RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

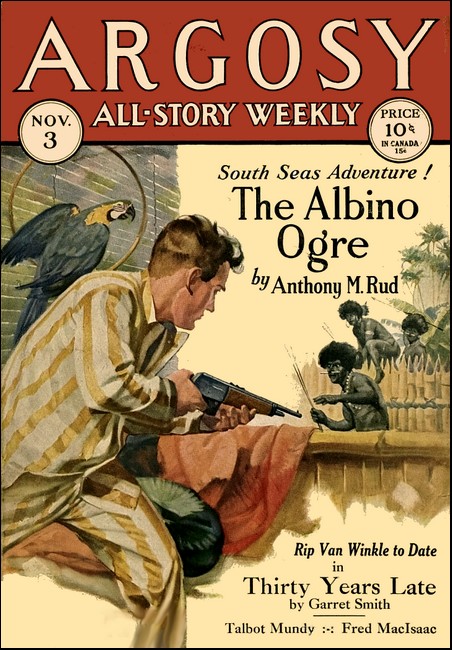

Argosy All-Story Weekly, 3 November 1928, with "The Albino Ogre"

Horrible and all-powerful, the ghostly shadow of Pappas the Pink fell like a deadly blight over the coral islands, transforming a tropical paradise into an inferno of terror and death.

ROTUMAH LARRY'S, on Kunufunuka, is a nipa-thatched "palace" built in apparent insecurity, twenty-two feet above the ground. Its supports—physically speaking, that is—are a number of slanting royal palms.

A guest reaches the bamboo and mat veranda through a chair-lift and pulley, slung through a sort of hangman's trap. The Melanesian blackboys hitch ropes around one of the more slanted, trunks, and run up barefoot, agile as monkeys.

Up atop the tallest of the palms is a kind of crow's nest. One of the coffee-skinned sons of Rotumah-Larry is up there day and night, using either the Zeiss prism night-binoculars, or the green painted Soderberg telescope which looks like a camouflaged three-pound fieldpiece.

From either of the two possible approaches to Kunufunuka the tree-hut cannot be seen. Any object—from the dorsal fin of a gray nurse-shark to the tracing of a British-French Commission cruiser—can be detected miles away. Because of coral reefs and treacherous shoals, no vessel larger than a flying proa or an outboard-motored canoe ever tries to come in after sundown.

And there are always enough grim-faced white men, Malays, and savage Melanesians, to repel a whole fleet of proas. Twice it had been done.

Rotumah Larry's was—still is, as far as I know—one of the eight or a dozen places in the South Seas where every white guest is guilty of a major crime—or, at least accused of one.

I was wanted for what the State cops called murder, back in Aurora, Illinois, U.S.A.

It was at Rotumah Larry's that I encountered Denmark. Queer name. Denmark Ordway Treleaven was his full name, though I didn't get to find that out for awhile. Those who knew him before I did—who knew him well, I mean—called him D.O.T. "Dot!"

There probably is no more metropolitan place to drink than Rotumah Larry's. Larry is a traveled man—and a wise devil, if there ever was one. To occupy one of his hideous bungalows back in the jungle of Kunufunuka—with a blackboy attendant and good tropical meals served—a guest pays forty crowns a month in advance. To drink on the bamboo veranda costs a great deal more.

So, within twenty-two feet of Rotumah Larry's ice machine, and nearer than that to his munificent bar, that I told my story of what had happened on the Gilbert Islands. Cannibals. Two matched pink pearls suited for the ear pendants of a maharajah's favorite. A thrilling escape in a lateen-sail canoe lacking an outrigger. A heavy sea. A swim ashore, holding to the overturned canoe, in which the gold fortunately had been lashed.

Two-thirds of it all was true; but little or none was believed. That was why I lived, perhaps. Midnight ding-donged from Larry's big gilt-copper ormulu clock. Long unused to any kind of liquor, I soon fell sound asleep.

"DRINK this."

Those were the first words I heard on awakening—though for what seemed hours I had dreamed I was in a combination tidal wave and earthquake. A complete stranger had been shaking me. Now he held a cool, frosted glass to my lips. I sighed, gulped a little of the slightly acid, fizzy liquid, then pried open my eyes.

For a little while I saw nothing clearly but the long, silvered glass. I drank—this time slowly and surely.

From the taste I was certain this was just what I needed. But I knew almost nothing about any sort of medicine or beverage except medicinal brandy, which I hated. Now I remembered with a shudder that always henceforth I should hate swizzles.

"W-what is it?" I managed to articulate. "Damn' good. What—"

"Ice-cooled tomato juice in a frosted glass. Like it, brother?" The resonant voice sounded tolerant, amused.

I groaned, tried to sit up—but fell back.

"Great stuff!" I managed to articulate. "Wish to hell I'd been guzzling that, 'stead of—"

I broke off, focussing vision upon my unknown friend.

"Huh—you weren't one of the crowd...?"

I made it a query. I wasn't at all sure. And impertinent questions asked of men who see fit to hide themselves south of Zero latitude are distinctly out of order.

"Oh, yes—there is nowhere else to go. If I had chosen I could have told just where your placer was located—eighteen miles up the Rakahanga River, eh? And you cached the nuggets under the roots of that breadfruit—

"Hold up!"

He raised one hand warningly as I jerked to a sitting position, fumbling for the shoulder holster still reassuringly weighted under my left arm. This was clairvoyance—or something far more sinister. Had I told all this in a drunken delirium? I gazed belligerently, suspiciously at my supposed good Samaritan.

"Besides," he went on calmly, "I took the precaution of removing the cartridges from your Colt. Please don't mind that. Not now—or later when I tell you something even harder on jumpy nerves. Gold is the last and least of my worries. At Suva, Apia, and Sydney I have substantial banking connections—and what need has a man of much money, anyway?

"The last time the Rakahanga River was worked for gold, four Gilolo Dutchmen built a sluice. Their heads are on poles in front of some Papuan chieftain's inspara now, I suppose. I arrived too late with my warning."

"But who are you?" I cried, sitting bolt upright and swinging my bare feet to the matted floor. My senses were clearing. Realizing that I was in the power of this stranger, at least for the time being, I scrutinized him with a puzzled glare I should have made an X-ray, had I been able. His gray eyes smiled back at me, but without ridicule.

NO, I had never seen him, to the best of my

knowledge. There, tilting back against the flexible

bamboo wall which gave several inches beneath the solid

pressure from the chair back, was a man considerably taller

than myself—almost six feet, or possibly an inch

more. He wore the lightest of native-manufactured bark

sandals on feet no larger than size nine. Small for a big

man—and he certainly looked big!

For clothes he wore a two-piece athletic suit, the trousers of sateen, black-and gray-striped vertically. The shirt seemed to be of cotton; and on the front of it a large block letter, a green D, still showed faintly after many launderings. What that signified I could not guess.

He was lean, yet there was a smoothness of sinewy curve to his forearms, biceps, and hairy legs which told me all I wanted to know. Show me a big, bunched-muscled gorilla in the other corner of the ring from me!—and I'll cut him to ribbons, probably knock him kicking in two-three rounds. But these resilient, easy-moving jiggers, with muscles that scarcely ripple their skin—

I watch them! One of them, a plain palooka, dusted me for the count once, down at East Chicago.

"My name is Treleaven—Denmark Ordway Treleaven. Get up now and wash. I'll tell you a bit more as we are getting ready for tiffin, Spark." His tone was casual, yet my eyes popped wide with sudden terror.

Electrified, with my stomach performing a nauseating turn and icy chills skittering across my shoulders, I sprang erect.

He had called me by name—and that was a name I thought buried with my five-ouncers in Jim Mullen's resin arena, eight thousand miles ago!

IT was a tribute to the arresting, magnetic qualities of those cool, half-amused gray eyes, that I did not spring upon Treleaven that second, and attempt to batter the truth out of him.

Certainly I did not fear him, did not doubt my ability to punch him to a bloody pulp in something less than a minute.

Yet I stood there, gawping like an idiot, my hands clenching and unclenching. He was obviously unarmed. He dared to call me—a wanted man—by name! Here in a jungle bungalow on Kunufunuka, refuge of the damned!

"Easy does it, Spark Starke," he went on, unperturbed, using my ring nickname and my real patronymic. "Go on and wash some of that sweat off your face. You look like the bottom of a bird-cage! By and by we'll take a dip in the lagoon, and you can get fresh linen."

"Damn you!" I said, my voice hoarser than even years of those accursed swizzles ever could have made it. "I'm not using that name. How did you come to know it?"

