large mansion preparatory to

turning us over to a servant she explained hastily that Mr. Pitts

had long been ill and was now taking a new treatment under Dr.

Thompson Lord. No one having answered her bell in the present

state of excitement of the house, she stopped short at the

pivoted door of the kitchen, with a little shudder at the

tragedy, and stood only long enough to relate to us the story as

she had heard it from the valet, Edward.

Mr. Pitts, it seemed, had wanted an early breakfast and had sent Edward to order it. The valet had found the kitchen a veritable slaughter-house, with the negro chef, Sam, lying dead on the floor. Sam had been dead, apparently, since the night before.

As she hurried away, Kennedy pushed open the door. It was a marvelous place, that antiseptic or rather aseptic kitchen, with its white tiling and enamel, its huge ice-box, and cooking-utensils for every purpose, all of the most expensive and modern make.

There were marks everywhere of a struggle, and by the side of the chef, whose body now lay in the next room awaiting the coroner, lay a long carving-knife with which he had evidently defended himself. On its blade and haft were huge coagulated spots of blood. The body of Sam bore marks of his having been clutched violently by the throat, and in his head was a single, deep wound that penetrated the skull in a most peculiar manner. It did not seem possible that a blow from a knife could have done it. It was a most unusual wound and not at all the sort that could have been made by a bullet.

As Kennedy examined it, he remarked, shaking his head in confirmation of his own opinion, "That must have been done by a Behr bulletless gun."

"A bulletless gun?" I repeated.

"Yes, a sort of pistol with a spring-operated device that projects a sharp blade with great force. No bullet and no powder are used in it. But when it is placed directly over a vital point of the skull so that the aim is unerring, a trigger lets a long knife shoot out with tremendous force, and death is instantaneous."

Near the door, leading to the courtyard that opened on the side street, were some spots of blood. They were so far from the place where the valet had discovered the body of the chef that there could be no doubt that they were blood from the murderer himself. Kennedy's reasoning in the matter seemed irresistible.

He looked under the table near the door, covered with a large light cloth. Beneath the table and behind the cloth he found another blood spot.

"How did that land there?" he mused aloud. "The table-cloth is bloodless."

Craig appeared to think a moment. Then he unlocked and opened the door. A current of air was created and blew the cloth aside.

"Clearly," he exclaimed, "that drop of blood was wafted under the table as the door was opened. The chances are all that it came from a cut on perhaps the hand or face of the murderer himself."

It seemed to be entirely reasonable, for the blood-stains about the room were such as to indicate that he had been badly cut by the carving-knife.

"Whoever attacked the chef must have been deeply wounded," I remarked, picking up the bloody knife and looking about at the stains, comparatively few of which could have come from the one deep fatal wound in the head of the victim.

Kennedy was still engrossed in a study of the stains, evidently considering that their size, shape, and location might throw some light on what had occurred. "Walter," he said finally, "while I'm busy here, I wish you would find that valet, Edward. I want to talk to him."

I found him at last, a clean-cut young fellow of much above average intelligence.

"There are some things I have not yet got clearly, Edward," began Kennedy. "Now where was the body, exactly, when you opened the door?"

Edward pointed out the exact spot, near the side of the kitchen toward the door leading out to the breakfast room and opposite the ice-box.

"And the door to the side street?" asked Kennedy, to all appearances very favorably impressed by the young man.

"It was locked, sir," he answered positively.

Kennedy was quite apparently considering the honesty and faithfulness of the servant. At last he leaned over and asked quickly, "Can I trust you?"

The frank, "Yes," of the young fellow was convincing enough.

"What I want," pursued Kennedy, "is to have some one inside this house who can tell me as much as he can see of the visitors, the messengers that come here this morning. It will be an act of loyalty to your employer, so that you need have no fear about that."

EDWARD bowed, and left us. While I had been seeking him,

Kennedy had telephoned hastily to his laboratory and had found

one of his students there. He had ordered him to bring down an

apparatus which he described and some other material.

While we waited Kennedy sent word to Pitts that he wanted to see him alone for a few minutes.

