RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Hearst's Magazine, February 1913, with "The Vampire"

A MIDDLE-AGED man and a young girl, heavily veiled, were waiting for Kennedy one afternoon when we came in from a brisk walk in the cutting river wind on the Drive.

"Winslow is my name, sir," the man began, rising nervously as we entered the room, "and this is my only daughter, Ruth."

Kennedy bowed and we waited for the man to proceed. He drew his hand over his forehead which was moist with perspiration in spite of the season. Ruth Winslow was an attractive young woman, I could see at a glance, although her face was almost completely hidden by the thick veil.

"Perhaps, Ruth, I had better—ah—see these gentlemen alone?" suggested her father gently.

"No, father," she answered in a tone of forced bravery, "I think not. I can stand it. I must stand it. Perhaps I can help you in telling about the—the case."

"No, father," she answered in a tone of forced bravery.

Mr. Winslow cleared his throat.

"We are from Goodyear, a little mill-town," he proceeded slowly, "and as you doubtless can see we have just arrived after traveling all day."

"Goodyear," repeated Kennedy slowly as the man paused. "The chief industry, of course, is rubber, I suppose."

"Yes," assented Mr. Winslow, "the town centers about rubber. Our factories are not the largest but are very large, nevertheless, and are all that keep the town going. It is on rubber, also, I fear, that the tragedy which I am about to relate hangs. I suppose the New York papers have had nothing to say of the strange death of Bradley Cushing, a young chemist in Goodyear who was formerly employed by the mills but had lately set up a little laboratory of his own?"

Kennedy turned to me. "Nothing unless the late editions of the evening papers have it," I replied.

"Perhaps it is just as well," continued Mr. Winslow. "They wouldn't have it straight. In fact no one has it straight yet. That is why we have come to you. You see, to my way of thinking Bradley Cushing was on the road to changing the name of the town from Goodyear to Cushing. He was not the inventor of synthetic rubber about which you hear nowadays, but he had improved the process so much that there is no doubt that synthetic rubber would soon have been on the market cheaper and better than the best natural rubber from Para.

"Goodyear is not a large place but it is famous for its rubber and uses a great deal of raw material. We have sent out some of the best men in the business, seeking new sources in South America, in Mexico, in Ceylon, Malaysia and the Congo. What our people do not know about rubber is hardly worth knowing, from the crude gum to the thousands of forms of finished products. Goodyear is a wealthy little town, too, for its size. Naturally all its investments are in rubber, not only in our own mills but in companies all over the world. Last year several of our leading citizens became interested in a new concession in the Congo granted to a group of American capitalists, among whom was Lewis Borland, who is easily the local magnate of our town. When this group organized an expedition to explore the region preparatory to taking up the concession several of the best known people in Goodyear accompanied the party and later subscribed for large blocks of stock.

"I say all this so that you will understand at the start just what part rubber plays in the life of our little community. You can readily see that such being the case, whatever advantage the world at large might gain from cheap synthetic rubber would scarcely benefit those whose money and labor had been expended on the assumption that rubber would be scarce and dear. Naturally, then, Bradley Cushing was not precisely popular with a certain set in Goodyear. As for myself I am frank to admit that I might have shared the opinion of many others regarding him, for I have a small investment in this Congo enterprise myself. But the fact is that Cushing, when he came to our town fresh from his college fellowship in industrial chemistry, met my daughter."

Without taking his eyes off Kennedy he reached over and patted the gloved hand that clutched the arm of the chair alongside his own. "They were engaged and often they used to talk over what they would do when Bradley's invention of a new way to polymerize isoprene, as the process is called, had solved the rubber question and had made him rich. I firmly believe that their dreams were not day dreams, either. The thing was done. I have seen his products and I know something about rubber. There were no impurities in his rubber."

Mr. Winslow paused. Ruth was sobbing quietly.

"This morning," he resumed hastily, "Bradley Cushing was found dead in his laboratory under the most peculiar circumstances. I do not know whether his secret died with him or whether someone has stolen it. I did not wait to make an investigation myself. From the indications I concluded that he had been murdered."

Such was the case as Kennedy and I heard it then.

Ruth looked up at him with tearful eyes wistful with pain, "Would Mr. Kennedy work on it?" There was only one answer.