"I know a variety of things—everything except the one fact which might make a happy man, it seems." He smiled, but there was a veil of chill weariness which crept up over his cheekbones, making him appear ten years older than the twenty-eight at which I had unconsciously appraised him.

"Do what I say right now, Spark. You are in no danger. If I had been looking for the thousand-dollar reward, I could have cashed in on you at any time during the past weeks.

"You don't believe that? No, of course you'd find it hard to swallow in one lump; but up there on the shelf is your chamber cartridge, and the three automatic clips. You have your gun. Load up and welcome: you are getting sober now. But for the love of some dago woman, get that muck off your face!"

It was impossible not to believe him and be impressed to the point of obedience.

I washed, used a razor, brush and soap, and then drank all that remained of the tomato juice and pint of Vichy. Except for my damp underclothing and soiled whites, I was myself again.

Apparently he did not think so, for he took a suit of Kobe-made pongee, folded it over his arm, and led me to the hut in the jungle I had been occupying. Thence we went to a strip of dazzling white beach, where the water was still, and we swam for half an hour.

I am pretty fair with the old-fashioned trudgeon; but I was treated to a smooth exhibition of the crawl—the same stroke Perry McGillivray exemplified—it was rather new then—when he beat me and a few score others by a couple of city blocks through the murky waters of the Chicago River.

In a measure I was getting to respect and really like Treleaven; he seemed like the nearest approach to a genuine jigger I had met in about two years. But I had not learned ever, a tenth of the real man as yet.

WE came out on the sands. He walked away, picked up

something from a clump of mimosa, and came back. It was a

cardboard box, somewhat battered yet with its outlines and

seals intact. On the top—he grinned as he showed it

to me—was the legend:

A.C. SPALDING & BROS. NEW YORK.

A set of boxing gloves, or I was a Chinaman!

They were "pillows"—ten-ouncers, such as are used in training camps—but I damned near wept over them. I laced mine on, using my teeth on the left glove, after helping Treleaven first. Then I kicked off my sandals and capered on the hot sands, ducking, shadow boxing.

This big fellow wanted to see my stuff? Okay! I was happier than I had been in two years. I wouldn't hurt him; but in a whole lot of ways Spark Starke was himself again!

Of course I licked hum in the two rounds we scrapped, for there is a long, long distance between a really good light-heavy amateur and even a mediocre lightweight professional.

There always is. After my prelim days I had been up against a flash from Rockford called Sammy Mandell, both of us just kids then. We turned in at 120 ringside. Then there was Franklin Schaefer, 129—the gamest comeback man I ever met, Mike Dundee—137.

After that I was training, looking for a big time chance with Tex Rickard, perhaps against the king of them all—Benny Leonard. I didn't really imagine I could lick Leonard—nobody ever had—but I'd seen him in action, and coveted the chance to try.

Now on the sands of Kunufunuka, with a pair of pillows on my fists, I had my first set-to with a man vastly heavier than myself. Of course I was no longer a lightweight, I would have scaled in close to one hundred and fifty, and I had slowed up in proportion. I soon found out that fact.

Perhaps it may sound fishy, but for a full minute I was unable to hit Treleaven. He had it on me in reach; but that should not have mattered.

Scrapping with sheer joy, going through all that Jimmy DeForest, Tip O'Neill and my own ring experiences had taught, however, I finally discovered his weak spot. Every boxer has one. He couldn't hit anything but my gloves or shoulders, of course, but for a time he successfully baffled me with his guard.

Then I feinted him silly, and slammed in a right uppercut to his breastbone. It was a hard punch, and he gasped, backing away.

I stopped there, grinning. "I'll finish you next round," I promised cheerfully. "Take a minute of rest. You're a very good man with your mitts. Why don't you go in for the big purses?"

It was staccato talk—for even my wind was none too good after that hectic round. I was getting to like this big man, however; with proper training he might have been a great match against Paul Berlenbach, for instance.

The next round I slammed him plenty, and took a couple of good punches myself. Then I eased up some, just touching two or three to has belly to let him know I'd found his mark.

"THAT'S enough? You're still good," he puffed,

backing away. "When I saw you knocked kicking by Bat

Lawrence down at East Chicago—"

I caught breath in a gasp. "Good Lord, were you there?" That had been the only time I had been knocked out. And I was ashamed of it.

"Yes." He grinned over his boxing gloves, as he worked on the knots with his teeth. "You looked bad that night. I thought I could lick you easily. Of course I was counting on my weight and height to give me an advantage. But I was wrong."

"Not very much wrong, Mr. Treleaven," I told him soberly. "In about twenty minutes I can teach you how to guard your belly. Then—well, it's mostly footwork. I can teach that, too."

"Are you a good shot with a pistol?" he asked unexpectedly.

"No—rotten. I can't hit a door from twenty feet away."

Treleaven smiled. "I can hit the keyhole every time," he stated evenly. "I'll show you; and I'll trade. You teach me, and I'll teach you. Is it a go?"

I assented, but my expression must have asked much, for he grinned and motioned toward the pile of clean clothes I had brought.

"Time for a pick-me-up and tiffin at Larry's," he chuckled. "This is Friday. It'll be trepang chowder, steamed clams, baked fish with bacon strips. Wonder how Larry excuses the bacon? He's a devout Catholic—when nothing else interferes. But I rather like the old scoundrel."

At Larry's, Treleaven leaned across the table, speaking in low tones:

"First of all, Spark, I want to tell you the most important thing—to you, at any rate. You're free!"

"Some friends of yours seem to have been in strong with the Governor and the other powers that be. The indictment hanging over you has been nolle prossed, and the reward withdrawn.

"The reason why things looked so bad for you was because back then, in 1922, boxing was tolerated, but still illegal, in Illinois. The hard-shell cranks simply doted on the chance to press a murder charge; but now all that is changed. Illinois has legalized boxing. They are going to put on a heavyweight championship bout down in a new arena they've built on the lake front.

"Of course, you were not guilty of murder, and it was foolish for you to run. The Cuba Cub did die; but it was from cracking his head on the floor, not from your punch. The indictment has been quashed now, as I said.

"All right, boy, are you going back—or could I interest you in something here? I—I need a man like you."

Treleaven composedly returned to his soup, grinding into it enough black pepper to make even a Mexican sneeze.

My thoughts spiraled into a tumult I was free! I could go back to the Windy City, run a little flivver up Michigan Avenue—even sass a traffic cop if I felt that reckless! I could look up a couple of girls I'd known out in Oak Park and Austin—

But there I grimaced. Two years was a long stretch. Cecile Horton had made it pretty plain, too, that she never had considered the "manly art of modified murder" as any sort of profession for a husband.

Doubtless she had corraled a broker by now—some decent, housebroken chap with a suite of offices in the Webster Building and a couple of Cadillac sedans.

I WAS terrifically excited at first, and hurled all

sorts of hectic questions at Treleaven; but then I calmed

down. My new friend made it plain indeed that there was no

reason why I should not do exactly what I had dreamed of

doing ever since the first week of my exile. But the funny

part was that now I did not seem to care.

Sometime I should go back, of course, but why hurry? I had a small stake. If I returned to the ring I'd have to fight as a welter or a middleweight now—and in these higher-weight divisions I would be unknown; just a ham-and-beaner.

In a year or so, unless things broke really, well, I'd be out on a bench in Garfield Park, unshaved, panhandling, talking to myself.

"Tell me just why you've taken all this bother," I asked. "What good can I be to you?"

Treleaven looked me squarely in the eyes, but he took a long time about answering.

"To-morrow morning I am leaving here," he said slowly, as if weighing every syllable, "and I need a man I can trust—one who is not afraid to fight against any sort of odds. You are that man, I believe. I have looked you up—damn near wore out the Suva cable asking questions of America. I am sure of you, if once you give me your word.

"Of course you are an impulsive cuss, and might make a promise without knowing what you faced. But that isn't my way of doing business with friends. Did you ever hear of a secret agent—back in war days—called D.O.T.?"

I straightened a little. Of course my information, gleaned secondhand and late, had been naught save old tales told as mysteries, yarns passed from lip to lip among the islanders, growing to mythical proportions as they passed. I nodded, waiting breathless.

"I was that agent, Denmark Ordway Treleaven, D.O.T. No. 1113. See here."

He lifted the edge of his tan leather belt, exposing a small brass plate fastened to its underside. The plate showed the figures 1113, nothing more.