The instrument appeared to be a rubber bulb and cuff with a rubber bag attached to the inside. From it ran a tube winch ended in another graduated glass tube with a thin line of mercury in it like a thermometer.

Craig adjusted the thing over the brachial artery of Pitts, just above the elbow.

"It may be a little uncomfortable, Mr. Pitts," he apologized, "but it will be for only a few minutes."

Pressure through the rubber bulb shut off the artery so that Kennedy could no longer feel the pulse at the wrist. As he worked, I began to see what he was after. The reading on the graded scale of the height of the column of mercury indicated, I knew, blood pressure. This time, as he worked, I noted also the flabby skin of Pitts as well as the small and sluggish pupils of his eyes.

He completed his test in silence and excused himself, although as we went back to the kitchen I was burning with curiosity.

"What was it?" I asked. "What did you discover?"

"That," he replied, "was a sphygmomanometer, something like the sphygmograph which we used once in another case. Normal blood pressure is 125 millimeters. Mr. Pitts shows a high pressure, very high. The large life insurance companies are now using this instrument. They would tell you that a high pressure like that indicates apoplexy. Mr. Pitts, young as he really is, is actually old. For, you know, the saying is that a man is as old as his arteries. Pitts has hardening of the arteries, arteriosclerosis—perhaps other heart and kidney troubles, in short pre-senility."

Craig paused: then added sententiously as if to himself: "You have heard the latest theories about old age, that it is due to microbic poisons secreted in the intestines and penetrating the intestinal walls? Well, in premature senility the symptoms are the same as in senility, only mental acuteness is not so impaired."

We had now reached the kitchen again. The student had also brought down to Kennedy a number of sterilized microscope slides and test-tubes, and from here and there in the masses of blood spots Kennedy was taking and preserving samples. He also took samples of the various foods, which he preserved in the sterilized tubes.

While he was at work Edward joined us cautiously.

"Has anything happened?" asked Craig.

"A message came by a boy for Mrs. Pitts," whispered the valet.

"What did she do with it?"

"Tore it up."

"And the pieces?"

"She must have hidden them somewhere."

"See if you can get them."

Edward nodded and left us.

"Yes," I remarked after he had gone, "it does seem as if the thing to do was to get on the trail of a person bearing wounds of some kind. I notice, for one thing, Craig, that Edward shows no such marks, nor does anyone else in the house as far as I can see. If it were an 'inside job' I fancy Edward at least could clear himself. The point is to find the person with a bandaged hand or plastered face."

Kennedy assented, but his mind was on another subject. "Before we go we must see Mrs. Pitts alone, if we can," he said simply.

In answer to his inquiry through one of the servants she sent down word that she would see us immediately in her sitting-room. The events of the morning had quite naturally upset her, and she was, if anything, even paler than when we saw her before.

"Mrs. Pitts," began Kennedy, "I suppose you are aware of the physical condition of your husband?"

It seemed a little abrupt to me at first, but he intended it to be. "Why," she asked with real alarm, "is he so very badly?"

"Pretty badly," remarked Kennedy mercilessly, observing the effect of his words. "So badly, I fear, that it would not require much more excitement like to-day's to bring on an attack of apoplexy. I should advise you to take especial care of him, Mrs. Pitts."

Following his eyes, I tried to determine whether the agitation of the woman before us was genuine or not. It certainly looked so. But then, I knew that she had been an actress before her marriage. Was she acting a part now?

"What do you mean?" she asked tremulously.

"Mrs. Pitts," replied Kennedy quickly, observing still the play of emotion on her delicate features, "someone, I believe, either regularly in or employed in this house or who had a ready means of access to it must have entered that kitchen last night. For what purpose, I can leave you to judge. But Sam surprised the intruder there and was killed for his faithfulness."

Her startled look told plainly that though she might have suspected something of the sort she did not think that anyone else suspected, much less actually perhaps knew it.

"I can't imagine who it could be, unless it might be one of the servants," she murmured hastily; adding, "and there is none of them that I have any right to suspect."

