RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

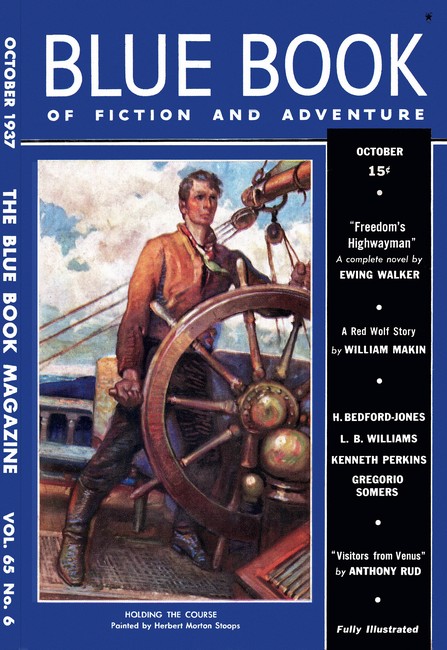

Blue Book Magazine, October 1937, with "Visitors From Venus"

The extraordinary story of the weird and malevolent beings

from another planet who descended upon a New England farm.

LOOKING out of the window, I can see Mt. Greylock of the Berkshires of Massachusetts. I have my typewriter here in an enormous new chicken-house—never used for chickens.

My hair stands right up on end when I think back to last summer—when I think why there never were any chickens to put in this large, new and splendidly-equipped house—and why every feather of the eighteen hundred hens in the other four chicken-houses was destroyed.

I take a good deal of credit for having any garden at all this spring. My nerve is better. Annie Overalls, the giant swamp-Yankee woman who does my plowing and harrowing, is out there now behind her team, turning over the soil for the truck-field. Annie weighs over two hundred, and has been plowing for thirty years. Just the same, her hair was midnight black this time last spring.

Now it has a wide white streak, pure white. And there is a sullen, slightly distrustful look in Annie's black eyes, any time she runs the apex of the plow into a root or some other obstruction. This land is damned, she says.

Annie never knew Dr. Armstrong—Charles Llewellyn Armstrong, D. Sc., and all the rest of the alphabet. I did. He was why I came here last year. He tempted me with a mystery. It tempted him too, and that is why he died. I am alive—by but the margin of a frog-hair.

Chuck Armstrong taught astronomy at State when I was a freshman there. He was the youngest full professor of that science in the country then, I believe. He awed me. I did well enough during my four-year course, so for one year I was a fledgling instructor under him. But then I went to writing and editing.

Doctor Armstrong's way led him further and further from the affairs of earth, and into attempts at short-wave communication with planets and even the nearer of the great stars. I have no doubt at all that by the standards of clerks and hinds, he became so obsessed with universal affairs, that in the eyes of the world he would have to be called crazy. Great astronomers cannot think in terms of glove-sizes and forty-quart milk-cans. They see a million miles, or a million million, and think in terms of light years. What price the short-ticking stop-watch of man's terrestrial existence?

TWENTY-TWO years passed. I was at Key West when Armstrong's telegram came. If I quoted the words, they would mean nothing. Suffice it to say that once long ago he had promised me a breath-taking thing. "I'll call you to help, Tom, when I get through indisputably to people of another planet, or get word here from them. Then you'll come, no matter what you're doing."

I remember how I chuckled to myself when I made that promise. Sure, I'd come—any time we had Mars on long distance.

That high noon, with the early spring sun pouring its rays like molten metal upon the sands of Florida's tip, I read the yellow sheets—three of them—of his night-letter. My eyes widened.

Somehow I forgot to chuckle. I had learned a few things in the intervening years. I felt chills skitter across my shoulder-blades; but at the same time my stomach felt as though it were blanching like an almond. Either Armstrong had gone downright mad, or—or else here was something that would make Leif the Lucky, and Columbus, and Stanley and all the other explorer lads look a dime a dozen.

Here was a man who claimed to have received a shipment of goods from the planet Venus!

Of course his telegram was couched in words such as we had used in the observatory, and which meant little or nothing to the telegraph-operators. Doubtless they thought it code.

I WENT by air, changing once. I landed at Canaan, Connecticut, one afternoon, then took a livery car (as they call cabs here) a few miles across the Massachusetts line into the heart of the Berkshires. The snow had gone, but only recently. It was chilly, though the sun was warm. Some plowing had been started, though only foolhardy farmers would put in anything like a crop far at least another month....

The Doctor had been near Flagstaff, Arizona, when it happened. I may as well say that the projectile from Venus missed the Southwest by a few thousand miles, and landed in New England. The Doctor knew all about it, though, and was on his way in a fast plane before the dazed natives of the Berkshires had got around to investigating. A little quick buying at a high price, no questions asked, and the Doctor owned one hundred and sixty acres, part of which had been used as a budding chicken-farm by an old fellow named Sassenach.

THE Doctor's second wife had died. Her mother, a worldly-wise frivolous creature—I had never liked her much—had spent a good many years moving from Monaco to Cannes to Paris to London as the seasons changed. She was about as much use on a farm as a spare tire is of use to a rooster.

