RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

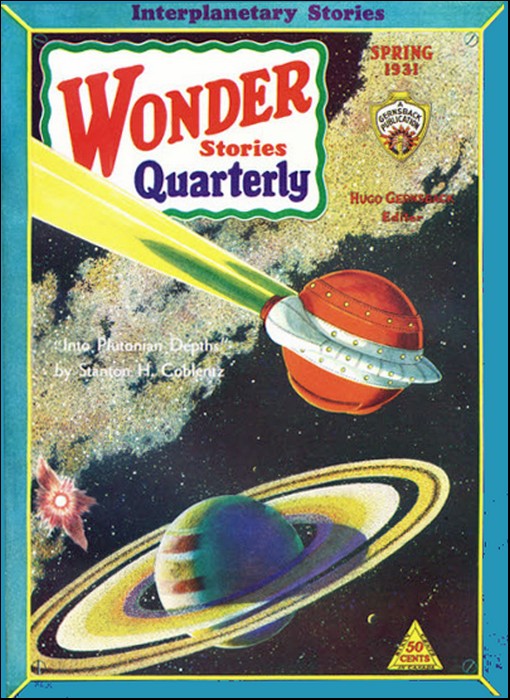

Wonder Stories Quarterly, Spring 1931,

with "The Avenging Ray"

Alec Rowley Hilliard was an American writer who worked for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission in Washington, D.C. He was born on July 7, 1908, and passed away on July 1, 1951, at the age of 42 in Alexandria, Virginia.

Originally from Ithaca, New York, Hilliard was remembered in his obituary as a dedicated professional. He was survived by his wife, Annabel Needham Hilliard, their two children—Elizabeth Janet and Edmund Needham Hilliard—as well as his mother, Esther R. Fiske, and a sister, Elizabeth Hilliard. He was laid to rest at Lake View Cemetery in Ithaca.

ONE of the most intriguing nooks in the world of science is that presented by the electromagnetic spectrum. Here we have a series of energy radiations that, as the wavelength changes, changes entirely its character and its effect on human life. We have the long radio waves that serve as an agent of man for wireless communication across thousands of miles; the same types of waves shortened become the instrument of keeping him warm across the vacuum of space that separates the sun from us. Make the waves still shorter and we get radiations that make for visible light. These long waves are all beneficial agents. But as the waves become shorter and shorter beyond visible light their character changes and they are not only beneficial if properly employed but terribly destructive if misused.

This gripping and intensely realistic story by the author of "The Green Torture" utilizes the above idea in a most thrilling manner.

PATROLMAN Pat Connolly, piloting his light car across the marshes beyond Bayside, Long Island, on his way to relieve the man in the sentry-box at the top of the hill in Douglaston, slowed suddenly; and peered ahead, slightly surprised.

At four in the morning it was not usual to see a car parked in a place like this. His surprise gave way to alarm as, coming nearer, he saw the legs. The car was drawn over to the side of the road, and out beyond the left front wheel stretched a pair of legs—motionless on the ground.

Connolly, with a final pressure on the brake pedal, came to a stop just behind the mysterious car. A "ride"—another gangster getting "his," Connolly quickly concluded. This was a regular old place for it; not a hundred yards from the spot where "Tip" Morelli had checked in a couple of weeks ago....

"A little break for Pat!" he chuckled as he climbed from his seat. "I ain't found a dead gangster for over a year!" Swinging his night-stick he approached the legs; but as he rounded the front of the car he halted, shocked. The body lay in the bright light of the headlamps—face up, and that face was distorted in a horrible expression of disgust; but it was the throat at which Connolly gazed wide-eyed. "Guy sure got it in the neck!" he muttered. Slowly he approached, and knelt down beside the sprawled figure. "Good God!" he breathed, for the man's throat was rent and torn in a way that no bullets had ever done. Blood covered his neck, and stained the ground beneath. Suddenly Connolly bent down intently, catching his breath. From the torn throat the blood was pulsing. The man still lived! The officer recognized the need for immediate action; this man must be got to a doctor. Running back to his car whose engine was still turning, he drove it up as near the body as possible.

He had just alighted, preparatory to lifting the silent figure, when suddenly, he was hit viciously by something heavy and hot and furry. The impact of the blow threw him backwards against the hood of his car.

Indignantly, Officer Connolly raised his arms to throw off the thing which was clinging to his shoulders; but, although he was a very powerful man, his efforts were futile. With sudden horror he felt a ripping of the high collar of his uniform; and he yelled, and beat the thing with his fists. A sharp pain at his throat....

With the realization that he was fighting for his life his wits returned. His right hand darted to the holster at his side; and putting the revolver against the long, heavy body of his assailant he fired three times.

In a flash the thing had gone. Dazed and shaking, Connolly raised his left hand to this throat; and took it away red and wet.

"Damn it!" he said; and then, raising his eyes, he let out another yell. The man on the ground was almost completely covered by a long, dark form! Not daring to shoot, Connolly rushed forward, and kicked at the thing with all his strength. So quickly that his eye could not follow its motions, the thing was upon him, and he was borne to the ground. Lying flat upon his back, he fired twice; and was free. Now he wasted no time.

Grasping the limp figure, he heaved it into the car; and leaped into the driver's seat. But he was not yet free. Hurtling through the open side of the car came a third assailant, and he was knocked violently over against his unconscious companion. Again the heavy weight upon him, the horrible pain in his throat....

Desperately, but with infinite care, he fired his last shot. As if by magic, the creature was gone. In second gear the car roared forward—twenty-five, thirty, thirty-five miles an hour.

"Out of it!" breathed Connolly as he shifted into high; then relief gave place to wonder—"but, what the hell—?" Getting no light on this question, his thoughts quickly returned to the man by his side. A doctor!—yes, the first thing now must be a doctor. Dr. McCord!—Right across the road from the Douglaston sentry-box; he had seen the sign hundreds of times....

At a steady rate of fifty miles an hour the car had now crossed the marshes, and was ascending the hill. Houses now and a traffic light. To hell with the traffic light! The car roared on two blocks, and came to a grinding stop. In five seconds Connolly was on the porch, ringing the bell and beating and kicking the door.

"Coming—coming—coming!" came the shout from inside, and in a moment the door was flung open. The doctor was attired in his trousers and slippers. "All right—what?" he questioned tersely.

"Man out here, snapped Connolly, "losing a quart of blood a minute. Help me get him!"

WITHOUT a word the doctor followed him to the car. Together they lifted the limp figure, and bore it into the house where they laid it upon a table. The face was a ghastly white. Swiftly the doctor worked to staunch the flow of blood. "Jugular pierced," he muttered. "Looks like a bite."

"Is a bite!" agreed Connolly. For the first time he felt weak; he swayed slightly, and sank into a chair. The doctor raised his head.

"You too?" he said in astonishment.

"Me too! But tend to him. My jugular ain't pierced, I don't think. Just groggy."

The doctor, however, walked over to examine him. "No, you're not so bad," he agreed. "I'll fix you up in a minute." Returning to the table, he worked intently, muttering occasionally. "Hospital for this fellow—die before morning without a transfusion—ought to be conscious soon, though—" As if the words had been a signal, the man's eye-lids fluttered and opened. Connolly rose, and joined the doctor at his side. His white lips moved.

"Louise?" he breathed.

A horrible suspicion came to Connolly. "Who is Louise?" he asked tensely.

The man made a visible effort. "My wife—she—"

"In the car?" Connolly barked.

"Yes!"

Headlong, the officer dashed out of the house, across the street, and flung open the door of the sentry-box.

"Moran!" he shouted.

The officer addressed got to his feet, and stretched himself. "Well, it's about time—" he started, and then caught a glimpse of the other. "What the hell—"

"Git a squad car and ambulance!" snapped Connolly.

Without a word the other scooped up a 'phone. "Squad car—number 42 box—Douglaston—snappy! Git St. James hospital—ambulance—same place! Dropping the phone, he turned to Connolly. "What the hell hit you?"

"Don't know!"

"Don't know?" gasped Moran, but the other was gone. Across the street he stumbled, and into the house.

"Fix me up, Doc; an' give me a drink. I got work to do!"

The doctor set to work. "Understand, this is only temporary. That neck of yours will have to be rather methodically sterilized as soon as possible. Here, drink this."