She had in a measure regained her composure, and Kennedy felt that it was no use to pursue the conversation further, perhaps expose his hand before he was ready to play it.

"That woman is concealing something," remarked Kennedy to me as we left the house a few minutes later.

"She at least bears no marks of violence herself of any kind," I commented.

"No," agreed Craig, "no, you are right so far." He added: "I shall be very busy in the laboratory this afternoon, and probably longer. However, drop in at dinner-time, and in the meantime, don't say a word to anyone, but just use your position on the Star to keep in touch with anything the police authorities may be doing."

IT was not a difficult commission, since they did nothing but

to issue a statement, the net import of which was to let the

public know that they were very active, although they had nothing

to report.

Kennedy was still busy when I rejoined him, a little late purposely, since I knew that he would be over his head in work.

"What's this—a zoo?" I asked, looking about me as I entered the sanctum that evening.

"What's this—a zoo?" I asked.

There were dogs and guinea-pigs, rats and mice, a menagerie that would have delighted a small boy. It did not look like the same old laboratory for the investigation of criminal science, though I saw on a second glance that it was the same, that there was the usual hurly-burly of microscopes, test-tubes, and all the paraphernalia that were so mystifying at first but in the end under his skilful hand made the most complicated cases seem stupidly simple.

Craig smiled at my surprise. "I'm making a little study of intestinal poisons," he commented, "poisons produced by microbes which we keep under more or less control in healthy life. In death they are the little fellows that extend all over the body and putrefy it. We nourish within ourselves microbes which secrete very virulent poisons, and when those poisons are too much for us—well, we grow old. At least that is the theory of Metchnikoff, who says that old age is an infectious chronic disease. Somehow," he added thoughtfully, "that beautiful white kitchen in the Pitts home had really become a factory for intestinal poisons."

There was an air of suppressed excitement in his manner which told me that Kennedy was on the trail of something unusual.

"Mouth murder," he cried at length, "that was what was being done in that wonderful kitchen. Do you know, the scientific slaying of human beings has far exceeded organized efforts at detection? Of course you expect me to say that; you think I look at such things through colored glasses. But it is a fact, nevertheless.

"It is a very simple matter for the police to apprehend the common murderer whose weapon is a knife or a gun, but it is a different thing when they investigate the death of a person who has been the victim of the modern murderer who slays, let us say, with some kind of deadly bacilli. Authorities say, and I agree with them, that hundreds of murders are committed in this country every year and are not detected because the detectives are not scientists, while the slayers have used the knowledge of the scientists both to commit and to cover up the crimes. I tell you, Walter, a murder science bureau not only would clear up nearly every poison mystery, but also it would inspire such a wholesome fear among would-be murderers that they would abandon many attempts to take life."

He was as excited over the case as I had ever seen him. Indeed it was one that evidently taxed his utmost powers.

"What have you found?" I asked, startled.

"You remember my use of the sphygmomanometer?" he asked. "In the first place that put me on what seems to be a clear trail. The most dreaded of all the ills of the cardiac and vascular systems nowadays seems to be arterio-sclerosis, or hardening of the arteries. It is possible for a man of forty-odd, like Mr. Pitts, to have arteries in a condition which would not be encountered normally in persons under seventy years of age.

"The hard or hardening artery means increased blood pressure, with a consequent increased strain on the heart. This may lead, has led in this case, to a long train of distressing symptoms, and, of course, to ultimate death. Heart disease, according to statistics, is carrying off a greater percentage of persons than formerly. This fact cannot be denied, and it is attributed largely to worry, the abnormal rush of the life of to-day, and sometimes to faulty methods of eating and bad nutrition. On the surface, these natural causes might seem to be at work with Mr. Pitts. But, Walter, I do not believe it, I do not believe it. There is more than that, here. Come, I can do nothing more to-night, until I learn more from these animals and the cultures which I have in these tubes. Let us take a turn or two, then dine, and perhaps we may get some word at our apartment from Edward."