Her granddaughter Helen—well, sometimes something good cometh out of Nazareth, and the most unlikely people are the ancestors of angels. That's how I felt at first sight of Helen, anyhow. I'd never particularly liked the name of Helen. Now I understood the Siege of Ilium, and all that. Helen was not very pretty; she was just a smooth and lovely blonde, built by a master sculptor with Eternity on his hands, and strangely enough endowed with sympathy and understanding. She could even understand her father and love him. Mighty few could have grasped his immensity, any more than they could have understood Copernicus in his early day....

Just a few days before Armstrong brought his two womenfolk, buying the farm, and installing the half-fitted hired hand to take care of the chickens till I arrived, something awesome and frightening had occurred in the still snowcapped Berkshires. A meteor had fallen.

Now, this was no ordinary shooting-star, to blaze a second or two in the night sky and then be consumed. It did not blaze at all. No one saw it—though they heard and felt it strike, that morning at two-forty-five.

It came at terrific speed, and in a slanting direction. Not straight down, as a baseball falls if you drop it from a third-story window, but at an angle of incidence probably no greater than twenty degrees. This slanting hit, of course, was due to the rotation of the earth.

As luck would have it, the projectile (I am admitting from the first that it was sent deliberately from Venus, though I did not believe that myself for a long time) struck rather lightly on the bare granite side of Ranger Mountain. It ricocheted like a flat stone shied across the surface of a pond. It narrowly missed Music Mountain, and then zipped a distance of some forty-odd miles before it lost elevation in its new trajectory and sought earth again.

Its final resting-place was this farm, of course; but before arriving to gouge that long furrow in the heart of the maple and pine woods beyond Dog River, it played a couple of strange pranks:

A brick silo on the Swanson farm lost the top twelve feet of its trim tower. And if Ole Swanson, who owns the most prosperous grazing farm and Holstein herd in Sheffield, was not known to be rich, his agonized Skandahoovian curses would have been pitiful. Doctor Armstrong sent him a fifty-dollar bill in a plain envelope, and worried no more about Ole. Probably he is still invoking Wodin and Thor with his billyboats, and wondering just what happened.

Two miles farther along toward this place, having lost about ten feet of altitude, the speeding projectile neatly lifted one small new automobile (untenanted) from the top of one of these big trucks which deliver four new cars to dealers. I understand that the driver felt a jar, but thought nothing of it—until the driver tried to deliver four brand-new cars to a dealer at Egremont later that morning, and found only three cars left. Then there was hell to pay for the driver, and no mistake.... I don't recall what Armstrong did about that, though he probably got the man another job.

UNLIKE that first slanting hit on Ranger Mountain, when the meteor-projectile crashed into the maple and pine woods here at Dog River, it caused no great noise or earth tremor. The top-soil there is soft—ten eons of pine-needles lie rotting there, and the earth below that is sand, gravel and clay, the bedrock being nearly forty feet down. The meteor lost impetus and stopped, long before it got to bedrock, thanks to the ricochet, and fortunately for the Doctor and myself—or unfortunately, if you think human life precious above all else. I don't—though I value my own, and the lives of those dear to me. In the abstract, though, and to others on this earth, I and my sweetheart are worth mighty little. We are too much in love with each other. Yes, even if I am in crusty middle age, that seems to be true.

ARMSTRONG, discouraging Sassenach and other people who tried to be neighborly, had hired just the half-wit called Ranny, and told the womenfolk to use his car, get groceries, ice, meat and whatever, allow no deliveries (there were none anyway), and to keep house for a little while as best they could. I was coming and I would help. (It seems he forgot that I had turned writer, and described me as an instructor in astronomy who had been with him years ago. This explains Helen's eyes going wide, when I arrived in the most unsuitable attire imaginable. I had on a Palm Beach suit and Bangkok straw—and a cheap, heavy overcoat and gloves hurriedly purchased. The rest of my stuff was coming by express.)

"Why—Mr. Cattell!" she gasped, when I had mentioned my name and asked for the Doc. "I—I thought you—were old! You—oh, excuse me!" And she blushed, putting one hand on my arm and leading me in to the small living-room of the farmhouse where sat cross, tired, and frizzle-haired Grandma.

The old lady's name was Mrs. Kramer, if it matters. They called her Nana, which made her furious. She was going "to get right out of this horrible place" just as quickly as possible, and go back to her dear Monte Carlo.

Well, she got out fast enough when the time came. But her destination was not Monte Carlo—unless that rather rundown gambling resort has changed a lot since I last saw it, and has become a suburb of one of the after-worlds.

I could forgive Helen, all right, for considering me not old. Any man of forty, slowing down a little in his tennis-game, and going a trifle thin on top, could forgive a lovely girl for making that mistake. I may as well say right out, I fell in love the first minute I looked into Helen's blue eyes. I'd done it before, with all manner of eyes, of course; but somehow it never seemed to last. But there is a certain stanchness and sweetness about blue eyes. You—But I'll stop raving now and get to my meteors.

I had supper, listened to Mrs. Kramer complain, and then got out hastily. The Doctor had not appeared.

"He—stays out there!" whispered Helen, touching my arm as she came out into the dusk with me. "There is a lantern here, Mr. Cattell—"

"The name is Tom, Helen," I dared. "D'you mind?"