Connolly drank, and felt better. "Ambulance be here any minute," he said, "for that guy. Got a hunch we won't need no ambulance where I'm goin'!"

"Just where are you going?" inquired McCord with interest.

Producing his revolver, Connolly began methodically to reload it. "Down on the marshes," he said, "to find Louise, but I guess Louise is—" Catching the doctor's eye, he stopped suddenly. The man on the table, eyes wide, was staring at the ceiling.

"—is all right!" finished Connolly heartily. "Sure!"

"What is down on the marshes?" asked McCord intently.

Connolly scratched his head. "Well," he answered slowly, "I couldn't rightly say.—Some sort of—"

The harsh wail of a siren from the street stopped him. "Gotta go!" he muttered, and went—on the run.

"Well, Connolly?" greeted Captain Stecker interrogatively, as the other came into view.

"Down on the marshes, sir—a woman in a car—got to get her!"

The Captain placed his hands on his hips. "Since when, Connolly, do you need a squad to get a woman out of a car?" he inquired ominously.

"There's other things, sir—some sort of murderin' animals!"

"Murderin' animals?" repeated Stecker. Suddenly he sniffed. "Connolly, you been drinkin'!"

Officer Connolly's nerves were badly worn. He grunted angrily. "Sure—an' you'd be drinkin' too if you'd been where I been. There's a guy damn near dead now, an' there'll be a woman dead if we stand here jawin' all night!"

The other nodded. "Hop in, then," he snapped; and the car, gathering momentum, pounded down the hill. "Now what the hell do you mean by 'murdering animals'?"

"Somethin'," replied Connolly, shaking his head in a puzzled way, "that jumps on you and bites your neck."

The Captain snorted.

"'Bout the size of a dog," added Connolly.

"Pekinese or Saint Bernard?" snarled Stecker.

"No, like an Airedale—only longer and slimmer."

"Hot dog, maybe!" snapped the other. The Captain was officially in bed, and that always irritated him.

"Look!" exclaimed Connolly suddenly.

The powerful searchlight had picked out the parked car on the road ahead. And all around it dark shadows darted and swirled. At the thunderous approach of the police car, however, they melted into nothingness.

The men surrounded the lonely touring car. "Somebody in the back seat," said one. "See?"

The figure of a woman was sprawled in the tonneau—just visible. Stecker mounted the running board, and leaned inside.

"Cold!" he reported tersely. "Here, you guys—get her out."

They lifted the limp figure into the light. The skin was as blankly white as a sheet of paper. The mutilated throat told the story.

"God!" cried Stecker, "There ain't a drop of blood left in her!"

AT six o'clock that morning the man in St. James Hospital rallied enough to make a short statement, which was, in effect, this:

He, Joseph Blaine, a resident of Little Neck, was returning late with his wife from an evening on Broadway. Just beyond Bayside a front tire had blown out. His wife, very sleepy, had curled up in the back seat; he had set about repairing the damage. A few minutes later he had heard his wife scream loudly, as if in terror. At almost the same moment he had been hit heavily, and knocked flat upon the ground. His struggles to rise had been useless, as some sort of animal was on top of him biting his throat....

At this point the narrator fainted, and did not again recover consciousness. He died at a few minutes after seven before a blood transfusion could be effected.

The date was March 11.

On March 27, Frank Higgins, a real-estate dealer of Flushing, set out to play a lone round of golf on the course laid out over a section of the extensive Municipal Dumps lying between Flushing and Corona. In the early evening, he was found lying in a sand-trap, bloodless, his head almost detached.

Throughout March an ever-increasing number of complaints concerning the disappearance of dogs, cats, and other domestic animals, had been registered in the outlying districts of the Borough of Queens; and it was an astonishing fact that not one of the missing animals was ever recovered. This situation aroused considerable interest and a certain amount of indignation against the apparently inactive police.

But something more than indignation was aroused in the minds of citizens who, on the morning of April 3, were startled by the following newspaper story:

THREE CHILDREN DISAPPEAR FROM BAYSIDE PARK

Suggested Connection With

Mysterious Loss of Pets in Last Month

Three kiddies, all under ten, who, according to witnesses, were playing together in the Public Park on the eastern outskirts of Bayside could not be found at a late hour last night. The children, John Grayson—9, Amelia Grayson—5, and Robert Caldwell—7, had been sent to the park in the middle of the afternoon by their parents who live nearby. When, at six o'clock, they did not return, their worried parents set out after them; but no trace of them could be found. Police were notified, and, aided by alarmed neighbors who have been annoyed recently by the wholesale disappearance of their household pets, they instituted a search. At ten o'clock last night no results had been obtained.

Daniel Boles, a neighbor, states that about five in the afternoon, when on his way to the Bayside Yacht Club, he saw the children in the park, and spoke to them. They were playing with pebbles on the shore of the Bayside Inlet. They have not been since seen.

The police suggest a kidnapping, but the distracted parents and a number of nearby residents fear that the mysterious agency which has caused the disappearance of so many dogs, cats, etc., recently in the vicinity is responsible.

The bewilderment and uneasiness caused by this item was considerably increased by the news, in the evening papers, that the body of one of the children—John Grayson—had been discovered by a gang of searchers on the marshes, east of Bayside, "in a mutilated and bloodless condition".

The terrible similarity of this to the cases of Frank Higgins and Joseph and Louise Blaine was blazoned forth in banner headlines and front page editorials. The North Shore of Long Island was becoming alarmed.

THE seven members of the hastily-created commission sat in various attitudes about the huge mahogany table in one of the conference rooms of the Municipal Building in New York City. Their various physical positions were indicative of the varying mental attitudes of the commissioners towards the matter in hand.

Major Zorn of the State Militia and Enright Healy, head of the City Planning Bureau, leaned back in their chairs with far-away looks—frankly bored. As opposed to them, Dr. Lorian P. Jules, physicist and zoologist, listened with strained attention to the remarks of the Chairman. The attitudes of the remaining commissioners ranged between these two extremes; and the group, as a whole, did not appear to be capable of any very concerted action.

"To sum up, Gentlemen," said the Chairman, by way of concluding his remarks, "we have been delegated to estimate the importance of certain things and fatal events recently reported in the Borough of Queens, and to determine what action must be taken in the matter.

"If there is no objection, I suggest that we now hear from Officer Patrick Connolly of the Queens Police. He seems to be the only man who has encountered these—these things, and lived to tell the tale."

At these words Dr. Jules was seen to smile slightly—rather grimly; but he said nothing, and merely nodded with the rest of them. At a word from the Chairman, the attendant left the room, quickly returning, followed by Officer Connolly—very stiff and dignified in a new uniform.

Inspector Kelly, also of the Queensboro Police and a member of the commission, smiled up at him. "Connolly, these gentlemen would like to hear what happened to you on March 11. Stand at the foot of the table there, and tell us about it!"

Connolly made a good witness. He told his story in a straightforward and simple fashion, confining himself exclusively to the narration of facts. In less than ten minutes he had finished. Six of the men heard him calmly, and with little show of emotion; but with Dr. Jules it was different.

Every word appeared to cut him like a knife; as the story of the tragedy progressed his face became haggard and lined, and when the narrator told of finding the slain woman he buried his head in his hands.

As Connolly finished, Zorn, who had been gazing abstractedly out of the window, smiled unpleasantly. He had been drafted for this job much against his will. Several important personal projects had been rudely interrupted, and he was not feeling particularly friendly towards anybody or anything.

"It would appear strange," said he, "that the officer did not even so much as glance into the darkened car on his first visit to the spot. It is possible that the danger to his own person at the time might be slightly exaggerated."

Connolly went a dark red, but said nothing. Inspector Kelly gazed coldly at Zorn; then turned to the officer. "Open up your collar!" he said grimly. Connolly complied awkwardly, and in another second a gasp went round the table. Wide, livid scars zigzagged in every direction on the muscular neck.

It was Zorn's turn to flush deeply. "Sorry," he said quickly, "—damn' sorry!"

Jules raised his head. "Officer," he said, "did you notice any peculiar odor on the scene of your adventure?"

Connolly looked startled. "Why, yes sir! Now that you mention it, there was a smell something like a skunk; but I didn't connect it up with the other things. Come to think of it though, I do believe it came from the things I was fightin'."

JULES nodded. "Yes," he said slowly, "it did! Officer, would you like to know what the things were that attacked you?"

"I sure would!" grinned Connolly. The others leaned forward with sudden interest.