"All you'd have to do would be to repeat before last night's gang just what I've told you," he said grimly, "and I probably wouldn't see tomorrow's sun rise. That's the kind of a bond I'm offering. Do you feel you can accept?"

I started to my feet, grinning happily. This was just duck soup for me.

"Cracked down!" I told him.

But the instant my palm touched his there came a strange, ear-splitting sound—one I knew only too well, from days in France. A machine gun! I saw parts of the nipa roof thatch on the far side of the ceiling jiggle and waver, perforated—

And at that instant I grabbed a tighter hold of the hand of my new comrade and yanked him flat beside me on the floor. He understood. He yanked out a gun; but for a moment at least there was no chance to use it. The machine gun was doing all the arguing just then.

Not hurrying, especially, it dropped a yard and sewed a seam through the bamboo walls at the height of a man's waist Then it dropped six more inches and buzzed back. The lead slugs came through like angry hornets. Pieces of bamboo showered around us. We lay doggo.

"One of the gentlemen—knows me—"

Bang-bang-hang-bang!

Treleaven had sighted something through the disintegrating wall, and had fired four times, faster than a single word takes to speak.

The machine gun stopped, stuttered once, then stopped for good.

"Got them!" cried Treleaven with grim exultation. "Now, come on this way. We'll get out in the brush just to make sure. They've got plenty of men, and the guts for murder, as you have seen."

OF course, the whole Malay gang from Larry's came on the run—and, dropping out of the hidden bungalows, furtive white men sought cover, each waiting for this unexpected menace to make itself known. Even at high noon, there can be nothing much more disquieting to men with guilty consciences, than the rattle of a "typewriter."

The boom of a sixteen-inch gun from a British warship, you say? Well no. A machine gun somehow is personal; it may be looking for you in particular, not just blowing sky high some half acre of jungle brush.

The pagan war was over, though. There, partly covered by the half shell of a giant clam he had used as a chopping bowl in his domestic duties, lay Abkala, my Melanesian black boy servant. A bone-handled kris had been driven between his shoulder blades.

Over in the brush twenty feet from the bungalow, lay two other men—one a squat-browed, stubble-bearded sailor, by the look of him, and the second a patrician-featured Eurasian youth with skin the color of chocolate malted milk. On the ground beside them was that devilish, efficient weapon—a sort of overgrown automatic pistol—a Thompson submachine gun.

The sailor was stone dead. The Eurasian was grinning, in ghastly fashion, and muttering in some tongue, probably Chinese. He spat out an epithet at the first of the Malay guard to reach him.

The big native wasted not a second. His kris swung once—which was too bad, the way I saw it. Tongatabu Charley—as he had been called—might possibly have been made to talk; and when somebody starts in to spray bullets at me, I like to know what it's all about.

"As an assassination it was a damned poor attempt," said Denmark coldly, when Rotumah Larry, excited and babbling questions, came waddling up on his bandy legs. "They killed the blackboy and tried for us. Only because you can't teach a Chink or a half-caste to hold down on a target, we escaped—and got both of them."

"But—but—" bubbled Rotumah Larry, his chubby face fairly apoplectic at this menace to his extremely profitable hostelry. "What the hell's going on? Who are ye, mister? Why—"

Denmark held up one hand. A chill curved the corners of his mouth. "Just a personal matter. You may assure all your guests that they are in no danger.

"Mr. Jones and I"—Jones had been the alias I had used on Kunufunuka—"had planned to leave to-morrow morning anyway. Now, if perhaps we could take a flying proa and a pair of blackboys, we could get out about sundown to-night. D'you think you could arrange supplies and water, and have our baggage taken down?"

Rotumah Larry certainly could. Happenings of this sort were ruinous to his business, and he positively sighed with relief at the prospect of shipping us away immediately. He did not even haggle over the price Denmark suggested for the rent of the proa and purchase of the supplies. At that, of course, Larry was getting nearly forty crowns apiece from us—money paid in advance and never commuted in case a visitor found it advisable to depart in a hurry.

WE went out through the coral breakwater with

the ebb tide that evening. Two surly black-boys of

characteristic Papuan ugliness, squatted beside the bamboo

outriggers, naked save for breechclouts.

As the first breeze from behind the headland of Kunufunuka bellied out our brown, patched lateen sail, heeling us over and fairly lifting us through the light, choppy waves, all four of us shifted to port. These craft owned by Rotumah Larry were the lightest and swiftest flying-proas in the islands, craft able, in a favoring wind, to show heels to anything short of a destroyer. They were necessary to Larry, and therefore not for sale.

North by east. Over toward the sunset were the blue mounds of Kailolo and Makeete, dots of guano island long since gutted of their smelly treasure by "typical tropical tramp" skippers. Ahead was somber blue water—and what more I could not guess.

There would be a fight against odds, my companion had promised. But who was it we sought? Who had been so anxious to stop our search at its inception, as to take that foolish chance there on Kunufunuka?

Looking back, I could not feel especially frightened. Such an idiotic attempt at killing us—when they might have used throwing spears during the time we had been swimming, and defenseless, letting the sharks dispose of all evidence—did not sound like genius, or even competence. But I soon found out that Treleaven did not consider the matter a joke in any sense of the word.

He came back from the bow, exhibiting a ready pistol as he passed the two blackboys at the outrigger. They only looked at him sullenly, making no move.

"Getting so I suspect every one in the world," he commented grimly. "Everybody but you. They've got a big lead on me in this dirty business, by knowing or suspecting just who I am—while I have to blunder along in the dark.

"Sprechen Sie deutsch?" He nodded significantly at the two Papuans who watched us with unconcealed hostility.

"Not even a wenig," I grinned. "But I can parley-voo the way the mamselles taught me—kind of a lovin', one-sided vocabulary, I suppose—"

It did suffice, however, as Treleaven spoke French well enough so he could simplify. And the tale he related fairly made my hair stand on end!

THROUGH the Ellice, Gilbert and Santa Cruz

Islands—possibly much further, though nothing more

had come to light as yet—the life of a copra planter

had become the poorest sort of insurance risk.

There were hundreds of these chaps, as I well knew; men who had come to the tropics, each with "a nickel and nerve," and who had ended up by owning a dot of an island in the South Pacific, with perhaps a golden-skinned wife from the Marquesas, and living like a native prince. Probably the incomes of most of them would not have been clothes money for the same number of Sheridan Road or Fifth Avenue gold-diggers; yet many of them grew moderately rich.

Where coconut groves begin to bear in seven years, and a man can live luxuriously on something like one thousand American dollars a year, a steady five thousand a year—with maybe a lucky pearl or two—does pile up in the course of time.

I had been so anxious to get back to America that I hadn't wanted to tie down that way for any sort of money. But I had the acquaintance of lots of chaps who considered it an ideal existence.

The reason affairs were not so happy right now, and had not been for two years at least, was revealed by the trend of Treleaven's discourse.

"There is a criminal syndicate at work in these seas," he stated soberly. "You've probably heard a few things here and there—the unexplained murder of young Charnham on St. Augustine? The scapegrace son of Lord Baldeston, who came out here with a quarter million pounds—and a ticket of permanent exile from England?"

I shook my head. That chap had been over on Viti Levu several years before I stole ashore to hide at Wang Li's in Suva, and I had heard a few ancient tales of his profligate career; but what had happened to him afterward I did not know, or particularly care. His ways were not mine.

"Well, there were others," said Treleaven, carefully using the one-cylinder French I could understand. Miller of Futuna. Rice of Naouti—and poor Bill Rice had a wife and three children. Loren Lee of Pandora Bank. These and several more simply have disappeared.

"Their homes have been looted and burned—with some evidences of torture. Of course, they kept fairly large sums of money on hand; and Bill Rice was known to have in his possession at least thirty fair-sized pearls. No one, except the pirates who did him in, can even make a guess at their present value.

"Naturally, Spark, you want to know where you come in. Well, the rewards posted for positive information concerning what has happened to these planters—and, in some cases, for the arrest and conviction of the murderer or murderers—total now something over eighteen thousand pounds sterling. Every cent of that is yours if you stick with me and we get 'em!"

"But you?" I asked, looking at him searchingly. It was strange, particularly on this sort of an acquaintance; but I did not doubt his sincerity in the slightest degree. "Where do you come in?"

He was looking down at his Luger pistol, absent-mindedly snapping in and out the loaded clip. He took a long time to answer.

Finally he did look up, and I saw the genuine pain in his gray eyes. "I wonder if you could trust me—some?" he asked, this time in English. "I've got a greater stake in this than all the money in the world! Woold you care if I didn't—didn't tell you what I—I just guess—at least, until I know about it?"