"I'm glad, Tom," she said quietly. "I was scared. Tom, what has he got, out there? He won't tell us, except it's some kind of meteor. Is—is it very valuable, do you suppose? Made of radium, or something?"

"I don't know—but I'm going to find out right now," I told her. "Which way do I go?"

"I'll show you, but I'm not allowed to go out. When you go, whistle a tune. Do you remember 'Men of State'?"

Of course I remembered the old college song. And regretfully taking leave of the girl, who stayed there on the west bank of the small river, leaning against a stone fence, I distrustfully crossed the swinging footbridge, a suspension affair that swayed a full yard sidewise as I inched across.

Beyond lay the gloom of the woods. I lighted the lantern, started whistling, and then looked rather alarmedly at the straight bore through the wall of trees. Certainly some large meteorite had done this—and it was coming to earth when it did! Just thirty yards back in the close-thatched woods, where a man had to break branches from in front of his eyes continually, the first slanting gouge in the soft topsoil appeared.

Why, the blamed projectile, or whatever it was, must be as big around as a wine-tun, and smooth! The earth had fused until it was hard and almost like glass, there where the hot body from the stratosphere had struck!

Just as I reached a spot where the glazed furrow was five feet deep, I heard a short growl on the ground surface right beside my shoulder. A truculent white English bulldog stood there, evidently just about to take a jaw-hold on my neck!

"Down, Lord Nelson!" came a brusque voice. "You, Tom—and thank the Lord you didn't waste time!"

Bearing another lantern, the short, rather paunchy figure of Dr. Armstrong—terribly ravaged by the years, from the man I had known—strode up, reached down a grimy hand, and clasped mine, shaking it and helping me climb up out of the bore, at the same time.

My old professor wore glasses now. He was hatless, and he wore old brogans and overalls, dirt-stained from digging. But his voice was just the same. Perhaps a little graver, but with a restrained triumph ringing through it every now and then.

Certainly he did not seem in the least mad, was my first reaction. And I was relieved. Then I began to get really excited. If he was not mad, then could this incredible tale have any vestige of truth? Had he really got something, even a meteor, from Venus?

A LOT of what followed, I must compress. The Doctor wasted no time in reminiscences. He took for granted that I was there to help him in every way, and simply commanded my services wherever he wished them. Largely because of the lovely girl I had left back there at the stone fence, I made less remonstrance at taking up chicken-farm duties, than you would have thought.

Sitting down at the side of the bore, with our two lanterns and two pipes burning, Dr. Armstrong told me hair-raising things. Most of them have been published in the scientific journals, and I can skip them—furnishing a bibliography to anyone who cares to read back through the months and years, of his scientific claims. Most of them were laughed at then, I must admit.

Now, no one laughs. Dr. Armstrong was not lying. He was not even exaggerating. A few of his inferences were faulty, but in the main the terrific and incredible tale he unfolded was nothing more nor less than the simple truth, as far as it went. But even the Doctor did not guess now the hellish trick that had been played upon him by the Venusians themselves!

"I have been in communication with Ooloo, the highest-powered of six message-sending stations on Venus, for thirteen years," he told me curtly. "This is the result—" And he waved a heavy hand toward the furrow. "Somehow, Tom, I am almost afraid to dig further. I'm going to dig, all right. But I have found out that the Venusians are scarcely people at all, as you and I understand the term. They are intelligences, all right. Far ahead of us. But I—well, I have not the faintest idea in God's world and universe, what a single Venusian looks like!"

"But—but isn't he a person? Isn't he a man?" I cried rather blankly. "What on—that is, what else could he be?"

"I don't know. A machine, perhaps. A sort of fish with a brain. A great pterodactyl, maybe. Anyhow, I pin my faith on the fact that he does have a brain.

"It is a highly developed intelligence, too. I think the Venusians live in caves, or have underground houses. Yet they knew about us, all right. I can't seem to get much out of them, though they accept and acknowledge all my messages, as if they understood perfectly.

"Lately, for over a year, they have sent me brief ether-waves which I have understood as meaning that they were building a great catapult or gun, and would send me on earth a shipment of goods of their own manufacture—or possibly, produce from their fields. I am not sure which. They have some way of shipping things in asbestos or some similar material, so it is not consumed by the heat of passing through another planet's atmosphere.

"In fact—well, down here a few more feet, is that shipment! Can you imagine, Tom Cattell, what we are going to find when it cools, and we can open it?"

NO use trying to tell anyone else the thrill those words gave me, as I stood and looked down in lantern-light, in the midst of the dark woods, at the place where the furrow stopped, and the great projectile had burrowed on in an underground bore. But I could only stammer at the time. I was frightened, and at the same time so fascinated that I could not have left that thing, even had I been sure my own life was going to be forfeited to further curiosity.

I found out now, though, that I was to do no digging. The Doctor would call me fast enough when he really got to the projectile. But he estimated that there was more than a month of hard work here for himself—and meanwhile I would have to run the chicken-farm as a sort of blind, and see to it that the two women did not suffer. The Doctor had found a deserted cabin back here in the brush, and stocked it with bottled water, beer, tinned food of all sorts, and brought some bedding. He intended to stay till the job was done. I could come once a day, after nightfall—no other time unless he called me.