"They were weasels," said Jules quietly.

The others merely gaped at him. Zorn threw himself back in his chair with a snort. Utter astonishment showed on every face except that of the Chairman.

"B-But, sir—" began the officer eagerly, finding his voice, when the scientist interrupted him.

"I know what you are going to say. You would say that weasels are tiny animals which prey upon rats and chickens, and that there are no weasels large enough to attack a man."

"Which there aren't!" put in Zorn disgustedly.

Dr. Jules raised his hand wearily. "Please hear me!" he said. "The unhappy truth is that there do exist weasels of that size and vitality, and I—" he drew his hand across his forehead, "—I am responsible for their existence! I am responsible for the six ghastly deaths we know of and for all those which are to come—which must inevitably come...."

Here his voice trailed into silence. He appeared to have aged ten years in an hour. Again he buried his face in his hands.

All present gazed at him with startled looks, as if suddenly doubting his sanity—all except the Chairman, who now cleared his throat.

"I am sure," he said softly, "that Dr. Jules exaggerates his responsibility in the matter. I, at least, must share it with him. A year ago he came to me, because of my position in the Public Health Department, and warned me that there was danger from these animals of his. I must admit that it was some time before he succeeded in convincing me that the matter was in any way serious.

"The affair received very little publicity then; even the reporters would have none of it—most of them, anyway. Finally, however, I got a search going. We pretty well combed the North Shore as far out as Port Washington, but turned up nothing definite. Dr. Jules was not satisfied, but I was—and that was the end of it."

Major Zorn, in whose expressive face, incredulity and astonishment were mingled, now spoke in an awed tone. "Good Lord, it isn't possible! Why, I've hunted weasels—I know what they're like. A weasel that size would be a match for any ten men!"

Jules looked up. "You are right," he said bitterly. "They can run like the wind, stop and turn in a flash, and I have seen them make leaps of fifty feet and more. Some of their movements are so quick as to be invisible to the human eye."

Inspector Kelly whose mouth had been hanging open for the last five minutes now burst into violent speech. "But where did you see 'em—where did they come from? What the hell is this all about, anyway?"

Jules looked at the Chairman. "Dr. Matthews, my story is not long. May I tell it now—in my own way?"

"Yes," said the Chairman, "it is certainly in order now.

Jules started speaking with an obvious effort to be calm and clear. His hands were folded on the table; and he stared steadily at them, never shifting his gaze.

"Up to a time just about ten years ago," he began, "I was a member of the staff of the Zoology Department at Cornell University. I was also extremely interested in that division of physics which deals with the vibration of ether waves (the waves that, among other things, produce light and color, as you doubtless understand).

"I was particularly absorbed, naturally, in the effects which ether waves of certain frequencies of vibration—particularly the X-ray—have upon animal life. It had already been definitely established at that time (and I may say with all modesty that I was one of those who aided in the proof) that X-ray treatments have a marked effect upon the reproduction functions of animals.

"The effect is briefly this: when an animal is exposed to X-rays for a sufficient length of time, any physical peculiarities which it may have—such as size, vitality, disposition, or even deformity—will inevitably be repeated in its offspring. The fact is rather well-known by now, and will be no surprise to most of you."

His audience—including Connolly who, at a smile from the Chairman and a gesture from Kelly, had seated himself at the lower end of the table—was eagerly attentive. Several nodded their heads at this juncture.

"Immediately," continued Jules steadily, "there is opened up an extremely attractive line of activity—attractive to the scientist, at any rate. It is obviously possible, by judicious use of the X-ray treatments, to create an evolutionary process all one's own; that is, to deliberately influence the development of an animal species along pre-determined lines. All that is needed is time, patience, and—incidentally—money.

"I was immensely enthusiastic, but I lacked that last requirement. And then, suddenly, I got it! A wealthy relative died, leaving me all that he possessed."

HE paused with a faint, reminiscent smile; but as nobody spoke, he quickly continued.

"I shall not attempt to describe to you my joyous enthusiasm at the time; but I should, perhaps, explain a little more fully the reason for it. For some time I had been a variance with most of my colleagues and others working in the field concerning the type of experiments which were being conducted. They seemed to me to be non-productive, brutal, and even ghastly.

"The almost universal practice was to treat deformed animals with the X-ray in order to observe the deformities repeated in the offspring. Two-headed rats, four-legged chickens, and such monstrosities were created by the hundreds. As an inveterate animal-lover, I was in a constant state of anger and indignation at these purposeless operations. What appeared to me to be worthwhile, as I have already intimated, was the development and perfection of animal species—not their degradation.

"Well, enough of that! At any rate, I was now free to do as I pleased. I had the means for my great experiment, and I resolved that it should be my life work. I would develop an animal species!"

Again Jules paused to collect himself, and this time there was an interruption.

"And I assume that as a subject you chose weasels?" questioned Zorn, speaking slowly and thoughtfully. "Why?"

"From your tone, Major Zorn, I infer that you have guessed the reason," smiled Jules. Then his face became very serious, as he continued, "I chose them because of those very characteristics which make them so dangerous now—their immense vitality, the eager manner in which they go about the functions of living, and the ease with which they may be fed. I fixed upon them after long consideration and study. I wish now that I had not," he added simply.

There was no boredom or lack of interest in the group now. His seven listeners gazed intently at Jules as if trying to guess what was coming next. He continued in a low voice, without looking up.

"There was, among my newly-acquired properties, a small island in the Sound about two miles from the Long Island shore. It had been used for a summer home. Without hesitation I fixed upon it as an ideal scene for my activities. There I should be unmolested—and I did not desire publicity. There, I imagined my animals would be effectively confined.

"I resigned from the University, and set about collecting and setting up my elaborate X-ray apparatus. From various parts of the country—and at considerable expense—I obtained a large number of live weasels. From among these I chose ten only—the very largest, finest, and healthiest. These I treated and turned loose upon my island. I had in my employ several good men who quickly became proficient in catching and handling the animals....

"I shall not go into details here concerning my work, but shall merely sketch briefly the developments that took place in the ensuing ten years. That will bring us up to date.

"Suffice it to say that from the very start I was successful. The broods of my original ten consisted, almost without exception, of very fine animals. But again I treated only those of the greatest size and vitality—about fifteen in number. The others I got rid of, naturally.

"At first, of course, progress was very slow. I did not spend all of my time on the island—that was not necessary. I did a good deal of laboratory work and study at Columbia University. But later on matters speeded up so that practically all of my time was occupied on the island.

"In three years' time, there was an appreciable difference in size between my animals and the ordinary weasel. I had some specimens fourteen inches long.[*] The next year I treated specimens twice the size of the common animal. I observed with immense satisfaction that their agility was increasing in proportion to their size. I knew then without a doubt, that I was creating a new species.

[*] The average common weasel is nine inches long.

"It was at this time that I began to notice a remarkable development, which I had anticipated only in part. I had known that a subsidiary effect of the X-ray treatments upon animals was to increase the frequency of their reproductive activities, but had not expected any such remarkable results as I obtained in that line. Daily I became more and more astonished at the ever-increasing number of my animals. Estimating it as closely as I was able, I found that their numbers were increasing at a rate of at least ten a day. This rate of reproduction, I may as well say now, has been increasing somewhat in the manner of a geometric progression ever since!"

"GOOD Lord!" exclaimed Zorn—then: "Go on, please; I didn't mean to interrupt."

"At the end of five years practically all of my time was occupied with my work upon the island. Things were happening a thousand times faster than I had expected, or even hoped. The increase in size of the creatures was actually noticeable from month to month, due to their extremely rapid breeding and the accumulative hereditary tendencies resulting from my persistent X-ray treatments.

"I was elated. No apprehension or misgivings found place in my mind, even when the creatures became so large and strong as to be quite difficult to handle. I was still treating only the finest specimens. (At the time of treatment, they were also branded for convenience in identification.) The others were slain, and quickly disposed of, I can assure you. Weasels have no cannibalistic scruples!

"Well, to be brief, things progressed faster and ever faster, until, finally, the project got out of control. Year after year, I pursued my work, with a fanatical zeal—as it seems now. I believe that my assistants thought I was mad.

"Feeding became more and more difficult and expensive. The island swarmed with the creatures.