IT was late that night when a gentle tap at the door proved

that Kennedy's hope had not been unfounded. I opened it and let

in Edward, the valet, who produced the fragments of a note, torn

and crumpled.

"There is nothing new, sir," he explained, "except that Mrs. Pitts seems more nervous than ever, and Mr. Pitts, I think, is feeling a little brighter."

Kennedy said nothing, but was hard at work with puckered brows at piecing together the note which Edward had obtained after hunting through the house. It had been thrown into a fireplace in Mrs. Pitts's own room, and only by chance had part of it been unconsumed. The body of the note was gone altogether, but the first part and the last part remained.

Apparently it had been written the very morning on which the murder was discovered.

It read simply, "I have succeeded in having Thornton declared..." Then there was a break. The last words were legible, and were, "...confined in a suitable institution where he can cause no future harm."

There was no signature, as if the sender had perfectly understood that the receiver would understand.

"Not difficult to supply some of the context, at any rate," mused Kennedy. "Whoever Thornton may be, some one has succeeded in having him declared 'insane,' I should supply. If he is in an institution near New York, we must be able to locate him. Edward, this is a very important clue. There is nothing else."

Kennedy employed the remainder of the night in obtaining a list of all the institutions, both public and private, within a considerable radius of the city where the insane might be detained.

THE next morning, after an hour or so spent in the laboratory

apparently in confirming some control tests which Kennedy had

laid out to make sure that he was not going wrong in the line of

inquiry he was pursuing, we started off in a series of flying

visits to the various sanitaria about the city in search of an

inmate named Thornton.

I will not attempt to describe the many curious sights and experiences we saw and had. I could readily believe that anyone who spent even as little time as we did might almost think that the very world was going rapidly insane. There were literally thousands of names in the lists which we examined patiently, going through them all, since Kennedy was not at all sure that Thornton might not be a first name, and we had no time to waste on taking any chances.

It was not until long after dusk that, weary with the search and dust-covered from our hasty scouring of the country in an automobile which Kennedy had hired after exhausting the city institutions, we came to a small private asylum up in Westchester. I had almost been willing to give it up for the day, to start afresh on the morrow, but Kennedy seemed to feel that the case was too urgent to lose even twelve hours over.

It was a peculiar place, isolated, out-of-the-way, and guarded by a high brick wall that enclosed a pretty good sized garden.

A ring at the bell brought a sharp-eyed maid to the door.

"Have you—er—anyone here named Thornton—er—?" Kennedy paused in such a way that if it were the last name he might come to a full stop, and if it were a first name he could go on.

"There is a Mr. Thornton who came yesterday," she snapped ungraciously, "but you cannot see him. It's against the rules."

"Yes—yesterday," repeated Kennedy eagerly, ignoring her tartness. "Could I—" he slipped a crumpled treasury note into her hand—"could I speak to Mr. Thornton's nurse?"

The note seemed to render the acidity of the girl slightly alkaline. She opened the door a little further, and we found ourselves in a plainly furnished reception room, alone.

We might have been in the reception-room of a prosperous country gentleman, so quiet was it. There was none of the raving, as far as I could make out, that I should have expected even in a twentieth century Bedlam, no material for a Poe story of Dr. Tarr and Professor Feather.

At length the hall door opened, and a man entered, not a prepossessing man, it is true, with his large and powerful hands and arms and slightly bowed, almost bulldog legs. Yet he was not of that aggressive kind which would make a show of physical strength without good and sufficient cause.

"You have charge of Mr. Thornton?" inquired Kennedy.

"Yes," was the curt response.

"I trust he is all right here?"

"He wouldn't be here if he was all right," was the quick reply. "And who might you be?"

"I knew him in the old days," replied Craig evasively. "My friend here does not know him, but I was in this part of Westchester visiting and having heard he was here thought I would drop in, just for old time's sake. That is all."

"How did you know he was here?" asked the man suspiciously.

"I heard indirectly from a friend of mine, Mrs. Pitts."

"Oh."

The man seemed to accept the explanation at its face value.

"Is he very—very badly?" asked Craig with well-feigned interest.