I nodded. "About her, you mean," I amended, holding out my right hand.

"Yes, about her!" he stated, gripping my fist with fingers that sent electric tingles of pain to my elbow. Then a smile flashed into the edges of those gray eyes.

"I knew there was something wrong with you as a box-fighter!" he declared unexpectedly. "Now I know what it is! It's the same thing that makes me want you as a friend!"

Huh. I'm still trying to figure that out—but I'll confess it gave me what was almost the biggest thrill of my life, just the same. Treleaven had put into words just the very idea I had been vaguely struggling with in respect to himself!

WE did not go far in the proa. A little farther

on, Treleaven gave orders to shift our course and make for

Sophia Island. Now, this is a trifling seedwart in the

Ellice Islands—and only a few blacks live on it.

I wondered, but said nothing. The blackboys obviously did not like it. They protested that they had been told to take the proa to Rotumah—and I got a kick out of remembering that my erstwhile host had hailed from that latter-named island.

Treleaven was firm, however. He sat now, holding his automatic, giving terse directions which were obeyed. The waters were silvered with the light of a three-quarters moon; and even the Papuans could understand the grim, commanding menace of that Luger pistol.

"Wait here! I go up alonga house. I come back soon." Treleaven commanded the blacks, when we grounded, and the proa, outriggers lifted, was pulled part up the beach.

The blackboys grunted surlily. They glanced at one another. I was surprised when Treleaven took my arm, for I suspected one of us ought to stay and guard our provisions and my gold.

"No—just watch. I can afford anything but treachery!" said Treleaven. As soon as we were out of sight of the shore he pulled me down to hands and knees. Then the two of us hastily circled back through the bush, finding little difficulty in keeping concealed in the tangle of palmetto.

We witnessed an astonishing thing. As soon as they were sure we were out of sight, both of the blackboys leaped out of the craft we had left in their care, and sprinted up across the silvery beach. They vanished in the palmetto scrub.

I began to understand. The two boys had taken nothing that we could see—certainly not my gold, which made a good weight for any one to carry. And Treleaven half lifted me, and hurried me down.

"Hop in!" he commanded, shoving off the feather-weight proa. "Let down those outriggers—yeah. Well, Spark Starke, we're stealing the property of Mr. Rotumah Larry. That's it, let out the sail."

At that moment we slipped over the light surf, our craft as frivolous and unconcerned as the end girl in the chorus of one of Mr. Ziegfeld's Follies. And about four minutes later a dozen or so blackmen burst out from the clump of leaning palms which hid the native houses. They brandished spears. They yelled. They threw spears, but the missiles fell short.

"Well, how do you like being a popular target?" Treleaven inquired, his cool gray eyes sizing me up for what probably was the last time of our entire friendship.

I had to grin. "I've been something like a target all my life so far," I told him cheerfully, surprised to find that I was enjoying myself. "But always before I've been able to see my opponent, and anyway try to get in the first punch!"

I ASKED no questions at all concerning our destination. For that day and the next it was enough for me that I had found a comrade—and that, for the first time in over two years, I could look all men squarely in the eyes; punch them, kiss them—rather inconceivable to a jigger of my Irish ancestry—or tell them to go to hell.

I grinned at D.O.T—might as well use the initials, for he was known everywhere by them. Not in person, however! As one insignificant identity or another he went about unquestioned, or very nearly so; and many a time I heard him join in the ancient yet thrilling anecdotes of this mysterious operative, the man who had upset the Tongatabu scuttling conspiracy; who had run down the three native murderers of the British Consul-General, and then nailed the man who had employed them.

Other tales. Weird, grotesque—some of them palpably unbelievable, yet most having sprung from a germ of truth.

And here was Treleaven at my side—D.O.T. I grinned widely at the swelling on the left of his mouth, and he smiled back. He knew just what I was thinking—and it may have been his ears got just a trifle redder. I've never even thought anything about Den Treleaven I couldn't have repeated to my own mother, bless her soul in Heaven.

I was a better handler of the proa, as I showed him after a little while. He didn't have the instinct of the sea; I don't know how to phrase it better than that.

Somehow that instinct bad come to me during two years in the islands.

Though I knew no more navigation than a ham-and-beaner knows high finance of the ring, I think I could have taken that fragile proa to Honolulu—and made mighty good time. Granted good weather, of course.

Anyway, we used up that day, what was left of it. We surged in to a beach of white sand maybe ten times as wide as the sand at Wilson Avenue, Chicago, where I used to swim.

Beach? That little island wasn't anything but beach. There were a few dozen forlorn looking palms on it; and the whole island was no longer than from where the Tribune tower stands now in Chicago, down to the Auditorium; no wider than from the Congress Hotel over to the Stock Exchange on La Salle. In other words, maybe one mile by one-half, or a trifle more each way.

We camped, ate, and slept—almost before the tropical twilight had winked out. We were tired; but now we were safe for the time being; and I understood full well, from what Den had told me, that in the future lay many nights when even one hour of sleep would rest among the impossible luxuries of which men dream.

In the morning we were away again, luckily dodging a pair of puff-ball squalls which came from the northeast.

"Not much farther, Spark," said Den laconically. "There ahead is Erromango. We slide through the first break in the reef. I'll show you—"

His voice trailed off, and I knew he was thinking of what he would meet on Erromango; but I was unprepared for what he did. He stood erect, and slipped out a .45 Colt automatic, pointing its blunt muzzle in the air. One shot—a space—two more—a space—and then a final report.

HE stood gazing forward with an intentness hard to

understand, since the natives of this little group for most

part are apathetic creatures of little warlike ability.

Suddenly he muttered an exclamation of dismay.

"Look, Spark!" he cried in a louder tone, snapping in a fresh clip in the automatic.

Back there of the fern hanks and dark green scrub, a slender peeled pole rose white against the palms. A flagpole! As I watched, letting go the lateen sail so the proa's rush slowed, something red fluttered to half-mast and hung there. A second later it caught a capful of breeze from the west. I saw it plainly. A British flag—union down! Trouble, in any language!

"Make it quick, Spark!" urged Den, thoroughly aroused. "This means everything to me!"

I nodded, bringing around the proa and darting through the coral breakwater and across the stiller lagoon of the atoll, while Den stood ready to lift and lash the outriggers. For me thus far it was no more than exciting fun; but I was to find that a good proportion of my happiness in the world waited, going to waste, there beneath the inverted flag!

Just inside the screen of banyans, tree ferns, and ironwood scrub, whither we had scurried after beaching the proa, Treleaven made me drop flat and crawl. That was not so easy, as I had elected the smashing .401 Winchester as my chief weapon. Besides that I carried a ladylike .32-20 Smith & Wesson revolver in a holster under my left arm; but while this small-calibered weapon had proved itself full well in short range personal combat, it wasn't the sort of gun to train on savages coming en masse.

But with six heavy, filled clips ready for the short-barreled .401, and a cartridge in the chamber. I felt like an executioner, once I attained good cover. In this close scrub I should not shoot until I saw my man clearly—and then, of course, it would be a gamble that he did not glimpse me first and heave a spear.

Den was on the other side of the path through the palmetto, both of us on hands and knees, careful to keep the muzzles of our weapons out of the sand, when there sounded ahead a low, shuddering groan!

I froze, but stealing a glance at Den I saw him gesture forward to a turn in the path. With utmost caution we crawled forward. There, half hidden by the ferns and palmetto, lay the body of a man—a Chinaman! Hands clasped across his abdomen partially concealed the awfulness of his wound, the upward disembowelling slash of Malay kris.

Den reached him first "Watch around us, Spark!" he hurled back over his shoulder, and then bent low over the face of the dying or dead man.

"Look at me! D'you know me, Yang Chung? I am Treleaven. Who did this thing? What is wrong here on Erromango? Who did this to you?"

Under the insistent questioning, the almond eyes opened to black slits. A bubble of froth came from the pain-contorted lips, while recurrent shudders twitched the poor chap's limbs.

The bluing lips moved, though I could not catch any sound. Then, hurtled from his throat by a final spasm of agony, came a horrid awesome screech—a sound which still echoes in nightmares for me!

"Peeeenk! The P-e-e-e-e-n-k!"

Then a gobbling in his throat, a final drumming of heels upon the sand, and Yang Chung had passed on to his forefathers.