"It was in the eighth year that they finally developed to the point where they were seriously dangerous. One of my assistants was attacked, and badly wounded. It may sound strange to you, but it is true—that we walked around in light suits of chain mail, which I had specially made to protect our bodies. After a time, however, it became impossible to go out without being knocked down and badly bruised. The end was near....

"One by one, my men left me; and further treatments became impossible. And at last, a year ago, I was forced to definitely abandon the project. As I thought it over, I found that I could do this cheerfully; for, after all, my experiment had been a success...."

"Decidedly!" murmured Dr. Matthews, almost to himself.

"A few of the creatures, which I had managed to confine in steel cages, I took away with me for purposes of study and exhibition when I should make public the report of my work. The remainder, I left to their fate—there seemed to be nothing else to do...."

Now a shadow passed across the narrator's face, and he appeared to be in danger of losing the self-control which he had maintained so long. His lips tightened, and his brow furrowed.

"A few days before my final departure from the island," he resumed, "I had observed with some trepidation a number of the creatures taking to the water on the south side and swimming off in the direction of the Long Island shoreline. The thought of this happening preyed upon my mind continually, and a week later I drove my launch back to the island.

"Without the necessity of landing I quickly saw that there was an almost unbroken line of them swimming strongly towards the mainland. I followed their course, and there was no doubt that a number were reaching their destination. I was astounded—it had never occurred to me that they would or could do such a thing...."

As he paused, Enright Healy, who had hitherto kept silence, spoke thoughtfully. "The rats from the dumps on Riker's Island were swimming over there for years, before we managed to exterminate them."

"True," admitted Jules uncomfortably, "I should have foreseen it.... I was mad—or foolish—I don't know what....

"Well!" he said more loudly, pulling himself up, "you have my story. I went to Dr. Matthews, as he has told you. He was very kind; he did his best—but it was like searching for a needle in a haystack...."

"Thank you, Dr. Jules!" said the Chairman, rising. "Now, gentlemen, I think we have most of the facts; but let us sum up. With his permission, I shall ask Dr. Jules a few questions."

THERE was considerable restlessness around the table now, as not a few of the Commissioners looked as if they would like to speak; but the Chairman continued.

"We have, then, on a small island two miles or so from the Queens shoreline, a large colony of the animals which Dr. Jules has described to us. We have good reason to believe, moreover, that there is a colony—or colonies—on Long Island itself; and that more are arriving all the time. These animals are definitely dangerous to human beings, are they not, Dr. Jules?"

"They are," said Jules. "We have evidence of that!"

"And there is good reason to believe that they are steadily becoming more dangerous?"

"Yes."

"Why?"

"Because they are doubtless multiplying with tremendous rapidity, and because—" here Jules paused, and then concluded with extreme earnestness, "—because they are getting hungry!"

"Will you explain that a little more clearly?"

"I am convinced that the weasels have up to now been subsisting on the rats and other small animals which are plentiful in the low-lying regions where they live. This supply is now becoming exhausted, and they are turning to larger game."

"Yes! Well, gentlemen, we have the facts; and are prepared to consider whatever suggestions any of you may have." Matthews looked around, and sat down.

"Obviously," burst out Healy, "the first thing to do is to clean up that colony on the island!" A plane with bombs—both gas and explosive—would do it in ten minutes."

"I don't know—" began Dr. Jules doubtfully.

"Obviously!" repeated Healy, fixing the other with an unfriendly eye.

"Please don't misunderstand me," said Jules wearily. "I have no objection to the killing of the creatures; in fact, I have spent the better part of a year studying how it could best be done..."

"Well, it doesn't seem so complicated to me," assured Healy complacently. "We'll kill 'em—don't worry!"

"By the method you suggest, you will certainly drive them from the island; but as to your killing many of them, I doubt it!"

"Now look here," reassured Healy, "I can have a dozen police launches and a hundred men on hand—with plenty of ammunition. I don't think that any of those beasts of yours will get very far by swimming!" He turned to the Chairman. "How does that sound?"

Matthews looked around the table questioningly. There was a murmur of assent.

"I move," said a Commissioner, "that Mr. Healy be empowered to carry out his plan."

"All in favor," said Matthews, rising, "so signify!"

Five Commissioners so signified. Jules never looked up.

"Carried!" said the Chairman decisively. "Now I suggest that we turn our attention to the problem in Queensboro itself." He reseated himself.

"There, of course," pointed out Zorn, "is a different proposition. They are not all collected for us; they are scattered over a large territory. As far as I can gather," he added in annoyance, "nobody has ever had a sight of one!"

"Yes," admitted Matthews, "but we know pretty well the kind of place they live in. Dr. Jules, with his knowledge of their habits, should be able to indicate pretty well the places most infested."

Dr. Jules nodded. "I have here a map on which I have outlined, to the best of my ability, the danger areas." He passed it across the table. "As you can see, the two worst spots are the extensive dumps and marshes west of Flushing and the marshes between Bayside and Douglastown. I am certain that there is a considerable colony at each of those places."

"Good!" exclaimed Matthews, "now we are getting somewhere."

"It seems clear," offered Healy, "that the first thing to do is surround those places—lay a regular picket line."

"You bet!" agreed Inspector Kelly violently. "We don't want any more people killed—that's a bad business! Six is enough! But it'll take an awful lot of men," he added, shaking his head worriedly.

Major Zorn, who had long since gotten over his annoyance and was now as keenly interested as anyone, spoke heartily. "That's where I come in, Inspector! I can have two hundred men on the spot in a couple of days and five hundred within a week. What about it?"

"That's the stuff!" Kelly grinned with relief and enthusiasm. "We'll picket 'em so even a cat couldn't get out!"

"You will not be dealing with cats," reminded Jules in a troubled voice. "Your plan is, of course, the only possible one at the moment; but I must warn you in all earnestness that every man will be in serious danger. Why, one of the creatures could leap clear over the head of a standing man—or more likely upon his head!" he finished grimly.

"Well, we can see, and we can shoot, I guess!" contended Kelly confidently. "We might even make some little sallies into the enemies' territory—eh, Major?"

Zorn smiled, and nodded; but it was to Jules that he spoke. "I suppose the real action will be at night?" he questioned.

"Exactly! The weasels do most of their hunting then. During the daylight hours they stick pretty close to their burrows. You will need all the light you can get."

"Bonfires and searchlights," murmured Zorn. "We'll do the best we can."

AGAIN the Chairman rose, and went through the formality of taking the vote which was this time unanimous. "Now, gentlemen, we are not quite out of the woods," he continued, smiling. "To finish the job up right we must exterminate the species; and it is supremely urgent that we get after the animals in Queensboro without delay."

For the third time Healy was first with a suggestion. "Why not use the same tactics? When we have the bad spots well surrounded we can bomb the things from a plane—not with gas, if course, but—"

Dr. Jules leaped excitedly to his feet. "Mr. Chairman! I am strongly opposed to the suggestion. It won't work. I know—" here he hesitated, looking desperately around the board, the sympathies of the group were not with him. Suddenly, however, he had a saving idea. "Mr. Chairman, I suggest that Mr. Healy wait to observe the results of his attack on the island before he tries it on the mainland!"

Matthews looked around. Several were nodding thoughtfully. "That seems quite reasonable," he agreed. "We must, of course, proceed with caution." He looked questioningly at Healy.

"I agree," said that gentleman shortly.

Jules sank down with a sigh of relief. The Chairman, however, now looked at him inquiringly. "Dr. Jules mentioned a while ago that he has been working for some time on our present problem. Undoubtedly he will have an alternative suggestion."

Jules' whole manner suggested that this was a question he had been dreading. Pain and uncertainty were only too evident in his expression.

"You gentlemen will think me a fool," he began brokenly, "when I admit that I have only one meagre idea—and that not at all sure of success. I may exaggerate the deadliness of those—those damnable creatures—I don't know..."

"But what I do know," he continued with a laggard seriousness that drew the astonished attention of all, "is that mankind has never had to deal with anything like them before! I, who long ago objected to monstrosities, have created monsters a thousand times more horrible. They are not creatures of this earth—they are products if my rash and mistaken science. Through my minimal efforts hundreds—nay, thousands—of innocent human beings shall meet their deaths, God!—I—"

"Now, Dr. Jules," put in Matthews kindly, "I am sure it is not as bad as all that! Hadn't you better tell us your plan?"

To the relief of all, this suggestion appeared to calm the scientist. When he spoke his manner was almost businesslike.

