RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

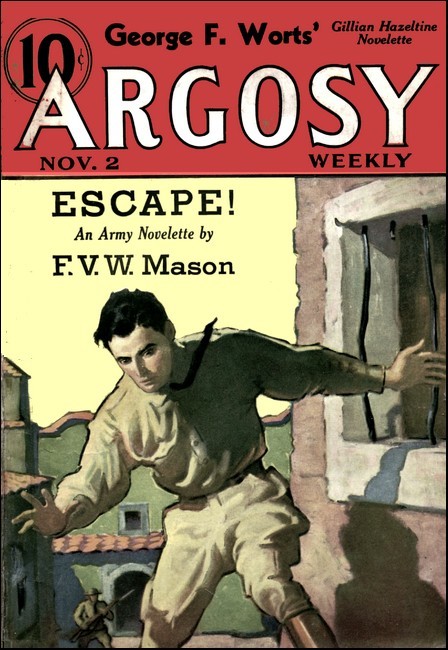

Argosy Weekly, 2 November 1935, with "Leader of the Kloomp"

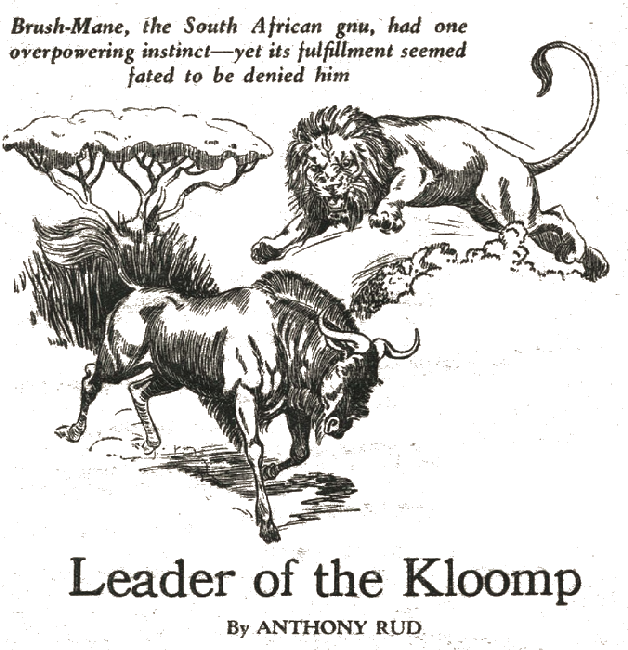

The lion's paws were extended for the killing.

Brush-Mane, the South African gnu, had one overpowering instinct—yet its fulfillment seemed fated to be denied him.

BRUSH-MANE'S mother and father were slain on the mud bank of the Malopo River, which is the nearest dependable water to the terrible Kalahari Desert of South Africa.

Kaffirs did that useless slaying. They killed eleven of those magnificent "horses with horns," more than half the adults in that band of white-tailed gnus. (Such a band, with the zebras who use it for protection, is called a kloomp.)

Kaffirs had no business with rifles, of course. However, they had them and used them from ambush. And all they wanted of the slain gnus were their cream-colored, ground-sweeping tails! These tails were greatly prized as chowries, or brushes with which to chase flies!

Brush-Mane was wobbly on his antelope legs, weak and hungry, when the Boer-Dutchman, Van Geldrop, found him and put him in the back of his wagon. At the end of that creaking journey behind oxen, there was milk for the baby gnu—cow's milk from a bottle which the youngest Van Geldrop had just outgrown.

That was splendid. Brush-Mane lived and prospered, learning in a week to graze with the cattle, and to go right to the source for his ration of milk. The cow did not object, even when this ungainly foster-child had to kneel down and turn his head sidewise.

Brush-Mane was a wild animal, however, and taming him was not satisfactory. The herd instinct kept him with the cattle nearly a year, but he fled whenever human beings made overtures.

The gnu grew to be fifty-four inches high at the shoulder, and looking very much like a moderate-sized horse—as far as his body was concerned. The rest of him, his strange head and neck, and his slender, beautifully turned antelope legs, and even the long, creamy-white tail, were grotesquely unlike any horse that ever lived.

His head bore a close resemblance to that of the American bison, but was decorated with two beards. One of these grew downward from his chin and neck. The other beard bristled upward, beginning just above his flaring nostrils and rising to the line of his eyes.

From beside his rather long oval ears two sharp horns grew straight forward a distance of six inches. A little later they would curve sharply upward, becoming dangerous and effective weapons. Even lions would lash their tails angrily and take thought, when presented with the lowered heads and sharp horns of a massed square of adult gnus—in the center of which a half dozen helpless little zebras were sure to be hiding.

Brush-Mane had a longer neck than a bison, and on the arched back of it was the cream-white, brown-tipped mane. This stood stiffly erect, eight inches high, and looked just as though it had been carefully roached by a man with electric clippers.

