RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

DARREL TRENT was back in Sumala. And the beach roared under his tan shoes where the surf fell in sliding avalanches of water and spume. Darrel was regardful of his tan shoes as he stepped over the slimy reefs to get a better view of the village beyond the glittering basin of the lagoon.

Sumala was the largest island of the Felice group. Moreover, it was the richest. For fifty years it had been the paradise of adventurous schooner captains, copra kings, and shell experts. Within the shadows of the forest-clad hills lay uncounted acres of sandalwood and camphor laurels. In the eastern extremity of the island were deposits of guano that would have gladdened the heart of many a London cargo-hunter.

Coffee and tobacco nourished along the western slopes, while the plantations sang with life and the voices of contented workers. Darrel inhaled the blossom scented air with a sigh of relief and boyish delight. In the five years spent at an Australian school he had learned to look back on Sumala as the playground of his wild boyhood. In the roar of Sydney's traffic he had remembered the soft-voiced people in the palm hatched huts, who spent their lives in canoes, spearing trepang, snaring game in the hills, or culling out a tusker from the boar-herds that roamed the valleys of the interior.

So Darrel was back in Sumala, with the little trading schooner that had brought him from Port Darwin fading over the skyline. It was the unexpected death of his father that had brought him home. Old David Trent had been capsized off the reef while visiting a barquentine at anchor off Hurricane Point. It was during the fishing season, and the monster sharks were cruising in force beyond the breakers. And, for that reason, David, in his red shirt and cabbage-tree hat, never got back to his trade house on the jelly.

It was estimated that David's income from various trading concessions had verged on the princely. It had enabled him to send Darrel to Sydney, and to add half-a-dozen vessels to his already nourishing copra fleet. During Darrel's absence in Sydney old Trent had acquired a partner in his trading ventures in the person of Captain Mike Corrigan.

Mike was a relic of the Bully Hayes school of thought, when men carried the charter of slavery to the peaceful islands under the Line. Kidnapping and murdering without let or hindrance.

The islands are full of reformed buccaneers and men who sought safety under various trade-house flags. Corrigan smelt of barracoans and sweating hatches, of the silver dollars that shine for men's and women's lives. But in Sumala his past was forgotten. A new generation had sprung up, and old Dave Trent regarded Corrigan as a shrewd business-getter; a man to handle refractory chiefs or force a deal when sulking headmen were holding back the goods.

The ten-mile belt of Sumala surf sizzled and boiled in the tropic sun-glare. Across the distant taro-patches came the low, sweet voices of women at work. A small jetty thrust its barnacle nose into the gleaming welter of sapphire. Half-way down this jetty a white-roofed trade-house flaunted the Union Jack. In the doorway stood a white man dressed in sailor's serge. He was sixty and bleached to his hair roots. The bones of his lanky frame bulged under the serge. Darrel looked across the jetty and halted.

"Hullo, Corrigan," he hailed with boyish enthusiasm. "I'm coming to see you."

The breath of a hundred cyclones had blown through Corrigan's gaunt frame. Fever had grilled him until his voice sounded like the squawk of a guinea-hen. He peered under his shaking hand at Darrel Trent walking quickly down the jetty, at the tan shoes and spick-and-span clothes, until a faint gleam of recognition puckered his jaundiced face. His pale eyes narrowed to slits as though a weight of iron had suddenly descended on his monkey brow.

"Dave's kid, by the holy!" he snapped. Amazement held him stiff-jawed for a period that ached like eternity. Then, noting the broad grin on the boy's face, his manner became deadly in its slow, piercing intensity.

"What the deuce brought you here?" he demanded in a scarcely audible voice.

Darrel scanned the gaunt figure, in some amusement. Corrigan had almost passed from his memory as an interesting survival of the bad old days when men shot each other on the beaches, or burned each other's schooners at the pier-side. But he noted now that the shaking hand of the old buccaneer carried two or three gold rings that had once belonged to his father.