"Yes—yes! Well, two months ago I hit upon a weapon which I believed could be used against them. As a test I tried it on those that I had confined. They died—and I was glad! I hated them—they were vicious and evil—their red eyes stared at me horribly—"

"And the weapon was?" reminded Matthews.

"Disease! For weeks since then I have been working day and night to perfect a serum which is now ready to be used...."

"Humph!" grunted Healy, and his tone reflected the attitude of a number of the Commissioners. Others, however, appeared keenly interested.

"Your idea is to capture a number of the animals and inoculate them, in the hope that they will spread the disease?" offered Zorn.

"Yes—and I am anxious to see what I can do," he looked appealingly at the Chairman.

"To me," stated Matthews, "Dr. Jules' idea seems very good. Its one drawback is, of course, that the process would be slow. But we should, in my opinion, be guilty of extreme negligence if we failed to take advantage of the services of one who knows more about the subject in hand than all the rest of us put together!" He smiled around the table.

"I propose," said Zorn instantly, "that Dr. Jules be given free rein to act as he sees fit—as I have no doubt that he is anxious to give all his time to this matter; and that he be empowered to call upon me or upon Inspector Kelly for any helpers that he may need at any time."

There was no opposition to this motion, and the vote was unanimous.

Kelly stirred uneasily in his chair. "It seems to me," he burst out suddenly, "—'though it may be a small matter—that Dr. Jules ought to have somebody with him—regular, I mean.... Like a body-guard, because it's goin' to be dangerous business." He paused uncertainly; then grinned. "If a big-shot gangster gets five or six, the doctor ought to rate one—anyhow!"

"Very true, Inspector!" agreed Matthews.

Jules was looking much happier, now that his work was definitely cut out for him. "Then I have a request to make," he said. "I have been very much impressed by the bravery and efficiency of Officer Connolly on that horrible night. I should be delighted if I could have him with me—that is, if he would like it...."

Connolly's eager face left no doubt on that score.

"No trouble at all!" said Kelly heartily.

"Then, gentlemen," said the Chairman, rising, "I think we have done all that we can, for the time being. Has anyone anything further to say?"

There was no word.

"Then let us adjourn. Undoubtedly we shall meet again—let us hope, cheerfully. For the present, I think I am safe in saying that we have earned our lunch!"

IN the bright morning sunlight, three days later, a procession of ten police launches filed through Hell Gate; and, passing close to Welfare and Riker's Islands, roared out upon the waters of the Sound.

Officer Pat Connolly—very proud of his new official status—leaned over the rail of the foremost and largest launch, gazing cheerfully ahead. Beside him, on a heavy standard, stood a machine gun of business-like appearance; and upon the top of this his right hand rested in proprietary fashion.

Dr. Jules, who had been talking to the pilot, now came forward, and stood beside him. His appearance and whole demeanor were considerably improved. Action of any sort was a tonic after long days and nights of worry and dread.

"Well, Officer," he greeted cheerfully, "I guess you are planning a little revenge party;—is that it?"

Half unconsciously Connolly raised a hand to his throat. "That's right, sir," he agreed devoutly, "I'm goin' to pot a few of the beasts if Lizzie here don't clog on me!"

Jules regarded the vicious-looking weapon. "You understand this type of gun?"

"Sure do! Used one all through the war... Took it to bed with me, even—'cause it was most generally warm, y'see."

The other smiled; but his thoughts were already upon other matters.

"That's how I happened to get this one this morning," explained Connolly.

For a time both men were silent, gazing abstractedly at the foamy waves which dashed away from the side of the speeding boat. Then:

"Have you seen the morning papers?" asked Jules in a peculiar voice.

"Yes sir," said Connolly, shifting uneasily. The scare headlines proclaiming the news of three more casualties during the night still danced unpleasantly before his eyes. Each morning they were larger and more terrifying. All the front pages now carried boxes with statistics; "Known Dead—9, Missing—6, Wounded—3, (all policemen)"—so ran the morning's score. Editorial departments were in a seething rage.

"It's bad, sir; but Zorn's coming in today with a regular army. Things'll be better tonight."

"Let us hope so, Connolly!" breathed Jules fervently. But after a pause he persisted: "Did you happen to read last night's Star?"

"Why, yes sir," admitted the other, still more uncomfortably. Then he burst out hotly, "An' of all the damn'—excuse me, sir!—of all the crazy bunk I ever seen—! 'Criminal negligence', huh?—why they practically called you a murderer—an' you workin' an' sweatin' blood! What've they been doin'? Gosh, I—"

"Thank you, Connolly!" interrupted Jules quietly. "But a good deal of what they say is true. I have been as a child playing with fire."

Officer Connolly shook his head, grumblingly, and subsided. They listened to the swish of the water, as the launch raced onward. The ugly shoreline of Astoria had now slipped by, and they were further out, opposite Corona.

"A beautiful morning!" commented Jules.

It was. In the sunlight the little, dancing waves shone and flashed brilliantly. In a cloudless sky the April sun was getting warm for the first time, and the dozen or so policemen on the deck sprawled in lazy attitudes, obviously enjoying themselves.

"How much farther is it, sir?"

"Look almost straight ahead—a little to the left."

Connolly saw a tiny island, dark against the brightness of the water. He studied it curiously as it grew before them. It was well wooded, though the trees were not large; and soon he made out a great, low, rambling house near the center.

"I don't see anything alive, sir," he complained.

"Wait!"

The launch had now dropped to half speed, and was nosing in towards the shore. The others followed suit, and ranged themselves at random alongside.

"Watch!" exclaimed Jules suddenly.

A kingfisher, which had been swooping and darting above them, had now retired to the shore, and come to rest on the bare branch of a tree some fifteen feet above the ground.

"What sir?"

"The bird, man—the bird! See?—on the—"

From a clump of bushes a dark streak shot into the air. The startled bird was snatched viciously as it attempted to fly; and a great brown creature dropped lightly to the ground, already mauling its prey.

THE men on the boat gazed at it—open-mouthed, silent. The long, powerful body was humped in the center, like a great bent spring; the head was bullet-shaped and ugly; there was about the whole animal a suggestion of terrible power and deadliness that sent shivers up and down Connolly's neck. He hated it instinctively—it was somehow repulsive—evil. "Gosh!" he breathed, "weasels was never meant to be that big!"

Jules answered him grimly. "You are right, Officer Connolly! What nature never meant to do, I have done...."

There were excited exclamations as, drawn by the scent of blood, several more of the creatures appeared; two—five—seven—a dozen, writhing about and uttering harsh, screaming cries. But nothing was left of the meagre prey except a few feathers, and within a minute the shore was again unoccupied. Loud comment and conversation, mingled with jokes of the "Let's go ashore and have a picnic!" type, broke out upon all the boats.

"No—nature never meant those things to be," continued Jules sadly. "To a scientist is given great power—for knowledge is power. If he is a rash fool, and uses it to tamper with nature's plans, he must pay—and others must pay...."

Officer Connolly was beginning to wish fervently that he had held his peace, when a low drone in the sky created a diversion.

"Here she comes!" he exclaimed.

"I must speak to the officer in charge," muttered Jules; and, turning, he walked quickly aft.

Their engines picking up, the launches swung around, and retreated from the island. At a distance of a quarter of a mile they formed in an orderly line about a hundred feet apart. The plane—a huge tri-motored bomber—now circled lazily above them.

Connolly—suddenly bewildered—was relieved when, a moment later, Dr. Jules rejoined him.

"Say!" he objected, "I thought we were going to surround them."

"Captain Jones agrees with me that we had best concentrate our forces on the south side," explained Jules. "The animals that start north will not be likely to get anywhere."

"Gee! I'm dumb," admitted the other sheepishly. "Guess I expected 'em to swim all the way to Connecticut!"

"I doubt whether many will try it; they will come this way. They have uncanny instincts." He looked worriedly up and down the line. "I'm afraid our force is very weak," he muttered. "I tried my best to get them to send more boats and men, but—"

From the top of the cabin behind them three shots rang out—a prearranged signal to the men above. With a roar the plane swooped over the island. In the clear air the falling projectile was easily seen....

BOOM!

Into the air shot a great column of dirt and debris.

"Hope he keeps right on bein' a good shot!" grinned Connolly, as the plane circled back. "Boy, I'm glad the wind is blowing north! When he starts usin' gas we don't have to wear these things." He kicked a mask lying on the deck.

