RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an picture generated with Bing Image Creator

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an picture generated with Bing Image Creator

JOCK McNEIL was only 23, a year out of Columbia, and a rather brilliant assistant pro at the Burning Bush Country Club, when he made the curious discovery. Of course, that was way back in the beginning of the Twerpy Twenties.

Then, even assistant pros were paid good, substantial salaries, got married, and generally looked forward to hitting the jackpot the way Gene Sarazen, Mac Smith and others were doing.

But Jock and his wife Rennie were cautious people. They believed in frugality, growing bank accounts, and decent living. So even in that era of wild spending. Jock had a habit of tampering down the load of tobacco in his pipe, and smoking many matches for each filling. The club furnished matches free...

Rennie sewed most of her own clothes. She put new collars and cuffs on Jock's dress shirts, darned his sweaters, and even rewove his plus-fours when he snagged them on a fence nail. Jock always seemed better dressed than even Alex Jaxon, his chief.

When Jock Junior came. Rennie made all his clothes. Jock gave the baby a couple of new repaints to play with, and talked about cutting down the shaft of a light gooseneck putter for the infant to use, soon as he could toddle erect.

The family budget became more carefully audited than ever. Jock now banked an additional five per cent of his salary and lesson fees. The saving, of course, was sacrosanct. No matter what else pinched, that came first.

It was funny, too, just where the worst cases of self-denial arose. Always on the smallest, unremembered items. Rennie would run out of cleansing tissue, or face cream, or would need a spool of white thread, or a new double socket for the vacuum cleaner, or they would use up the last tooth powder just when the exchequer was down to 9 cents on the afternoon before pay day.

With any other people those minor crises would have been met by a to-heck-with-it gesture. But then the other people, on the same income, would not have been looking forward to college for each child in turn, a competence for old age for themselves, and a stake for each youngster who wanted to go into business in later years.

Once on such a day of poverty, Jock walked six miles each way to the North Shore Club on Long Island Sound to get a bag of clubs for a member and patron. The bus fare had been 15 cents each way. This in the Lush and Twerpy Twenties, remember!

It had been just before then that Jock made his curious discovery, the tiny, incidental one which later would bulk so large to him. He had a sandy red beard, rather luxuriant, which he had to shave every morning—and then again in the evening, if he was to make any sort of social appearance.

But he did not go out very much of nights, things being as they were.

However, one morning of July 1—and the year might have been 1923—Jock put a new refill stick of shaving soap into his nickel-plated holder. Oddly it flashed to mind right then that it had been exactly six months before, to the day, when he had put in the stick that now had shrunk to a wafer, and vanished in lather.

The years came, and the years went, and always now on exactly the first of January, and the first of July, it came about that Jock put a newly purchased refill stick in his holder.

Once or twice there had been the wraith of the heel of a stick left, but so little Jock felt reasonable as well as generous with himself, in tossing it away.

On a couple of occasions, particularly after he became chief pro at the club, and won the Metropolitan Open Championship at Salisbury, he had a good many club dinners and other festive evening occasions to attend. These meant extra shaves, of course, and so along toward the last fortnight in June, and the last two weeks of December Jock would have to take his knife, carefully unscrew the bit of soap remaining in the end of the holder, take off the tinfoil, and then soap his wet beard with the inch of soap flake remaining.

But even if he had to get along with a rather light lather a few times, he made it a private fetish never to touch the newly-purchased stick until the dawn of the first of the month—January or July. In time he became highly pleased at the automatic way this worked out.

It was one of the stanchions of a sober, quiet life—and it remained, even after the bank and two mortgages the McNeils owned were defaulted in the black days of 1932.

Jock's salary was cut in half, and for a while it looked as though golf was something that had passed forever out of American life. There were two more young ones now, and Jock Junior was 12—a bright lad, ready, able to break 85 on the 6,850-yard course.

He was good in school, of course, and just now had been doing something rather shocking to Jock, but which actually brought in some money at a time it was gravely needed. And Jock somehow always had been able to manipulate his Puritanical conscience a trifle, when that meant money coming in rather than going out. The other way around? Never!

The lad had been taken by a play producer, and was one of a gang of 12 appearing in a show similar to "Dead End."

For this the astonishingly liberal play producer had been willing to pay $50 a week, as long as the play remained on Broadway. And it stayed 19 weeks.