DEN threw caution to the winds. He arose, face

gray beneath the layers of tan, and deep lines cut from

beside his nostrils to the corners of his mouth. "This was

Jessie's houseboy. Come!" And he started out along the path

at a tigerish lope, ready automatic swinging horizontally

at a level with his hip.

Probably our signal, or the dying scream of the Oriental gave the alarm; for all at once it seemed that the narrow path was jammed with black men—nose-ringed savages daubed in colors, naked save for breechclouts.

A hoarse yell greeted first sight of us, and three shell-tipped spears were lifted to hurl.

I fired hurriedly; but even as I knocked over the first man the grim, detached thought came to me, "He is already dead."

With a motion not unlike a man pounding his knuckles on an oak panel, Den was firing—had got in two shots before I could unlimber and aim the .401 auto rifle.

But once in action my Winchester was as speedy as his Luger. I hit another of the black men, and he caromed side-wise like a bowling alley ten-pin. Another who came rushing got the butt of the Winchester fall in the teeth.

Then we leaped over the sprawling bodies—just in time to see a yellow devil, dressed Mandarin fashion in brocaded satin, leap out of concealment, a four-foot executioner's sword held with both hands high above his head!

The blow, aimed at me, never fell. The muzzle of my short rifle spouted fire. He went over backward, convulsively throwing the heavy sword.

As bad luck would have it, the weapon flew toward Treleaven, who saw and partially dodged. Shielding his head with his shoulder and arm, he got an ugly rip through the left armpit, one which spouted blood in twin geysers.

"Good-by, my friend!" I thought, a hard lump coming to my throat. I did not doubt that this accidental cut had severed an important artery.

But seriously wounded or not, Den Treleaven was not through as yet "Come on!" he yelled. And then—for some reason I did not immediately understand—I was hard put to follow him in a long sprint through the palm-shaded aisles, till we came suddenly upon a bamboo stockade—yes, and a gate, which opened! Den staggered and nearly fell.

A red-headed girl stepped out, glancing this way and that—then staring at us coldly over the rib of a double-barreled shotgun.

"Are you Dot Treleaven? Den Treleaven?" she demanded of me.

"I'm the guy," said my comrade before I could reply. I was half supporting him now.

The redhead let us pass. Like a pair of drunks we stumbled inside the stockade; and the redhead coolly closed and barred the narrow bamboo gate.

From then on I must confess that everything got misty, as far as I was concerned. I remember looking down with astonishment, and pulling a kris out of my right thigh. It hurt like the devil when I did it, too—though I had no recollection of being stabbed.

I saw the redhead come up, and heard her give a little cry and try to hold me as I went to the ground. Then there was another woman, taller, all in white except for a black sash around her waist—an angel, perhaps—uh—angels ought to be up on the latest styles, not 'way behind.

I fainted.

FOR a few hours it seemed that Den and I only had aggravated the trouble already heaped high upon the shoulders of Jessie Seagrue. Helped by the redhead, Jessie stanched the bleeding from Den's wound, and bound his chest tight with bandages. He did not pass out as I had, though he had far more reason.

When I drifted back to lightheaded consciousness it was to see him, clad in striped pyjamas, lounging on the cushions of a chaise longue—but with a Savage .303 rifle at his side.

Out there, behind the lattice screen of the veranda, the redhead walked slowly back and forth. She still carried that double-barreled twelve-gauge Parker; and I wondered vaguely how far it would knock her backward if she ever happened to let go both barrels at once. She looked so slender and little.

Introductions and all that sort of thing did not come in anything like proper sequence; affairs on Erromango were far too scrambled to allow even a brusque bow in the direction of the proprieties. For that reason I am going to telescope a whole lot which I did not learn till afterward.

Jessie Seagrue, the tall, calm-faced girl in white, owned this mysteriously-beset copra plantation. She was a beautiful woman, not at all pretty—and that is about the only way I can express it. Not very young; somewhere between twenty-eight and thirty-two, perhaps.

She had dark brown hair, piled high and thick in a sort of whorl on the back of her head; dark brown eyes that looked as though they had seen so much pain and suffering they could smile only wistfully; a brown complexion—one almost might have thought her Eurasian—which obviously had been given almost no benefit of cosmetics or sunshades; and the most marvelously rounded and perfect figure I have ever seen on a tall woman.

As to myself, I reversed the usual rule of undersized men for some unknown reason. All my life I have been attracted to girls under five foot five. Yet within an hour of meeting Jessie Seagrue I respected and loved her—though never in the way Den Treleaven loved her. I saw her pause a second while she was carrying me a lime swizzle, and pass her left hand over Den's curly hair.

I know I was supposed to be semiconscious and in need of stimulant at this time, but I saw that much; and I knew just why my comrade had made so much haste in landing on Erromango.

Therefore, when Jessie, the only left-handed woman I ever have known, held that tall glass to my lips, I held my breath an instant at what I saw. On the third finger of her left hand were two rings; a flat-cut solitaire diamond fully three carats in size, set in platinum, and a chased platinum wedding ring!

"You are married!" I ejaculated.

Pain came into her eyes, though her hand did not waver in the slightest. "Yes, Spark, my friend," she answered, and her full, resonant tone was like some stop I have heard on a big church organ in Oak Park.

"Don't try to talk just yet. Denmark has told me about you. He will tell you about me. Yes—can you hold it? Well, you will be all right soon. I wish we could sew up that rip in your leg, but I cleansed it thoroughly and swabbed it with mercurochrome. It will heal.

"But now—

"Patsy, come here! I'll take that scattergun for a little while. I want you to meet a chap Den says is the best man of his size in the islands! If you want to, you can hold his hand. He is too weak right now to resent it!" The half-tart sort of introduction proved how thoroughly the elder girl understood her niece and charge.

SO that is the way I really got to know

Patricia—Pat O'Hearn. The redhead. Jessie's niece, an

orphan girl of nineteen with a legacy of a couple thousand

pounds which she had come to Erromango to invest under the

guidance of Aunt Jessie Seagrue.

Of course I had glimpsed her once before, but then I was reeling and out of my mind because of the wound and the stress of deadly conflict I really had not focussed any particular attention on her. Just about one fact had registered, and that was that her hair was red.

Well, so much was correct—still is. Red and bobbed. Times I feel poetic I call it chestnut or auburn. And Pat likes it. But in the sun it's as red as any sunset you ever watched from Benton Harbor; Irish red!

I'm still trying to tell myself a little bit more and more about Pat, so you'll have to excuse me if I don't get this first meeting all straight. Pat is like no one else in the world—and she was even less like 'em just that minute!

On her spiky little French-heeled slippers—I don't know how she got around on them, even indoors—Pat stood five feet three inches in height. She was regal, even at that, slender and beautifully proportioned from snub nose to slippers. I don't believe she had a bone in her lovely body much larger than the left eyewinker of a gnat; and all the rest was electric energy expressed in its most alluring form. She—

But I'm a dub at descriptions. Just to the ladies I'll say she was wearing a skimpy, fluffy little dress of bright blue, a shade lighter than her eyes, and rolled stockings of a color called beige.

She gave over the double-barreled shotgun. "It's cocked, Jessie," she said.

Jessie smiled, looked at me searchingly, and left. I glimpsed her through the window sometime later, much later, walking back and forth. For the next few moments I saw only Patricia O'Hearn.

"Kill or cure," she said conversationally. "Spark Starke, I don't think you are bad off one bit. I'm going to have you up on your feet right away!

"Aunt Jessie and I have been waiting and hoping for a couple of men, because we're in a tight fix. Now you chaps come—and how! With Mister Pink Papa out there with all his niggers, d'you think we can let you lie around and absorb mercurochrome? Not by a damsite! So this is my first step in the cure."

I give you my honest word, and you can believe it or not She came over to me, sat on the side of my cot, swiftly put one of her soft, strong arms around my neck, and kissed me full on the lips!

Then she went back smiling, just as I was reaching up to hold her.

"Kill or cure, I said!" she laughed—but I saw that color had crept up into her cheeks. "Revive now, Mister Starke—or I'll double that dose of medicine!"

On a real inspiration I did my best to faint—though that was impossible, with my heart suddenly pounding out a feverish one-twenty to the minute. My eyes rolled back as far as I could roll them. I tried to shudder like I was dying.

Probably I gave a mighty poor imitation, for Pat just drew farther away, laughing. "Now you may hold my hand," she tantalized. "I think you will recover!"

I WOULD never have forgiven myself for as much

as entertaining a notion of cashing in from that moment

forward! There wasn't a speck of danger, though. I didn't

even rate another dose of the medicine which had given me

such a sudden, tremendous interest in speedy recovery.