"I'm here because it's my home, Captain Corrigan," he said, holding out his hand. "To be quite frank," he added, with the ghost of a smile, "I found it rather inconvenient to stay in Sydney after—after my father's death. All remittances had stopped, and universities are not run on a credit system," he concluded, with a faint flush in his cheeks.

Corrigan's face had become livid. In his slit eyes burned the fires of his slumbering wrath.

"There's nothin' for you here," he broke forth, "but debts an' lawsuits your father contracted. I've enough trouble with the natives without havin' to carry a young upstart like you on my back. There's no money! it's all gone—blew away," he almost shrieked.

Darrel flinched at the words. A deep shadow crossed his eyes. His father's trade had been considered prosperous: his shipments of teak, vegetables, ivory, and oil had been the envy of neighbouring traders. If David had a business fault, it lay in his secretiveness, his almost savage passion for concealing his wealth. Long residence in the islands had made him suspicious of foreign banks and commercial agencies. Yet for Corrigan to say that David had left debts unpaid was unbelievable.

LEAVING the irate Corrigan to storm alone on the jetty, Darrel

Trent walked down a limestone path towards an ugly flat-roofed

rice-mill that hummed and clattered to the tune of a hundred

coolie voices within. Trent halted to watch a number of native

girls troop out at the sound of the midday drum. Among them was a

young white girl, slender of poise and with English rose tints in

her pretty cheeks. At sight of Darrel standing in the limestone

path she swayed slightly, checking the cry of glad surprise on

her lips.

"Darrel!"

"Mimi!"

All the dreams of Darrel's young manhood had centred upon this slim-hipped Madonna of Sumala. Among the dark, honey-skinned natives she was as piquant as a tall white flower. Yet in spite of her girlish beauty he noted a certain weariness and anxiety in her manner. "But this—this rice factory is no place for you!" he found voice to say at last. "It is the last refuge of the island coolies! It is not the hive for you, dear little bee," he told her with a forced smile.

All the dreams of Darrel's young manhood had

centred upon this slim-hipped Madonna of Sumala.

Mimi recovered herself as they walked from the precincts of the mill. After five years' separation there was much to tell. Her father, who had worked in David Trent's luggers, had disappeared only a few weeks ago. It was said he had gone on a pearling cruise to the Paumotos. Mimi was not sure. But in the meanwhile she had been forced to enter the mill as a bookkeeper to help her aunt and sister, who lived in the old Mission House across the valley.

As a boy Darrel had known Mimi's father, Bull Fleming, one of the wildest members of his father's pearling fleet. Yet in spite of his roving, turbulent nature Mimi's parent was the one honest man who had stood by David Trent in times of stress and difficulty.

Darrel felt now that his fathers trade connections were being jeopardised in Corrigan's interests. A difficult task lay ahead in discovering how matters stood. Young Trent was no fool. He had returned to Sumala to carry on in his father's name, and to extend the business beyond anything yet attempted in the islands. Ambition burned in him. Yet here he found a sandy-eyed old reprobate in charge of his father's estate, bleating about debts and lawsuits! And, worse than all, here was Mimi of his dreams and hopes inhaling the miasmas of a coolie rice-mill! The thought scourged him like a whip.

AT the door of her aunt's house, Darrel left her, promising to

see her as soon as his own difficult task was accomplished.

The news of his return had spread like wildfire through the island. The son of the beloved David had come home. The shouts of welcome that greeted him from every hut and trading canoe only served to depress him. Darrel Trent was shaken to his depths. His fortune was gone. The child sweetheart had become the slave of Corrigan's mill-agents! In those remote islands it was often difficult to fight unscrupulous trade partners. Once secure in some dead man's shoes they defied God and man to shift them.

Each moment revealed the position with greater clearness. A man-eagle named Corrigan was squatting inside his father's trade-house, collecting copra and oil from the natives, shipping coffee and sandalwood to the four corners of the earth, and receiving gold and silver for his own credit.