"Well," replied the man, a little mollified by a good cigar which I produced, "don't you go a-telling her, but if he says the name Minna once a day it is a thousand times. Them drug-dopes has some strange delusions."

"Strange delusions?" queried Craig. "Why, what do you mean?"

"Say," ejaculated the man. "I don't know you. You come here saying you're friends of Mr. Thornton's. How do I know what you are?"

"Well," ventured Kennedy, "suppose I should also tell you I am a friend of the man who committed him?"

"Of Dr. Thompson Lord?"

"Exactly. My friend here knows Dr. Lord very well, don't you, Walter?"

Thus appealed to I hastened to add, "Indeed I do." Then, improving the opening, I hastened: "Is this Mr. Thornton violent? I think this is one of the most quiet institutions I ever saw for so small a place."

The man shook his head.

"Because," I added, "I thought some drug fiends were violent and had to be restrained by force, often."

"You won't find a mark or a scratch on him, sir," replied the man. "That ain't our system."

"Not a mark or scratch on him," repeated Kennedy thoughtfully. "I wonder if he'd recognize me?"

"Can't say," concluded the man. "What's more, can't try. It's against the rules. Only your knowing so many he knows has got you this far. You'll have to call on a regular day or by appointment to see him, gentlemen."

There was an air of finality about the last statement that made Kennedy rise and move toward the door with a hearty "Thank you, for your kindness," and a wish to be remembered to "poor old Thornton."

AS we climbed into the car he poked me in the ribs. "Just as

good for the present as if we had seen him," he exclaimed.

"Drug-fiend, friend of Mrs. Pitts, committed by Dr. Lord, no

wounds."

Then he lapsed into silence as we sped back to the city.

"The Pitts house," ordered Kennedy as we bowled along, after noting by his watch that it was after nine. Then to me he added, "We must see Mrs. Pitts once more, and alone."

We waited some time after Kennedy sent up word that he would like to see Mrs. Pitts. At last she appeared. I thought she avoided Kennedy's eye, and I am sure that her intuition told her that he had some revelation to make, against which she was steeling herself.

Craig greeted her as reassuringly as he could, but as she sat nervously before us, I could see that she was in reality pale, worn, and anxious.

"We have had a rather hard day," began Kennedy after the usual polite inquiries about her own and her husband's health had been, I thought, a little prolonged by him.

"Indeed?" she asked. "Have you come any closer to the truth?"

Kennedy met her eyes, and she turned away.

"Yes, Mr. Jameson and I have put in the better part of the day in going from one institution for the insane to another."

He paused. The startled look on her face told as plainly as words that his remark had struck home.

Without giving her a chance to reply, or to think of a verbal means of escape, Craig hurried on with an account of what we had done, saying nothing about the original letter which had started us on the search for Thornton, but leaving it to be inferred by her that he knew much more than he cared to tell.

"In short, Mrs. Pitts," he concluded firmly, "I do not need to tell you that I already know much about the matter which you are concealing."

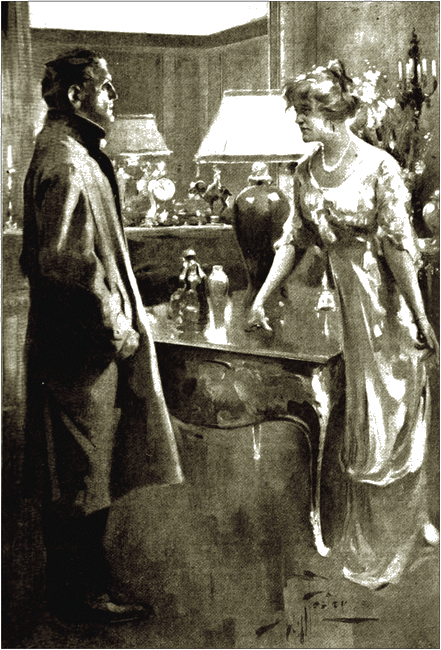

The piling up of fact on fact, mystifying as it was to me who had as yet no inkling of what it was tending toward, proved too much for the woman who knew the truth, yet did not know how much Kennedy knew of it. Minna Pitts was pacing the floor wildly, all the assumed manner of the actress gone from her, yet with the native grace and feeling of the born actress playing unrestrained in her actions.

