RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

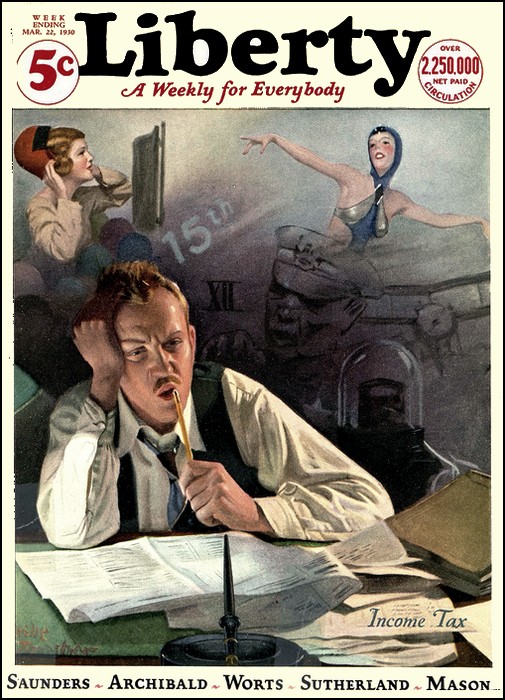

Liberty, 22 March 1930, with "The Sapphire"

In 1933 A.E.W. Mason developed this story into a full-length novel, which was published in the same year by Hodder & Stoughton in London and by Doubleday Doran in New New York, 1933. Click here to access the RGL edition of this novel.

IT was one o'clock in the morning. The light from six shaded candles gave softness and mystery to the faces of the women and shone down upon a mahogany round table in the pleasant disorder of silver and porcelain which graces the end of a convivial supper party. Elbows were propped on the table's edge, eager voices caught and tossed back the conversation like a ball, tiny columns of smoke rose from cigarette and cigar.

It was the hour when theories are swiftly invented to lead on to a story as an illustration. A speaker had just thrown out the suggestion that the perfection of the old fables was due to the fact that when they were composed there was no traveling. "There was a unity, a completeness," he said. "Now the most stay-at-home of men travels so far and meets for a second so many strangers in as great a hurry as he, that his life, is a jumble of sensations, a thing without a pattern, as his stories are." He paused for a fatal moment before he entered upon his illustration and so never related it at all. For a quiet voice cut instantly across in front of him:

"Yet this afternoon I heard the last word of a fable as rounded and complete as was ever written, though bits of it happened here and bits by the side of a distant river and the characters came together from the opposite edges of the world.

"There must have been something, however, to give your fable unity," said another.

"To be sure there was," returned Colonel Strickland. "A sapphire."

The ladies were instantly of one mind. Colonel Strickland must tell his story. For one thing, the heart of it was that most thrilling of subjects—a jewel. For a second, Colonel Strickland carried about with him a curious air of aloofness and romance which in itself aroused expectation.

The ladies were instantly of one mind. Colonel Strickland must tell his story.

For one thing, the heart of it was that most thrilling of subjects — a jewel.

IT all began, so far as I am concerned [Colonel Strickland commenced] five years ago. I had walked across the hills from the Yunnan Province of China down to Bhamo on the Irrawaddy, and there took a cabin on one of the big river steamers to Mandalay. Its captain was an American, Michael D. Crowther—what the D stands for I don't know to this day—with the lean, angular, hard face of his nation, and the twinkling eye which belies the hardness. He was one of those deceptively secretive people who are unusually communicative up to a point—the point where their confidences would become interesting.

"I shall cast off early in the morning, colonel," he said to me over a whisky and soda. "This is my last voyage on this old river, and I am anxious to get down to Mandalay and have done with it. I am becoming Orientalized—that's my trouble. I'm from Detroit and I have got to get back to the eager life suitable for an American citizen."

He cast off, in fact, before daylight, and I was very glad that he did. For what with the breathless night, the high bank beneath which we were moored, and the great double-decked lighter lashed to the other side of the steamer, the heat in my cabin was abominable. The river, however, was very low, and, in spite of the continuous chanting of the two men with the sounding poles, twice during the day we grounded upon sand banks, and on each occasion it took time to wriggle and twist her off.