From the doorway of a filthy hovel on his right a tattered shape, emerged and beckoned him silently. It was Huo, the witch doctor, who preserved his ancient customs in spite of missioners and their doctrines. The face of Huo was so old that it had become white and bloodless as the reefs of Sumala. Around the loose skin of his throat was a string of shark's teeth, with an assortment of dried thumbs clustered within the arc of the necklace.

Darrel followed him into the hut. The black foulness of the interior blotted out everything except the sting and grip of cooking fumes. Huo squatted on the floor after his first salutation in fluent Sumalan. In his day the witch doctor had been of service to the dead David, helping to govern and control the natives by his crude appeals to their superstitious terrors. In return David had rewarded him with food and favours.

"Listen, son of my friend." he began from the blackness of the floor. "Too long hast thou been away from thy inheritance. Corrigan is like the green octopus, tua—he gets and keeps. I heard that he threatened thee a little while ago about the money he could not find.

"Where is it?" Darrel demanded frankly, for he was thinking of Mimi, her tired face, and the mill gates she must enter until old age gripped her. "Who took the money, Huo?"

The witch doctor chewed betel for a heart-breathing space. Then his voice rasped on Darrel with its bitter message of cunning and hate.

"Thy father feared Corrigan, who is a born man-killer and robber. But in thy absence this man-killer worked his own will in the trade-house. And thy father had grown old and foolish, as men do in these islands, he became a child again, and talked to me of thee and the gold he had saved and hidden for thy use when thou should'st return to Sumala.

"Aie! There was much money. But thy father began to hide it in pots and cooking vessels. Everyday his servants discovered his fresh hiding-places. To dig and bury money is foolish. But thy father had lost many thousands of gold dollars in the Chinese banks of Sumatra and Saigon, and thou hast not forgotten the bank of the German papalagi that swallowed his money as the sharks swallow a little child. Thy father would have no more banks.

"But here was Corrigan and his coolies smelling the air like dogs. Gold was like blood to them. And thy father was an old man with shuffling feet. His memory had gone.

"Yet thy father saw that his gold would run like water from the pots unless he found safety for his metal. Poi ana! There, was much yellow money stored in those clay jars; gold yen and taels from the compradore banks, gold dollar and English money by the hundred hundred.

"What could thy father do with so much gold? He was thinking of thee in far Syadnee at school. He desired that thy days should be free from hunger and sickness. Yellow money was the true medicine for pains and hunger, said thy father.

"But where could he hide the yellow pieces to save thee from misery on thy return to Sumala?"

A savage silence fell within the stifling darkness of the witch doctor's abode. Darrel stirred uneasily, while outside the surf thundered and beat over the reefs and channels.

"I spoke to thy father of the danger of hiding money in his compounds," the witch doctor went, on. "For was not Corrigan and his coolies searching day and night for hidden pieces of money? The fortune that was to be thine, O Darrel, was melting in the fiery fingers of the man-killer. Each day he came upon a hoard of thy father's wealth, each month he changed the gold into paper and sent it over the great water.

"That was to be the end of thy father's savings, O Darrel. This murder-man had come to Sumala a beggar, a white coolie without a loin-cloth. And my people watched him grow in authority in thy father's business. For years we have watched him swallow the profits and eat the cake! In a little while, O Darrel, all thy father's schooners and lagoons of pearl would pass to this man. Aie! Have I not seen it again and again among these white traders?

"It was the day that Corrigan found the stew pan full of gold yen, under the ashes of the compound fire, that thy father woke from his foolish dreams and fancies. There was a way to hide money, he said, that would defy the meddling fingers of Corrigan and his coolies.

"So he called to his side the Bull Fleming, father of the beautiful Mimi who liveth in the Mission House. Fleming is like the hill buffalo. His hair groweth in his eyes, but his heart is strong and his eyes are clean. Also his love for thy father was like a palm tree in his great body.