"You know only part of my story," she cried, fixing him with her now tearless eyes. "It is only a question of time when you will worm it all out by your uncanny, occult methods. Mr. Kennedy, I cast myself on you."

"You know only part of my story," she cried.

The note of appeal in her tone was powerful, but I could not so readily shake off my first suspicions of the woman. Whether or not she convinced Kennedy, he did not show.

"I was only a young girl when I met Mr. Thornton," she raced on. "I was not yet eighteen when we were married. Too late, I found out the curse of his life—and of mine. He was a drug-fiend. From the very first life with him was insupportable. I stood it as long as I could, but when he beat me because he had no money to buy drugs, I left him. I gave myself up to my career on the stage. Later I heard that he was dead—a suicide. I worked, day and night, slaved, and rose in the profession— until, at last, I met Mr. Pitts."

She paused, and it was evident that it was with a struggle that she could talk so.

"Three months after I was married to him, Thornton suddenly reappeared, from the dead it seemed to me. He did not want me back. No, indeed. All he wanted was money. I gave him money, my own money, for I made a great deal in my stage days. But his demands increased. To silence him I have paid him thousands. He squandered them faster than ever. And finally, when it became unbearable, I appealed to a friend. That friend has now succeeded in placing this man quietly in a sanitarium for the insane."

"And the murder of the chef?" shot out Kennedy.

She looked from one to the other of us in alarm. "Before God, I know no more of that than does Mr. Pitts."

Was she telling the truth? Would she stop at anything to avoid the scandal and disgrace of the charge of bigamy? Was there not something still that she was concealing? She took refuge in the last resort —tears.

ENCOURAGING as it was to have made such progress, it did not

seem to me that we were much nearer, after all, to the solution

of the mystery. Kennedy, as usual, had nothing to say until he

was absolutely sure of his ground. He spent the greater part of

the next day hard at work over the minute investigations of his

laboratory, leaving me to arrange the details of a meeting he

planned for that night.

There were present Mr. and Mrs. Pitts, the former in charge of Dr. Lord. The valet Edward was also there, and in a neighboring room was Thornton in charge of two nurses from the sanitarium. Thornton was a sad wreck of a man now, whatever he might have been when his blackmail furnished him with an unlimited supply of his favorite drugs.

"Let us go back to the very start of the case," began Kennedy when we had all assembled, "the murder of the chef, Sam."

It seemed that the mere sound of his voice electrified his little audience. I fancied a shudder passed over the slight form of Mrs. Pitts, as she must have realized that this was the point where Kennedy had left off, in his questioning her the night before.

"There is," he went on slowly, "a blood test so delicate that one might almost say that he could identify a criminal by his very blood-crystals — the finger-prints, so to speak, of his blood. It was by means of these 'hemoglobin clues,' if I may call them so, that I was able to get on the right trail. For the fact is that a man's blood is not like that of any other living creature. Blood of different men, of men and women differ. I believe that in time we shall be able to refine this test to tell the exact individual, too.

"What is this principle? It is that the hemoglobin or red coloring-matter of the blood forms crystals. That has long been known, but working on this fact Dr. Reichert and Professor Brown of the University of Pennsylvania have made some wonderful discoveries.

"We could distinguish human from animal blood before, it is true. But the discovery of these two scientists takes us much further. By means of blood-crystals we can distinguish the blood of man from that of the animals and in addition that of white men from that of negroes and other races. It is often the only way of differentiating between various kinds of blood.

"The variations in crystals in the blood are in part of form and in part of molecular structure, the latter being discovered only by means of the polarizing microscope. A blood-crystal is only one two-thousand-two-hundred-and-fiftieth of an inch in length and one nine-thousandth of an inch in breadth. And yet, minute as these crystals are, this discovery is of immense medico-legal importance. Crime may now be traced by blood-crystals."