THINKING of Helen, I was torn two ways. But I agreed reluctantly, and wended my way back with the lantern. Certainly I had never thought that the young woman would still be waiting for me, after a good two hours, but there she was.

"Tom!" she cried chokingly; and she grasped my arms.

"Why, Helen!" I breathed, feeling that she was trembling from head to foot. "Why didn't you go back?"

"I—I'm afraid!" she whispered. "You—you are the only sane man around! I—" And then she hid her face in the lapel of my jacket.

Well, I'm human. I kissed her—idiotic though it may sound, after knowing the girl only about three hours. But I did, and she was modern enough not to mind. In fact, she seemed to take a certain comfort from it, though she speedily drew away a little, and did not allow any more of the familiarity. I know now that she liked me at first sight; but that, womanlike, she needed a certain reassurance that normal, human things like love and sympathy and understanding, still could influence a man, no matter what queer visitors came from Venus or anywhere else in the heavens.

And I must say that I walked on air. I was really in love for—well, I almost said for the first time. For the greatest time, anyhow! If that be treason to science, make the most of it. I was only an ex-astronomer, anyhow.

Doctor Armstrong intended to keep his secret. He worked harder than might a section-hand on a railway, and the work changed him. He always had been clean-shaven. Now he grew a white beard; it was stained yellow around his mouth from his incessant stogie-smoking. His paunch shrank. He hardened, of course, but somehow seemed to grow frailer instead of stronger. He was too old for the task he had set himself; but every time I offered to take his place, a certain fanatical zeal, and a light of what I came to know was genuine apprehension, blazed in his eyes.

"Never! This is my responsibility, Tom!" he would say firmly.

He ate supper late. I took to bringing him over hot meals from the house in a basket, then sitting down and listening—after telling him of Mrs. Kramer and Helen, and how I was getting along with the half-witted Ranny, and with the eighteen hundred hens. Those damned chickens really kept me busy. In the state of mind I was, loving a girl and waiting with trepidation for the wild cry from Doctor Armstrong, telling me that the meteorite was uncovered, I needed hours in which to accomplish an amount of work which normally I could finish in a half hour any time.

In order to make the place look like a real farm, I had engaged a giant swamp-Yankee woman, nicknamed Annie Overalls, to plow and harrow a truck patch. I would seed it, with Helen helping. It amused her, and provided something to busy her mind. She was glad, too, to have an excuse for getting away from Mrs. Kramer.

IT is the almost incredible truth that, lulled by the routine of the Doctor's steady digging, by the work of seeding a truck-patch in the company of a laughing blue-eyed miss who nevertheless could accomplish just as much as I at that sort of bending-down work, and by the responsibility of marketing eggs and broilers and caring for so many chickens, I really began to discount the matter of the Venusian projectile said to contain a shipment from that planet. Yet all this while of fool's paradise, more than two hundred thousand loathsome things were waiting down there—held by a high pressure of indrawn breath, in that queerly constructed cylinder below-ground!

Waiting to destroy me, the Doctor, Helen, Mrs. Kramer, Annie Overalls, the half-witted Ranny, and every other human being and living thing on the face of Mother Earth!

The Doctor had given me a hint. But he did not understand it himself, and of course I paid no particular attention—then. In the unsatisfactory, one-sided communications he had established with Venus—the Venusians would ask all manner of questions, but tell little or nothing about themselves—Dr. Armstrong had noted that their interest lay chiefly in the soil of the ground, and in descriptions of the living vegetation and animals upon the surface of the world.

"They don't seem to understand when I talk of cities, airplanes, skyscrapers, locomotives, and other things," he told me. "They seem to have an avid agrarian interest, however. I have sent messages of description as long as the ordinary juvenile encyclopaedia, and they never thank me. They always ask more questions. They never answer the things I ask—or only partly. I—well, to be frank, Tom, they have me worried. I fear they have no souls.

"Yes, I fear—worse than that! I have an idea that their intelligences are motivated by selfishness and a sort of hellish cruelty only! I do not think we would like the men and women of Venus, even if we ever managed to see one. And this shipment of goods on consignment, you might say, may turn out to be some devilish joke—a shipment of troubles worse than those which were held tightly in Pandora's box!"

"Anyway, we'll have a look," I chuckled—little dreaming how much more horrible than his wildest guess, the truth would prove to be!

I tried to let him rest while I dug a couple of evening hours—not that I care for digging and hauling up buckets of gravel—but he would not allow it.

"Something is going to happen, when I reach that cylinder," he told me solemnly. "I am not quite sure how soon I'll reach it. You see, the bore curves to the left? Well, I think the cylinder is about twelve feet more down; over there. But it may be closer. If—if something awful is there, Tom, I want it to act on me. You are young. You can see the women safely away. Uh, by the way, do you find my daughter at all—um, I mean—she is pretty, isn't she?"

THE old man actually had feelings! I colored, though in the lantern-light I don't believe it showed under my tan.

"Some day I'm going to marry Helen, if she'll have me!" I said. "Too bad I didn't see her ten years ago."

"When she was twelve?" he asked. "Oh—I see what you mean. Nonsense, Tom, you are young—young. Wish to God I were, now, though I never have regretted the years and what they have brought. This discovery, and possibly the contents of this projectile—"

He fell silent then; and I left him.