AS we sped out to the little mill-town on the last train,

after Kennedy had insisted on taking us all to a quiet little

restaurant, he placed us so that Miss Winslow was furthest from

him and her father nearest. I could hear now and then scraps of

their conversation as he resumed his questioning and knew that Mr. Winslow was proving to be a good observer.

"Cushing used to hire a young fellow of some scientific experience, named Strong," said Mr. Winslow as he endeavored to piece the facts together as logically as it was possible to do. "Strong used to open his laboratory for him in the morning, clean up the dirty apparatus, and often assist him in some of his experiments. This morning when Strong approached the laboratory at the usual time he was surprised to see that though it was broad daylight there was a light burning. He was alarmed and before going in looked through the window. The sight that he saw froze him. There lay Cushing on a workbench and beside him and around him pools of coagulating blood. The door was not locked, as we found afterward, but the young man did not stop to enter. He ran to me and fortunately I met him at our door. I went back.

"We opened the unlocked door. The first thing, as I recall it, that greeted me was an unmistakable odor of oranges. It was a very penetrating and very peculiar odor. I didn't understand it, for there seemed to be something else in it besides the orange smell. However, I soon found out what it was, or at least Strong did. I don't know whether you know anything about it, but it seems that when you melt real rubber in the effort to reduce it to carbon and hydrogen you get a liquid substance which is known as isoprene. Well, isoprene, according to Strong, gives out an odor something like ether. Cushing or someone else had apparently been heating isoprene. As soon as Strong mentioned the smell of ether I recognized that that was what made the smell of oranges so peculiar.

"However, that's not the point. There lay Cushing on his back on the workbench, just as Strong had said. I bent over him and in his arm which was bare I saw a little gash made by some sharp instrument and laying bare an artery, I think, which was cut. Long spurts of blood covered the floor for some distance around and from the veins in his arm, which had also been severed, a long stream of blood led to a hollow in the cement floor where it had collected. I believe that he bled to death."

"And the motive for such a terrible crime?" queried Craig.

Mr. Winslow shook his head helplessly. "I suppose there are plenty of motives," he answered slowly, "as many motives as there are big investments in rubber-producing ventures in Goodyear."

"But have you any idea who would go so far to protect his investments as to kill?" persisted Kennedy.

Mr. Winslow made no reply. "Who," asked Kennedy, "was chiefly interested in the rubber works where Cushing was formerly employed?"

"The president of the company is the Mr. Borland whom I mentioned," replied Mr. Winslow. "He is a man of about forty, I should say, and is reputed to own a majority of the—"

"Oh, father," interrupted Miss Winslow who had caught the drift of the conversation in spite of the pains that had been taken to keep it away from her, "Mr. Borland would never dream of such a thing. It is wrong even to think of it."

"I didn't say that he would, my dear," corrected Mr. Winslow gently. "Professor Kennedy asked me who was chiefly interested in the rubber works and Mr. Borland owns a majority of the stock." He leaned over and whispered to Kennedy, "Borland is a visitor at our home, and between you and me, he thinks a great deal of Ruth."

I looked quickly at Kennedy, but he was absorbed in looking out of the car window at the landscape which he did not and could not see.

"You said there were others who had an interest in outside companies," cross-questioned Kennedy. "I take it that you mean companies dealing in crude rubber, the raw material, people with investments in plantations and concessions, perhaps. Who are they? Who were the men who went on that expedition to the Congo with Borland which you mentioned?"

"Of course, there was Borland himself," answered Winslow. "Then there was a young chemist named Lathrop, a very clever and ambitious fellow who succeeded Cushing when he resigned from the works, and Dr. Harris, who was persuaded to go because of his friendship for Borland. After they took up the concession I believe all of them put money into it, though how much I can't say."

I was curious to ask whether there were any other visitors at the Winslow house who might be rivals for Ruth's affections, but there was no opportunity.

NOTHING more was said until we arrived at Goodyear.

We found the body of Cushing lying in a modest little mortuary chapel of an undertaking establishment on the main street. Kennedy at once began his investigation by discovering what seemed to have escaped others. About the throat were light discolorations that showed that the young inventor had been choked by a man with a powerful grasp, although the fact that the marks had escaped observation led quite obviously to the conclusion that he had not met his death in that way, and that the marks probably played only a minor part in the tragedy.