TOWARD evening Captain Crowther came down from his perch on the roof with his helmsman to the second wheel on the big triangle of open deck in front of the saloon. And from now on a pale gray beam stretched out from the huge headlight in the bows and lit up the red-and-white poles which marked the channel and the sand banks with a silvery radiance. We were approaching the village of Tagaung, and I said to the captain innocently:

"I suppose that you will tie up there for the night?"

I saw the chief officer compress his lips to prevent a smile, and Captain Crowther looked swiftly and searchingly at me, as if he suspected a reason for my question.

"No, colonel," he answered deliberately. "I shall try to make Thabeikkyn. I shall wait just half an hour at Tagaung."

"There are a great many bags of rice waiting there," the chief officer suggested.

"Then the next steamer will have something to do," said Captain Crowther slowly; and at that moment we bumped for the third time upon a sand bank and stuck fast.

Before we were free again, darkness and the stars had come and our gray beam had changed into a broad ray of dazzling gold along which myriads of white moths streamed like snowflakes, to burn to death on the great glass of the headlight.

We rounded a corner and the bright light of a petrol storm-lamp showed us the landing place. Captain Crowther sidled in gingerly, and switching round his headlight, revealed to us suddenly in a circle of golden light one of those spectacles of which, for my part, I shall never tire. A brown slope of beach; fat bags of rice piled high and in orderly rows; the whole population of the village squatting and talking, with the storm-lamp in the middle, their headdresses and skirts of gay and delicate colors glistening in the light; the brown shoulders of the men, the white jackets of the women; here and there a Buddhist monk draped in his bright saffron robe; on the top of the bank, the thatched cottages and the inevitable pagoda; and all around the jungle—whispering. That was Tagaung.

I went ashore as soon as the gangway plank was down. To my surprise I was immediately followed by the captain. He paid no attention to me, but went straight up the beach like a man upon urgent business. He was met by a girl with a rose in her hair, who led by the hand a child too old, I suppose, to sit astride of her hip in the way children have in Burma. And the three of them went aside out of the glare of the headlight into the shadows.

Captain Crowther was the last to come on board again when our half hour had elapsed, and he carried a packet tied up in brown paper in his hand. He sprang very alertly up the ladder to the wheel, gave the order to cast off, and as the steamer headed downstream again he smiled and hummed an American song. The packet now bulged out of the side pocket of his white jacket. For the first time I was aware of something rather sinister in the man.

Here Colonel Strickland was interrupted by a lady at the end of the table.

"But when are we coming to the sapphire?" she asked with a touch of petulance.

"Excuse me! We have already passed it," replied Colonel Strickland. "But have no fear. We shall find it again."

"CAPTAIN CROWTHER," said the colonel, "had contracted what is euphemistically called a Burmese marriage—that is, a marriage without any ceremony at all. He had a child, and he was leaving them planted in this remote little riverside village to get on as best they could, while he bolted back to the United States. We both went ashore at Mandalay, and that was the last I saw of Captain Crowther—until February of last year. Then I met him again."

"In Detroit?" interrupted the man whose theory had provoked the story.

"Not at all," Strickland answered. "On the Irrawaddy. Listen! "

He suddenly leaned forward with his elbows on the table, so that all eyes were fixed on him, and resumed his story:

A MOST holy abbot of the Buddhist religion had died at Shwegu on the upper reaches of the river. His funeral was to be a most ceremonious affair. People would gather for it from all the country round. There would be three days' gaming and play-acting and dancing. The gaming booths were up; the tinsel pagoda in which the body was to be burned, the funeral chariot which was to be dragged to the pagoda in spite of the struggles of the demons to keep it back, the little tinsel temple in which the coffin was to be inclosed, the very ropes up which the temple was to slide to the upper room of the pagoda—all were glittering on the beach of Shwegu waiting for the ceremony; and at every village, along the reaches below, monks and peasants streamed on board my steamer and its lighters.

And at Thabeikkyn who should come aboard, with his head shaved, one shoulder naked, his feet bare, his body wrapped about in the yellow robes of a monk, but Captain Michael D. Crowther! Yes, he was back on the Irrawaddy, but with a beggar bowl for his daily rice, and a mat to stretch out on the deck of the lighter when night came.