Down between his forelegs thick hair grew a foot long; so when viewed from the front, the gnu appeared deceptively stocky and short-legged. After a long discussion, however, scientists have decided that he belongs to the wildebeeste (African antelope) family. And he runs at a terrific pace which he can keep up for hours.

The unsentimental Boer-Dutchman, Van Geldrop, looked upon Brush-Mane just as he looked upon his young steers. As a fat yearling, the gnu would be splendid eating; though soon thereafter he would lose every ounce of fat on his whole body. His meat would get sinewy, tough and tasteless.

Just as though his queerly-assembled physical features were not enough distinction for any one animal, Brush-Mane had one mental quirk which is usually thought of as belonging only to bulls. He could not stand the sight of scarlet!

THAT got the young gnu into trouble now, and at

the same time probably saved his life. On the veldt

farm of the Van Geldrops there were a number of Kaffir

servants who dwelt in huts a short distance from the

main cluster of farm buildings. Across the fields

which separated these two groups of buildings came

a fat and waddly Kaffir gin and her stripling son.

The black woman was clad chiefly in a single folded

garment of crimson cotton....

Brush-Mane was beginning to paw the ground with his forefeet these days, anyway. He was getting more and more dissatisfied with the society of placid cows. Now he swung away from several of these slow-pokes, intending a swift run for exercise.

That second he stopped, his fierce eyes fairly bulging, Here was a great blob of that color he hated, coming straight in his direction.

True, it was worn by a human, and he usually ran from mankind, But now he snorted, stood his ground. His cream-colored tail lashed his brown sides. He trembled with a surge of sudden fury, pawed the turf. Then with a snorting roar he put down his head and charged the defiant scarlet dress.

Shrill screams of terror rent the air. Brush-Mane swerved as the frightened black woman tried to dodge. He struck her and she went down, still more frightened than hurt. But the gnu was not content with that. He pawed with sharp hoofs, put his head down and tried to gore with his short, sharp horns.

The woman shrieked and rolled over, trying to escape.

The black boy seized a coil of fence wire, an awkward weapon but the only thing handy, and belabored the gnu, yelling lustily for help. Then the scarlet dress got hooked, and torn from the native's body. It folded over Brush-Mane's eyes as he raised his head, blinding him and making him wild with shrinking terror.

With a whistle from his nostrils he started to run, the red cotton flapping in a streamer from his horns. In about a minute the dress fell off to the ground, but Brush-Mane kept going on across the arid veldt. Behind him the Boer-Dutch farmer came running with a gun; but Brush-Mane was far out of range by that time and bound for somewhere in Bechuanaland at fifty miles an hour!

Life immediately became a dozen times more difficult and dangerous. Brush-Mane had acquired a deep-seated hatred of cows and human beings alike, so went as far from them as he could. It is wild and desolate veldt along the Nosob River; but the gnu had to stay within a day's journey of that stream as it wound about the border of the Kalahari. There was no water at all elsewhere, and all wild life from lions to herons to crocodiles depended upon it.

His first rutting season had come, and Brush-Mane sought his own kind. He found them, too; but that was all the good it did him. Gnus, with the little zebras they protect, form closed corporations and do not admit outsiders, even of their own species, unless that one can force his way in.*

* Captain Shelby Harris, the British naturalist who made a special study of gnus and the queer protective instinct they have toward zebras, gives the following picture of this compact organization:

"...an outspanned caravan, particularly the canvas covered wagons, often made them curious In bright moonlight often a kloomp of gnus, with the zebras timidly hiding in the center of the compact square, would approach our bivouac, where the animals would stand for hours in the same position, staring wildly, lashing their dark flanks and uttering harsh sounds like the croaking of immense frogs If anyone tried to approach, the horned heads of males and females alike came down, with the same precision shown by ranks of Grenadier Guards with bayoneted rifles!"

BRUSH-MANE scented a kloomp one day, and sought

it out in a lush bottom where his sharp hoofs sank

fetlock deep. Some sixteen gnus and half a dozen

zebras were there, grazing peaceably; but at first

sight of the stranger every head came up. The old

males snorted and switched their tails. Four of them

came forward, ready to take turns at combat with this

young bull; but one was to be quite enough.

The newcomer came right toward the band of gnus, confident and a little arrogant. At the first snorting challenge offered by an old bull, he dropped his head and charged. Ah, but he was to learn a humiliating lesson; with his own horns half the weight and half the length of the horns of the old he-one, Brush-Mane was at a tremendous disadvantage.

There came that crashing impact, and a squeal of surprise and pain from Brush-Mane. He was lifted, hurled backward and sidewise to the soft ground; and two deep slashes in his neck and cheek ran red. He had not as much as scratched the old man of the kloomp, who stood there, snorting rather disgustedly while he waited for the newcomer to scramble up and continue the fight.

