RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

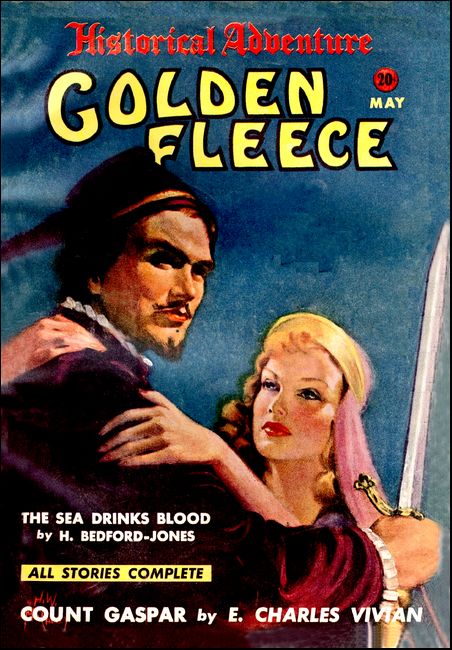

Golden Fleece, May 1939, with "Blizzard Snack"

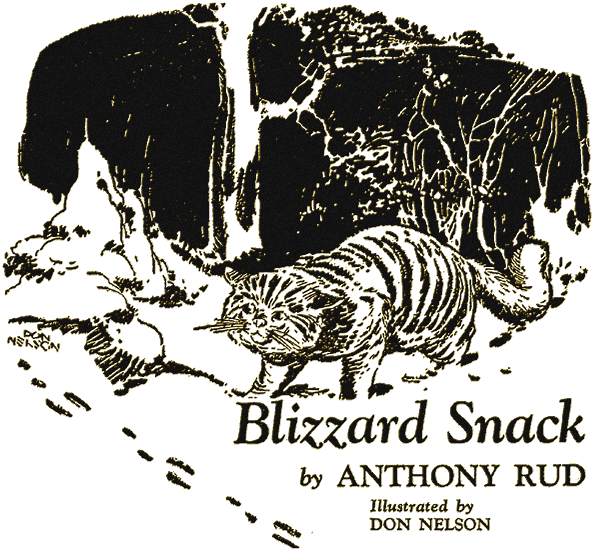

It was his fate almost always to have to prey on wild creatures larger that himself.

THE wheeling, whirling white blight of blizzard came to the Sitka spruce forests of the Skeena River on the second day of October. It poured down the slope of the Coast Range, into the long north-and-south valley of steaming hot springs and great bear fat from spawning salmon and luscious berries.

The huge bear of the region, kin to the Kodiak, sometimes do not hibernate here, in this valley between the Coast and Cascade ranges, since winter ordinarily is but a name. But sometimes real winter arrives for a short time, overpowering the lush heat which lies just a few feet underground over the whole region, and which vents in steam jets to keep the atmosphere warm and moist.

When this four-day blizzard came, the creatures of the wild were caught without the provision their kin of the Barrens always make. Except the bear, all others crept into niches in the vertical 1,000-foot cliffs, and slowly grew ravenous from hunger. The bear was ready to hibernate, and needed only this below-zero chill and stinging onslaught of icy needles, to make him drowsy. He ambled away, woofing sleepily, and was seen no more till May.

Ordinarily half of the kingdom of the wild tries to eat, while the other half tries not to be devoured. But after a blizzard all are hungry; and chances are taken for that first slavering repast, which transcend both courage and recklessness.

Spitfire was a genuine wildcat. He was two feet long, and his hairy tail added fifteen inches to that. Except for the tail, he looked like an oversized and very bad-tempered, green-eyed tomcat of some tame species gone wild.

But Spitfire's ancestors always had walked alone; and none had made the lazy compromise with man, for the privilege of sitting at his camp-fire or hearth. The tail symbolized that. It looked exactly like the tail of a tame cat that is being chased by a dog. At first glance you would have said it was impossible for a tail to swell further. But then you had not seen Spitfire in action.

This was a miniature tiger, ounce for ounce and pound for pound as ferocious as any Bengal striper that ever lived. This was a tiny tiger, born in northern British Columbia and inured to the hardships of life there, instead of the fawning easiness of the warm jungle.