"We wouldn't use much gas otherwise," commented Jules. "There are the people on the shore to think about...."

BOOM! BOOM!

"Coupla bull's-eyes!" exulted Connolly; and then, suddenly: "Good night!—Look!"

The whole shore and visible surface of the island appeared to be moving—swirling, eddying, leaping. Angry, unearthly screams filled the air.

"There's millions of 'em!" he gasped; and, tight-lipped, set to work at his gun. "Gotta get Lizzie ready!"

The great plane had circled again.—CRASH!

"Gas!" shouted Connolly; suddenly he seemed to freeze—"What about ships out in the Sound? Good night!"

Jules was quick to reassure him. "A general warning has been circulated for three days. It is this wind that we have been waiting for, you see.

"There you are!" he exclaimed suddenly. "Get ready!"

A HUNDRED yards out something was moving towards them in the water. Small ripples in the form of a V stretched out behind it.

"You can come a little nearer, Mister," greeted Connolly grimly. "I ain't goin' to waste no shots on you!" He squatted behind his machine, waiting. The thing came steadily on. Soon they could see its bullet head and red eyes....

Rat-tat-tat-tat-tat!

It swerved to the left, but did not stop. Five more shots, Connolly pumped out. Now its pace slowed, and its course became irregular.

"Good night!" he growled disgustedly, "Do I have to put enough lead in 'em to sink 'em?"

"You are not shooting dogs," reminded Jules.

"Well, that's all he gets," decided the officer, " 'cause here's another!" He swung his machine around, and again it rattled forth a stream of lead.

Now desultory firing had begun all up and down the line. Steadily the volleys became more prolonged, as there came from the island an ever-increasing number of the swimming animals. Soon the surface of the water was dotted with their heads—poor targets at the best.

The men lined the rails, firing steadily—loading and reloading with swift intentness. Faster and more desperately they worked as their targets multiplied from tens—to hundreds—to thousands....

On and on the battle raged. The banging of rifles, the rattle of machine guns, the sharp whine of ricochetting bullets, the occasional explosions from the island—all merged into a terrific uproar which never slackened.

"They're gettin' by!" shouted Connolly, viciously slamming a fresh magazine into his gun.

Dr. Jules, who had long since found a weapon, and was using it to the best of his ability, merely nodded.

It was true. Long lines of moving heads stretched away behind the boats. Connolly snatched a moment to look around. "About half!" he snapped, and swore bitterly. He ducked involuntarily as a glancing bullet whistled over his head. Some of the men, demoralized, were shooting between the boats.

"Hell!" said he.

Captain Jones, a stocky, red-faced man, leaped to the top of the cabin. "Shoot north, you fools!" he bellowed. "One shot to a beast!" The word was passed along. Jones came puffing forward.

"No use chasin' 'em up, Doctor—with more comin' all the time—huh?"

Jules nodded.

"We're runnin' low on shells," said the Captain heavily. "Can't keep this up forever!"

Again Dr. Jules merely nodded. His face was set and hard. He fired regularly—methodically.

On and on went the steady din. Men sweated and swore at jammed guns or mislaid ammunition. Time passed....

And then—shortly after noon—the firing slackened. Ammunition was giving out. Some boats had none at all, and the men stood around, helpless and irritable. The numbers of the swimming animals had greatly decreased, but soon those that still came went past unmolested. The battle was over....

Officer Connolly, his last round of shots fired, spat disgustedly at his smoking weapon. His face, lined with sweat and grease, showed discouragement and an ever-rising hint of something more. He looked at Dr. Jules hesitantly—almost pleadingly....

"We ain't done much good, have we sir?"

Slowly Jules turned, and looked at him from haggard eyes.

"We have done immeasurable harm," he said tonelessly.

ON a lonely and unused road, their figures vaguely outlined in the night, ten men played at a grim game—grim in its very simplicity. As they strolled aimlessly about, or stood talking softly in groups and pairs, there appeared in their manner and bearing a certain tense expectancy.

They were within the danger zone. At a radius of two miles there stretched around the spot a circle of blazing fires and white, darting lights, which was the picket line. No cars now passed along the road which, two weeks ago, Officer Connolly had used; and the remote circle of light served only to make darker the place where the men waited.

Strapped about the neck of each was a high collar of heavy leather; and at the belt, in addition to an automatic of large caliber, hung a small, strongly built instrument resembling a doctor's syringe. Five were policemen, four—militiamen, and the last—Dr. Jules.

Jules' call for "nine men willing to undertake a very dangerous but necessary work" had been speedily answered. With his picked volunteers about him he had briefly explained what must be done; outlined the advantages and disadvantages of different methods of procedure; and, finally, divulged his own daring plan. The men's first astonishment had quickly turned to enthusiasm and hearty approval....

"Of course, gentlemen," Jules had explained, in conclusion, "there is little danger of a mass attack unless blood is drawn. The creatures are, essentially, lone hunters; but the scent of blood will draw them by the hundreds. If, therefore," he emphasized seriously, "so much as a drop of blood is shed, we must retreat. We shall have two armoured cars for that purpose, and they will be ready tonight with all necessary equipment.

"I cannot tell you how grateful I am for your cooperation and faith in me.... I—I—Well, goodbye until tonight!"

Afterwards, Patrolman Dugan, speaking to his friend Connolly, nodded his head weightily; and declared, "I don't know much about these here scientists, as a general thing—but there's one that's a man!"

"You said it!" agreed Officer Connolly.

Now, on the scene of action, Dr. Jules paced up and down impatiently, his head bent, his hands clasped behind his back. To the occasional remarks addressed to him he replied in curt monosyllables or mere gestures. The constant strain under which he laboured made it difficult for him to be friendly. The men realized this; and, during the nights they had spent with him, had come to respect him tremendously for it.

"Yes," said Connolly, conversing in low tones with Patrolman Dugan, "he's the only guy on this job that knows what he's doin'. You oughta seen that big shot Healy eatin' out of Doc's hand after he pulled that boner bombin' the island! 'Yes, Doctor!' was all he sez when Doc tells him to start gettin' in a big supply of lumber an' concrete an' buildin' materials...."

"What for?" gaped Dugan.

"Well, I don't rightly know," said the other, scratching his head, "but this is a bigger thing than most people realizes—except Doc.... You can be sure that—"

With a thud and loud, startled exclamation one of the men who had wandered slightly apart from the group toppled to earth. The others faced about, straining to see. The game was on....

Even as the great creature upon him tore angrily at his protecting collar the prostrate man snatched the syringe from his belt. Deep into the furry body he jabbed the sharp needle....

"Come!" he yelled breathlessly as he pressed home the plunger.

His nine companions pounded forward, shouting and discharging their pistols into the air. Their violent sally had the desired effect. In a flash the attacker was gone. An angry scream floated back....

"Four for me!" gasped the shaken man, struggling to his feet. Ruefully he rubbed the back of his head. "I think we oughta spread some mattresses around to fall on!"

"DON'T worry," grinned Connolly, critically examining the other's collar, "there's one more weasel that'll have worse than a headache by mornin'! Let's see—that makes twenty-seven sick weasels in four nights. Not bad...."

"Let us hope that there are three times that many by this time!" amended Dr. Jules, who, with the help of a flashlight, was busy recharging the syringe from a bottle which he carried.

Swiftly the men were reloading guns. Half-filled magazines were not popular.... "If you can't scare 'em away, let 'em have it direct!" was the first law of the game. That had been necessary once. You had to be a good shot...

Suddenly a long, harsh wail rent the air, rising and falling, ever growing louder. The men peered into each other's faces in quick surprise.

"What the—?"

"Siren!"

"Comin' this way—"

Down the hill from Douglaston roared a great car. Behind it came another—and yet another—more....

"Off the road!"—the men retreated.

"Squad cars!" muttered Connolly, "—a whole percession! They gone crazy?"

Now they were thundering past. The last one slowed with a squealing of rubber. A hoarse shout:

"The beasts are runnin' wild in Flushing.... Need every man!"

It was gone.

"Come!" snapped Jules.

They tumbled into their two cars; and, motors sputtering into life, swung around and took the trail. Up the hill, past the line of gaping soldiers—through Bayside. Down the wide boulevard, lined with running crowds—past Auburndale. On to Murray Hill....