He squatted upon the deck apart from the rest of the joy-riders—for a joy ride is what a funeral is in Burma—he opened a great book upon his knees and buried his nose in it, while a few paces away a little boy who waited on him watched him respectfully.

AFTER luncheon I crossed to the lighter and leaned against the rail at his side.

"How do you do, captain?" I asked.

"Colonel, I am glad to see you," he answered immediately. "I recognized you this morning when I came on board. Couldn't keep away, eh?"

"No, nor you either," said I.

And at once he flowed out into confidences: "Yes, colonel. I went right back to Detroit to resume the virile life of an American citizen. But I failed. I had got into the way of going slow. Everybody else was bustling and busy; here was I, sauntering and idle. I got a sense of inferiority, see? Besides, I began to miss this country, the heat of it, the good nature and gayety of it—all these"—and he looked round the lighter with a smile of geniality which struck me suddenly as incongruous in this lean, gaunt man—"all these children. I began to get frightened of Detroit,chimneys. I felt that I was lost in it, like a baby in a forest Besides—besides, you remember Tagaung?"

"Yes."

"You saw me on the beach there?"

"Yes."

"Well, that began to worry me in Detroit. You see, I had done the unforgivable thing from the point of view of an American citizen. I had forgotten the color bar. I had a brown wife and a whity-brown girl child up at Tagaung on the Irrawaddy. Yes, sir, I was grievously distressed about that. I went on worrying and worrying until it suddenly flashed upon me that I wasn't worrying about the color bar at all, but about that brown girl with the rose in her hair and my whity-brown girl child. It had taken me three years to realize that, but, as soon as I did, I came right away back to Burma. I came home. And once I had come home, I wasn't any longer in a hurry. Do you follow me?"

I nodded, and Crowther went on, as he rose and stood at my side against the rail:

"I stayed a day or two at Rangoon. I got off the steamer at Prome and waited for the ferryboat. I put in a week at Mandalay, looking about indolently for a job which I could take on after I had brought Mah Sein and the girl child down from Tagaung. What with my pay and my commissions on the cargoes, I had enough put by to carry on for a time. I looked up old friends, I hung about at the landing places. I made a luxury out of delaying my journey to Tagaung. Everybody I knew knew that I was back in Burma—that's the point, see?"

I was to see very soon, even if I didn't at that moment. Captain Crowther traveled up the river as a passenger. He had worked himself at last into a mood of exaltation over Mah Sein. As he put it to me, night and day he had a sense of her flesh. When he stepped off the gangway plank at Tagaung he was trembling.

An old white-bearded man ambled up to him, and all the men and women bathing and washing their hair in the river lifted their heads to watch.

"I am Moung Lone, the father of Mah Sein, and I have waited for many days for the captain to come."

"In the end I am here," returned Crowther, and his voice shook; for it was in his mind that Mah Sein was dead. But a worse thing had befallen him. Mah Sein had married a Burman and was content.

"I WOULDN'T believe it," Crowther continued, as he told the story on the deck of the lighter—we were approaching Katha in a flame of sunset. "I said that I would go up to the house and see about that myself.

But the old man's face changed, and three or four younger men unostentatiously gathered round us. There was going to be trouble if I persevered. In an upriver village a Burmese girl who has a child by a white man acquires great prestige and is much sought after as a wife. Mah Sein would without doubt be a great personage nowaday at Tagaung. I caught sight of my little girl standing among her playmates—and the sight of her decided me.

"Three years had passed since I had seen her; she was eight years old now, but I hadn't a doubt she was mine. She wore a solar topee, for one thing, quite unnecessarily; also she wore socks and shoes. Pure swagger, you know, as the daughter of a white man. There she was, surrounded by deference, the little queen of the children of Tagaung, having the time of her life, and without a suspicion that her father was within twenty yards of her. Why should I spoil all her fun? If I did get Mah Sein away and take her down to Mandalay, the little girl would be just a half-breed, you see. Here at Tagaung she was It. I turned back and went on board again.

"But I was all broken up. I had failed as a hundred-per-cent American, and now I had failed as an Orientalized European. I went back to Mandalay, and gradually—gradually—I began to think of this."