Now with the blizzard finished, and a few hours of below-zero cold come upon the long, vertical valley, the demands of appetite were upon Spitfire—and upon all other wild creatures as well.

That made it hard. Spitfire totalled eleven and one-half pounds of carnivorous ferocity. But it was his fate almost always to have to prey upon wild creatures larger than himself. And this day they very well might be stalking him!

SPITFIRE left his niche of a cave, descending like a tiny

avalanche to the rubble lined shore of the skurrying Skeena.

There, almost covered by the snow, he went rigid. To his ears,

above the surr-surring of the river with its occasional wash of

breaking wave, beyond the great cathedral silence which lay above

this small monotone, through all the tremendous sugar pines and

Douglas firs and Sitka spruces of the untouched forest, had come

a far distant peal of hollow laughter!

There was no humor in that laugh. It was blood chilling. Spitfire waited, holding his breath. For another hellish, blood-curdling laugh came. Another. Downstream, around a wooded bend came eight heavy-set birds—heavier than swans, and not so long of neck.

Great northern loons! These are the biggest and most dangerous of all wildfowl in America, some old males weighing as much as seventy pounds. And all of that is fighting ferocity, plus a wisdom and an eyesight that smacks of the uncanny.

Whoo-oo-ah-h-hoo-oo! One of the leaders gave that mournful other cry of the loon, and led a way into a backwater under the overhang of a cliff. The seven smaller loons followed. They were out of sight now. Spitfire crouched and crept swiftly down the rubble in their direction.

No thought of odds. This was a possible meal—probably the toughest and fishiest meal in the world, but food. And the wildcat was ravenous.

Spitfire stalked a squadron of loons. He did not know and did not care that Cree Indians and eager white men with telescope rifles often tried their best to bag a loon—only to see the quarry duck and go below the surface, apparently dodging the invisible bullet, long before the sound of the shot could have reached it.

Loons in the water have been shot.

Usually they have been killed by a man with a shotgun, waiting for them to come around a bend in the river, or around a point in a lake. A man in ambush can kill a loon. A man in a canoe never can.

Almost tunneling, Spitfire made for the sheer drop of three yards, below which the loons were resting, occasionally letting go their whickering awesomeness of laugh—in which there is no mirth, only a ghastly cacophony of sadness, if one is close enough to hear the laugh without the echoes.

Suddenly there came a whish-thud back of the wildcat. Spitfire dropped flat, almost out of sight. Lolloping along the snowbank came a gray-white shape. A snowshoe rabbit, not yet quite camouflaged in his winter outfit of white.

Spitfire tensed, then relaxed. The rabbit was pursued. Out of nowhere behind flashed a long, thin, black shape. It caught the agonized bunny in mid-leap. There was an instant or two of snarling and ferocity, a single high-pitched squeak from the rabbit—and then the glutton, the wolverine, sank out of sight in the snow as he settled down to drink blood and break his blizzard fast on the choicest tidbits of rabbit.

Spitfire's eyes slitted. The wolverine would not eat all. There would be the tougher parts left, if he cared to wait, then go back and scavenge. But with a flick of tail, Spitfire turned his green gaze the other way. A wolverine, though weighing less, was the one animal in all the wild he hesitated to face. It would be a tough battle if the little black killer was still there. Not worth it. Anyhow, a wildcat almost never eats the kill of another animal. Nothing but real starvation would make him do so. Spitfire was hungry, but not quite that far along the road to starvation.

HE HAD tunneled no more than a dozen more yards, when a tumult

arose behind him and above. Up there was a sort of broad ledge,

with a crack which might have been a cave or a passage to some

ramp that led to the top of the cliff.

Suddenly, anyhow, six dripping muzzles appeared there at the rim. Wolves! And down from the rim, barely escaping them, beating heavy wings that needed thirty yards to raise the body in flight, came a woodcock, a capercaillie. It skidded down, throwing red-bronze feathers. It struck, and then Spitfire was upon it, biting, clawing, trying to subdue its struggles.

Wah-eee! The high whine of ferocity struck terror into Spitfire, before even he felt the claws. Then he, the woodcock—and a heavier, striped fury—went over and over in a snarling fight that lasted two long seconds.