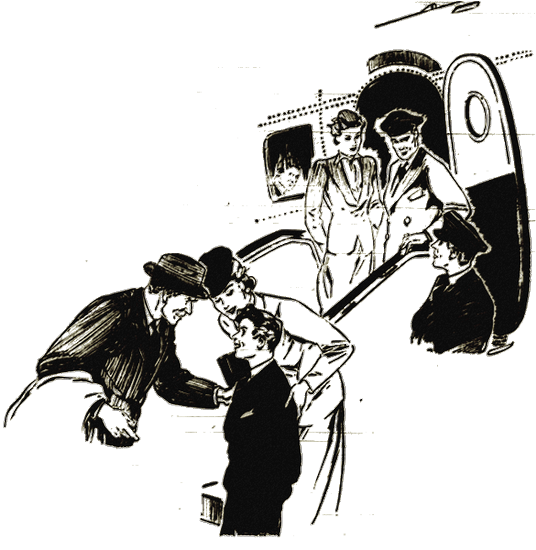

That was not all. Right then, realizing that this tough kid drama was a new bonanza, Hollywood movie producers leapt to bring out films based on the same formula. Since there were nowhere near enough child movie actors to go around, they flew east and hunted down all of the youngsters who had been playing in the legitimate dramas.

Jock Junior, attended by Rennie, flew west on a six-month contract, during the life of which the 12-year-old was to receive the astounding sum of $250 a week! It was more than Jock had earned, even that single golden year when he had won the Met Open, and been runner-up in the National Open Championship!

The old man was proud, but disturbed. He missed his wife and boy. The two young ones now were being ably tended by his wife's maiden aunt, and were getting along all right. But no one paid much attention to Jock. He sucked on his empty briar, and brooded.

Things in the golf world were going all to pieces. He did not even write the dismal truth to his beloved Rennie, when the exclusive Burning Bush Club opened its gates to greens fee visitors. Jock's salary had been cut to $2,500 a year, and there was practically no chance to make additional money out of lessons any more. Jock felt smirched and disgraced by having a child of his helping to support the family.

But worse things were to come. Even when his first contract ran out, Jock Junior stayed in Hollywood. He was going to school there, in a private progressive school attended by many other child actors. Also, every now and then he received a short contract for a single picture.

This was enough so Rennie and he lived on a scale shocking to the cautious father, who had little idea of how much a prosperous front counted in the movie capital.

Then, playing opposite a little girl with golden curls and a wistful smile, the adolescent Jock Junior made a great hit in a Tarkington picture. Immediately there were fat contracts offered on each side, and Rennie calmly chose the most advantageous. When her lad was signed up for two years at $790 a week, she sent for her two babies and the aunt. She wanted Jock to come also, but the pipe-smoking Scot would have brained himself with his own No. 6 iron, rather than live a week on money earned by one of his children.

The next Winter the Burning Bush clubhouse, that luxurious but undoubtedly ancient frame structure burned to the ground, it was found that the insurance was only $40,000 and that a modern clubhouse would coat $300,000 and take a full year to plan and build.

Meanwhile Jock was out of a job. He went around, applying everywhere, but no one needed an assistant nowadays. He grew more dour and gloomy, gave up smoking, and almost gave up eating. The future looked black indeed. When the new clubhouse was a reality, he could work again. But a whole year living on savings? Mon! Mon!

About the first of June. Rennie, her eyes alight with love, unexpectedly appeared to throw her arms around her stocky husband. The aunt with Jock Junior and the two youngsters were coming in a cab. She had just had to race to Jock... and tell him they had a whole month now of vacation, before work on Jock Junior's new picture would start.

This would be the last one for four years, too. He would go to college, and there would be a place for him at the end of that time if he wanted it.

"And dear!" cried the woman, "there's a bit part for you in this next picture! All you have to do is play a few shots In front of the camera. The hero will win, of course—but will you accept $200 a week for 12 weeks?"

"Hrmp," said Jock. "Is the money good?"

So it was that Rennie gave the house a whirlwind cleaning, incidentally throwing out a whole half inch of shaving soap which Jock was hoarding. Of course, she had forgotten his fetish.

Of course, Jock found out next morning, and was disturbed. A habit of years had been broken. But Rennie was talking, as he scowled blankly: "You'll have to have a bit of a beard in the picture, Jock dear," she was saying. "You're an old-time British pro. You better start letting it grow now..."

Then she looked up startled, as the dour man, suddenly relieved and happy, grabbed her in a fierce embrace and kissed her.

He would probably never tell her, but in actual fact he was happiest about not having to shave for a while. The loss of that heel of soap would not matter now. He could get back in the grove again, and even be a little bit extravagant about shaving soap, through the whole of a new six-month period!

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.