Kennedy passed over the doubtful evidence of strangulation for the more profitable examination of the little gash in the wrist.

"The radial artery has been cut," he mused.

A low exclamation from him brought us all bending over him as he stooped and examined the cold form. He was holding in the palm of his hand a little piece of something that shone like silver. It was in the form of a minute hollow cylinder with two grooves on it, a cylinder so tiny that it would scarcely have slipped over the point of a pencil.

"Where did you find it?" I asked eagerly.

He pointed to the wound. "Sticking in the severed end of a piece of vein," he replied, half to himself, "cuffed over the end of the radial artery which had been severed, and done so neatly as to be practically hidden. It was done so cleverly that the inner linings of the vein and artery, the endothelium as it is called, were in complete contact with each other."

As I looked at the little silver thing and at Kennedy's face which betrayed nothing I felt that here indeed was a mystery. What new scientific engine of death was that little hollow cylinder?

"Next I should like to visit the laboratory," he remarked simply.

FORTUNATELY the laboratory had been shut and nothing had been

disturbed except by the undertaker and his men who had carried

the body away. Strong had left word that he had gone to Boston

where in a safe deposit box was a sealed envelope in which

Cushing kept a copy of the combination of his safe, which had

died with him. There was, therefore, no hope of seeing the

assistant until the morning.

Kennedy found plenty to occupy his time in his minute investigation of the laboratory. There, for instance, was the pool of blood leading back by a thin dark stream to the workbench and its terrible figure which I could almost picture to myself lying there through the silent hours of the night before, with its life blood slowly oozing away, unconscious, powerless to save itself. There were spurts of arterial blood on the floor and on the nearby laboratory furniture, and beside the workbench another smaller and isolated pool of blood.

On a table in a corner by the window stood a microscope which Cushing evidently used and near it a box of fresh sterilized slides. Kennedy, who had been casting his eye carefully about taking in the whole laboratory, seemed delighted to find the slides. He opened the box and gingerly took out some of the little oblong pieces of glass, on each of which he dropped a couple of minute drops of blood from the arterial spurts and the venous pools on the floor.

Near the workbench were circular marks, much as if some jars had been set down there. We were watching him, almost in awe at the matter of fact manner in which he was proceeding in what to us was nothing but a hopeless enigma, when I saw him stoop and pick up a few little broken pieces of glass. There seemed to be blood spots on the glass, as on other things, but particularly interesting lo him.

A moment later I saw that he was holding in his hand what were apparently the remains of a little broken vial which he had fitted together from the pieces. Evidently it had been used and dropped in haste.

"A vial for a local anesthetic," he remarked. "This is the sort of thing that might be injected into an arm or leg and deaden the pain of a cut, but that is all. It wouldn't affect the consciousness or prevent anyone from resisting a murderer to the last. I doubt if that had anything directly to do with his death, or perhaps even that this is Cushing's blood on it."

Unlike Winslow I had seen Kennedy in action so many times that I knew it was useless to speculate. But I was fascinated, for the deeper we got into the case, the more unusual and inexplicable it seemed. I gave that end of it up, but the fact that Strong had gone to secure the combination of the safe suggested to me to examine that article. There was certainly no evidence of robbery or even of an attempt at robbery there.

"Was any doctor called?" asked Kennedy.

"Yes," he replied. "Though I knew it was of no use I called in Dr. Howe who lives up the street from the laboratory. I should have called Dr. Harris who used to be my own physician, but since his return from Africa with the Borland expedition he has not been in very good health and has practically given up his practice. Dr. Howe is the best practicing physician in town, I think."

"We shall call on him to-morrow," said Craig snapping his watch which already marked far after midnight.

DR. HOWE proved, the next day, to be an athletic-looking man

and I could not help noticing and admiring his powerful frame and

his hearty handshake as he greeted us when we dropped into his

office with a card from Winslow.

The doctor's theory was that Cushing had committed suicide.

"But why should a young man who had invented a new method of polymerizing isoprene, who was going to become wealthy, and was engaged to a beautiful young girl commit suicide?"

The doctor shrugged his shoulders. It was evident that he, too, belonged to the "natural rubber set" which dominated Goodyear.

"I haven't looked into the case very deeply, but I'm not so sure that he had the secret, are you?"

Kennedy smiled. "That is what I'd like to know. I suppose that an expert like Mr. Borland could tell me, perhaps?"