Then Spitfire smelled his superior officer, and crouched, surrendering. The snarling fight ended a few yards away. A hungry Canadian lynx, four times the weight of Spitfire, wolfed down the bird he had killed, feathers and all.

He turned and glared at Spitfire, but did not attack. Perhaps his appetite was sated for the moment. Perhaps he did not like to eat small cats, except in extremity. Anyhow, he left. And for five full minutes there was no sound there on the bank of the Skeena.

Then a loon laughed. Nothing scares a loon. The squadron probably had heard everything, but just had listened—and then laughed. They were still there, within twenty-five yards!

Spitfire went ahead with his stalking of the loons. But now the loons were laughing among themselves, and Spitfire was not the only hungry stalker. Two more wildcats were converging upon this backwater of the stream, where nine feet below the rubble of beach a squadron of arrogant, tough but toothsome birds had come—perhaps to talk over loon scandals, preen their feathers, and tell each other how inferior the steelhead salmon of the Skeena were to the spawning army of yesteryear.

Now a hungry red fox joined the stalk. Spitfire saw him, and snarled silently. Spitfire could chase the fox easily, but he was a disturber. No finesse. He probably would let his rank smell drift down into the nostrils of the loons, and send them scooting.

Spitfire wasted no time—but a watcher who did not know all the technique would have thought him dreadfully slow. But in twenty more minutes he was crouching in the snow and brush almost above the waterline of the eddy in which the loons swam. Trod water would be a better term, since they moved their feet slowly, and meanwhile smoothed their feathers with the long, gray-yellow bills.

On the other side of the Skeena, human beings were building a railway line through to Prince Rupert, on the coast.

In this year of 1911 there were no trains running, but just at this tense moment in Spitfire's life, there came a handcar along the rusty strips of steel, with two men working at the transverse lever.

All the wild waited as though blizzard frozen, until the handcar snailed its way around a bend, and was gone.

NOW two more wildcats beside Spitfire were watching the loons.

The fox had come close, smelled cat, whined softly, then circled

upstream to jump down to the rubble below, and start a new stalk.

A beady-eyed mink also watched, from below at the other side.

The fox brought matters to a climax. Down there at water level, he found no concealment. So, foxlike, he attempted none. Quite as though he had an errand down the river bank, one which was of such importance that a loon more or less could not affect it, he trotted straight down the rubble shore, not even seeming to look at the octette of great birds there in the eddy.

The fox brought matters to a climax.

Of course his oblique eyes watched them hungrily. He really could not have much hope, but anything is a chance after a four-day fast. He foxtrotted daintily down, and almost even with his giant quarries....

OINK! observed the huge loon leader, pointedly. He sounded almost like a great hog in that moment. All his flock turned heads and looked at the seemingly indifferent fox, trotting down so very close to them all.

The loons did not think of flight. Their necks turned and stretched toward the small red marauder. Just let him start something, they all seemed to say. Just let him try, and see what happens!

Over beyond them, the mink saw the fox coming, and started business. He dipped below the surface and swam fast, hoping to get a loon from below, and drag it down, while all the flock's attention was riveted upon the fox. In his swim he came up just once, a mere dot of eyes and nose on the surface. Then he sank and swam fast, sure of his objective.

Spitfire saw all of this. He also saw that the two wildcats who were near him on the bank, were females. No thought of gallantry bothered Spitfire. Lovemaking is always better on a full stomach. Only females are more pragmatic. They were apt to beat his time if he didn't put on one of his very best performances. He started.

The fox chose that instant to turn, sprint and leap. The mink reached the idly paddling legs of a loon and fastened on grimly. And Spitfire gauged the distance, and leapt straight for the neck and back of a Great Northern Loon. Whether by chance or choice, he had elected to do battle with the old drake leader, a battle scarred veteran of ten northern winters.

A little late, two more wildcats sprang. One missed and splashed. The other caught claws in the back of a loon that had decided to fly.

Spitfire had a good hold, but he had the tough, armored protector of the loon squadron. He crouched and clawed, and started in earnestly to chew his way through the back of a muscle-corded neck. He wanted to reach the spine, and sever the cord....