Captain Crowther plucked then at his saffron robe. "To be nothing at all—not to exist—not even as a soul. To get as near to that ideal on this earth, and finally, after as few reincarnations as possible, to acquire the utter unearthliness which would entitle me at last to extinction."

Captain Crowther's voice died away. His face took a set look, his body fell into a set, motionless pose. I was a hundred miles away from him. I left him squatting on the deck upon his mat, unaware that the steamer was sidling into the busy landing stage at Katha, like any fakir of the East.

But none the less I was conscious that he had not told me everything. I remembered the packet which had bulged in the pocket of his uniform jacket the last time he had edged his steamer out from the beach of Tagaung.

"MICHAEL D. CROWTHER disembarked the next day at Shwegu and disappeared in the throng about the booths," Colonel Strickland continued. "I saw him again a week ago. I saw Captain Michael D. Crowther at luncheon with a party of bright young spirits in the Café Parisien of the Semiramis Hotel."

Michael D. Crowther disappeared

in the throng about the booths.

"In his yellow robe, no doubt," scoffed the youth who had invented a theory in order to tell a story and had then not been allowed to tell it.

He was so well dressed that his clothes were unnoticeable," said Strickland. "On the other hand, he wore his hair en brosse."

The art of the story-teller is suspense, and Colonel Strickland knew it. He leaned back in his chair as though he had more marvels to relate and asked:

"Did any of you know Letty Ransom?

There was a curious movement about the table; a sudden chill was felt. All people who have just died acquire suddenly an enormous interest for the living who knew them, if only casually. And when the one who died is a girl—young, pretty, associated with laughter and daintiness, bright frocks and the dazzle of the footlights, so that the mere mention of her name causes a smile and a then the interest is tremendously increased by a suggestion of something incongruous and bizarre.

"I see you did," said Strickland, with a nod. "Letty Ransom comes into my story. She was described to me as a good little bad girl. At the age of sixteen she ran away from a convent school with a crook. At the end of two years the couple were stranded in London. Letty found an opening in a musical comedy and, as you know, her success was immediate and immense. On the strength of it the crook started an exclusive little gambling hall and Letty brought up the young sheep to be sheared. In addition, she doped and, as you know, died of it the day before yesterday. That was the bad side of her. On the other hand, she stuck to her crook through poverty and every sort of trouble; she had never a bitter word for anybody; she was light-hearted and generous; had a sense of humor. And she was lunching with Michael D. Crowther.... And Marcelle Leslie was of the company."

"Yes," interrupted the lady at the end of the table. "Girls like Letty always have a Marcelle Leslie."

Colonel Strickland looked keenly at the interrupter.

I WENT over to their table [he continued] and shook hands with Letty and Michael D. Crowther. I had never seen a man more unabashed, more unembarrassed. Letty said—you know the attractive way she had of clutching you by the arm, as though you meant a lot to her, when as a fact you meant nothing at all—"You are coming, of course, to the Noughts and Crosses Ball at the Albert Hall, aren't you? Do! Get a scarlet domino and come! "

"The Noughts and Crosses?" I asked. "I never heard of them."

"Why should you?" she rattled on. "You can't hear of brilliant things like that in the jungle. The Noughts are the men and the Crosses are the women. See, as Mr. Crowther says? He's coming."

"Then I think I'll come, too," said I.

"That'll be fine," said Michael D. Crowther.

SO I went. It was the last night of Letty Ransom's life. But she was looking quite lovely. She was dressed as some glorified ultra-exquisite Alsatian peasant girl. As a rule she wore no jewelry, but on this night one glorious big sapphire, blue as the deep waters of the Mediterranean on a day of summer, hung on a platinum chain against her white breast. She danced with me the moment I asked her—she was always kind—and while we danced I did a little secret-service work about Michael D. Crowther. He had been presented to her by some young spark of the Burma Oil Corporation, home on leave, a month ago, and I gathered that he had aroused a friendly feeling in Letty Ransom's little circle.

"He's the loneliest old dear I have ever come across," She said to me. "Whoever of us makes him smile first counts one."

I left the ballroom at half past three, and whom should I see in the atrium of the Albert Hall, obviously waiting for me, but Crowther. He had chosen a yellow domino, and with that wrapped about his gaunt form—if you could only forget his white tie and his starched collar and his stubble of upstanding hair—you might have taken him for the monk he was then and there.