"Fleming came at thy father's call. They talked until long after dark, until the sun opened again over the green forest and the sea. They talked of the yellow money, and how they could keep it from the burning fingers of Corrigan. It was a long, cold talk, O Darrel, but it was full of the wisdom that comes to men driven hard by fate.

"Fleming the Bull said that gold was safe only when the hands of a strung man were over it. A live man must hold money day and night, to-day and to-morrow. To steal the gold the robbers must first kill the strong man. There was no man in Sumala who could kill Fleming the Bull. Not Corrigan, nor his jackal, Gada, who ran about smelling the ground for his master.

"They found a way with the gold money, O Darrel. It was to be strapped in belts around the body of the Bull. They sewed it in long strips of goatskin, gold yen and dollars and English money. All the pots and vessels were dug up and the money emptied into the long goat-skin sacks. They stuffed and rolled the hundred hundred yellow pieces side by side into these belts. It was thy father's hands that bound them to the Bull's great body.

"There was more gold than thy father could lift, O Darrel. But the Bull carried it with his head back, his great muscles showing nothing of the stress or weight. Fleming walked out in the dark of night when the village was asleep. He melted in the forest, where no man goeth who loveth his life.

"A great peace came upon David after he had gone, for he knew that the father of Mimi would hold the gold to his body until thou didst return to Sumala."

THE witch doctor ceased speaking as though he had come to the

end of his narrative. Darrel shifted uneasily, as one in the grip

of a tragic comedy that had passed beyond his control. His voice

quivered strangely as he spoke.

"My father was drowned in a fishing canoe, Huo? Where is Fleming now?"

The witch doctor laughed harshly. "Thy father was capsized by one of Corrigan's people. The island cried over his death. As for the Bull, he is still watching for thy return, O Darrel. It will not be long before he comes to thee."

A sudden scrambling of feet outside implied that someone had been listening to their talk and had moved away in haste. Darrel darted to the doorway in time to see the naked heels and sarong of a native disappearing in a patch of pandanus scrub adjoining the witch doctor's hut.

"Always an ear to pick up the money talk," Huo intoned with irritation. "One of Corrigan's coolies! The secret of the Bull is out now. If we are not quick, O Darrel, the fingers of the murder-man will yet empty the sacks of gold."

CORRIGAN sat in his trade-room, with his headman, Gada,

standing beside his table. The face of the ex-buccaneer was

creased in an ugly grin. His long legs were stretched under the

table in an attitude expressive of complete satisfaction. The

headman's features also betrayed something of suppressed

jubilation. His voice played like music on Corrigan's senses.

"We have been fools, papalagi. While we dug like pigs around the old puka hives for the gold, the Bull had plaited it in skins round his neck and thighs. Like harness, lord of the sea! This Fleming, the father of Mimi, sleeps in the forest with the money bound like armour about his muscles and chest. These things I heard in the doorway of Huo's house, when the son of the old master was listening to his talk."

So spoke Gada, Corrigan's lieutenant and native agent in Sumala.

The ex-buccaneer lit a cigar, while his molten brain digested every fragment of the brown man's talk. It was a long time before he spoke: then his words came in little choking gusts of laughter that seemed to shake the fever-grilled skeleton within him.

"So.... Bull and old Dave thought they'd put one over me! Fancy Bull Fleming wanderin' through the woods with all that dough hitched to his carcase. Ho, ho; it's too darned funny him dragging that metal round like a bear."

Gada waited for things to happen. He knew that behind the spasms of the while man's mirth lurked a poisonous hatred of Bull Fleming for what he had done. Corrigan sat up in his chair, his tufted chin grown suddenly stiff.

"See here, Gada, stick your mind into what I'm goin' to say. This chap Darrel will go after the money that's walkin' about the woods. He's broke, an' he's the breed that fights like blazes on an empty stomach. There's a way to bring Bull Fleming to us. Chasing him with coolies won't do it. Listen—just bring his daughter Mimi here. She's working at the mill."