As a matter of fact Den was much worse off than I, weak and pretty nearly bloodless. My muscle wound healed swiftly. Next day I was up, bandaged tightly, and able to spell the girls on the watch they kept.

Den took a glass of palm-wine arrack—villainous stuff much like the white mule of the States—and insisted on resting there on the veranda, a ready rifle at his side. His left elbow was strapped down to his breast, but he had a certain freedom of movement from the elbow down to the fingers.

Den told me what he knew of the situation on the island, the first time the girls both slept.

"If you see a big, fat-stomached, albino Greek anywhere around here, knock him down, truss him, cut off his nose and ears if you wish—but don't kill him!" was his surprising opening.

"He is a giant in strength, I understand; I've never set eyes on him—though I mean to," grimly. "He is the worst man in the islands, Spark. I told you I thought a criminal syndicate was operating, killing off planters, torturing them for their little hoards of wealth, killing them then? Well, from what Jessie says, I think we'll have to revise that estimate some.

"This giant Greek has almost white hair, she says. His eyes are blood red in the sunlight. He has no eyebrows, no beard. He wears no clothing from the waist upward; but his skin does not brown. There is no pigmentation in it. He is pink always, and gets redder when he is heated by sun or in combat, like a lobster in boiling water.

"The Pe-e-e-e-n-k!" I cried, shivering as I mimicked in a shocked voice the dying scream of the Chinaman my comrade had called Yang Chung.

"Yes."

"And is he here now? What does he want?" My thoughts flew to that sweet, red-haired spitfire who in less than twenty hours had enslaved me for life—and two or three eternities thrown in, if I had my way.

"I don't think he's here," said Den thoughtfully. "His men are here, though, some of them. He has taken the thirty-odd blackboys who worked for Jessie, killing her Scotch foreman and the only personal servant on whom she had learned to depend—Yang Chung. The blackboys probably have been taken to Mallikolo or some other near island, and sold on contract as laborers. There are a lot of unscrupulous planters who'd take 'em and ask no questions. Plain slave trade, of course.

"I'll look for Mister Pappas in a day or two, if Jessie is right. All I pray is that I'm ready for him when he comes!"

"And all he wants is the slave shipment—not the plantation?" I demanded, my thoughts centering around one very weary but smiling-eyed redhead whom I longed to put my arms around and comfort and reassure.

"Everything!" responded Den with terrible succinctness. "Jessie herself—her copra plantation—and what does the rest matter?"

"One redheaded part of it matters a hell of a lot to me!" I responded fervidly. "I—oh the dickens, Den Treleaven, I, I—" My voice trailed off in confusion. That was the first time in my life I ever had confessed to any one that I struggled to understand even in myself that mysterious emotion called love.

"Good leather!" he answered with slow, quiet understanding. And he did not scoff. "I'm very happy to've met you, Spark Starke—and I think some time she will be happy too!"

I DID not get a chance to ask him what had been on the tip of my tongue for minutes. Why should I not kill this albino Greek, Pappas, who was credited with all these gruesome island tragedies? Why grant him even the space of a prayer to his alien gods?

But I did not get a chance to ask Den privately; and before I saw him again the world had whirled around three times and done a backflip from the high springboard. I looked again at Pat, and started to think of a possible future for her, and myself. And in that second the most horrible thought of a checkered lifetime struck me!

Back there in the proa on the beach, lashed firmly beneath the stem strut, lay a Washburn-Crosby flour-sack in which were eight triple-sewed pokes of virgin gold—something like two hundred and forty Troy pounds of virgin gold, worth eighteen thousand English pounds sterling! I had forgotten it as completely as if it never had existed!

Perhaps a sensible man would have talked with Den Treleaven; yes, I know I really should have done so. Yet uppermost in my mind right then was the appalling thought that every cent I had in the world had been abandoned back there. It certainly would fall into the hands of our enemies, unless I myself did something about it. Probably they had discovered it even now.

May I plead a certain momentary insanity? I don't know what love does to other men; but this was the first time I had wanted a woman. And I wanted her fiercely, her only, and if I could not have her I cared nothing for myself.

Then this remembrance.

A stake good enough to start a woman and myself and a plantation home on one of these islands—and I had deserted that golden stake, two years of work and danger, without even a backward glance!

Well, that had been the Spark Starke who cared not at all for others. I realized with a feeling akin to agony that I was not the same careless, hard-boiled customer I had been. I loved a girl with all my heart, soul and body, and I was not the least ashamed to let the whole world—barring one person—know it!

Her I could not tell. Behind her easy intimacy had come the handshake of comradeship. When I wanted to say more to her than can be told in the firm hand-clasp of fellowship, I saw her drawing away, her blue eyes frosting over. I was further from her than at that first moment. It is often so, as I later learned.

"Be yourself, handsome boy!" she told me. "If we're going to die tonight, s'pose we do it up in good shape. Wake love to me some time again—but not till Aunt Jessie finds her baby!"

"Baby! Baby!" echoed aghast. "She—?"

"Sometimes I think men are damn fools—and other times I like 'em,", stated Patricia cryptically, and left me flat.

I HAVE to tell some more that I didn't learn until

later.

At the age of seventeen my hostess, Jessie Seagrue, had met a middle-aged captain on the Blue Banner Line, a passenger service plying between San Francisco, Honolulu, Apia, Suva, Singapore, and way-ports.

The captain was moody, but handsome in his uniform. He had buried two wives, neither of whom had been spotlessly true to him—as he knew. So for his third be picked a seventeen-year-old girl who wanted to see the eastern half of the world, and to whom a voyage under the Bine Banner would spell real romance.

To the captain himself, of course, this long since had become routine, drudgery. He could not even talk in Hawaiian moonlight, and any man whose tongue is silent then has lost all touch upon the beauty of youth and love.

I don't care much about the captain, but I'll hand him this much. He left every cent of his thirty-odd thousand dollars he had saved to his girl-wife. Probably his conscience troubled him a bit, nights when he lay awake.

Jessie Seagrue had used over a third of it in a vain search for him and the baby when the two vanished. The whole affair simply did not make sense, at least at first. Captain Michael Seagrue had more than a score of children—various hues—growing up in ignorance of him.

There was no reason in the world why he should have exhibited a sudden fondness for a baby son who looked so like his mother, for Jessie now for a long time had moved the veteran out of apathy only seldom. She could not be a companion for his old age, for she was not old; she was young, vital, and saddened only by her first tilt with life and love.

But she knew in her heart that both could be supremely delightful, especially love. Though she had kept it even from her cool handshake—most times—she had come to love another man. It was a secret anguish speaking poignantly only from the depth of her dark eyes.

The rest of the money Jessie Seagrue used in buying a part of an island, far from the ruined copra plantation of her husband. She thought always of her son, and a little, perhaps, of a tall, austere man with passionate eyes—Denmark Treleaven. A man who never had spoken a direct word of love to her, but who would do so—when and if!

When and if Jessie received proof that Captain Michael Seagrue was dead. All that was left of her marriage romance was loyalty, and her mother's love for a child. But that was enough. For it she would deny a far greater love. Like any mother she longed for the youngster, of course.

And that was what was wrong with my comrade.

Not quite all, however. He told me.

"That albino devil was here ten days back!" stated Den, a lift of unappeased fury in his voice; he never had even seen the man he hated.

"He said he had taken Seagrue and the boy—four years ago—and knew just where they both were now!"

THAT was all ahead of time. During most of the time

I fought for this strange cause I had only a hazy idea,

really, of what I was trying to win. Actually it made no

difference as far as I was concerned; but that a comrade of

mine could be so deadly serious about anything, suited me

immensely.

In youth and sublime ignorance, I never doubted that in the end we could find the albino Greek, rescue Captain Seagrue and the boy, and win out with my gold—and my sweetheart-to-be. Yes, I called her that frankly enough to myself, even at this ridiculously early moment.

If she had guessed, I have no doubt she would have taken a kris and lopped off both my ears. But she didn't; I kept that one foolish secret from her, even though other matters of moment fell from my lips all too often.

I gasped at Den's revelation, and pitied him. Chivalrous, stern with himself in all matters dealing with indulgence, he would not yield an inch. But I got no chance to try my poor hand at condolence. He left me brusquely; and I had a tough problem of my own to solve.

Memory of the gold had returned most poignantly. Now I knew that these others could not be bothered with such a trivial matter, but for me it was far from trivial. I had risked my life for nearly two years, locating a rich placer. I had worked the find for months, with not even a Dyak boy to shovel the sand and gravel into my sluice.