"I'll come along with you, colonel," he said.

I knew enough of the man's ways by now to understand that he was in one of his confessional moods. I called up a taxi.

"Jump in, Captain Crowther," I said, and we drove straight home to my flat, and in a rush he confided.

"When I left Mah Sein behind at Tagaung five years ago, I returned on board the steamer with a little packet," he began.

"I saw it spoiling the fit of your uniform pocket," said I.

"Mah Sein gave it to me to keep for her. There had been some dacoities round about Tagaung and she was afraid. The packet contained her little store of jewelry—her gold amulets and armlets, a chain of amethysts, a jade necklace, a few rings, a Star of Destiny ruby, and one or two spinels set in gold—the whole not worth very much, but of some value all the same. My presents to her. That was what I thought. And since I meant to slip away home to America, it just seemed providential, see? She had given them into my safe-keeping. I remember chuckling to myself as I stood by the wheel and the steamer headed downstream away from Tagaung. I was robbing her. That's the truth. I was stealing from Mah Sein!" He gave a great heave of his shoulders, like a Frenchman.

"I pitched that packet into my trunk," Crowther continued, "and forgot all about it. I didn't come across it again until I was beginning to feel the pull of the Irrawaddy, and fumbled about in my trunk for. the sake of the touch of things which reminded me of the jungle and the white-legged wild buffaloes drinking at the edge of the river, and the rush of the moths to the headlight of the steamer. I wondered what it was for a moment. Then I opened it and saw, glowing at me from the midst of my truck of commonplace presents, a flawless and exquisite sapphire. You, colonel, have seen it, too. You saw it tonight."

I nodded. It was the sapphire which I had seen burning so softly against the white bosom of Letty Ransom. But how in the world did it get there? Michael D. Crowther sat and gazed at the coals of the fire. I dared not break in upon his silence lest once more he should interrupt his confidences at the moment when they most interested me. I had the reward of my reticence.

"I TOOK the packet of jewelry back with me to Tagaung. I offered it to Moung Lone, and he refused it. Mah Sein wanted nothing more of mine. I urged that my presents did not comprise the whole of the packet. There was a sapphire, for instance, and a couple of spinels. Moung Lone was polite but quite firm. Mah Sein remembered quite clearly the sapphire and the spinels, but she had no need of them and was very happy that I should keep them. I felt pretty mean, colonel, I can tell you, when I returned on board. I might have thrown the packet, of course, into the Irrawaddy. But what was the use of that? I laid it aside. Some time, perhaps, a use for it might happen. And a use did happen—afterwards—when I had taken the yellow gown."

"Oh!" I exclaimed. I started forward in my chair. I began dimly to discern the motive for Crowther's tremendous pilgrimage from Thabeikkyn to the Albert Hall.

"By the side of my monastery," he resumed, "there is a pagoda, tapering up smooth and slender two hundred and forty feet to its Ti, and a lady who is wealthy was installing the electric light, so that a scaffolding was up."

COLONEL STRICKLAND broke off his narrative here to explain two of the customs of the rich natives. They equipped their pagodas thus, even in remote places, so that at night rings and long descending lines of golden fire might shine far across the country in the darkness. Besides, ladies of great virtue would give their jewelry to be strung in chaplets high up the pagoda under the Ti, the actual top with the tinkling pieces of metal which has the look of a closed umbrella.

Crowther had imitated those virtuous ladies [Strickland resumed]. He had strung the anklets and the chains and the bracelets and the sapphire into a chain, and, while the scaffolding was still erected, he had fixed the chain at the very summit of the pagoda as a votive offering. There it remained.

"But one day," said Crowther, "there came two new monks to the pagoda. You know, colonel, the kind of monks I mean."

"Released convicts," said I.

"Yes," agreed Michael D. Crowther. There are only two classes of people who have their heads shaved in Burma—monks and convicts. Monks take no vows; they have no ceremonies of initiation; they require no training or knowledge. They shave their heads, procure a yellow robe and a begging bowl, and the thing's done. You see the advantage for a convict on release. He is no longer known as a convict by his shaven head. He is a ponghi. And when, after a time, he walks out of the monastery and discards his robe, he is a man who has ceased to be a ponghi—that's all. Thus these two scoundrels sought refuge at Thabeikkyn, and one night, while the monastery slept, they, with nothing to help them but a single long bamboo pole with a hook at the end of it, scaled the pagoda and robbed it of Mah Sein's sapphire. This theft flung him across the world.