He displayed on his table a number of enlarged micro-photographs. Some were labeled, "Characteristic crystals of white man's blood;" others "Crystallization of negro blood"; still others, "Blood-crystals of the cat."

"I have here," he resumed, after we had all examined the photographs and had seen that there was indeed a vast amount of difference, "three characteristic kinds of crystals, all of which I found in the various spots in the kitchen of Mr. Pitts. There were three kinds of blood, by the infallible Reichert test."

I had been prepared for his discovery of two kinds, but three heightened the mystery still more.

"There was only a very little of the blood which was that of the poor, faithful, unfortunate Sam, the negro chef," Kennedy went on. "A little more, found far from his body, is that of a white person. But most of it is not human blood at all. It was the blood of a cat."

The revelation was startling. Before any of us could ask, he hastened to explain.

"It was placed there by some one who wished to exaggerate the struggle in order to divert suspicion. That person had indeed been wounded slightly, but wished it to appear that the wounds were very serious. The fact of the matter is that the carving-knife is spotted deeply with blood, but it is not human blood. It is the blood of a cat. A few years ago even a scientific detective would have concluded that a fierce hand-to-hand struggle had been waged and that the murderer was, perhaps, fatally wounded. Now, another conclusion stands proved infallibly by this Reichert test. The murderer was wounded, but not badly. That person even went out of the room and returned later, probably with a can of animal blood, sprinkled it about to give the appearance of a struggle, perhaps thought of preparing in this way a plea of self-defense. If that latter was the case, this Reichert test completely destroys it, clever though it was."

No one spoke, but the same thought was openly in all our minds. Who was this wounded criminal?

I asked myself the usual query of the lawyers and the detectives— Who would benefit most by the death of Pitts? There was but one answer, apparently, to that. It was Minna Pitts. Yet it was difficult for me to believe that a woman of her ordinary gentleness could be here to-night, faced even by so great exposure, yet be so solicitous for him as she had been and then at the same time be plotting against him. I gave it up, determining to let Kennedy unravel it in his own way.

Craig evidently had the same thought in his mind, however, for he continued: "Was it a woman who killed the chef? No, for the third specimen of blood, that of the white person, was the blood of a man; not of a woman."

Pitts had been following closely, his unnatural eyes now gleaming. "You said he was wounded, you remember," he interrupted, as if casting about in his mind to recall some one who bore a recent wound. "Perhaps it was not a bad wound, but it was a wound, nevertheless, and some one must have seen it, must know about it. It is not three days."

Kennedy shook his head. It was a point that had bothered me a great deal.

"As to the wounds," he added in a measured tone, "although this occurred scarcely three days ago, there is no person even remotely suspected of the crime who can be said to bear on his hands or face others than old scars of wounds."

He paused. Then he shot out in quick staccato, "Did you ever hear of Dr. Carrel's most recent discovery of accelerating the healing of wounds so that those which under ordinary circumstances might take ten days to heal might be healed in twenty-four hours?"

Rapidly, now, he sketched the theory. "If the factors that bring about the multiplication of cells and the growth of tissues were discovered, Dr. Carrel said to himself, it would perhaps become possible to hasten artificially the process of repair of the body. Aseptic wounds could probably be made to cicatrize more rapidly. If the rate of reparation of tissue were hastened only ten times, a skin wound would heal in less than twenty-four hours and a fracture of the leg in four or five days.

"For five years Dr. Carrel has been studying the subject, applying various extracts to wounded tissues. All of them increased the growth of connective tissue, but the degree of acceleration varied greatly. In some cases it was as high as forty times the normal. Dr. Carrel's dream of ten times the normal was exceeded by himself."

ASTOUNDED as we were by this revelation, Kennedy did not seem

to consider it as important as one that he was now hastening to

show us. He took a few cubic centimeters of some culture which he

had been preparing, placed it in a tube, and poured in eight or

ten drops of sulphuric acid. He shook it.

"I have here a culture from some of the food that I found was being or had been prepared for Mr. Pitts. It was in the icebox."