Could I leave all that stake back there in the hands of any blackboy who chanced across the proa?

I could not. Quietly I donned two bandoliers of cartridge-clips, took up the automatic rifle and my little Smith & Wesson, stuck a handful of cartridges for the latter in one of the pockets of my jacket, snapped a two-quart canteen of fresh water to my belt at the left hip, and slid out of the window.

It was an eight-foot drop to the ground, but I lit with only a dull clunk-k-k of the heavy clips. A half moon was just rising, and I could determine the direction of the sea by a few cracks of moonlight showing through the palms and breadfruit trees. On hands and knees I crawled across the cleared hundred feet which circled the bungalow.

I made the bamboo stockade, and wormed away into the palmetto scrub. No one seemed to be about; doubtless all the blackboys belonging to the albino Greek were waiting the return of their master, before disposing of these unexpected defenders of the plantation.

Cautiously I rose and took my bearings. The night made everything look strange, but I was used to jungles at night. I soon realized I had quite a space to travel, not using a trail to the water. But it had to be done. I started, holding the rifle at ready.

Something moved behind me! I froze—then started to turn with infinite caution. If now I had been discovered by the men of Pappas the Pink I was a goner for sure. But even in that tense moment there could be a lilt of comedy. Its medium was a double-barreled shotgun.

"STOP where you are!" commanded a voice that

was almost the hiss of a serpent. "If you move, I

will—"

The barrels pressed into the small of my back, but now they did not dismay me in the least. I had recognized that voice.

"Pat!" I whispered. "For the love of Pete, what are you doing? Why are you out here?"

"You're answering the questions!" she returned with some asperity. "Wounded, supposed to be helping hold the fort—what are you doing out here? And drop that gun! Are you betraying us to Pappas the Pink?" She poked the gun at me again, and it nearly smashed a floating rib.

"Oh, go to the dickens!" I said, exasperated. "If you want to listen I'll tell you. But take that damn gun away from my wishbone. You women—"

"Yes-s?" Her voice was silky; but she prodded in a little harder with the gun.

It made me desperate. "All right, listen to me, you wild redhead!" I whispered harshly.

Then I told her about the gold that was lashed in the bow of our proa, how I had got it, oh, a lot of useless things that you have to throw in for explanation any time you talk to a pretty woman.

"For the first time in my life I've honestly fallen in love!" I concluded—almost saying something, but not quite doing it. Always I have been delighted that embarrassment held my tongue just then.

If Pat had guessed she at least would have given me the go-by that second, or maybe even pulled the triggers of her buckshot gun. As it was, she listened, and even seemed to sympathize a little.

"Oh, you poor man," she said. "And was it a black girl you were bound out to visit at this hour?"

Damn! Out there in the scrub at the edge of the jungle, forgetting enemies, my dual responsibilities, everything, I sat right down and pulled her to my side. I was relieved that she did not seem to think the shotgun a necessary protection any longer.

I could not see her very well, though the scent of her hair was dominant over the jungle miasmas, and even penetrated the heavy lush odor of the night blooming cereus. But I knew Pat was there. I could touch her; touch her hand. Even that made me tremble. Her shoulder seemed to lean against mine for just an instant.

"Gold!" I told her throatily. And then went on to detail the quest, my supposed exile—oh, in twenty minutes I suppose I told her everything there was to know about me.

"And now I'm in love!" I declared again at last. "I must have that gold, so the girl I want for my wife—er—" And I bogged down in confusion. Great mumps on a moonbeam, what had I said?

BUT Pat must have been smiling—I could not

read the expression on her face. She placed a hand on my

arm.

"You're all right, Spark. I could almost wish I was your woman. But I'll help you out, boy. All the world loves a lover. C'mon!"

She arose swiftly; and I had to follow. I did not have a chance—or words—to protest, to tell her. Already I had said a trifle too much, and that was certain.

We started through the jungle. She led. She seemed to know just where the proa had been beached, for she went straight toward it—but not very far.

Black forms rose around us. Fifteen or twenty of them at the least. Spears were leveled at our breasts. The trail was closed before and behind, and the jungle at both sides was impassable.

Pat saw that we were caught. She dropped her shotgun, even before a command was voiced. The silent menace of the spears was enough to tell her the story. And she caught my arm before I could unlimber the two weapons I had.

"No use, Spark," she said in a low tone.

"No, not a damn bit o' use!" boomed a heavy voice. "Hey, Loochee, swing a tawtch. Right hyeah. Thass O.K. Yeah—"

Confronting us, looking us over as if we were a pair of bugs lately crucified for the collection of an entomologist, was the most enormous human being I had seen.

He was as tall as Jess Willard, but very much stronger and heavier. I have heard that Pappas scaled three sixty, but that is a later tale; I do not vouch for it. At any rate he towered there above me, my head reaching just to his shoulders. I did not see the rest of him clearly—and I thank my Maker I did not just at that moment.

I stood petrified. Not so Pat.

"Well, my man," she said coolly, coming up and placing her arm on my shoulders, "I've always wanted to tell a man I loved him before he got sappy and childish about me. I love you! This seems to be the end of the road. D'you want to kiss me once, Spark?"

Did I?

They knocked me on the head. But not before I had kissed her. And what else in the whole wide world could matter?

I KNEW that the back of my head received the spear butt, dazing, but not knocking me completely out. Falling against Pat, my arms about her. I carried her to the ground also. In a second, practiced blackboys had seized and bound us securely with palm fiber. Then, at a bellowed order, they stepped back. The white glare of an electric torch fell squarely into my aching eyes.

Standing on spread legs as massive as banyan trunks. Pappas the Pink stared down at us. He reached over one huge fist, on which the white hair stood out in moist unlovely tufts fully an inch in length; he caught Pat by the left shoulder and turned her face upward. Under his rough grasp her frock ripped. I felt her quiver where her bound ankles had been thrown against mine; but she did not cry out.

"A-a-a!" It was a bellowing bleat of disappointment. As if disgusted at sight of beauty he could not appreciate, he hurled her prone again and seized me by the hair.

"These are not the ones! Where did they come from, Loochee?" I was flung back as he spoke. "This D.O.T was let slip through—but t' hell with it. Take 'em out to the ship. Don't kill 'em."

Things happened so swiftly that my telling seems like the backing and scouting of a hesitant inchworm. But in the space of seconds by the light of that torch I saw our fat-bellied, giant captor in all the repulsive ugliness of his semi-nakedness.

He wore sea boots which, because of their size, certainly must have been made to order. He wore knee-length whites that looked like Kobe weave in Formosa wild silk—Yamatoya, perhaps. But they had been longer once. The bottoms had been hacked off with a clasp knife, and trailed threads of that precious fabric worth so many tiroes its weight in gold.

He wore a truly fantastic belt—a thing almost six inches in width, of shark hide, studded over its entire fifty-eight-inch length with the golden coins of all nations. Ten pounds at least it weighed.

But that one flash was all I saw. Pat and I, she calling coolly to me, "Hold up, Spark Starke!" were bundled up and taken away, out through the jungle, on the backs of blackboys, like so many bales of pearl-shell.

Pat was taken several yards ahead, and even with moonlight I could not follow her passage. Had I possessed a couple of Mills grenades right then, I should have blown up the whole entourage. The thought of her in the hands of this repulsive albino—even though he seemed to believe her no especial prize—made me seethe with helpless fury.

Sap and utter fool that I had been! What were a few paltry pounds of yellow gold, beside the virtue and loveliness of a girl who had no equal on earth, either way from the Date Line? A girl I knew I loved?

AFTER perhaps an hour's swift travel away from the

plantation, where slept Jessie and Den Treleaven unwarned

of this ill-fated defection on the part of myself and Pat,

we reached the two una boats, used as lighters to cross

these coral shoals where a sailing vessel, even one with

auxiliary motor, did not dare to chance the eggshell of its

hull.

The moon had faded behind some streamers of translucent cloud, and the starshine of the Southern Cross was no more than a faint lambence above the western nadir. Not a breath of air stirred. For that reason the single masts of the una boats remained unbent with sails, and the blackboys swung their paddles.

Still dizzied, and with a strange ache in my eyes, as well as my heart, I saw Pat bundled into the stern of one tiny craft, and leave. A tall, angular man I guessed to be the fellow called Loochee who had swung the "tawtch," stood erect He commanded the paddlers for all the world like the coxswain of a racing shell:

"Ho—hai! Ho—hai! Ho—hai!"