"I should think so."

"Where is his office?" asked Craig. "Could you point it out to me from the window?"

Kennedy was standing by one of the windows of the doctor's office and as he spoke he turned and drew a little field glass from his pocket. "Which end of the rubber works is it?"

Dr. Howe tried to direct him but Kennedy appeared unwarrantably obtuse, requiring the doctor to raise the window, and it was some moments before he got his glasses on the right spot.

Kennedy and I thanked the doctor for his courtesy and left the office.

WE went at once to the office of Dr. Harris, to whom Winslow

had also given us cards. We found him an anemic man, half asleep.

Kennedy tentatively suggested the murder of Cushing.

"Well, if you ask me my opinion," snapped out the doctor, "although I wasn't called into the case, from what I hear, I'd say that he was murdered."

"Some seem to think it was suicide," prompted Kennedy.

"People who have brilliant prospects and are engaged to pretty girls don't usually die of their own accord," rasped Harris.

"So you think he really did have the secret of artificial rubber?" asked Craig.

"Not artificial rubber. Synthetic rubber. It was the real thing, I believe."

"Did Mr. Borland and his new chemist Lathrop believe it, too?"

"I can't say. But I should surely advise you to see them." The doctor's face was twitching nervously.

"Where is Borland's office?" repeated Kennedy, again taking from his pocket the field glass and adjusting it carefully by the window.

"Over there," directed Harris, indicating the corner of the works to which we had already been directed.

Kennedy had stepped closer to the window before him and I stood beside him looking out also.

"The cut was a very peculiar one," remarked Kennedy still adjusting the glasses. "An artery and a vein had been placed together so that the endothelium or inner lining of each was in contact with the other giving a continuous serous surface. Which window did you say was Borland's? I wish you'd step to the other window and raise it, so that I can be sure. I don't want to go wandering all over the works looking for him."

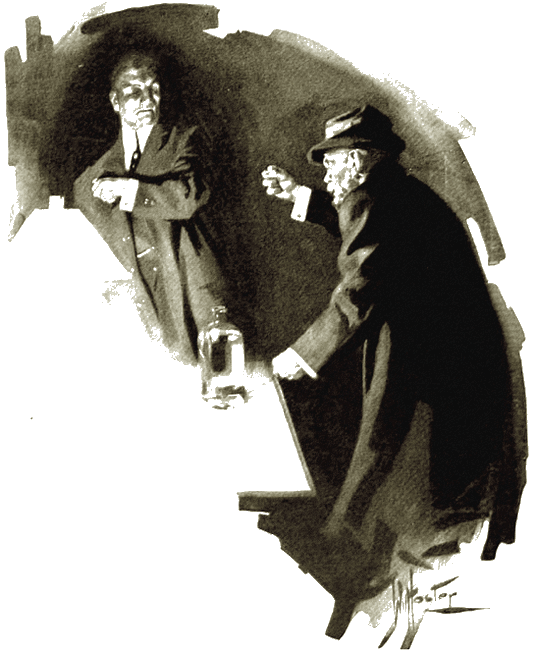

"The cut was a very peculiar one," remarked Kennedy.

"Yes," the doctor said as we went leaving him standing beside the window from which he had been directing us, "yes, you surely should see Mr. Borland. And don't forget that young chemist of his, Lathrop, either. If I can be of any more help to you, come back again."

IT was a long walk through the village and factory yards to

the office of Lewis Borland, but we were amply repaid by finding

him in and ready to see us. Borland was a typical Yankee, tall,

thin, evidently predisposed to indigestion, a man of tremendous

mental and nervous energy and with a hidden wiry strength.

"Mr. Borland," introduced Kennedy, changing his tactics and adopting a new role, "I've come down to you as an authority on rubber to ask you what your opinion is regarding the invention of a townsman of yours named Cushing."

"Cushing?" repeated Borland in some surprise. "Why—"

"Yes," interrupted Kennedy, "I understand all about it. I had heard of his invention in New York and would have put some money into it if I could have been convinced. I was to see him to-day, but of course, as you were going to say, his death prevents it. Still I should like to know what you think about it."

"Well," Borland added, jerking out his words nervously as seemed to be his habit, "Cushing was a bright young fellow. He used to work for me until he began to know too much about the rubber business."