Gada flinched slightly. He stared at the lanky, chin-tufted white man in surprise.

"Why Mimi?" he questioned suspiciously.

"Because when I get her I've got Bull Fleming by the nose. I'll leach him to play the goat with my partner's savings," he added with unexpected ferocity. "Get Mimi, an' before you can blink he'll hear she's in my house. Take my word, he's not far away. Get her!"

"The papalagi will kill her as a warning to—"

"Never mind what the papalagi will do!" Corrigan interrupted sharply. "I'll show you how to make this gold-bull spill the beans. Tell Mimi I've got a job for her in the silk store at fifty dollars a month. Tell her I'll allow her as much material as she likes to wear. I guess that'll make her jump."

OF course, Mimi came to the trade-house on the pier. She hated

the rice-mill, and if she must be a slave to someone she

preferred bondage among the fathoms of pretty coloured silk goods

stored within the cool, breezy rooms overlooking the water.

The morning was hot with a big surf booming along the ten-mile stretch of beach. Scarcely a breath of air moved the stiff-crested pandanus palms that slanted seaward.

Mimi passed in and out of the big store-room adjoining the one used by Corrigan. For two days she had striven to familiarise herself with the various kinds of silk and cotton trade goods strewn about the tables and floors. The merchandise of a dozen schooners lay piled in odd corners—glass beads, gilt mirrors, children's toys, and the countless knicknacks that appeal to the native mind. As yet the lanky ex-buccaneer had not spoken to her, beyond a few casual instructions to tidy up the jumble in the big trade-room, where the chiefs' wives had dragged everything from the shelves to the floor.

"Just like pigs," he had told her with a grin.

MIMI paused occasionally in her task to watch one of the

native canoe men scattering scraps of raw meal, into the water at

the end of the pier. Within a short space the sapphire-breasted

sea had become a thrashing hell-pool of triangular fins and

snapping jaws. It seemed to Mimi that all the reef monsters of

the Pacific had rolled up to snatch the toothsome morsels flung

to them by the laughing canoe man. Everywhere these long-bodied

sharks leaped and fought in their efforts to obtain a scrap of

fresh meat. The tiny bay seemed alive with their sabre-toothed

jaws.

Corrigan appeared unexpectedly at the door of the trade-room, a half-chewed cigar between his lips. His glance went out to the raving, fin-thrashed water at the end of the pier, and then to the Madonna-faced Mimi rolling a fathom of silk into place.

"Say there, Mimi," he called out in a voice that strove to modulate itself, "tip out some of those fancy silk beach costumes. I've a buyer for most of 'em in Honolulu, where ladies do dress before goin' into the water. No buyers for bathing costumes in Sumala."

Mimi brought out several parcels of silk bathing suits and spread them on a table. Corrigan bent over them critically, while a shade of annoyance crossed his brow. "Cost me ten dollars a suit," he said, fingering one of the blue-striped costumes impatiently. "I'm thinkin' they'll run like the devil when they touch sea-water."

Mimi was silent, scarcely knowing what to suggest. She naturally preferred the trade-house to the mill, with its dust and crowds of clamorous natives herded under the galvanised iron roof. Her father's continued absence made her position difficult. In the meantime she badly wanted the position in the house of Trent and Corrigan. She wanted to please this ill-tempered, sour-voiced trader.

Corrigan eyed her furtively as he pitched the costumes across the table in disgust. "They'll stand seawater or they won't," he grumbled. "The girl who had your job here used to try these suits in the water. I buy them from a Japanese firm in Yokohama. If the colours are not fast my buyers down south get mad an' I lose business."

"I'll wash a suit in seawater," Mimi suggested. "It won't take long."

Corrigan shook his bead, "That's no test. The last girl used to try one or two herself in the water. There's a ladies' dressing-room on the pier," he suggested dourly. "And, by the same token," he added in a softened voice, "you are considered the best swimmer in Sumala. I'll have a canoe take you out to the clear water over the reef. There's no danger for a clever girl like yourself."