"It was my symbol of expiation, see!" he said. "It had just got to hang again in its place under the Ti of the Thabeikkyn pagoda, even if I dived to the bottom of the sea to find it. We, as you know, colonel, are not without some sort of organization. I followed the two thieves to Rangoon. There they had separated and the one with the sapphire had taken ship to Ceylon. I followed him. He had gone up to Kandy. I followed him there. He had sold the stone to one of the dealers under the colonnade at the side of the hotel. When I found the dealer, he in his turn had sold it. He had sold it to Harry Upway."

"THE lover of Letty Ransom!" I exclaimed.

"Yes," said Crowther. "I still had some money left. I came to England. I meant to buy that sapphire from him, but he had given it to Letty. I made her acquaintance, became one of her friends, and asked her to sell it to me. She refused. But tomorrow afternoon I am going to tell her the whole story—and I think she will give it to me."

"I, too, think she will," said I.

It was now six o'clock in the morning. Letty Ransom was on her way back with her party of friends to her flat in the Semiramis Hotel. You remember what happened. They had breakfast together and left Letty. She went to bed, took an overdose of cocaine, and never woke again.

The lady at the head of the table heaved a sigh of discontent.

"Then, after all, the poor man never got his sapphire back," she said.

"Wait! " Colonel Strickland advised.

CROWTHER had made his plans shrewdly [the colonel continued]. Marcelle Leslie was, of course, the enemy. She would certainly not allow Letty to hand this lovely stone back. If it was to be given to anybody, it must assuredly be given to her. Marcelle Leslie had therefore to be got out of the way during that afternoon. Crowther invited her to lunch with him in the café of the Semiramis, and arranged that his young friend of the B.O.C. should come in after luncheon and take her to a matinée.

Crowther would thus be certain of sufficient time in which to develop his plan. And everything worked to the time-table.

At one-fifteen Michael D. Crowther was waiting in the lounge. At one-thirty Marcelle arrived, all black eyes and scarlet lips and flashing teeth, not a whit the worse for her night at the Noughts and Crosses Ball. They went into the café and took the table which he had ordered.

"What will you have?" asked Crowther, handing to her the bill of fare.

"Oh, anything, of course," said Marcelle Leslie, and she proceeded to order just what she liked, indifferent to seasons and prices.

"And get me a cocktail, old dear, with a dash of absinthe. I left my platinum bag in Letty's flat this morning and I am just going to run upstairs and get it."

"But her door will be locked and you'll wake her up," Crowther objected.

"No," said Marcelle Leslie. "We left her door with the catch fastened back this morning. She asked us to. She didn't want to be bothered by having to get out of bed and open it."

By a chance which Marcelle must have considered providential, the lift was on its way between the floors. Marcelle, who never could wait a second for anything without losing her temper, ran up to the third floor on which Letty's flat was placed, and after five or ten minutes walked down again.

She rejoined Crowther with her platinum bag in her hand and drank her cocktail in one gulp. She burst into spasmodic conversation—what a splendid ball it was, and how well dear old Carrie Baines looked, except that she daren't laugh lest the enamel should crack, and what a pity Sir James Pollant didn't give that sort of thing up! He had been all right until he got into the sixties. "'Old dot and carry one,' I call him," she said, and suddenly her effervescence vanished. A haggard face peered into Crowther's, a trembling hand clutched his sleeve.

"DON'T mention to a soul that I went upstairs after my bag. Promise me, old thing! It might do me a lot of harm. I'm started now, you know. I'm opening in a really fine singing part at the Melody Theater in a fortnight. I've got to be careful."

She was off again in her hard, swift, self-concentrated rattle before Michael D. Crowther, who was nowadays rather slow on the intake, could answer her. She kept it up until the young spark from the Burma Oil Corporation came to fetch her for the matinee.

"I have had a divine lunch," she said, "and you'll remember your promise, won't you?"

"Was Letty getting up?" Crowther asked.