And the next day, early in the morning, the Doctor unexpectedly uncovered the end of the giant projectile!

HE did not let me know. I was busy. Helen had wrenched her back, and I was lame from hours of planting. So I had got Annie Overalls to finish up the truck-patch seeding. The first things I had planted, the lettuce and peas, were coming up beautifully. Annie shook her head and said they would get frosted. But I did not care much. After all, this farming and chicken-raising both were parts of an elaborate camouflage. The odd part was that I had found out I liked them. So did Helen. She never would make a farmhouse woman, a drudge, but for the playing at farming which most city people do, she was splendid, enjoying everything. I had begun to visualize life with her in a place a whole lot like this, with some one more capable than poor Ranny to take care of the chickens, while I went back to writing for five or six hours a day....

That day, for the first time, through the coincidence of a message regarding a Venusian communication—a message for the doctor sent by his assistant left behind at the Ajo, Arizona, inter-planetary radio station—I hurried out at midday to the diggings in the pine wood.

I whistled. The dog came up, growling uneasily but wagging his stub of tail. Then I heard the gasping breaths of Armstrong. He was down at the foot of the ladder, shoveling away like mad to uncover more of the great cylinder.

Now I saw it, and gasped. The thing looked as though the outer shell was made of a soft sort of concrete. But it was covered with a bluish-green flame all over—something like phosphorus, perhaps, though it was perfectly plain in daylight. It was still hot. The Doctor heard me.

"It's here! See, Tom!" he croaked, in a voice gone fog-hoarse with emotion and triumph and apprehension all mingled.

"I see!" I cried. "Good Lord, what is it? Is it burning?"

"No. That is a cooling flame, I think. This—this is made by men of some kind, Tom! You see? Look at this great seam? I—I believe the thing is going to crack open when it cools some more! See that jagged line? It is a crack!"

We were both wild with excitement now, the message from Arizona forgotten.

The cylinder, as we found out immediately, had been equipped with a disintegration mechanism, doubtless chemical, which began to act immediately the great shell struck Earth, much as a high-explosive shell of the kind used in war, works, only much slower. Hours were required for this, instead of from one to four seconds. Now the blue-green flame, which oddly seemed to cool and shrink the outer shell of the projectile, making it crack widely, was busily at work on every square inch of the cylinder exposed to air.

MY description must be sketchy, because of the fact of fast disintegration. If we only had been granted days instead of hours for examination! But there was a reason, known only to the cold-blooded Venusians themselves, why any inter-planetary shell of this kind, could not accomplish its hellish purpose, unless it cracked and crumbled like a big piece of sugar under a hot-water jet. And that is what this proceeded to do.

The Doctor had a sort of adze. He struck at the crack—and a whole chunk of the substance crumbled away!

"It's all going to pieces!" I cried. "The goods inside will all be spoiled before we can see what they are!"

"I don't think that, Tom," he replied, standing back in the bore and shaking his head so the white beard swayed. "Maybe that would be far better—or a few sticks of dynamite right now—"

"Oh, for the love of Rameses!" I snapped impatiently. "Are you sun-struck? Here we have a chance to see just what this is, and you mumble a lot of nonsense!"

He was filled with forebodings, though, and for twenty minutes I argued, to dissuade him from doing anything rash. All this while the disintegration was going on apace, though we could not guess how thoroughly it was working. The outer shell remained about the same, except for widening cracks.

The cylinder—a few feet of which still remained covered by earth—was about twenty-eight feet long, and exactly seventy-eight inches high at the base as it lay on its side. I measured it. Roughly, the thing consisted of several layers of material, non-metallic by nature, which acted as a heat-resistant and insulation against cold for the inter-planetary flight.

Inside these several layers (and now I am giving pure inference, since I never saw with my own eyes what was there) was a relatively small cylinder, perhaps the size of a sixty-gallon hot-water tank of the old-fashioned sort you used to see in farm kitchens, hitched up to the stove by a coil of pipe.

This was of strong material, possibly metal. It was built to withstand a terrific pressure from within—but to let go when the cooling of the outside shell, and its disintegration, had proceeded to a certain degree. Maybe there were delicate cocks, and a release as sensitive as one of the thermostats we have on our oil-burners. I think that very likely.

"I think I will try to crack it open, then," said Armstrong at last. "I do not like how it is going, though as I have said, it might be far better for us—and the world—if it was destroyed right here and now. However, I have worked forty years for this, and at Ooloo on Venus—"

He raised his adze, hesitated, and then brought it down on that inner layer from which the crumbling flake had dropped away.

The adze went through just as though it had been cutting into husks! A huge piece fell away. Now a blue-colored layer appeared below. The blue-green cooling flame ran down in rivulets, attacking this hidden layer with a hissing and crackling avidity.

The Doctor sniffed. "No fumes that I can smell," he muttered, and raised his adz again. Down it came—and then the horrible end! The blade of the tool sank so deep that Armstrong's fingers almost followed the handle into the soft, oozy stuff that now bubbled and began to pop up spats of viscous bluish stuff like the mud-pots of Yellowstone.

zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz!

Up and out of the cylinder came a thin jet of vapor, almost colorless, though in the daylight there was a faint greenish tinge.