Jules was rattling out directions through tight lips.

"Attics—tops of houses—cellars!.... Get the other men—scatter—spread the word.... Remember, windows are no protection unless high up!.... The devils will be blood-mad—no let-up 'til morning.... Fight!"

As they bore down upon Flushing, there met them an ever-growing wave of sound—a pandemonium of shots, yells, and screams—the wild, angry screams of the hunters—the terrified, helpless cries of the hunted. Figures ran stumblingly, futilely through the streets—other figures leaped and bounded with deadly accuracy.

The cars careened into brightly-lighted Main Street, and one by one the men leaped to the ground—only to stand frozen for a moment by what they saw. Then, cursing bitterly, they sprang into action, passing back Jules' orders to those behind, dispersing in all directions.

"Oh, good God!" groaned Jules. Connolly's face was red with fury.

The broad street was strewn with bodies of the dead and dying. The rows of shops, where people had vainly sought shelter behind fragile glass, were rows of human slaughter-houses. And still there ran and leaped and screamed the blood-crazed killers. Among them, hundreds of dauntless but hopelessly confused soldiers and policemen ran in circles, firing futile shots. Upper windows were lined with pale, horror-stricken faces.

"Look out!" barked Connolly—too late. From the doorway of a shop hurtled a long, lithe form, flinging Jules violently to earth. His eyes blazing, the officer took careful aim; and fired four times. As the beast sprung away there came panting up to them a man in uniform, hatless and blood-stained. It was Major Zorn.

"Doctor," he entreated, "get out of this Hell—you will be needed—your life is precious—"

"No!" grated Jules, struggling up, "I have work here.... Where is Kelly?"

"At the subway station."

"Are the trains running?"

"As best as the mob will let 'em; but they're crazy wild, fighting and trampling each other to get in. Kelly's got two hundred men there trying to stand off the beasts, but it's only a matter of time...."

"Are the beasts spreading out?"

"Up every street!—diving through windows—God!"

"Send squads of men up every street," snapped Jules. "Get the people in attics—doors locked!"

"Right!"

"Drive to the subway, Connolly!"—and Jules leaped into the nearest car. In four minutes they were there.

"Kelly!"

"What?—what the—"

"Kelly!—I want six men!"

"Here, six of you—pile in that car! All right, Doctor?"

"Can I have you for five minutes?"

"Shoot!" snapped Inspector Kelly, leaping to the running board.

"To the local telephone exchange!" directed Jules.

ON the way he shouted to Kelly the outlines of his plan.

"Good!" nodded the officer grimly, "—they'll do it, all right!"

"Bars on the windows!" breathed Jules, as they skidded to a stop before a small, square building, "—Wonderful!"

They burst in.

"Chief Operator!" bellowed Kelly.

A small, frightened man came forward. "Yes—?"

"We want every line yu got.... You're goin' to call every number yu got!...."

"B-But, sir, it would take a long time...."

"I don't give a damn how long it takes! Start now! Here's six men to help yu if you're short-handed."

"But what would we say?"

"You will say," put in Jules, "these words: 'Awaken everyone. Go to your attic. Lock the door.'—That is all. You will save hundreds of lives!"

"All right—all right!" stuttered the little man. "I can use five more men.... See? Here and here and here—yes, that's right.... Now look...."—excitedly he instructed them.

"An' listen—yu ain't handlin' no other calls, see?" added Inspector Kelly belligerently.

"Yes sir!"

"O.K.—Now I'm goin'...."

"Take my car," offered Jules.

"Thanks!"—and Kelly flung out into the night.

The line of operators swung into action: the dialing—the wait—the crisply spoken message—the dialing—the wait....

Jules, frowning, came to a decision. "Don't wait more than two minutes for an answer," he ordered. "We can't waste time."

"And now, Connolly, you and the other officer watch them, so that you can take your turns."

Outside the uproar was dying down somewhat. Screams and volleys of shots now came from widely separated points. Several times heavy bodies crashed against the bars at the window, but they caused no cessation of the work within. The clicking of the dials, the monotonous repetitions of the voices—on and on it went. Hour after hour....

Ceaselessly Jules paced the floor. "Awaken everyone—go to your attic—lock the door—awaken everyone—go to your attic...." His head whirled. Was there nothing else to do. For the hundredth time he racked his tired brain. Nothing!

He looked at his watch. Three-thirty! Would this awful night never end?

When an operator crumpled up, and rolled from his seat, Connolly swung into his place. "One—three—eight—seven—up!" muttered the man, and closed his eyes. Clumsily the officer to work.

On and on.... Jules felt that he was going mad. Still those screams! Each one cut him like a knife. Some were near, but most were faraway.... Was ever a night so long....?

And then, of a sudden, the sky was gray; and the noise outside had ceased. They were slinking to their burrows now—he knew them well enough for that! But still he waited—waited until the first rays of the sun glanced along the ground. Then:

"Enough!" he said.

In the ghastly shambles that was Main Street, Flushing, a little group of men stood about a prostrate figure. Silently they looked down at the body of Major Rugert Zorn, Militiaman. His head was rolled back in the gutter, his throat a red horror; his wide, sightless eyes gazed up at the day that had come too late.

A sudden stream of curses from Inspector Kelly ended in a choking sob....

"He was a great guy! I got to know him good...."

Without raising his head Jules spoke in a low tone, as if addressing Zorn.

"How did the whole thing start—last night?" With an effort Kelly achieved a matter-of-fact tone. "A soldier got killed. In ten minutes there was two hundred of the brutes there. There was no holding 'em...."

"There will be no holding them," murmured Jules. He put a hand to his forehead, swaying slightly.

"It is the end.... They have tasted human blood. They have known the joy of killing men. There is something new in the world—a terrible, merciless tribe—hunters of men...."

Silently his knees doubled, and he pitched forward across the body of Zorn.

BY nine o'clock that morning every roadway leading into New York was choked with loaded cars. The railroad and subway platforms bore struggling, sweating mobs; the rumbling trains were filled to the last inch of space. All day long across the East River bridges, moved unbroken lines of vehicles. Extra ferry boats and water craft of all kinds were pressed into service. The great exodus had begun....

All day long the telegraph and telephone wires between New York, Albany, and Washington were worked to capacity, with the result that, shortly after noon, a state of martial law was declared to exist throughout the Boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens; and the residents of Queensboro were summarily ordered from their homes. Brooklyn, with its two million inhabitants, was a different matter.

And in a large, white hospital room in Manhattan that matter was being discussed.

"'Protect Brooklyn'—orders from the War Department!" grated Healy. He raised his hand in an expressive gesture. "'Protect Brooklyn'! What about all the soldiers they're sending in? About half the standing army, if I get it right. What do they plan to do if not protect Brooklyn?"

Dr. Jules stirred uneasily on the bed. "Soldiers are vulnerable. They are only human, after all. As a temporary protection, we must have them—yes." He pulled himself to a sitting posture, and continued with an incisive finality, "Healy, we must wall in Brooklyn! That is what 'Protect Brooklyn' means. I have been in constant touch with Washington for a week. I know!"

"Wall in Brooklyn? Build a wall around it?" stormed Healy.

"It is not as bad as all that. Topography favors us. Here, bring me your map!"

Healy spread it on the bed. Jules traced the lines with his forefinger. "Look! Starting down the Newtown Creek from East River—straight across to Jamaica Bay. It is scarcely seven miles. That will be all that is necessary."

"You're right!" agreed the other, relieved. "How much time have we?"

"You must move with all possible speed. See! Down the marshes of the Flushing Creek, through the low-lands and dumps of Maspeth, the creatures are spreading. No time must be lost!

"You will have thousands of willing workers at your command—only too eager to save their homes. Without trouble you will be able to commandeer trucks, vehicles of all kinds—all that you can use...."

Already Healy was at the telephone, his map spread out before him. "Hello—Morris! Get a map of Brooklyn—now, get this!" Skillfully he traced the line of the fortification.

"Drop everything! Get down there.... Lay it out! Grab what you want from every lumber yard and builder in Brooklyn. I'll fix that.... Wait!"

Jules had interrupted. "Wait—this will cut your work in half: Utilize buildings and structures of all sorts. A street lined with houses—windows boarded up—is your wall half made!"

"Right!—Good! Get this Morris...."

So the work was begun. Healy left for City Hall. Jules lay back with eyes closed—but in half an hour Inspector Kelly was with him.