"When?" asked Marcelle Leslie,with an angry frown. "The last time I saw her, she was going to bed."

MICHAEL D. CROWTHER was a little at a loss. The one solid fact he clung to was that Letty Ransom couldn't get up in under an hour and a half. It was now half past two. Accordingly he hung about the Semiramis until four. He would still have an hour, he reckoned, before Marcelle could return.

He went upstairs at four, and the doorway of Letty's flat was barred by a policeman, the manager, and the doctor attached to the hotel.

"You can't come in," they said in one voice. A fourth voice, however, was added to the chorus. A second doctor, a friend of Letty, came out from the bedroom.

"Mr. Crowther was one of Letty's friends," he said. "He may know something."

Crowther was admitted into the lobby. "What's the matter?" he asked.

"Letty's dead," said the doctor, and he led Crowther into the bedroom where she lay, her little lively troubled soul at rest.

You must remember, of course, Crowther's point of view. His heart was set on the recovery of the sapphire. It came first and last in his thoughts. He consequently kept his head and looked about the room. There were Letty's rings on a china tray, Letty's gown and stockings thrown about the room; Letty's shoes kicked under a chair. Where, then, was Letty's sapphire?

"When did she die?" he asked.

"Half an hour ago—all alone here. Certainly not more than half an hour ago," replied her friend the doctor miserably.

"Could she have been saved?" asked Crowther.

The doctor took his time in answering.

"I think so. An hour ago—perhaps. Two hours ago—yes."

"You are sure of that?"

"Yes." The doctor looked at his little friend. "It was that ball, you see. In the ordinary way, Letty's friends would have been ringing her up all the time after eleven in the morning, proposing this and arranging that. But they were all in bed, too. It was just by chance that I called her on the telephone half an hour ago and could get no answer."

CROWTHER left his address with the policeman and, descending to the ground floor, called up a taxi. He was driven to Marcelle's lodging. She had not returned from her matinée. Crowther sat down and waited. She came in with a swirl at half past five, and she turned white and she staggered as she saw Crowther seated in her chair.

"I gave you no promise, Marcelle, at luncheon."

Marcelle Leslie drew in her breath in a horrible sort of whistle.

"What do you mean?" she asked.

"Letty's dead," said Crowther, "and you could have saved her life."

Marcelle collapsed into a chair. She was shaking like a man in a fever.

"I was frightened when I saw her," she stammered, her teeth clicking against each other. "She was breathing in a dreadful, noisy way. I had to think of myself, hadn't I? She took cocaine. Supposing that she was dying of it! There would be a scandal. All who had been with her—who were her friends—would be tarred with it... I snatched up my bag and ran away."

"And so Letty died, whereas she might have recovered," said Crowther.

Marcelle Leslie was suddenly on her knees at his side. "You won't say that? You won't give me away? No one saw me go into her room. Please... promise! "

Marcelle Leslie was suddenly on her knees at his side... "You

won't give me away? No one saw me go into her room. Please...

The tears were rolling down her cheeks.

"I'll promise to keep silent on one condition," said Crowther. "You must give me back the sapphire you stole from Letty's dressing table."

MARCELLE sprang up from her knees, smiling, relieved of all her fears. The sapphire? What did that matter? She was dealing, after all, with someone like herself—a blackmailer who could be bought off—and cheaply, too.

"Here you are, old dear," she cried, and, tumbling the contents out of her platinum bag, she pushed the sapphire pendant across the table to him.

"After all, you're just like me," she said with a laugh of comradeship.

"I am very likely worse," said Crowther....

All that happened two days ago. This afternoon I saw Michael D. Crowther off from Southampton on the first stage of his journey back to Thabeikkyn.

I promised you a story which would cover the surface of the world and yet be as complete as any fable of old times.

WHEN Colonel Strickland had finished, there was a moment's silence, and then the chairs were pushed back amid a murmur of thanks to him.

"Yet," added Strickland, "have I told you the absolute end? I don't know. If not, here it is. Crowther, at all events, would agree with me.

"The lease of my flat is up and I am moving into the Semiramis. On coming back from Southampton, I went to see my new flat. It is the one which Letty Ransom occupied.

"Everything of hers had been removed. Only a thrush had flown in at the window and was singing as if there it had its home."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.