"I think I got clear to the middle of it!" yelled Armstrong, highly excited. He jumped back out of the way of that jet of vapor, which at first just played up about a yard, then wafted away in the slight breeze.

But then gasps came from us both. The hissing heightened to a whistling scream! Up came green vapor now like a geyser! It mounted eight feet, fifteen, thirty—and it was blowing green fumes that were half-liquid, up to the tops and through the nodding plumes of the pine trees! The screech drowned our voices. We scrambled out of the bore, to escape. This might be poisonous, we thought.

It was worse than poisonous! It contained something—two hundred thousand things, I should say!

The first intimation came when a popping sounded, then another; then faster than a machine-gun chatters, the sounds came—and at each sound, something brown-rubbery, looking almost like a dead stingaree or a deflated football, was spouted and blown up into the air high above our heads!

"The cargo! What is it?" shrieked Armstrong, his mouth only a foot from my ear. I just shook my head dumbly, staring. I was truly frightened now.

BEFORE our horrified eyes, the great cylinder cracked and crumbled. The thin spout of geyser widened. Now the brown footballs were being vomited upward in a great cloud. I stared up at them above the trees. Then I shrieked, covered my eyes, and ran.

Those damned things were not falling to the ground! They were hovering there in a sort of immense swarm! And each of those near enough to me so I could see some details, appeared to be unfolding and shaking out creases, growing immensely larger, and lighter brown in color!

Panic had me. I brought up short when I ran squarely into a tree, and for half a minute or so I was stunned. Then I went back to the bore, but the Doctor was not there. He also had run, though not very far. He was out in a little glade in the woods, staring up at the floating amber-colored balloons—for that is what they seemed now. Second by second immense numbers of them were being vomited up to join their first comrades in the air; and the whole loathsome, shivery cloud seemed to float around an axis, or perhaps some kind of queen balloon, as bees surround a queen bee!

Probably the geyser of gas and cargo had been going full force about fifteen minutes, when I caught a lowering of the pitch of sound. Yes, the pressure was falling! The cloud of queer, light-brown things, floating now like gossamer scarfs, made practically a tent over this part of the wood, filtering down the sunlight in a tan haze. But the things were coming slower, the geyser rapidly falling. I did not guess the immediate danger, even when I saw a number of the loathsome things get only part way up to the main swarm. Some of them plastered themselves against branches as they failed to get high enough. And the last thirty or so were spewed up and out only a yard or so, and hung wavering and unfolding right there before my horrified eyes!

Oh, God, I was insane then for a time myself! Those damned things were alive! They had big spots like bull's-eyes, that stared unwinkingly at me! Seven eyes apiece! I shrieked and tried to run.

Let me forget that madness for a moment, just to tell you what they really were. Essentially they were slightly moist sheets of living fiber, when they came out of the gas-liquid in which they had traveled from Venus.

Yes, each one was a thin, translucent sheet, scalloped at the edges, oval in shape, and with seven eyes and a dark blotch near the edge at one place. As I know now, this dark blotch was a brain, an intelligence which activated the creature!

It was contained in a bag of this fiber, and was essentially a sticky, viscous mass no larger at first than a small grapefruit. (When the creatures were able to get water, or establish contact with earth or other food, this expanded quickly, as I shall show.)

These things, I believe, had been carefully dried out and packed in small compass, before being sent from Venus. If the soil and other food of Earth agreed with them, they would expand hugely, reproduce in swarms, and—well, you shall see!

A yell of terror and warning came then from Doctor Armstrong! He was out of my sight, behind some trees, but I heard the agony and fright. That same second a screeching ki-yi-yi came from Lord Nelson—one of the fearless breed of dogs, that nothing like an enemy on earth could cause to flinch.

With an answering cry, I started forward to help in God only knew what extremity. But I got only a few yards. Then I stopped, a screech of pure terror starting from my own lungs.

Something chill and damp had swathed itself, like the tendrils of a great goat's-beard jellyfish, about my left leg, side and arm!

FOR precious seconds, while my flesh crawled with loathing, I writhed and struggled against an impalpable but relentless foe. The thing knew its horrible business. It proceeded to swath my arms and legs, binding me stickily until I fell to the ground.

Then it threw a flap of prickly, stinging, malodorous fiber over my face and head! It was going to shut my nostrils and mouth, and suffocate me!

I could writhe, and move some. The fiber gave like live rubber. But I could not get it off my skin! Choking, smothering as I tried to scream, I yanked forth my pocket-knife and slashed at the horror. It cut easily—but that made no difference. Even the strips and tiny pieces clung to me—and then joined up again with the main body of the creature! It was almost like a great amoeba, offering small resistance seemingly, yet going right ahead to its horrible end, no matter what struggles its prey offered!

I could see those seven awesome eyes, hovering out there only a yard from my face. They burned with a queer green light. I felt my senses going. Damn them, they were gloating over me! I was to be a first Earth meal for this abomination of the Universe!

Pure luck, and the instinct which makes a man struggle—with his brain as well as his muscles—saved my life at the very last; perhaps saved all of Earth as well. I shiver when I think—

Anyhow, I was going. I could not breathe. I dropped the knife. One hand moved a little. It found my jacket pocket. It clutched something hard and heavy: My cigarette-lighter! I thought sickeningly but vengefully, "perhaps I can hurt this damned thing a little before I go!"... and I snicked on the lighter, forcing it outward toward those staring bull's-eyes of the Venusian creature....