"Do you know anything about his scheme?" insinuated Kennedy.

"Very little, except that it was not patented yet, I believe, though he told everyone that the patent was applied for and he expected to get a basic patent in some way without any interference."

"Well," drawled Kennedy, affecting as nearly as possible the air of a promoter, "if I could get his assistant, or someone who had authority to be present, would you, as a practical rubber man, go over to his laboratory with me? I'd join you in making an offer to his estate for the rights to the process, if it seemed any good."

"You're a cool one," ejaculated Borland with a peculiar avaricious twinkle in the corners of his eyes. "His body is scarcely cold and yet you come around proposing to buy out his invention and—and, of all persons, you come to me."

"To you?" inquired Kennedy blandly.

"Yes, to me. Don't you know that synthetic rubber would ruin the business system that I have built up here?"

Still Craig persisted and argued.

"Young man," said Borland rising at length as if an idea had struck him, "I like your nerve. Yes, I will go. I'll show you that I don't fear any competition from rubber made out of fusel oil or any other old kind of oil." He rang a bell and a boy answered. "Call Lathrop," he ordered.

THE young chemist Lathrop proved to be a bright and active man

of the new school, though a good deal of a rubber stamp. Whenever

it was compatible with science and art he readily assented to

every proposition that his employer laid down.

Kennedy had already telephoned to the Winslows and Miss Win slow had answered that Strong had returned from Boston. After a little parleying the second visit to the laboratory was arranged and Miss Winslow was allowed to be present with her father, after Kennedy had been assured by Strong that the gruesome relics of the tragedy would be cleared away.

It was in the forenoon that we arrived with Borland and Lathrop. I could not help noticing the cordial manner with which Borland greeted Miss Winslow. There was something obtrusive even in his sympathy. Strong, whom we met now for the first time, seemed rather suspicious of the presence of Borland and his chemist, but made an effort to talk freely without telling too much.

"Of course you know," commenced Strong after proper urging, "that it has long been the desire of chemists to synthesize rubber by a method that will make possible its cheap production on a large scale. In a general way I know what Mr. Cushing had done, but there are parts of the process which are covered in the patents applied for of which I am not at liberty to speak yet."

"Where are the papers in the case, the documents showing the application for the patent, for instance?" asked Kennedy.

"In the safe, sir," replied Strong.

Strong set to work on the combination which he had obtained from the safe deposit vault. I could see that Borland and Miss Winslow were talking in a low tone.

"Are you sure that it is a fact?" I overheard him ask, though I had no idea what they were talking about.

"As sure as I am that the Borland Rubber Works are a fact," she replied.

Craig also seemed to have overheard for he turned quickly. Borland had taken out his penknife and was wetting the blade carefully preparing to cut into a piece of the synthetic rubber. In spite of his expressed scepticism I could see that he was eager to learn what the product was really like.

Strong meanwhile had opened the safe and was going over the papers. A low exclamation from him brought us around the little pile of documents. He was holding a will in which nearly everything belonging to Cushing was left to Miss Winslow.

Not a word was said although I noticed that Kennedy moved quickly to her side, fearing that the shock of the discovery might have a bad effect on her, but she took it with remarkable calmness. It was apparent that Cushing had taken the step of his own accord and had said nothing to her about it.

"What does anything amount to?" she said tremulously at last. "The dream is dead without him in it."

"Come," urged Kennedy gently. "This is enough for today."

AN hour later we were speeding back to New York. Kennedy had

no apparatus to work with out at Goodyear and could not improvise

it. Winslow agreed to keep us in touch with any new developments

during the few hours that Craig felt it was necessary to leave

the scene of action.

Back again in New York, Craig took a cab directly for his laboratory, leaving me marooned with instructions not to bother him for several hours. I employed the time in a little sleuthing on my own account, endeavoring to look up the records of those involved in the case. I did not discover much except an interview that had been given at the time of the return of his expedition by Borland to the Star in which he gave a graphic description of the dangers from disease that they had encountered.

I mention it because though it did not impress me much when I read it, it at once leaped into my mind when the interminable hours were over and I rejoined Kennedy. He was bending over a new microscope.

"This is a rubber age, Walter," he began, "and the stories of men who have been interested in rubber often sound like fiction."