Mimi had watched the sharks at the pier-end, and it was certain that Corrigan had also seen them. As a swimmer she feared neither reefs, surf, nor tide rips. Once over the reef the sharks would not molest her, she thought; they were too busy fighting over the scraps at the pier end.

"All right, Mr. Corrigan I'll be ready in a few minutes."

Selecting a couple of costumes from the table. Mimi disappeared to the dressing-room at the rear of the trades-house. Corrigan called softly to the native at the end of the pier. Instantly the fellow darted to his side. Almost at the same moment the voice of Gada beat like a flail down the trade-house corridor.

"Hurry, papalagi, The Bull is coming this way! He has heard that Mimi is in your house. See, from the window. He runs, falls, and comes on. Look!"

Through the trade-room window Corrigan saw the bull-headed figure of a half-naked white man staggering blindly towards the pier. His great chest and surly brow were bent under the weight of heavy skin wrappings that bound him from waist to throat. The ex-buccaneer turned sharply to the native standing beside him and whispered hurriedly in the vernacular: "Take her far out in the canoe. Scatter bait as thou goest. The tibaukas will follow. When thou art over the reef watch for my signals. When I raise my hand throw her in, for she will not go in when the sharks gather round the canoe. Begone!"

The native vanished.

STRAIGHT to the trade-house on the pier came Bull Fleming. The

news of his daughter's presence in Corrigan's store had reached

him among the herons and black duck of the inner lagoons. Well he

knew that the ex-buccaneer had played his last card to bring him

from his hiding-place.

The man who had drowned David Trent would regard the life of Mimi as something to be gambled with or destroyed if the game stayed against him. In the bat of an eye he saw the canoe shoot from the pier steps with Mimi dressed in a blue silk bathing costume. Also, he took in the violent commotion among the shoals of hammer-head sharks below. He was certain that Corrigan had awakened the blood-lust in these tearing, rending monsters whose livid shadows were visible all along the beach front.

In the fetch of a breath he understood the game that Corrigan was playing. Few men in the South Seas knew better than Bull Fleming what would happen to Mimi if she entered the water within miles of those fleet, blood-scenting scavengers. He turned to the fast disappearing canoe, waving his arms frantically.

"Come back. Mimi! On your life don't go into the water! It's alive from reef to reef!"

The canoe passed on, with Mimi staring back helplessly in his direction. Bull Fleming controlled the black rage that held him speechless as Corrigan approached leering, chuckling audibly at the way he had outpaced the other.

"Hullo, Bull! You seem to be loaded down," he greeted the staggering, weight-burdened Fleming. In the shift of an eye he took in the rolls of minted wealth packed within the skin bandages around the sun-blackened shoulders and hips of Fleming. Bull Fleming breathed like an animal in torment as he watched the canoe double round the distant reef-points. His lips quivered strangely.

"I've brought you Trent's money, Cap'n Corrigan," he grunted, wiping the sweat drops from his brow. "Every pound an' dollar is here, just as ole Trent left it. You'll be needin' the money, Capn', for your business."

In spite of his efforts to control his overwhelming greed, the hand of the ex-buccaneer shook like an aspen as he fingered the bandages containing the bulging columns of wealth.

"I just sent Mimi out for a dip," he stated meaningly, his thumb jerking towards the distant reef-lines. "Being a hot day I thought she'd enjoy a swim."

Bull Fleming hunched his great shoulders, nodding sullenly, while his parched lips framed his reply.

"Better give that coolie the sign that Mimi is to come back. Cap'n," he articulated. "Give it now, while the money's good and sure."

Corrigan reflected an instant then, walking to the pier and beckoned for the coolie in the canoe to return at once. The signal was answered. Fleming nodded, and again wiped his brow.

"You see, Cap'n," he stated hoarsely, "I gave my word to ole Trent I'd never give the money to anyone. See? You can take it from me, though," he added with a dry grin, "and my conscience will be all right."