Crackle-crackle-sssssssss—Whack!

A frightful stench came to my nose—and my nose was free to breathe! The thing twitched, convulsed, almost breaking my ribs. Then it let go, and floated away—and it burned swiftly, fiercely, almost as though it were a celluloid envelope lighted at one corner. It writhed on itself, beating its folds of fiber vainly against the flame. Its great eyes, which had no lids, gradually slitted to black lines—and then the fire reached them.

Only a viscous, sticky something dropped with a plunk to the earth at my feet. But it also was burning briskly— and in sixty seconds more there was nothing but some oily-looking char upon the grass! I was free!

BUT what of Doctor Armstrong? Still clutching the lighter, I ran to help him, breathing great gasps of the blessed air, and scratching my itching skin where the creature had set up some kind of inflammation and irritation.

Another of the creatures swiped its folds at me as I ran. But I saw these and dodged them. They did not move very fast, thank God. I wanted first to succor the Doctor, and his dog—not having a real chance yet to think of the even greater emergency pressing upon the girl I loved, and the others at the field and house....

Then a cry of anger and anguish burst from my lips. No less than three of the things had bound the Doctor. Another had the dog. Both were dead—though of course I was not sure until a moment later. In an instant, I had set fire to the folds of the things that had Dr. Armstrong. Whish! They burned fiercely, though they unfolded rapidly and freed him. He was scarcely scorched at all, as they floated away, squeezing their eyes to slits—I hope in plenty of pain!

But he and the dog both were stone dead, suffocated. They had been attacked before my particular foeman came after me; and the clinging folds had done their awful work.

I HATED to leave Armstrong there. But I saw something now. All the creatures remaining in the wood were wafting themselves slowly upward. They were joining the main swarm—a gigantic tent which now stretched like a manila envelope over several acres of the woods. I thought to myself, I would give ten thousand dollars for a skyrocket, right now, to shoot straight into that hell-born swarm of ghouls!

Then I noted something—and I think I leaped a yard from the ground and yelled insanely at the top of my lungs. The whole swarm was bound straight for the field, and the house where Helen and Mrs. Kramer were!

(I realize now that the things were aiming for the truck field. The plowed and harrowed raw earth attracted them particularly. But I thought only of the house and Helen. Wisely so, since there were far too many of the Venusian creatures to crowd down on the single acre of truck patch. They overflowed to the house-roof and porch, covered the chicken-houses—and a couple of thousand even oozed into the houses and fastened each upon one of my poor White Orpington hens! But I did not know that then.)

By sprinting, I managed to gain on the swarm. But I stumbled and went headlong, losing a few yards. And then when I came to Dog River, and the footbridge, the blamed contraption swayed so violently (it was made only for careful crossing) that I slipped and fell through the side. I splashed down into three feet of water, landing on my feet and not falling. But with anguished curses I realized that the damned swarm would get to the house before I ever could reach it! Oh, God, that Helen might remain indoors and close all the windows!

While I was scrambling up the bank, forcing a way through thorn bushes, and getting under way again, terrible things were occurring. I know that now. Then, when I finally reached the path, and sprinted, I saw the giant figure of Annie Overalls running blindly in my direction —and getting tangled up in a barbed-wire fence as she came.

The swarm had hovered, then descended rather swiftly on the harrowed field where Annie was seeding corn in hills. She had been leaning on her rake, staring up at the phenomenon—and only taking fright when the things started down upon her.

Poor Ranny had come running out of one of the long chicken-houses, gaping and gabbling in his weak-brained way. Waving his hands, poor fellow, trying to shoo the yellow-brown creatures away from his precious chickens, he went down under a smother of half a dozen or more of the Venusians. He was not even noted. He died right there, and was partially consumed before he was discovered. But that is getting ahead of the rapid-fire happenings.

ONE of the things had seized Annie Overalls, and had blinded her so that she ran straight into the barbed wire. I grudged even a moment, but her loud yells of fright could not be ignored. I ran to her, just as the smothering started. She had managed to tear loose from the wire, but now the folds of the Venusian had her, and she fell, writhing. Even her great strength, equal to that of two men like myself, was powerless. The moist, clinging folds of fiber stuff would not be denied.

Croaking out sounds that had no meaning, I snicked the lighter with trembling hands, and thrust it against the brown folds. They caught swiftly with a crackle and blazing. And then Annie was free, her eyes staring, and stentorian bellows starting again as soon as a few good breaths took root in her lungs. Then she plunged past me, and made a straight line across fields and fences. She got home, to tell one of the wildest stories ever heard by countrymen. But at the moment I was not caring about her further fortunes. I saw that at the house two figures in women's dresses had come out to the front, and were coming down to investigate just what was occurring in their plowed field!