He slipped a slide under the microscope, looked at it and then motioned to me to do the same. "Here is a very peculiar culture which I have found in some of that blood," he commented. "The germs are much larger than bacteria and they can be seen with a comparatively low power microscope swiftly darting between the blood cells, brushing them aside, but not penetrating them as some parasites, like that of malaria, do, and spectroscope tests show the presence of a rather well-known chemical in that blood."

"A poisoning, then?" I ventured. "Perhaps he suffered from the disease that many rubber workers get from the bisulphide of carbon. He must have done a good deal of vulcanizing of his own rubber, you know."

"No," smiled Craig enigmatically, "it wasn't that. It was an arsenic derivative. Here's another thing. You remember the field glass I used?"

He had picked it up from the table and was pointing at a little hole in the side, that had escaped my notice before. "This is what you might call a right-angled camera. I point the glass out of the window and while you think I am looking through it I am really focusing it on you and taking your picture standing there beside me and out of my apparent line of vision. It would deceive the most wary."

JUST then a long distance call from Winslow told us that

Borland had been to call on Miss Ruth and in as kindly a way as

could be had offered her half a million dollars for her rights in

the new patent. At once it flashed over me that he was trying to

get control of and suppress the invention in the interests of his

own company, a thing that has been done hundreds of times. Or

could it all have been part of a conspiracy? And if it was his

conspiracy, would he succeed in tempting his friend, Miss

Winslow, to fall in with this glittering offer?

Kennedy evidently thought, also, that the time for action had come, for without a word he set to work packing his apparatus and we were again headed for Goodyear.

WE arrived late at night, or rather in the morning, but in

spite of the late hour Kennedy was up early urging me to help him

carry the stuff over to Cushing's laboratory. By the middle of

the morning he was ready and had me scouring about town

collecting his audience which consisted of the Winslows, Borland

and Lathrop, Dr. Howe, Dr. Harris, Strong and myself. The

laboratory was darkened and Kennedy took his place beside an

electric moving picture apparatus.

The first picture was different from anything any of us had ever seen on a screen before. It seemed to be a mass of little dancing globules. "This," explained Kennedy, "is what you would call an educational moving picture, I suppose. It shows normal blood corpuscles as they are in motion in the blood of a healthy man. Those little round cells are the red corpuscles and the larger irregular cells are the white corpuscles."

He stopped the film. The next picture was a sort of enlarged and elongated house fly, apparently, of sombre grey color, with a narrow body, thick proboscis and wings that overlapped like the blades of a pair of shears.

"This," he went on, "is a picture of the now well-known tse-tse fly found over a large area of Africa. It has a bite something like a horse-fly and is a perfect bloodsucker. Vast territories of thickly populated fertile country near the shores of lakes and rivers are now depopulated as a result of the death-dealing bite of these flies, more deadly than the blood-sucking, vampirish ghosts with which in the middle ages people supposed night air to be inhabited. For this fly carries with it germs which it leaves in the blood of its victims, which I shall show next."

A new film started.

"Here is a picture of some blood so infected. Notice that worm-like sheath of undulating membrane terminating in a slender whip-like process by which it moves about. That thing wriggling about like a minute electric eel, always in motion, is known as the trypanosome.

"Isn't this a marvellous picture? To see the micro-organism move, evolve and revolve in the midst of normal cells, uncoil and undulate in the fluids which they inhabit, to see them play hide and seek with the blood corpuscles and clumps of fibrin, turn, twist, and rotate as if in a cage, to see these deadly little trypanosomes moving back and forth in every direction displaying their delicate undulating membranes and shoving aside the blood cells that are in their way while by their side the leucocytes or white corpuscles lazily extend or retract their pseudopods of protoplasm, to see all this as it is shown before us here is to realize that we are in the presence of an unknown world, a world infinitesimally small, but as real and as complex as that about us. With the cinematograph and the ultra-microscope we can see what no other forms of photography can reproduce.

"I have secured these pictures so that I can better mass up the evidence against a certain person in this room. For in the blood of one of you is now going on the fight which you have here seen portrayed by the picture machine. Notice how the blood corpuscles in this infected blood have lost their smooth, glossy appearance, become granular and incapable of nourishing the tissues. The trypanosomes are fighting with the normal blood cells. Here we have the lowest group of animal life, the protozoa, at work killing the highest, man."