I was fated to go in the other boat, which was slower in departing. Pappas the Pink superintended the loading of some heavy objects the nature of which I did not discover until one of them was dropped, almost knocking out the bottom of the boat.

Then I knew. These were triple-sewed canvas pokes; the yellow gold I had sluiced from the roily Rakahanga River!

It had lost importance, however, become a factor of little or no value in my bitter thoughts. Why had I been so foolish, staking everything the whole bright world could offer—one dearer than myself to me, just for money? I was thrown roughly into an inch or two of water in the bottom of the boat. Out there the other lighter was going. I lifted my head, pushing it up against the bare, greasy leg of a blackboy.

"Till death, Pat!" I shouted after the departing una boat.

Faint but unwavering came back her answer:

"Carry on, Spark Starke!"

The marvelous courage God gives the redheads!

THROUGH the still lagoon plugged I along our

lumbering una boat, a shallow draft catboat no more like

the graceful proas I was accustomed to than a bloated baby

shark is like a needle-fish.

"Ho—hai! Ho—hai! Ho—hai!"

Like a dead white, giant Buddha, the albino stood in the stern. His rumbling voice, so coarse and low in pitch that its throbbings of vibration were almost as apparent as the silly, artificial tremolos of a tenor, growled out the strokes.

My bound wrists ached fiercely as I strained at the fiber rope. It did not give. Tears started from my eyes. If only I could free myself for one whole second, get off these constrictions from my ankles and wrists, I would leap up and swing one haymaker, aiming at that fat belly, and the solar plexus hidden somewhere behind it, inches deep.

That would knock him overboard. Then I'd leap after him—and I knew these waters well enough to realize that within one minute the white-pointers, tigers and gray nurses would be enjoying a toothsome feast.

Vain hope. I had been bound by experts in the dirtiest trade, or double trade, the world has known: piracy-slavery.

Out there lay a ship, riding at anchor without a light showing. I did not see her for a long time; but by and by there came to my nostrils a strange, hideous stench. I could not place it. The blackboys of Pappas all were Gilbert or Ellice Islanders—big, magnificent animals who were in and out of the water constantly. I was immune to their bodily odors, which never were especially offensive save on a long overland march.

And that ship with opened hatches, empty of all cargo, riding at the screened anchorage with only a smallpox-pitted Shensi Chinaman and two drunken blackboys aboard, smelled so horribly that I noticed it while we were yet a half mile distant!

Slavery! Or, as it was called in the islands then, "contract native labor." A diabolical merchandising still carried on to some extent to-day, one more profitable than guano, bÍche-de-mer, Pearl shell, copra or even pearl poaching.

But at last we were aboard, in the midst of the stench. Except for my stomach-sickness I should probably have admired the spotless decks and trim lines of the ship.

She was a three-master, square-rigged. What rotting flesh slopped about in the bilge of her hold, what shrieks of dying niggers mingled with the squeaks of rats, mattered nothing to Pappas the Pink. But on cruises he had always an excess of sub-ordinary labor, and used it shrewdly. The Dutch-built Hans Brinker, like a painted harlot with dirtied silks beneath her Sydney-Paris gown, was handsomer above than a Cunarder in her teak, oak and shiny nickeled fittings.

I am no sailor, though I have learned a little of small boats. This two-hundred-and-twelve-footer, an immense craft for these waters, is beyond me. I still look on companionways—as I believe they are called—as stairs. I hardly know a ratline from a rat. So, if I err in telling of these few but tumultuous hours, I ask condescending tolerance from sailor men.

The Hans Brinker had a motor auxiliary installation, never used. I believe that Pappas the Pink knew little of engines or motors, and distrusted them. Or it might have been the fact that there were no convenient oil stations in the waters where his dubious activities took him. I never learned. At any rate, dawn was coming. The moon had set.

THE reason that I learned about the engine was my

one stroke of genuine luck—but I'll wait a moment

to tell of it. Pat had been bundled aboard and tossed

carelessly against the removed cover of No. 3 hatch.

When I was being brought up to be thrown beside her, I saw a strange thing happen. For some reason the rope had been cut from her ankles. A spare, still youthful Chinaman I knew to be Loochee, was bending over, thrusting a brocaded silk pillow behind her tousled auburn head.

Just as I got there, carried by two blackboys, a little sick from the blow on the head and the stench left for always by that awful business in the hold, Pat went into action. She still wore rolled stockings, and slippers which had lost both their three-inch wooden heels.

Her hands still lashed, she threw herself aside. Then she launched a kick with her right foot—and believe me, Benny Leonard never swatted a ham contender any harder!

Her instep and heel took Loochee squarely just under the left ear, and the Chinaman crumpled, moaning and spitting out saliva as he tried to prop himself on hands and knees to stave off oblivion.

Pappas, who had been salting down my gold somewhere, came along then with his elephantine, thumping stride. It was getting light in the east. He was smoking a long, ineffective appearing cheroot made in Wheeling, West Virginia, back in the States.

"What t' hell—hey, douse a bucket on this seedwart here!" He commanded his personal blackboy, and kicked Loochee, not gently. The Chinaman stirred. He seemed about to awaken, but he got the bucket of sea water just the same.

Loochee struggled up, sputtering and almost strangling. But he was a Manchu by birth and early training, and knew the civilities. He braced himself and bowed.

"A slight accident," he said, rapidly gaining control of that poise and tranquillity which is the caste mark of blood in the three most civilized provinces of China.

"It is nothing, most sacred master. I have fulfilled your resplendent and honored request. I would ask one favor, though, from your munificence. It has come to my humble knowledge that you do not desire this woman, or even this man we have taken captive.

"For ten strings of cash—five given for each of the honorable captives, will you let me have them for my own? I fancy the woman, though she is of white skin. Never have I seen hair of this color, or skin so pallid."

"Hold on, Loochee. I'll have to think that over," said Pappas in his rumbling, reflective tone. For the first time I really credited him with some reasoning power, and I prayed that it would hold sway.

For the fact that he obviously looked on Pat, not as the prettiest and most delicious bit of feminity ever invented by a really Divine Creator, but as just a sort of chattel, gave me a shred of hope. If he had fancied her and taken her for himself—well, let's not talk about that!

"No, Loochee, you'll have to wait. I think these youngster interlopers are just what I need. In bargaining. You go for'rd—and stay for'rd!"

With one last, bleak glance at the bared knees of Patricia, the Chinaman obeyed. But I knew with a sickening heart that this was not the end for him; nor even for Pappas the Ogre, who looked on this slip of a girl as something beneath his personal desires.

Damn him! I still hate him for that. The stage, the movies, and all the parades of beauties on Fifth Avenue, at Atlantic City, at Deauville, oh, hell, anywhere, cannot match Pat in my estimation. But one gross animal thought her of no interest whatsoever.

I haven't any particular belief in hell; but if in the hereafter I get a chance to thrust a three-tined fork into the fatty layers of one big beast I know, believe me the job will be done to Persephone's taste!

IT was dawn. In the papers and magazines back home they used to make fun of the movies for captioning "Came the Dawn of a New Day!" But it is just like that in the low latitudes. No long, gray, reverse English twilight. It is blue-black, cool one minute. Then the sun comes up, a ball of molten orange, and it is hot again.

Though we did not know until afterward, affairs back at the copra plantation had been most hectic. Believing me on guard. Den Treleaven had not awakened for his watch at the appointed time.

It was not until about an hour before sunrise, when the blackboy besiegers left by Pappas had just convinced themselves that there was no risk in climbing the bamboo barricade, that Den awakened.

At that it was sheer luck. One of the blackboys slipped and skewered himself on a sharpened point of bamboo. His screeching howl of pain and surprise would have awakened a mummy.

Den sprang up, rifle in hand, and gazed blinkingly through the lattice of the veranda. Out there the howling continued. Four dark shapes appeared: one running silently toward the house, the other three perched atop the bamboo, two of them vainly trying to help their luckless companion.

Crack!

Den's Winchester spoke. The flitting shadow tumbled headlong, squealing and threshing like a disemboweled pig. Then suddenly it lay silent.

Crack! Crack! Crack! Crack!

The voice of the .401, sending soft-nosed bullets into those dark blurs atop the bamboo. Two of them fell. One remained, crucified but dead.

Then the click of a fresh clip, the levering in of a cartridge—and Jessie was beside the man she loved, her striped silk pyjamas identical in pattern with those she had loaned Treleaven.