Beset in three directions, and by no less than five hungry enemies at once, the loon squadron lost its indifference, and panicked. All the eight started to try to fly—after a first ducking had revealed the dismal truth. The water here was too shallow for such big birds.

Now, a loon in deep water might easily batter and drown a swimming man. Or a loon on land would certainly give concentrated hell to a wildcat, a fox or a mink. Beaks and heavy wings would stun and mutilate, probably kill.

However, a heavy loon in very shallow water is practically helpless. Its wings are of no use—except to batter frenziedly at the air and water, and attempt to take it into the air. It takes a full grown and unattacked loon at least one hundred feet to lift itself a yard out of the water.

With any kind of enemy hanging on, flight is impossible. All a loon can do is make for deeper water, where a foe can be drowned. And in the autumn of the year the Skeena is not a very deep river, save in certain holes. Mostly it is three or four feet deep.

THE mink won his battle—though it was not over for a

good ten minutes. Then a crimson stain, far up the shore, told

how the grip of claws and teeth had shifted, and a loon's throat

been torn out. But Spitfire neither knew nor cared about this. He

was battling the fiercest engagement of his whole life.

Somehow, rolling over and over, Spitfire lost his teeth-grip. Then the big leader loon had him. Beating his wings, he slammed into the rocks of the shore, dislodged Spitfire, and then with ten or twenty terrific strokes of his wings, he knocked the wildcat bloody and unconscious—for a space of seconds.

In those seconds the loon laughed once, raucously and derisively. Then it splashed back into the river and went to the rescue of a squadron member which was trying very hard, twenty yards out into the river, to drown a wildcat. And eventually succeeding.

The red brush of a drowned red fox floated past, but the old leader paid it no attention.

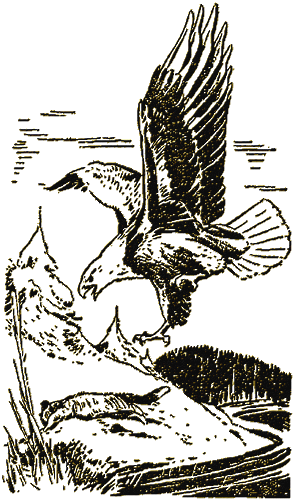

Spitfire was just stirring in the red-blotched snow, when a shadow flitted across. Then suddenly the shadow swooped. From the two-hundred-foot top of a Sitka spruce atop the highest cliff to the north, a bald eagle had seen the conflict. He had seen a body, a wildcat, lying there. He had swooped, circled once to be sure this was not some booby trap. Then the seven-foot wings had half folded, and the great eagle swooped. Wildcats and bobcats were ordinary prey, though usually the eagle liked to get them young.

A freshly dead wildcat was a treat, though. It would make up in splendid fashion for the days a blizzard had made the old bald monarch huddle in a tree, head and crooked beak hidden under his wings.

The bald eagle was starved. It swooped, and tremendous talons seized the almost limp, slightly stirring carcass of Spitfire. Then with a beating of wings, the great bird rose with its prey.

The bald eagle was starved. It swooped.

With the gouge of those cruel talons in his wounded hide, Spitfire came suddenly awake. Then he spit with horror and fright, and the fifteen-inch tail grew as big around as the swab for a field gun.

Down there on the shore a female wildcat, who had seen Spitfire and admired him, uttered a regretful "Mrr-arrh." Too bad young fellow....

But do not sign off on Spitfire just yet. Wait a moment. Something very strange is happening up there only forty feet above the river level! Of a sudden the bald eagle has gone into a flutter. He is trying to use his beak in mid-air!

Spitfire fights grimly on. He has one of the grey-yellow ankles, above the talon, in his teeth. He chews....

Suddenly a furry plummet drops. There is a splash in the shallow Skeena. Then a small head arises. Hating water, like all cats, Spitfire swims fast for the shore. He emerges. In his jaws is the foot and part of the ankle of a bald eagle. The eagle flies crazily, and finally crashes on the far shore; but Spitfire neither knows or cares.

He has crawled into the snowy brush, and is busily gnawing on the tough bit of live meat which will have to serve for his blizzard snack.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.