The other three bulls stood around, champing, snorting, and impatient to show their own abilities. But against their own kind gnus observe a code of rules, apparently. Only one fights at a time against an intruder; and even this one does not employ the sharp forefeet the way stallions do. When a combatant goes to the ground the gnu scoring the knockdown patiently waits, quite as though some referee were kneeling there, raising his arm and lowering it to mark the seconds.

Not that Brush-Mane needed many seconds. He scrambled up and charged, only to be bowled over a second time, and then a third. That was enough. He got up again, bleeding and groggy, all the arrogance knocked out of him—for this time. It was a lesson he was going to have to repeat several times this second year of his life; but for the time being he was quite satisfied. He turned tail and went from there, snorting reproach.

You could almost hear him say, "Darn it, all I wanted to do was join you!" There doubtless had been some ideas of leadership in his mind, also, but he had forgotten them. He wandered away to sulk and let his wounds heal.

To carnivora that smell of blood on the air of the river bottom was about the same thing as an invitation to ice cream and cake to human youths. A crocodile pushed his ugly snout a yard further out of the mud, and half-opened his yellow eyes. A quarter mile away a tawny yellow beast, a full grown lion, swung about and suddenly bounded In the direction of the alluring scent....

Life or death came in split-seconds then. The lion stalked upwind, and Brush-Mane was unwarned until the long yellow body suddenly arched over a low bush, paws extended for the killing stroke meant to break his back.

By sheer luck—and luck an animal of the wild must have as long as it is to live—Brush-Mane was just turning to face in the direction of that bush, else he would have been struck down and crippled before he was aware of danger. Being in luck for this time, however, he seemed to rise in the air without even taking time to tense his muscles.

At the same moment he flung himself sidewise, turning end for end in the air. When he lit again he was running—and at a sprint even the bounds of a disappointed lion could not equal. The gnu had a long strip of hair and hide torn free on his right flank, where the claws of the lion had missed the backbone. But Brush-Mane was through even with sulking now. He fairly flew into the open desert where he could be alone, one living dot in a great globe of sand and horizon and sky. Henceforth he would come warily to the river for his daily drink, and immediately depart.

HE hungered intensely now for companionship; the

herd instinct was powerful in him. Twice more during

the ensuing months, as his horn began to curve upward

and grow to full length, he attempted to break into a

kloomp.

Both tries failed, and left him with more battle scars.

But Brush-Mane was getting valuable experience, and he was growing in weight. He had attained full height months ago. Now when his horns developed to the full, as they would by the rutting season of his second year, he would cause them all plenty of trouble.

Then occurred one of those mysteries of wild life which men have never been able to solve satisfactorily; for some reason, probably because of an instinct for dependence, a small male zebra began to follow Brush-Mane. It did bite the ticks and burrs from his coat, but otherwise it was more a hindrance than a help. Even the zebra did not profit, for before long it was slain by a speeding cheetah.

Probably there was a mutual need of companionship through those lonely months; for certain it is that one week after the zebra was killed, the big gnu—he weighed nearly seven hundred pounds now—started a desperate hunt for mates. He would find them only in kloomps; but then many old males, quite like dissatisfied husbands, often broke loose from the security of the kloomps in which they had been raised, and assaulted new ones in this season of the year.

Brush-Mane searched a full week before he sighted a herd of his own kind. Then it was far out on the open veldt, fleeing at high speed across the horizon in silhouette. With a snort he flung up his white tail like a battle pennon and gave chase.

That band of gnus was not trying to outrun him, which it could not have done anyhow. It had been set upon, while drinking, and therefore disorganized. A lion and lioness had sprung from different directions at the same moment. The leader of the kloomp had gone down, valiantly charging the killers to give his mates and associates time to form their typical defensive square.

The leader died with a broken neck, so that the square never was formed. The lioness charged in, batting down zebras and gnus alike. And the other gnus were stricken by panic. They fled; and now Brush-Mane joined the winded herd.

They stopped after a little while, and Brush-Mane immediately chose himself a bull. He charged, snorting, and the bull met him—just once. Then the spirit seemed to leave the older animal and he dodged away.

A younger bull, one about Brush-Mane's age but a hundred pounds lighter, immediately took up the gage of battle. For ten minutes then, while crimson drops stained the sand, they went at it, rushing and butting. But the herd bull went down time after time. Finally he also quit, and Brush-Mane looked about him, pawing the ground and whistling defiance—and this time he sounded more like a horse than any kind of an antelope or bison.

One or two of the other bulls of the kloomp lifted their heads. But none was moved to accept the challenge. So after a minute Brush-Mane capered over to the females, strutting, and no doubt telling them what fortunate young gnus they were to have acquired such a valiant new protector.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.