Kennedy needed nothing more than the breathless stillness to convince him of the effectiveness of his method of presenting his case.

"Now," he resumed, "let us leave this blood-sucking, vampirish tse-tse fly for the moment. I have another revelation to make."

He laid down on the table under the lights, which now flashed up again, the little hollow silver cylinder.

"This little instrument," Kennedy explained, "which I have here is known as a canula, a little canal, for leading off blood from the veins of one person to another—in other words blood transfusion. Modern doctors are proving themselves quite successful in its use.

"Of course, like everything, it has its own peculiar dangers. But the one point I wish to make is this: In the selection of a donor for transfusion people fall in to definite groups. Tests of blood must be made first to see whether it 'agglutinates,' and in this respect there are four classes of persons. In our case this matter had to be neglected. For, gentlemen, there were two kinds of blood on that laboratory floor, and they do not agglutinate. This, in short, was what actually happened. An attempt was made to transfuse Cushing's blood as donor to another person as recipient. A man suffering from the disease caught from the bite of the tse-tse fly—the deadly sleeping sickness so well known in Africa—has deliberately tried a form of robbery which I believe to be without parallel. He has stolen the blood of another!

"He stole it in a desperate attempt to stay an incurable disease. This man had used an arsenic compound called atoxyl, till his blood was filled with it and its effects on the trypanosomes nil. There was but one wild experiment more to try—the stolen blood of another." Craig paused to let the horror of the crime sink into our minds.

"Someone in the party which went to look over the concession in the Congo contracted the sleeping sickness from the bites of those blood-sucking flies. That person has now reached the stage of insanity, and his blood is full of the germs and overloaded with atoxyl.

"Everything had been tried and had failed. He was doomed. He saw his fortune menaced by the discovery of the way to make synthetic rubber. Life and money were at stake. One night, nerved up by a fit of insane fury, with a power far beyond what one would expect in his ordinary weakened condition, he saw a light in Cushing's laboratory. He stole in stealthily. He seized the inventor with his momentarily superhuman strength and choked him. As they struggled he must have shoved a sponge soaked with ether and orange essence under his nose. Cushing went under.

"Resistance overcome by the anesthetic, he dragged the now insensible form to the work bench. Frantically he must have worked. He made an incision and exposed the radial artery, the pulse. Then he must have administered a local anesthetic to himself in his arm or leg. He secured a vein and pushed the cut end over this little canula. Then he fitted the artery of Cushing over that and the blood that was, perhaps, to save his life began flowing into his depleted veins.

"Who was this madman? I have watched the actions of those whom I suspected when they did not know they were being watched. I did it by using this neat little device which looks like a field glass but is really a camera that takes pictures of things at right angles to the direction in which the glass seems to be pointed. One person, I found, had a wound on his leg the wrapping of which he adjusted nervously when he thought no one was looking. He had difficulty in limping even a short distance to open a window."

Kennedy uncorked a bottle and the subtle odor of oranges mingled with ether stole through the room.

"Someone here will recognize that odor immediately. It is the new orange-essence vapor anesthetic, a mixture of essence of orange with ether and chloroform. The odor hidden by the orange which lingered in the laboratory, Mr. Winslow and Mr. Strong, was not isoprene, but really ether.

"I am letting some of the odor escape here because in this very laboratory it was that the thing took place, and it is one of the well-known principles of psychology that odors are powerfully suggestive. In this case the odor now must suggest the terrible scene of the other night to someone before me. More than that I have to tell that person that the blood transfusion did not and could not save him. His illness is due to a condition that is incurable and cannot be altered by transfusion of new blood. That person is just as doomed to-day as he was before he committed—"

A figure was groping blindly about. The arsenic compounds with which his blood was surcharged had brought on one of the attacks of blindness to which users of the drug are subject. In his insane frenzy he was evidently reaching desperately for Kennedy himself. As he groped he limped painfully from the soreness of his wound.

"Dr. Harris," accused Kennedy, avoiding the mad rush at himself, and speaking in a tone that thrilled us, "you are the man who sucked the blood of Cushing into your own veins and left him to die. But the state will never be able to exact from you the penalty of your crime. Nature will do that too soon for justice. Gentlemen, this is the murderer of Bradley Cushing, a maniac, a modern scientific vampire."

"Dr. Harris," accused Kennedy, "you are the man who let Cushing die!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.