I screamed warning—too late! Helen stopped, startled. I heard her voice:

"Tom! Tom! Come here! What in heaven's name—"

THEN, I give you my word, the most terrible thing of all happened. Those folded creatures had settled down, huddling in the soft field, swaying a little, jostling each other. The entire field, as I said, was covered, and there was part of a second layer of creatures on top of the first. These were Venusians denied access to the raw earth, from which they could draw quick nourishment—water and food. Almost as quickly as they could get it from the arteries, veins and flesh of a living creature like a cow, a chicken—or an unsuspecting girl come out to gaze upon the abnormal, unnatural wonder.

Helen and Mrs. K. had come down to within a couple of yards of the swaying, huddling mass. No doubt it looked innocent enough, if marvelous, to them. But the creatures saw two new victims—living victims from whom quick blood-and-flesh food could be taken.

A full dozen of the first comers to the field, now hauled up a multitude of white roots—water-seekers they had thrust down into the soft, sandy clay—and started to float toward the two women!

Of course I was running to help, sprinting around the acre field—it was impossible to cross, of course—but I knew I was too late, unless the women ran for their lives.

I screamed that command. They heard, and seemed to understand. They ran—but in opposite directions, and not very far. I had eyes only for Helen. I saw her stumble, cover her face with her hands, and fall. Then a cloud of those horrible creatures floated over and settled upon her quivering body!

There were about eight of them, I think. I got there, snicking my lighter—was it going to catch?

No! The thing took this terrible instant to refuse to light! I screamed, tore at the folds vainly, and then caught hold of reason. I searched my pockets fast. Ah, one match of the grocer's variety! Almost coolly, though my heart was dying inside me, I lighted it on Helen's heel—my own trousers were drenched, as were my shoes—and then held the flickering flame to those brown folds....

Whish! Crackle! Snap! The blaze started. The things unfolded and floated away, flapping vainly and squinting their terrible eyes. I waited for no more. I grabbed Helen, finding that her heart still beat fast, though she was unconscious, and ran from there with her. I think I ran a half mile before I dared put her down. Then I remembered Mrs. Kramer.

I raced back, leaving Helen, praying for her safety. I needed matches or something with which to make a fire. I dashed to the house, slammed inside, grabbed the phone, called the police at State police headquarters, and told them to come and bring the town fire department. Then I ran out to the back, grabbed a hatchet and a box of matches, and ran to the driveway at the side where the Doctor's car was parked.

Jamming foot on the starter, I backed the car to the field. As I had known only too well, there was no sign of Mrs. Kramer. Over there at one side, in the grass some yards from the field, there was a detached huddle of swaying things —maybe forty or fifty of them. No doubt she was underneath. But since minutes had passed, I knew she was beyond all human help.

I DROVE the car right into the edge of the Venusians. Then I leaped out, hatchet in hand. One swipe spilled open the gas tank. A thrown match—and the great fire cleansing started. The whole field and the chicken-houses went, just as fire tears through celluloid!

I could not watch, for several of the things had fastened to me. I had to light a separate fire to free myself—and it was hard to get movement enough of one hand, so I could light that match! But I did, and I was free.

Then I dashed to that separate huddle, while the whole field seethed in flames behind me, and lighted that. Yes, there was poor old Mrs. Kramer, singed now by the fire, but looking calm enough in death.

And far over at the other side, now that curling, charring folds of brown-black were floating upward and leaving the ground bare, appeared the body of poor Ranny.

The chicken-houses caught fire. But the fire-department boys, with their booster pump, quickly extinguished the conflagration. Then I had to explain a whole lot—and I am not going to detail that anti-climax. Suffice it to say that in a neighboring field the police and firemen found three cows being consumed by the creatures from Venus. When I lighted matches and burned up the folded horrors, they were ready to believe anything I had to tell.

I went back up the road, and found Helen stumbling pale-faced toward the house. Without a word I took her into my arms, and let her weep relieving tears.

THERE is little more to tell. Just one thing, really, though that is important. I sent a version of the story by air-mail to Alonzo Jordan, who had been Dr. Armstrong's assistant at Ajo, Arizona, near Flagstaff. Unwittingly, I caused a further tragedy.

Young Jordan sent news of the destruction of the creatures on to Ooloo, before anyone could prevent him. And it seems that a spasm of anger and horror swept Venus—horror that we on Earth had not simply allowed ourselves to be consumed by that colony of dehydrated immigrants they had shipped to us, I suppose!

Anyway, Ooloo berated Earth bitterly. It seems that there were some intrepid pioneer Venusians in that shipment.

After cursing us up and down, in and out for our "heartless cruelty," the Venusians declared a ban and taboo on Earth forever! They would not come to visit, even if we begged them—and they would execute any of us who dared visit them! They asserted also, that hereafter Ooloo and the five other inter-planetary stations would be closed to messages from Earth. In short, in the future they would have nothing whatever to do with us. We might consider ourselves ostracized.

When Jordan learned this, he carefully jotted down the messages. Then he smashed the sending- and receiving-station beyond repair. Finally he sat down and wrote this:

My life-work was with Dr. Armstrong. It is ruined, and I do not care to live. Good-by. Alonzo Jordan.

Poor, mistaken young fellow! He took that failure too seriously—since after all it was no failure at all, simply an experience. It showed us that one planet, at least, was peopled by creatures with whom Earthmen could not deal.

They found Alonzo Jordan with a bullet through his brain, and a pistol clasped in a lifeless hand.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.