"How you feeling, Doctor?"

"Better. I shall be up this afternoon."

"Wish you'd stay where you are 'til tomorrow. You're tuckered out! After all, there ain't nothin' to do but help the people get out. They don't need much urgin'! It's mainly a traffic job."

"I suppose you are sending a number of them farther out the island?"

"Sure!—we got to.... About half of them. Even at that we can never get 'em all out today. It's a mess!"

"What preparations are being made for the night?"

"We're gettin' organized. Goin' to use banks and jails—places with bars on 'em. Attics for the rest of 'em—that worked good last night... Gee, you done a good job!"

JULES smiled wanly. Then he became very serious.

"Do you realize, Inspector, that the whole of Long Island with the exception of Brooklyn—which we shall protect as best we can—must be evacuated before we are through with this awful business?"

Jules' associates, including Inspector Kelly, had gotten into the habit of accepting his lightest words as undoubted truths; but now the officer could not suppress an exclamation of astonishment.

"Good Lord! Why?"

"There is no other way. The territory must be surrendered. Until then our hands are tied by the very presence of human beings, and the scourge will flourish." He sighed. "Disease has failed, since we can no longer hold the beasts from spreading."

"Well," considered Kelly slowly, "there's nothin' to keep the railroad trains from running... And ships will take care of the rest.... It'll be a big job! When it's done—what then?"

"That, I am sorry, I am not at liberty to tell you!" said Dr. Jules.

HOUR after hour, throughout a day only too short, the great migration continued. Manhattan was hopelessly over-run. Every hotel, every available shelter was quickly filled to overflowing; and long, unbroken lines of the refugees stretched onward, north into New York State, west and south into New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Homeless, to a large extent destitute, they nevertheless gave thanks for their safety; and pitied those not so fortunate.

And, beginning at four o'clock, from north and south and west fleets of heavy trucks laden with soldiers entered the city; and, rumbling out across the bridges, were greeted with the heartfelt cheers of the frightened people.

As dusk began to fall, the streets cleared of humanity, as if by magic. Only soldiers remained visible, placed in large detachments at strategic points—at the heads of bridges, and, in Brooklyn, four deep along the alread well-defined line of the fortifications.

And when the long night had finally passed, people poured thankfully out into the light to learn that the beasts were spreading. Even as they prepared to take the roads to safety, they told each other in awed voices of the incredible distances covered by the mad, blood-hungry killers; of the unexpected casualties away out on the island; of the soldiers that had died....

This day was a repetition of the last. Dr. Jules, again on his feet and, followed by the dogged Connolly, argued relentlessly for a second great wall along the Manhattan shore of the East River. The authorities were doubtful. But that night, when there were seven violent deaths in the Bowery and three in fashionable Tudor City, he had won his point. Before noon on the morrow the labor had started. The difficulties were tremendous, but when men are desperate much can be done.

Every truck and available vehicle in the city was commandeered to haul lumber, cement, and steel from far and near. Tens of thousands of able-bodied men, skilled and unskilled, were pressed into service. At night, lines of soldiers, aided by hundreds of powerful searchlights, guarded the shore as best they could. So, day after day, the tremendous structure grew;—and in the great metropolis all ordinary business was at a standstill....

Meanwhile, the evacuation of Long Island continued, proceeding automatically at first, but speeded after a week by Dr. Jules who emerged from a long and constant communication with Washington with a definite order, covering the whole territory. By boat and train people abandoned their homes—and gradually, as days grew into weeks, the evacuation was complete. In many cases force had to be used. That was inevitable. Many casualties occurred—the death lists still grew. Under such conditions accidents—miscalculations—are unavoidable. But even violent death may become a commonplace....

Dr. Jules left for Washington.

PRECISELY a month after its first meeting, the Emergency Commission reconvened about the long table in the conference room in the Municipal Building in New York City. But where there had been seven, now there were five; and, whereas before, only one had been seriously worried, now, they were all definitely uncomfortable.

"Dr. Jules has telegraphed that he will be late," Matthews informed them.

This news was received in silence—a silence that continued minute after minute, steadily becoming more oppressive. A stranger, looking on, would have been astonished at this novel method of conducting a meeting—astonished that five such responsible looking men could sit so long and say nothing.

As a matter of fact, the silence of each was similar to that of a school-boy who has not learned his lesson, and fears that at any moment his ignorance may be discovered. For each Commissioner was groping desperately in his mind for a solution to the problem which confronted them—and not finding it.

Time and again they pictured in their minds the situation. Long Island alive with dangerous creatures—real, purposeful enemies of mankind. Manhattan and Brooklyn reasonably well-protected. But the creatures multiplying with insect-like rapidity were becoming maddened by hunger. The doubtful safety of Staten Island, New Jersey, the Bronx, Westchester—all the surrounding Mainland. The fearful uncertainty of what the creatures, rendered desperate by hunger, might be capable of....

Each man recalled vividly the scene along the high walls. The growing swarms of great beasts. The crowds of people covering every vantage point—packed on the roofs of buildings, lining the top of the wall itself—gazing in endless wonder and awe at these things that leaped, and screamed for their blood....

Dr. Matthews cleared his throat. "Well," he said, "I see no reason why we should not discuss the situation, and consider what is to be done. I fear there is no escaping the fact that our best efforts have, up to now, been dismal failures; although I cannot see what we could have done that we did not. As a body we have done little to help matters. I need hardly say that this is our last chance.... Now, what is to be done?"

"I know several things that cannot be done—if that is any help!" answered Healy with bitter irony.

"Even negative ideas might conceivably be useful, Mr. Healy," insisted the unsmiling Matthews.

"Well, in the first place," began Healy irritably, "we can't attack the things; our hands are tied there. The whole country around is up in arms. You know what happened when we bombed that little island! You can't blame 'em for that. We don't know what the beasts can do; nobody does. If a hundred thousand or more of 'em started swimming, there's not much doubt that a lot of 'em would get somewhere.... Then—well, I don't have to talk about that!"

There was no comment. Each man had gone over this a hundred times in his mind. The beasts running free on the mainland! Beyond that point they refused to think....

"On the other hand," snarled Healy, "we can't let 'em alone, either. In another week they'll have eaten everything there is to eat—and then what'll they do? Start swimming anyway!..."

"Couldn't we," offered one of the others hesitantly, "get a lot of boats—enough to take care of them when they started to do that?"

"Yeah!" sneered Healy, "we'd look pretty trying to stop them at night in the water, wouldn't we? If we had a net about fifty miles long we might do something towards stopping them—sure!

"To sum up, then," concluded Healy with mock ceremony, "we cannot molest the creatures, and we cannot let them alone.... Do I hear any suggestions?"

"Hardly a useful conclusion!" snapped Matthews.

"Hardly expected it would be!" returned the other.

Inspector Kelly's inborn dislike of bickering made him attempt a diversion.

"The other day I was talkin' to Captain Reilly—he's a Staten Island man. We came to about the same conclusions as Mr. Healy. 'Then,' says Reilly, 'there's only one thing for you to do—you got to feed 'em, and keep 'em contented!' "

THIS sally was received with silent indignation by the others, and Kelly subsided.

"Perhaps," pursued the Chairman, after a pause, "it would be suggestive for us to outline the characteristics which a weapon must have, to be used against them. First and foremost, of course, it must be something that will not drive them from the island...."

"That's the whole thing!" put in Healy.

"But the minute we go after them, they'll start to swim," objected Kelly. "We can't very well try to kill them, and keep it a secret from them!"

"We must!" insisted Matthews. "There we have the first requirement: it must kill without alarming them...."

"That means instantaneous death," one of the others pointed out, "—not an easy thing to try on those brutes!"

"Yes," agreed the Chairman, "unless we can attack each and every one of them at the same moment—which is, of course, ridiculous—death must come swiftly and silently so as not to alarm the others.... Second requirement: it must kill instantaneously."

"Some sort of odourless gas—" began the other, but even as he spoke he shook his head vigorously.

"Not geographically feasible.... Third requirement:" pursued Matthews methodically, "it must be under perfect control."

"Disease?"

"Much too slow!.... Fourth: it must do the entire work in a very short time...."

"Now there's a riddle for you!" burst out Kelly.

"Yes, that is a riddle—and without an answer, I am afraid," admitted Matthews in discouragement.