Corrigan guffawed loudly as he unfastened the skin bandages from Fleming's chafed shoulders.

"Sure I'll ease your conscience, Bull. Ye can whisper to your dead friend that I took the money."

Fleming watched him with a curious light burning in his eyes. "Put the belts on you," he commanded coldly, "or I might change my mind. Put them on and feel what I have suffered, day an' night in the jungle, to save my old friend's money for his son."

"Sure, sure!" the ex-buccaneer agreed in his fierce haste to humour the sulky-browed carrier of gold. "Every man dreams once in a while of gettin' away with as much as he can carry, though hell itself is on top of the pile. Give me another belt of it, Bull."

Fleming added another belt of gold and another, until the knees of Corrigan sagged and quaked under the increasing load.

"Enough, Bull." he gasped. "Too much gold is hard on old joints. Stop, stop; I'm crucified with your goodness," he protested, reeling under the load of metal that Bull had knotted and looped to his body.

"One more an' the last, Cap'n Corrigan," Fleming cried, clapping a thick sovereign filled belt around his throat. "One more to make you the richest man in the islands!"

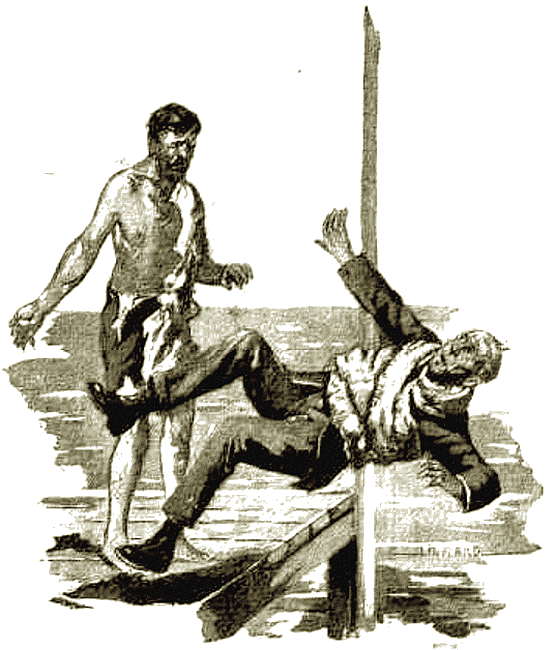

Corrigan lurched heavily and clutched blindly at Fleming to save himself from falling. He was too late. The hip of Bull seemed to touch him lightly, accidentally almost. A shout of despair broke from the ex-buccaneer: his hands clutched wildly at the flagpole at the end of the pier—and missed. His overweighted body toppled and plunged down into the water under the pier.

His overweighted body toppled and plunged

down into the water under the pier.

Bull Fleming remained rooted, staring at the swift-moving shark shoal below. In a flash the creatures had disappeared. Not a ripple disturbed the sapphire depths. Within a few short minutes the water became clear as a mirror.

The figure of Darrel Trent appeared at the end of the jetty. He came with hurried strides to where Fleming was staring into the water below.

"Where is Corrigan?" he demanded sharply.

Then his glance wandered to the glittering depths under the pier. The form of Corrigan was plainly visible, his arms outspread in a crucified altitude, like a man caught fooling with the cross of his fate. The gold had pinned him down.

"The sharks cleared off," Fleming rumbled. "He struck the water with a great noise: it scared them like a gun. But... we shall get him when the tide goes out, with all the money that burnt my flesh and bones."

Darrel Trent understood. He had gone forth from the hut of the witch doctor in search of Fleming, had searched the woods and lagoons without success.

The canoe touched the pier below. Mimi sprang up the steps with a glad cry to Darrel's side. A sense of peace and serenity was in the air. A sudden healing of drums in the village told Darrel of the goodwill of his people, for the word had flashed forth that the evil sailor man had been caught at last by the sea.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.