Then he took another tube. "This," he remarked, "is a one-to-one-thousand solution of sodium nitrite."

He held it up carefully and poured three or four cubic centimeters of it into the first tube so that it ran carefully down the side in a manner such as to form a sharp line of contact between the heavier culture with the acid and the lighter nitrite solution.

"You see," he said, "the reaction is very clear cut if you do it this way. The ordinary method in the laboratory and the textbooks is crude and uncertain."

"What is it?" asked Pitts eagerly, leaning forward with unwonted strength and noting the pink color that appeared at the junction of the two liquids, contrasting sharply with the portions above and below.

"The ring or contact test for indol," Kennedy replied, with evident satisfaction. "When the acid and the nitrites are mixed the color reaction is unsatisfactory. The natural yellow tint masks that pink tint, or sometimes causes it to disappear, if the tube is shaken. But this is simple, clear, delicate—unescapable. There was indol in that food of yours, Mr. Pitts."

"Indol?" repeated Pitts.

"Is," explained Kennedy, "a chemical compound—one of the toxins secreted by intestinal bacteria and responsible for many of the symptoms of senility. It used to be thought that large doses of indol might be consumed with little or no effect on normal man, but now we know that headache, insomnia, confusion, irritability, decreased activity of the cells, and intoxication are possible from it. Comparatively small doses over a long time produce changes in organs that lead to serious results.

"It is," went on Kennedy, as the full horror of the thing sank into our minds, "the indol- and phenol-producing bacteria which are the undesirable citizens of the body, while the lactic-acid producing germs check the production of indol and phenol. In my tests here to-day, I injected four one-hundredths of a grain of indol into a guinea-pig. The animal had sclerosis or hardening of the aorta. The liver, kidneys, and supra-renals were affected, and there was a hardening of the brain. In short, there were all the symptoms of old age."

We sat aghast. Indol! What black magic was this? Who put it in the food?

"It is present," continued Craig, "in much larger quantities than all the Metchnikoff germs could neutralize. What the chef was ordered to put into the food to benefit you, Mr. Pitts, was rendered valueless, and a deadly poison was added by what another—"

Minna Pitts had been clutching for support at the arms of her chair as Kennedy proceeded. She now threw herself at the feet of Emery Pitts.

"Forgive me," she sobbed. "I can stand it no longer. I had tried to keep this thing about Thornton from you. I have tried to make you happy and well—oh—tried so hard, so faithfully. Yet that old skeleton of my past which I thought was buried would not stay buried. I have bought Thornton off again and again, with money— my money—only to find him threatening again. But about this other thing, this poison, I am as innocent, and I believe Thornton is as—"

Craig laid a gentle hand on her lips. She rose wildly and faced him in passionate appeal.

"Who—who is this Thornton?" demanded Emery Pitts.

Quickly, delicately, sparing her as much as he could, Craig hurried over our experiences.

"He is in the next room," Craig went on, then facing Pitts added: "With you alive, Emery Pitts, this blackmail of your wife might have gone on, although there was always the danger that you might hear of it—and do as I see you have already done— forgive, and plan to right the unfortunate mistake. But with you dead, this Thornton, or rather some one using him, might take away from Minna Pitts her whole interest in your estate, at a word. The law, or your heirs at law, would never forgive as you would."

Pitts, long poisoned by the subtle microbic poison, stared at Kennedy as if dazed.

"Who was caught in your kitchen, Mr. Pitts, and, to escape detection, killed your faithful chef and covered his own traces so cleverly?" rapped out. Kennedy. "Who would have known the new process of healing wounds? Who knew about the fatal properties of indol? Who was willing to forego a one-hundred-thousand-dollar prize in order to gain a fortune of many hundreds of thousands?"

Kennedy paused, then finished with irresistibly dramatic logic,

"Who else but the man who held the secret of Minna Pitts's past and power over her future so long as he could keep alive the unfortunate Thornton—the up-to-date doctor who substituted an elixir of death at night for the elixir of life prescribed for you by him in the daytime—Dr. Lord."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.